A Game of Roads: the North Omaha Freeway and Historic Near North Side

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

2006 Restore Omaha Program

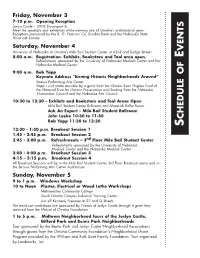

Friday, November 3 7-10 p.m. Opening Reception Joslyn Castle – 3902 Davenport St. Meet the speakers and exhibitors while viewing one of Omaha’s architectural gems. Reception sponsored by the B. G. Peterson Co, Dundee Bank and the Nebraska State Historical Society Saturday, November 4 VENTS University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Milo Bail Student Center at 62nd and Dodge Streets 8:00 a.m. Registration. Exhibits, Bookstore and Tool area open. E Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 9:00 a.m. Bob Yapp Keynote Address “Turning Historic Neighborhoods Around” Strauss Performing Arts Center Yapp’s visit made possible by a grant from the Charles Evan Hughes Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and funding from the Nebraska Humanities Council and the Nebraska Arts Council. 10:30 to 12:30 – Exhibits and Bookstore and Tool Areas Open Milo Bail Student Center Ballroom and Maverick Buffet Room Ask An Expert – Milo Bail Student Ballroom John Leeke 10:30 to 11:30 CHEDULE OF Bob Yapp 11:30 to 12:30 S 12:30 - 1:30 p.m. Breakout Session 1 1:45 - 2:45 p.m. Breakout Session 2 2:45 - 3:00 p.m. Refreshments – 3rd Floor Milo Bail Student Center Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 3:00 - 4:00 p.m. Breakout Session 3 4:15 – 5:15 p.m. Breakout Session 4 All Breakout Sessions will be in the Milo Bail Student Center 3rd Floor Breakout rooms and in the Strauss Performing Arts Center Auditorium Sunday, November 5 9 to 1 p.m. -

2016 Participating Organizations

PRESENTS 2016 PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS “Living H2O” Lutheran Campus Ministry American Red Cross 100 Black Men of Omaha Analog Arts - Omaha Under the Radar 402 Arts Collective Angels Among Us 75 North Anti-Defamation League 95.7 The BOSS Antwaun Rollerson Foundation A Light In A Dark Place Arthritis Foundation A Time to Heal Artists’ Cooperative Gallery Abide Arts For All, Inc. Acappella Omaha Chorus of Sweet Adelines Assembly of the Saints Church International Assistance League of Omaha ACLU of Nebraska Assure Women’s Center Advocates for the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer At Ease USA Center Audubon Society of Omaha aetherplough Autism Action Partnership African American Empowerment Network Autism Center of Nebraska, Inc. African Culture Connection Autism Society of Nebraska AIM Avenue Scholars Foundation Aksarben Curling Association Avoca Public Library AKSARBEN Foundation B and B Boxing Academy All Care Health Center B’nai Israel Synagogue All Saints Catholic School Ballet Nebraska AllPlay Miracle Baseball League Banister’s Leadership Academy Ally Mentoring Barrientos Scholarship Foundation ALS Association Mid-America Chapter Basset and Beagle Rescue of the Heartland ALS in the Heartland Beginning Experience of Omaha Alzheimer’s Association Bellevue Economic Enhancement Foundation American Cancer Society Bellevue Housing Authority American Diabetes Association Bellevue Jr. Sports (BJSA) American Heart Association Bellevue Library Foundation American Italian Heritage Society Bellevue Little Theatre American Lung Association in Nebraska Bellevue Public Schools Foundation American Muslim Institute Bellevue Royal Family Kids Camp American Parkinson Disease Association Nebraska Bellevue University Chapter OmahaGives24.org Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts Cathedral Arts Project Bennington Public Schools Foundation Catholic Charities Benson Area Refugee Task Force Catholic Charities Phoenix House Benson First Friday Catnip and Tails Rescue, Inc. -

Omaha, Nebraska, Experienced Urban Uprisings the Safeway and Skaggs in 1966, 1968, and 1969

