Education Funders Research Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Basics Achieving a Liberal Education for All Children

Beyond the Basics Achieving a Liberal Education for All Children Edited, and with an introduction and conclusion by Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Diane Ravitch Beyond the Basics Achieving a Liberal Education for All Children Beyond the Basics Achieving a Liberal Education for All Children Edited, and with an introduction and conclusion, by Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Diane Ravitch Published July 2007 by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is a nonprofit organization that conducts research, issues publications, and directs action projects in elementary/secondary education reform at the national level and in Ohio, with special emphasis on our hometown of Dayton. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. Further information can be found at www.edexcellence.net/institute or by writing to the Institute at: 1701 K Street, NW Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20006 This publication is available in full on the Institute’s web site; additional copies can be ordered at www.edexcellence.net/institute/publication/order.cfm. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • Why Liberal Learning. 1 Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Diane Ravitch PART I LIBERAL LEARNING: ITS VALUE AND FUTURE • Pleasure, Beauty, and Wonder: The Role of the Arts in Liberal Education. 11 Dana Gioia • What Do They Know of Reading Who Only Reading Know?: Bringing Liberal Arts into the Wasteland of the “Literacy Block” . 17 E.D. Hirsch, Jr. • W(h)ither Liberal Education?: A Modest Defense of Humanistic Schooling in the Twenty-first Century. 25 David J. Ferrero PART II RESTORING LIBERAL ARTS TO THE K-12 CURRICULUM • Testing, Learning, and Teaching: The Effects of Test-based Accountability on Student Achievement and Instructional Time in Core Academic Subjects. -

Spending by NYC on Charter School Facilities: Diverted Resources, Inequities and Anomalies

Spending by NYC on Charter School Facilities: Diverted Resources, Inequities and Anomalies A report by Class Size Matters October 2019 Spending by NYC on Charter School Facilities: Diverted Resources, Inequities and Anomalies Acknowledgements This report was written by Patrick Nevada, Leonie Haimson and Emily Carrazana. It benefitted from the assistance of Kaitlyn O’Hagan, former Legislative Financial Analyst for the NYC Council, and Sarita Subramanian, Supervising Analyst of the NYC Independent Budget Office. Class Size Matters is a non-profit organization that advocates for smaller classes in NYC public schools and the nation as a whole. We provide information on the benefits of class size reduction to parents, teachers, elected officials and concerned citizens, provide briefings to community groups and parent organizations, and monitor and propose policies to stem class size increases and school overcrowding. A publication of Class Size Matters 2019 Design by Patrick Nevada 2 Class Size Matters Spending by NYC on Charter School Facilities: Diverted Resources, Inequities and Anomalies Table of Contents Table of Figures 4 Cost of Facility Upgrades by Charter Schools and Missing DOE Matching Funds 9 Missing Matching Funds 11 Spending on Facility Upgrades by CMO and DOE Matching Funds 16 DOE spending on leases for Charter schools 17 Cost of buildings that DOE directly leases for charter schools 21 DOE-Held Lease Spending vs Lease Subsidies 23 DOE Lease Assistance for charters in buildings owned by their CMO or other related organization 26 Cost of DOE Expenditures for Lease Assistance and Matching Funds for each CMO 31 Proposed legislation dealing with the city’s obligation to provide charter schools with space 33 Conclusion and Policy Proposals 34 Appendix A. -

Robert Hughes

186 Wyrick Book Reviews 187 GoJomschtok,. L and Glezar. A. (19'77). ~ fIrl in o:ik. New York: Random House. BOOK REVIEWS Kruger, B. (198n. Remote control. In B. Wallis (Ed.), Blasttd Q&gories: An: tmthology of writings by C01Itt:rrrpm'l'ry "rtists, PI'- 395-4(6. New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art. Kruger, B. (1988). Remote control. ArlfrmIm. 24 (5). 11-12- Kruger, B. (1989). Remote control. A:rtfurum. 17 (8), 9-11. Terry Barrett (1994) Criticizing Art: Lanier, V. (1969). The teadting of art as social revolution. Phi Del", KRpptm, 50 (6), 314-319. Understanding the Contemporary Unker, K. (1985). Disinfonnation. Artj'onIm, 2J (10), 1ffi-106. Mountain View: Mayfield Publication Company. McGee, M. (l982). ArtisIS making the news: Artists remaking the 200 pages. ISBN 1-55934-147-5 (paper) $14.95 news. Aftmm.ge, 10 (4), 6-7. McQuail, O. (1987). MIas llImmwnialtion tJwry: An: introdwction. London: Sage. Nadaner, D. (1985). Responding to the image world. Art E4wation, 38 (1), 9-12. Paoletti. J. T. (1985). At the edge where art heromes media and John H . White Jr. message becomes polemiC. A~, 59 (9), 133. Rodriguez.. G. (1984). Disirif!mrWit:m: The m1mwfactwreof CtlrIStl'It. [Exhibition catalogueJ. New York: The Alternative Museum. RosIer, M. (Producer). (t988). Bam ro brsol4: MfIrllIII. RosftT rtwl.s !he stnUlgt CllStof ba:by M [VkieotapeJ. New York: Pape!" Tiger Terry Barrett' s newest contribution to ttitka) practice, Television. Criticizing Art: Understllnding the Contemponry, Mountainview, Tamblyn, C. (198'7). Video Art AIt Historical Sketch. High CA: Mayfield Publishing Co. 1994, provides the fields of art Per{orrtwIu37, 10 0 ), 33-37. -

