Case Notes Thomas L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Series Descriptions

[The records in this collection are arranged by theme and in some cases format. Themes were identified by analyzing folder titles. Topic modeling analysis of the folder titles in these themes confirmed that they logically reflect the data contained therein. Descriptions include information pertaining to: how the records were acquired by the company (i.e., natural accumulation, created by the company, targeted collection), subjects present, types of material, strengths and weaknesses, historical context, and cross references. When possible, terms from the Library of Congress Authorities Thesaurus and Art and Architecture Thesaurus were used. Not all series are described.] (I.) CORPORATE AND THIS SERIES CONSISTS OF RECORDS CREATED AND ACCUMULATED BY GENERAL EXECUTIVE LEVEL AND EXTRA-DIVISIONAL OFFICES, SUCH AS THE BOARD 1920-1994 OF DIRECTORS, AND RECORDS THAT ARE GENERAL IN SCOPE. (I.A.) Awards and Accolades This series consists of awards and accolades received by the company and its 1929-1983 officers from a variety of organizations. It includes certificates, commendatory letters, and correspondence (letters, memos, telexes, telegraphs, etc.). For photographs pertaining to this series, see “Photographs, Corporate and General”. (I.B.) Bankruptcy This series consists of records created and accumulated during the company's 1990-1994 bankruptcy, and includes records pertaining to the transfer of assets to Delta Airlines. (I.C.) ByLaws and Policies This series consists of corporate bylaws (by-laws) and policies and includes 1927-1987 correspondence (letters, memos, telexes, telegraphs, etc.), certificates of incorporation, and interlocking relationship agreements. See also "Records of the Executive Officers, Secretary" for early development of bylaws and policies; see "Divisions and Affiliates" for bylaws and policies pertaining to specific divisions and affiliates; and see “Personnel, Policies and Procedures” for 1 personnel policies. -

Order 2007-1-9

Order 2007-1-9 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. Issued by the Department of Transportation on the seventeenth day of January, 2007 Caribair, SA Docket OST-2007-26781 Served January 17,2007 Violations of 49 U.S.C. $j§41301 and 41712 CONSENT ORDER This consent order concerns unauthorized holding out and operation of air transportation by Caribair, SA ("Caribair"), a foreign entity based in the Dominican Republic. The unauthorized holding out and operations by Caribair violate the economic licensing requirements of 49 U.S.C. § 41301 and constitute an unfair and deceptive practice and an unfair method of competition in violation of 49 U.S.C. § 41712. This order directs Caribair to cease and desist from future violations and assesses compromise civil penalties of $70,000. Caribair is a provider of air transport services licensed in the Dominican Republic and based at Puerto Plata International Airport in Puerto Plata. In order to engage in air transportation to or from the United States, 49 U.S.C. §41301 requires that a foreign entity hold a permit conferring economic authority from the Department.' Violations of section 41301 also constitute unfair and deceptive practices and unfair methods of competition prohibited by 49 U.S.C. § 41712. An investigation by the office of the Assistant General Counsel for Aviation Enforcement and Proceedings (Enforcement Office) based on a referral from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) disclosed that Caribair conducted I This authority is separate and distinct from the safety authority that such a carrier must obtain from the Federal Aviation Administration. -

Who's Your ALPA Rep & Why It Matters

Who’s Your ALPA Rep & Why It Matters Page 21 Exclusive Q&A with FAA Administrator Huerta Page 17 The Latest on Flight Time/Duty Time Page 25 Why You Don’t Want Sequestration to Happen Page 37 March 2013 Air Line Pilot 1 PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. PRINTED IN A member service of Air Line Pilot. MARCH 2013 • VoluMe 82, NuMbeR 3 COMMENTARY An Interview 4 Take Note With FAA Tell ALPA Your Past Administrator 5 Aviation Matters Huerta ALPA’s Brand of 17 Determination 6 Weighing In Making the Most of Your 15 ALPA Membership FEATURES 17 17 An Interview with About the Cover FAA Administrator An Alaska Airlines B-737 takes off from Ronald Huerta Reagan Washington National Airport. 21 Who’s Your Rep Photo by Eric Davis. & Why It Matters Download a QR CGN reader to your 25 Fighting the smartphone, scan ANC the code, and read the magazine. YTH Cargo ‘Carveout’ YEG Air Line Pilot (ISSN 0002-242X) is pub lished YYC monthly by the Air Line Pilots Association, YVR YHZ Inter national, affiliated with AFL-CIO, CLC. Editorial Offices: 535 Herndon Parkway, Fighting SEA&WhyYWG It Matters YQT YOW YUL PO Box 1169, Herndon, VA 20172-1169. PDX Telephone: 703-481-4460. Fax: 703- 464- The Cargo YYZ 2114. Copyright © 2013—Air Line Pilots MMV MSP ‘ ’ YHM Association, Inter national, all rights Carveout DET PHL LGA reserved. Publica tion in any form without DET MDT JFK ORD TOL MDT permission is prohibited. Air Line Pilot TOL CLE EWR DAY and the ALPA logo Reg. -