Nebraska National Guardsmen confront protestors at 24th and Maple Streets in Omaha, July 5, 1966. NSHS RG2467-23 82 • NEBRASKA history THEN THE BURNINGS BEGAN Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence BY ASHLEY M. HOWARD S UMMER 2017 • 83 “ The Negro in the Midwest feels injustice and discrimination no 1 less painfully because he is a thousand miles from Harlem.” DAVID L. LAWRENCE Introduction National in scope, the commission’s findings n August 2014 many Americans were alarmed offered a groundbreaking mea culpa—albeit one by scenes of fire and destruction following the that reiterated what many black citizens already Ideath of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. knew: despite progressive federal initiatives and Despite the prevalence of violence in American local agitation, long-standing injustices remained history, the protest in this Midwestern suburb numerous and present in every black community. took many by surprise. Several factors had rocked In the aftermath of the Ferguson uprisings, news Americans into a naïve slumber, including the outlets, researchers, and the Justice Department election of the country’s first black president, a arrived at a similar conclusion: Our nation has seemingly genial “don’t-rock-the-boat” Midwestern continued to move towards “two societies, one attitude, and a deep belief that racism was long black, one white—separate and unequal.”3 over. The Ferguson uprising shook many citizens, To understand the complexity of urban white and black, wide awake. uprisings, both then and now, careful attention Nearly fifty years prior, while the streets of must be paid to local incidents and their root Detroit’s black enclave still glowed red from five causes. -

An Equation for Success: $10 Million Gift, Plus

AN EQUATION FOR SUCCESS: $10 MILLION GIFT, PLUS OUTSTANDING SCIENCE PROGRAMS, EQUALS INFINITE POSSIBILITIES P30 FALL 2017 FALL Volume 33 Issue 3 33 Issue Volume Message from the President A Time of Community and Thanksgiving n this annual season of thanksgiving, I am indeed grateful for our supportive alumni and friends, dedicated faculty and staff, and exceptionally talented students. Our University continues to attract record numbers of students, receive national recognition for academic excellence, and engender tremendous support from our alumni and donors. In September, we announced a transformational $10 million gift from longtime Creighton friends and supporters George Haddix, PhD, MA’66, and his wife, Susan, to build and Ienhance academic programming in the College of Arts and Sciences. I am thankful for George and Susan’s generous commitment to Creighton, and excited about the many opportunities it will offer our students and faculty. I am also grateful for our spirit of community on campus, which lifts us up in hopefulness and comforts us in times of tragedy. At the beginning of the academic year, we gathered in prayer and support after a four-vehicle crash claimed the life of one of our bright, young students, and injured three others. An alumna traveling in a separate car also was injured. Joan Ocampo-Yambing, the 19-year-old computer science major from Rosemount, Follow me: Minnesota, who died in the collision, was remembered on campus as a bright light, a @CreightonPres loving friend, and an outstanding student. She is greatly missed. CreightonPresident We also mourned the passing of several faculty and staff, along with two former members of our Board of Trustees. -

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885 (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Ray H. Mattison, “The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885,” Nebraska History 35 (1954): 17-43 Article Summary: Frontier garrisons played a significant role in the development of the West even though their military effectiveness has been questioned. The author describes daily life on the posts, which provided protection to the emigrants heading west and kept the roads open. Note: A list of military posts in the Northern Plains follows the article. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: map of Army posts in the Northern Plains states, 1860-1895; Fort Laramie c. 1884; Fort Totten, Dakota Territory, c. 1867 THE ARMY POST ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS, 1865-1885 BY RAY H. MATTISON HE opening of the Oregon Trail, together with the dis covery of gold in California and the cession of the TMexican Territory to the United States in 1848, re sulted in a great migration to the trans-Mississippi West. As a result, a new line of military posts was needed to guard the emigrant and supply trains as well as to furnish protection for the Overland Mail and the new settlements.1 The wiping out of Lt. -