January/February 2017 | Volume 3, Issue No

QUEENS LIBRARY MAGAZINE January/February 2017 | Volume 3, Issue No. 1 Food industry entrepreneurs will love Jamaica FEASTS p.4 Queens Library can help with your New Year’s resolutions p.6 Roxanne Shanté Here’s what you missed at Festival an Koulè p.9 Headlines Broken What’s on this African- American History Month p.11 Heart Week p.15 QueensLibrary.org 1 QUEENS LIBRARY MAGAZINE A Message from the President and CEO Dear Friends, At Queens Library, we are continually working to understand how best to serve the dynamic needs of its diverse communities. To ensure that the Library can be as meaningful and effective as possible in these increasingly complex times, we have embarked on a strategic planning process that will guide the Library for the next five years. The success of this process depends on your engagement. We are seeking the input of a broad range of stakeholders and ultimately determining how the Library defines its mission and vision, sets its priorities, uses its resources, and secures its position as one of the most vital institutions in the City of New York. As part of this ambitious and highly inclusive planning process, we are conducting a series of discussions with everyone who uses, could use, serves, oversees, funds, and appreciates Queens Library about its strengths and weaknesses as well as the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. One of the most critical conversations we want to have is with you. To get the Sincerely, dialogue started, please visit our website, www.queenslibrary.org, to take a survey about your experiences with the Library and your thoughts about its future. -

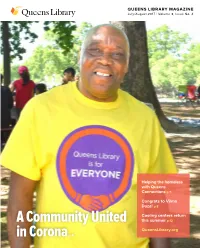

July/August 2017 | Volume 3, Issue No

QUEENS LIBRARY MAGAZINE July/August 2017 | Volume 3, Issue No. 4 Helping the homeless with Queens Connections p.7 Congrats to Vilma Daza! p.8 Cooling centers return A Community United this summer p.12 QueensLibrary.org in Corona p.4 1 QUEENS LIBRARY MAGAZINE A Message from the President and CEO Dear Friends, On Tuesday, June 6, the New York City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio approved the City’s budget for Fiscal Year 2018. This budget includes an additional $30 million in capital funding for critical maintenance and repairs for Queens Library, and marks the third consecutive funding increase for the City’s three library systems. Queens Library also received a total of $10.78 million from individual City Council members who represent Queens, and a $1.4 million baselined annual increase to operate the new Hunters Point Community Library. When we are able to improve our buildings, more New Yorkers visit, check out materials, attend programs and classes, access opportunity, and strengthen themselves and their communities. Thank you to Mayor de Blasio, Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, Finance Chair Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, Majority Leader Jimmy Van Bramer, Library Sub-Committee Chair Andy King, and the members of the New York City Sincerely, Council for once again investing in our City’s libraries. I’d also like to thank our partners in DC 37 and Local 1321 for their leadership and support through the budget negotiating process. Dennis M. Walcott Finally, I send my thanks and appreciation to our staff, to the Friends of the President and CEO Library, and to our tireless library advocates, who attended rallies, wrote letters, sent tweets, and posted virtual sticky notes online, all to make one message clear: that an investment in libraries is an investment in all New Yorkers. -

BROWN-DISSERTATION.Pdf (1.515Mb)

Copyright by Amy E. Brown 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Amy Elizabeth Brown Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Strings Attached: Performance and Privatization in an Urban Public School Committee: Douglas E. Foley, Supervisor Edmund T. Gordon João Costa Vargas Keffrelyn Brown Nadine Bryce Strings Attached: Performance and Privatization in an Urban Public School by Amy Elizabeth Brown, B.A., M.S.T. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To the Brooklyn public school students, parents and teachers who showed me how to be curious enough to pursue difficult questions, and brave enough to engage the answers. Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without ongoing support from family members, friends, and teachers, in and outside of LSA. I thank my immediate family, David, Laura and Sarah Brown, as well as my Bubby, Sarah Shumofsky for consistently lending spiritual and physical nourishment, support and encouragement through this journey. Thanks to Frank Alagna and John Meehan for providing me with an incredible Rhinebeck writer’s retreat, where I gained motivation and mental space to see this project through. Although I use pseudonyms for LSA staff, students and families and cannot name them here, they were an invaluable source of friendship and support. I thank my “chosen” family -