This Is the Us Master Pilot Scablist the Unionist's Edition

THIS IS THE US MASTER PILOT SCABLIST THE UNIONIST’S EDITION A SCAB is A Person Who is Doing What You’d be Doing if You Weren’t on Strike. A SCAB takes your job, a Job he could not get under normal circumstances. He can only advance himself by taking advantage of labor disputes and walking over the backs of workers trying to maintain decent wages and working conditions. He helps management to destroy his and your profession, often ending up under conditions he/she wouldn't even have scabbed for. No matter. A SCAB doesn't think long term, nor does he think of anything other then himself. His smile shows fangs that drip with your blood, for he willingly destroys families, lives, careers, opportunities and professions at the drop of a hat. He takes from a striker what he knows he could never earn by his own merit: a decent Job. He steals that which others earned at the bargaining table through blood, sweat and tears, and throws it away in an instant - ruining lives, jobs and careers. ONCE A SCAB, ALWAYS A SCAB - NEVER FORGET! Below are brief notes about legal strikes by organized pilots. 1. Century Airlines 1932: Pilots struck to resist wage reduction by E.L Cord, the patron saint of Frank Lorenzo. 2. TWA 1946: Pilots struck over pay on faster 4 engine aircraft, limited by the provisions of Decision 83. 3. National Airlines 1948: Strike over aircraft safety and repeated violations of the labor contract. 4. Western Airlines 1958: Qualifications of the Flight Engineer. -

ALPA Miami Joint Council Office Records 31 Linear Feet (31 SB) 1935-1968, Bulk 1950-1960

ALPA Miami Joint Council Office Records 31 linear feet (31 SB) 1935-1968, bulk 1950-1960 Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Kathy Makas on June 24, 2014 Accession Number: LR002510 Creator: Air Line Pilots Association Acquisition: The records are made up from two shipments from the Miami regional office from 1-28-1971 and 6-6-1975. Language: Material entirely in English. Access: Collection is open for research. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Restrictions: Researchers may encounter records of a sensitive nature – personnel files, case records and those involving investigations, legal and other private matters. Privacy laws and restrictions imposed by the Library prohibit the use of names and other personal information which might identify an individual, except with written permission from the Director and/or the donor. Notes: Citation style: “ALPA Miami Joint Council Office Records, Box [#], Folder [#], Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Related Material: Two reels from the Riddle MEC have been moved to the Reuther’s Audio-Visual department. PLEASE NOTE: Material in this collection has been arranged by series ONLY. Folders are not arranged within each series – we have provided an inventory based on their original order. Subjects may be dispersed throughout several boxes within any given series. 1 Abstract The ALPA Miami Joint Council Office (JCO) was a regional office for ALPA Region II and councils in the Southeast United States. It was home to several Master Executive Councils (MEC) and Local Executive Councils (LEC) including: Braniff Airways MEC and Council 29, Delta Airlines Council 71, Eastern Airlines MEC and Council 18, National Airlines MEC and Councils 8 and 73, Pan American Airways (PAA) Council 10, Pan American-Grace Airways (Panagra, PNG) MEC and Councils 38 and 83 and Riddle Airlines (RID) MEC and Councils 114 and 134. -