Miscellaneous Collections

Miscellaneous Collections Abbott Dr Property Ownership from OWH morgue files, 1957 Afro-American calendar, 1972 Agricultural Society note pad Agriculture: A Masterly Review of the Wealth, Resources and Possibilities of Nebraska, 1883 Ak-Sar-Ben Banquet Honoring President Theodore Roosevelt, menu and seating chart, 1903 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation invitations, 1920-1935 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation Supper invitations, 1985-89 Ak-Sar-Ben Exposition Company President's report, 1929 Ak-Sar-Ben Festival of Alhambra invitation, 1898 Ak-Sar-Ben Horse Racing, promotional material, 1987 Ak-Sar-Ben King and Queen Photo Christmas cards, Ak-Sar-Ben Members Show tickets, 1951 Ak-Sar-Ben Membership cards, 1920-52 Ak-Sar-Ben memo pad, 1962 Ak-Sar-Ben Parking stickers, 1960-1964 Ak-Sar-Ben Racing tickets Ak-Sar-Ben Show posters Al Green's Skyroom menu Alamito Dairy order slips All City Elementary Instrumental Music Concert invitation American Balloon Corps Veterans 43rd Reunion & Homecoming menu, 1974 American Biscuit & Manufacturing Co advertising card American Gramaphone catalogs, 1987-92 American Loan Plan advertising card American News of Books: A Monthly Estimate for Demand of Forthcoming Books, 1948 American Red Cross Citations, 1968-1969 American Red Cross poster, "We Have Helped Have You", 1910 American West: Nebraska (in German), 1874 America's Greatest Hour?, ca. 1944 An Excellent Thanksgiving Proclamation menu, 1899 Angelo's menu Antiquarium Galleries Exhibit Announcements, 1988 Appleby, Agnes & Herman 50 Wedding Anniversary Souvenir pamphlet, 1978 Archbishop -

Directions to Cleveland Operations

Directions to Cleveland Works 1600 Harvard Avenue Cleveland, OH 44105 Please note that there are no sleeping areas at this facility. You must stop at a rest area or truck stop. From Interstate 71 th North bound: Take 1-71 North to Exit 247A, W. 14 St. and Clark Ave. Make a right at the end of the exit ramp. nd Then take route 176 south, approx. ¼ mile on your left. Harvard Ave. will be your 2 exit. At the end of the rd ramp take a left. Gate 6 will be at the 3 traffic light on your right. ¾ Closest Rest Area Exit 209, Lodi From Interstate 77 North bound: Take 1-77 North to exit 159A (Harvard Ave). At the end of the ramp take a left. Gate 6 will be about 1 mile on your left. ¾ Closest Rest Area Exit 111, North Canton From Interstate 80 East East or West bound: Exit 11 / 173 to I-77 North. Take I-77 North to exit 159A (Harvard Ave). At the end of the ramp take a left. Gate 6 will be about 1 mile on your left. ¾ Closest Rest Area East Bound between exits 10 / 161 and 11 / 173 West Bound between exits 14 / 209 and 13A / 193 From Interstate 480 East bound: Exit 17 onto Route 176 North. Exit onto Harvard Ave. Take a right onto Harvard Ave. Gate 6 will rd be at the 3 traffic light on your right. ¾ Closest Rest Area None West bound: Exit 20B onto I-77 North. Take 1-77 North to exit 159A (Harvard Ave). -

City of Cleveland Location in the NOACA Region

CITY OF C LEVEL AND T HE C ITY OF C LEVELAND R OADWAY P AVEMENT M AINTENANCE R EPORT T ABLE OF C ONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Background ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. PART I: 2016 Pavement Condition ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 4. PART II: 2018 Current Backlog ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 34 5. PART III: Maintenance & Rehabilitation (M&R) Program .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Nebraska's 2019-20 Approved Title I Schoolwide Programs