Crain's New York Business1 November 13, 2017

I SNAPS Celebrity chefs take aim at food waste r--------, More than 50 of the city's top chefs and mixologists provided food and drinks for the 800-plus revelers at a speakeasy-themed benefit for City Harvest. The dinner raised a record $1.5 million, in part because of its auction of one-of-a-kind experiences. One donor paid $50,000 to go on a bar crawl with chef/restaurateurs Scott Conant of Fusco, Marc Murphy of Landmarc and Geoffrey Zakarian of The Lambs Club. Geoffrey Zakarian, chairman of City Harvest's Food Council and the event's host, and Alfred Portale, executive chef and partner of Gotham Bar and Grill, during the festivities at the Metropolitan Pavilion. Eric Ripert, chef and co-owner of Le Bernardin and vice chairman of City Harvest's board, with his wife, Sandra, at .the Oct. 19 event. The dinner and si lent and live auctions raised enough money to rescue 6 million pounds of food. Beyond books Honoring a legend LSA Family Health Service, which was founded by Little Sisters of the Assumption to provide various types of aid to those struggling in Harlem and the Bronx, held a benefit Oct. 16. Broadway actress Doreen Montalvo performed a tribute to event honoree Chita Rivera, a stage and screen legend who The Queens Library took in a record $528,000 to provide such services as English received the Presidential classes and job training at its Oct. 17 fundraiser. Jeffrey Barker, president of Bank Medal of Freedom in 2009. of America for New York state; honoree Lester Young Jr., regent at large of the University of the State of New York; Dennis Walcott, president and chief execu tive ofthe Queens Library; honoree Patricia Harris, chief executive of Bloomberg Philanthropies; and Judith Bergtraum, vice chancellor for facilities planning, construction and management for the City University of New York, attended. -

Tribune-Epaper-122916-Opt.Pdf

Vol. 46, No. 52, Dec. 29, 2016 - Jan. 4, 2017 • queenstribune.com Person2016 YearOf The Queens Library President And CEO Dennis Walcott: The Next Chapter Of The Queens Library Photo by Bruce Adler by Photo Page 2 Tribune Dec. 29, 2016 - Jan. 4, 2017 • www.queenstribune.com LEGAL NOTICE LEGAL NOTICE LEGAL NOTICE LEGAL NOTICE LEGAL NOTICE LEGAL NOTICE SKYWEN LLC. Art. of Org. Office located in Queens Art. Of Org. filed with the copy of your Answer or, if based upon the County in COURT. Dated: Bay Shore, filed with the SSNY on County. SSNY has been des- Sect’y of State of NY (SSNY) the Complaint is not served which the mortgaged prem- New York January 29, 2015 09/16/16. Office: Queens ignated for service of process. on 02/03/16. Office in with this Summons, to serve ises is situated. HSBC Bank FRENKEL, LAMBERT, WEISS, County. SSNY designated as SSNY shall mail copy of any Queens County. SSNY has a Notice of Appearance on USA, National Association, WEISMAN & GORDON, LLP agent of the LLC upon whom process served against the been designated as agent the attorneys for the plaintiff as Trustee, in trust for the BY: Todd Falasco Attorneys process against it may be LLC to: the LLC, 225-31 114th of the LLC upon whom within twenty (20) days after registered holders of ACE Se- for Plaintiff 53 Gibson Street served. SSNY shall mail copy Avenue, Cambria Heights, process against it may be service of this Summons, ex- curities Corp., Home Equity Bay Shore, New York 11706 of process to the LLC, 8337 St. -