The Flying Adventures of the Puertoricoflyers

The Flying Adventures of the PuertoRicoFlyers By: Galin Hernandez Millie Santiago The Flying Adventures of the PuertoRicoFlyers Chapter 1 ….2008 Jazmynn Trip Chapter 2…..2008 Christmas to Roatan Chapter 3..…2009 Thanksgiving to Panama Chapter 4….2010 Puerto Rico Fly In Chapter 5……2011 Puerto Rico Holiday Trip Chapter 6……2012 Almost Trip Chapter 7……2013 4th Annual Caribbean Trip Chapter 8……2014 Return to El Salvador Written by: Galin Hernandez Photos by: Milagros Santiago Page 1 Jazmynn Trip Chapter 1 (Pre-Flight) ...................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2 (Off I go, to Cozumel) ..................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 3 (Cozumel to Key West) ................................................................................................. 11 Chapter 4 (Cheap Fuel and Grumpy ATC) .................................................................................... 15 Chapter 5 (Family, Friends, Fixing and Flying) ............................................................................ 19 Chapter 6 (Bad Weather and Bad Comms) .................................................................................... 25 Chapter 7 (Clearwater to Cancun via Marathon Key) ................................................................... 29 Chapter 8 (All the way home) ........................................................................................................ 35 ABBREVIATIONS -

Pan Am Records Series Descriptions

PAN AM RECORDS SERIES DESCRIPTIONS [The records in this collection are arranged by theme and in some cases format. Themes were identified by analyzing folder titles. Topic modeling analysis of the folder titles in these themes confirmed that they logically reflect the data contained therein. Descriptions include information pertaining to: how the records were acquired by the company (i.e., natural accumulation, created by the company, targeted collection), subjects present, types of material, strengths and weaknesses, historical context, and cross references. When possible, terms from the Library of Congress Authorities Thesaurus and Art and Architecture Thesaurus were used. Not all series are described.] (I.) CORPORATE AND THIS SERIES CONSISTS OF RECORDS CREATED AND ACCUMULATED BY GENERAL EXECUTIVE LEVEL AND EXTRA-DIVISIONAL OFFICES, SUCH AS THE BOARD 1920-1994 OF DIRECTORS, AND RECORDS THAT ARE GENERAL IN SCOPE. (I.A.) Awards and Accolades This series consists of awards and accolades received by the company and its 1929-1983 officers from a variety of organizations. It includes certificates, commendatory letters, and correspondence (letters, memos, telexes, telegraphs, etc.). For photographs pertaining to this series, see “Photographs, Corporate and General”. (I.B.) Bankruptcy This series consists of records created and accumulated during the company's 1990-1994 bankruptcy, and includes records pertaining to the transfer of assets to Delta Airlines. (I.C.) ByLaws and Policies This series consists of corporate bylaws (by-laws) and policies and includes 1927-1987 correspondence (letters, memos, telexes, telegraphs, etc.), certificates of incorporation, and interlocking relationship agreements. See also "Records of the Executive Officers, Secretary" for early development of bylaws and policies; see "Divisions and Affiliates" for bylaws and policies pertaining to specific divisions and affiliates; and see “Personnel, Policies and Procedures” for 1 personnel policies. -

Air Travel Consumer Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Air Travel Consumer Report Issued: FEBRUARY 1999 Includes data for the following periods: Flight Delays December 1998 January-December 1998 Mishandled Baggage December 1998 January-December 1998 Oversales 3rd Quarter 1998 January-September 1998 Consumer Complaints December 1998 January-December 1998 Office of Aviation Enforcement and Proceedings http://www.dot.gov/airconsumer/ TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Section Page INTRODUCTION ......................…2 Flight Delays Mishandled Baggage Explanation ......................…3 Explanation ....................…..16 Table 1 ......................…4 Ranking--Month ....................…..17 Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Ranking--YTD ....................…..18 Operations Arriving On Time, by Carrier Table 1A ......................…5 Oversales Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Explanation ....................…..19 Operations Arriving On Time and Carrier Rank, by Month, Quarter, and Data Base to Date Ranking--Quarter ....................…..20 Table 2 ......................…6 Ranking--YTD ....................…..21 Number of Reported Flight Arrivals and Per- centage Arriving On Time, by Carrier and Airport Consumer Complaints Table 3 ......................…8 Explanation ....................…..22 Percentage of All Carriers' Reported Flight Complaint Tables 1-5 (Month) ..............23 Operations Arriving On Time, by Airport and Summary, Complaint Categories, U.S. Airlines, Time of Day Incident Date, and Companies Other Than Table 4 .....................…9 -