NEBRASKA'S 2019-20 APPROVED TITLE I SCHOOLWIDE PROGRAMS Building Reviewed District id Agency id District Name Agency Name Grade of Span Plan Plan Last Peer ESU CONSORTIA ESU SW PeerSW Review Yr. NDE TitleNDE I Consultant ESSA Monitoring Year Monitoring ESSA CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-003 ALCOTT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-004 HAWTHORNE ELEMENTARY K-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-005 LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL K-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-006 LONGFELLOW ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-008 WATSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0123-000 SILVER LAKE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 09 01-0123-002 SILVER LAKE ELEMENTARY at BLADEN K-6 4/2018 3 1 TIM 02-0009-000 NELIGH-OAKDALE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 02-0009-004 WESTWARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-2 4/2018 3 1 TIM 02-0009-000 NELIGH-OAKDALE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 02-0009-005 EASTWARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3-6 4/2018 3 1 TIM 02-2001-000 NEBRASKA UNIFIED DISTRICT 1 02-2001-002 CLEARWATER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-6 4/2019 1 2 TIM 02-2001-000 NEBRASKA UNIFIED DISTRICT 1 02-2001-004 ORCHARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-6 4/2019 1 2 TIM 02-2001-000 NEBRASKA UNIFIED DISTRICT 1 02-2001-006 VERDIGRE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-6 4/2019 1 2 TIM 04-0001-000 BANNER COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 04-0001-002 BANNER COUNTY ELEMENTARY K-6 4/2019 1 2 CATHY 05-0071-000 SANDHILLS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 10 05-0071-002 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AT HALSEY K-6 4/2017 2 3 PAT 06-0001-000 BOONE CENTRAL -

On the Front Lines for Racial Equality

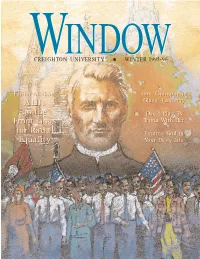

WWCREIGHTONINDOWINDOW UNIVERSITY ■ WINTER 1995-96 FatherFather Markoe:Markoe: Our ‘Champagne A Life Glass’ Economy on the Don’t Play TV Front Lines Trivia With Her for Racial Finding God in Equality Your Daily Life LETTERS WINDOW Magazine edits Letters to the INDOW Editor, primarily to conform to space W■ ■ limitations. Personally signed letters Volume 12/Number 2 Creighton University Winter 1995-96 are given preference for publication. Our FAX number is: (402) 280-2549. E-Mail to: [email protected] Fr. Markoe’s Battle Against Racism ‘And If the Rules Change?’ Bob Reilly tells you about a man who I have read with interest the article “The was a lifelong fighter. Fr. Markoe Social Roots of Our Environmental found a cause for his fighting ener- Predicament” by Dr. Harper in your Fall gy. The word portrait of a strong- 1995 issue of WINDOW. minded Jesuit begins on Page 3. I would like to pose a question for Dr. Harper. In this third human environmental The Rich Get Richer, revolution, supposing we were to discov- er an inexhaustible source of energy. I The Poor Get Poorer am assuming that the laws of supply and Gerard Stockhausen, S.J., talks about what he calls “our cham- demand would eventually lead it to be at pagne-glass economy.” In this case, it doesn’t mean champagne an inconsequential cost. for everyone; it means the shape of our economy that puts the What would that do to the human liv- rich at the broad top of the glass and the poor at the narrow ing conditions in the world? bottom. -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 233/Monday, December 4, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 233 / Monday, December 4, 2000 / Notices 75771 2 departures. No more than one slot DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In notice document 00±29918 exemption time may be selected in any appearing in the issue of Wednesday, hour. In this round each carrier may Federal Aviation Administration November 22, 2000, under select one slot exemption time in each SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION, in the first RTCA Future Flight Data Collection hour without regard to whether a slot is column, in the fifteenth line, the date Committee available in that hour. the FAA will approve or disapprove the application, in whole or part, no later d. In the second and third rounds, Pursuant to section 10(a)(2) of the than should read ``March 15, 2001''. only carriers providing service to small Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. hub and nonhub airports may L. 92±463, 5 U.S.C., Appendix 2), notice FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: participate. Each carrier may select up is hereby given for the Future Flight Patrick Vaught, Program Manager, FAA/ to 2 slot exemption times, one arrival Data Collection Committee meeting to Airports District Office, 100 West Cross and one departure in each round. No be held January 11, 2000, starting at 9 Street, Suite B, Jackson, MS 39208± carrier may select more than 4 a.m. This meeting will be held at RTCA, 2307, 601±664±9885. exemption slot times in rounds 2 and 3. 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW., Suite Issued in Jackson, Mississippi on 1020, Washington, DC, 20036. November 24, 2000. e. Beginning with the fourth round, The agenda will include: (1) Welcome all eligible carriers may participate.