Working Papers

working papers 2012 The Evolution of School Support Networks in New York City Eric Nadelstern Foreword by Christine Campbell CRPE Working Paper #2012-2 center on reinventing public education University of Washington Bothell 425 Pontius Ave N, Ste 410, Seattle, WA 98109-5450 206.685.2214 • fax: 206.221.7402 • www.crpe.org This report was made possible by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We thank them for their support, but acknowledge that the views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the foundation. CRPE Working Papers have not been subject to the Center’s Quality Assurance Process. THE PORTFOLIO SCHOOL DISTRICTS PROJECT Portfolio management is an emerging strategy in public education, one in which school districts manage a portfolio of diverse schools that are provided in many ways—including through traditional district operation, charter operators, and nonprofit organizations—and hold all schools accountable for performance. In 2009, the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) launched the Portfolio School Districts Project to help state and local leaders understand practical issues related to the design and implementation of the portfolio school district strategy, and to support portfolio school districts in learning from one another. A Different Vision of the School District Traditional School Districts Portfolio School Districts Schools as permanent investments Schools as contingent on performance “One best system” of schooling Differentiated system of schools Government as sole provider Diverse groups provide schools Analysis of Portfolio District Practices To understand how these broad ideas play out in practice, CRPE is studying an array of districts (Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Denver, Hartford, New Orleans, and New York City) that are implementing the portfolio strategy. -

College and Career Readiness in Context

COLLEGE AND CAREER READINESS IN CONTEXT Leslie Santee Siskin Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, & Human Development, New York University October 8th, 2013 COLLEGE AND CAREER READINESS IN CONTEXT Leslie Santee Siskin Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, & Human Development, New York University Introduction Three years ago the Board of Regents launched an educational sea change in New York State. The goal of the Regents is very straightforward: all students should graduate from high school with the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed in college and careers. –New York State Education Commissioner John King, in News and Notes, March 2013 The shift in education reform to a goal of college and career readiness for all students is indeed, as Commissioner King describes it, a sea change that has been embraced widely across the country. It has been taken up by the White House; U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan proclaimed President Obama’s new mission for schools “to ready students for career and college—and without the need for remediation” (2010 Address to College Board). It has echoed across district offices, including the New York City Department of Education (NYC DoE), which laid out this new vision as early as 2004 and where Chancellor Dennis Walcott has called for a new standard: “no longer a high school diploma, but career and college readiness.” It is even written on the subway walls, in English and Spanish as NYC DoE ads proclaim: “We’re not satisfied just teaching your children basic skills. We want them prepared for college and a career.” It has penetrated public opinion, even before the subway ads; the intent to go to college is now almost universal among entering high school students and their families. -

One-Hit Wonders: Why Some of the Most Important Works of Modern Art Are Not by Important Artists

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES ONE-HIT WONDERS: WHY SOME OF THE MOST IMPORTANT WORKS OF MODERN ART ARE NOT BY IMPORTANT ARTISTS David W. Galenson Working Paper 10885 http://www.nber.org/papers/w10885 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2004 The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2004 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. One Hit Wonders: Why Some of the Most Important Works of Art are Not by Important Artists David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 10885 November 2004 JEL No. J0, J4 ABSTRACT How can minor artists produce major works of art? This paper considers 13 modern visual artists, each of whom produced a single masterpiece that dominates the artist’s career. The artists include painters, sculptors, and architects, and their masterpieces include works as prominent as the painting American Gothic, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D. C. In each case, these isolated achievements were the products of innovative ideas that the artists formulated early in their careers, and fully embodied in individual works. The phenomenon of the artistic one-hit wonder highlights the nature of conceptual innovation, in which radical new approaches based on new ideas are introduced suddenly by young practitioners. David W. Galenson Department of Economics University of Chicago 1126 East 59th Street Chicago, IL 60637 and NBER [email protected] 3 The history of popular music is haunted by the ghosts of scores of singers and groups who made a single hit song and were never heard from again. -

Download Newsletter Issue 1

2011 Ideas....Policies....Programs.....Solutions David Rubel Associates I am pleased to send you a newsletter that describes recent projects of my consultant practice. Over the past five years, much of my work has focused on two areas: helping New York City children receive the education services they are entitled to under the law; developing programs that help adults achieve economic self sufficiency. The overall goal of my practice remains the same: how to transform ideas into programs that work. The programs begin as well researched concept papers. The concept papers usually have bipartisan appeal; they are well received no matter who is Mayor, Governor or President. They also include recommendations based on better utilization of available dollars instead of having to undertake the burden of raising new dollars. My approach is rooted in the convergence of social policy and muckraking. I have also learned that connections between seemingly unrelated areas of intervention and need offer us fertile ground for conceiving new programs. Equally important, an analysis of problems and solutions should be conducted within a totality of societal David Rubel relationships. Finally, all activity must stand up to a measurable test of usefulness and effect. The ideas policies programs solutions projects described here have been designed so the practitioners who run community development and human services organizations can plug them into their day to day work. Sincerely, David Rubel 2 1. Helping New York City Parentally Placed Children in Private Schools Access the Special Education Services they are Entitled to Under Federal and State Law In New York State, children with learning differences attending private schools are entitled to most of the same services as children attending public schools.