To Include Flight Attendants Within Government the Definition Of

- ' 0 x ^ 2 TO INCLUDE FLIGHT ATTENDANTS WITHIN GOVERNMENT THE DEFINITION OF “ AIRM AN” Storage ----- — H E A R I N G BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON JV TE RST ATE AND FOREIGN COMMERCE m □ c HOU SE OE RE PR ESEN TA TIVE S ru H EIGH TY -SE VE NT H CONGRESS DC c a SE CO ND SE SS IO N □ □ ON IT H H.R . 8160, H.R . 8327, an d H.R . 8334 < ILLS TO AM EN D SE CT IO N 10 1(7) O F T H E FED ER A L AV IATION CT OF 1058, SO AS TO IN CLU DE FL IG H T A TT EN DANTS W IT H IN TH E D EFIN IT IO N OF “A IR MAN ” MAY 1, 1002 P ri nte d fo r th e us e of th e Com mitt ee on In te rs ta te a nd Fo re ig n Co mm erc e U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTIN G OF FIC E 83870 0 WASHINGTON : 1962 COMMITTEE ON INTE RSTA TE AND FOREIGN COMMERCE OR EN HA RR IS, Arkansas, Chairman JO HN BE LL WILL IAMS , Mississippi JO HN B. BENNETT , Michigan PETER F. MA CK, J r., Illinois WILLIAM L. SP RI NGER , Illinois KENNETH A. RO BE RT S, Alabam a PAUL F. SC HE NC K, Ohio MO RO AN M. MO UL DE R, Missouri J. AR TH UR YO UN GE R, California HA RL EY O. STAG GERS, West Virginia HAROLD R. -

Reference Guide Bonbini Bonbini! Welcome to Aruba

Bonbini referenCe guIde Bonbini Bonbini! Welcome to Aruba. The word is ours, but we like to think the meaning is universal. As you explore, as you get to know Aruba, you’ll soon begin to notice the smiling faces everywhere. Aruba, as any traveler here will tell you, must surely be among the most welcoming places on earth. Aruba enjoys the highest repeat visitor rate of any Caribbean destination. More than half of our loyal visitors return year after year. Aruba also welcomes first time visitors by working very hard to offer the best hotels, activities, spas and the warmest smiles of anywhere in the Caribbean. 1 Table of Contents about aruba . 04 WeddIngs and Honeymoons . 20 Our happy island Online bridal registry Our friendly people Family and children’s programs Our government Meetings and conferences As a vacation destination Special needs travelers When to visit sHoppIng . 23. ports of entry . 05 nIgHtlIfe . 23. Queen beatrix International airport Casinos Air connections Local hang-outs Aruba Cruise terminal CuIsIne . 24. entry reQuIrements . 06 adventure in Aruba is most often found in a discovery Restaurants Aruba Immigration of the unexpected. Visitors to the island delight in Aruba gastronomic association Aruba Customs Restaurants with special features the amenities of world class hotels while also taking u .s . pre-clearance Authentic aruban cuisine advantage of the opportunity to plot their own road in Aruba. The u .s . passport requirements where to stay . 26. sophistication of our leeward side is rivaled only by the dramatic natural Canada Customs An Resorts/Hotels and historic sites that can be found throughout the island and especially Calendar of events . -

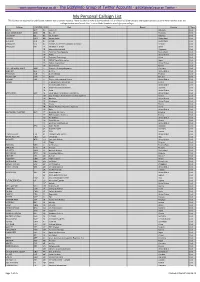

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type GINTA GNT 0A Amber Air Lithuania Civil BLUE MESSENGER BMS 0B Blue Air Romania Civil CATOVAIR IBL 0C IBL Aviation Mauritius Civil DARWIN DWT 0D Darwin Airline Switzerland Civil JETCLUB JCS 0J Jetclub Switzerland Civil VASCO AIR VFC 0V Vietnam Air Services Company (VASCO) Vietnam Civil AMADEUS AGT 1A Amadeus IT Group Spain Civil 1B Abacus International Singapore Civil 1C Electronic Data Systems Switzerland Civil 1D Radixx United States Civil 1E Travelsky Technology China Civil 1F INFINI Travel Information Japan Civil 1G Galileo International United States Civil 1H Siren-Travel Russia Civil CIVIL AIR AMBULANCE AMB 1I Deutsche Rettungsflugwacht Germany Civil EXECJET EJA 1I NetJets United States Civil FRACTION NJE 1I NetJets Europe Portugal Civil NAVIGATOR NVR 1I Novair Sweden Civil PHAZER PZR 1I Sky Trek International Airlines United States Civil Sunturk 1I Pegasus Hava Tasimaciligi Turkey Civil 1I Sierra Nevada Airlines United States Civil 1K Southern Cross Distribution Australia Civil 1K Sutra United States Civil OPEN SKIES OSY 1L Open Skies Consultative Commission United States Civil