Rhetoric As Resistance: Discursive Contestation and the 1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News 2-9-11.Indd

www.thedavidsonian.com DAVI D SON COLLEGE WE D NES D AY , FEBRUARY 9, 2011 VOLUME 102, NUMBER 15 “Dash for Davidson” Meets Success Chambers Bell KATIE LOVETT Staff Writier Chimes Again The “Dash for Davidson” campaign re- ceived a much-anticipated victory Monday night as Gerard Dash ’12 was named the Student Government Association’s (SGA) President for the 2011-2012 academic year. Yet, long before this year’s initial interest meeting for Category II Elections on January 25th, Dash had been committed to making his mark upon the Davidson community. Dash dedicated the first three years of his Davidson career to service for the SGA. His past positions include Freshman Class Senator ERI C SA W YER (2008-2009), Council Chairman (2009-2010) Staff Writer and Student Body Vice President alongside President Kevin Hubbard (2010-2011). In ad- Last week the Chambers bell stopped dition to these roles, he served on official col- ringing, and members of the Physical Plant lege committees, such as the Strategic Plan corrected the problem in several days. The Implementation Team, Council for Campus bell has been inoperative in the past for vary- and Religious Life (CCRL), National Pan- ing lengths of time. It was donated to the col- Hellenic Council Expansion Committee and lege in 1922 to replace its predecessor, which Public Safety Committee, while also holding was destroyed when the old Chambers build- the position of Union Board Treasurer from ing burned down in 1921. 2009 to 2010. “All mechanical equipment will fail from The recently elected president’s experi- time to time,” said Jerry Archer, Physical ence can be seen in the many changes he has Plant. -

GRAMMY U Presents ALBUM REVIEW: KANYE WEST – “MY BEAUTIFUL DARK TWISTED FANTASY” by LESLEY GWAM CONTINUED from MAIN PAGE

GRAMMY U Presents ALBUM REVIEW: KANYE WEST – “MY BEAUTIFUL DARK TWISTED FANTASY” BY LESLEY GWAM CONTINUED FROM MAIN PAGE Anyone who has read my blog (http://hiphopheadmistress.wordpress.com), knows that I absolutely adore Kanye West. So just like any other Yeezy fanatic, I rushed to my nearest music store to purchase My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy on November 22. To be completely honest, I was skeptical about purchasing West’s sixth studio release, because I loathed 808s & Heartbreak (the auto-tune is too much for my senses to handle. I like my rappers to rap, and my singers to sing, unless you’re Queen Latifah and can do both. But this is a discussion for another Wednesday Word). I was quickly won over, however, by his weekly G.O.O.D. Friday releases from kanyewest.com, particularly “Chain Heavy” and “The Joy.” While My Dark Twisted Fantasy does contain a fair amount of auto-tune, it is nevertheless a great album. I must say however, it is imperative to listen to the album multiple times to really grasp Kanye’s vision – a vision that I can’t say I’ve been able to fully comprehend yet. The album opens with “Dark Fantasy,” which serves as an extended album introduction, and features none other than record release date rival, Nicki Minaj as its narrator. The full bodied instrumental kicks in shortly after the one-minute mark, and the grandiose chorus only adds to the melody. While Kanye may have gotten a bit overzealous with the cameo appearances on “All of the Lights,” (the song’s liner notes credit Rihanna, Alicia Keys, Ryan Leslie, Fergie, John Legend, Charlie Wilson, Elton John, Kid Cudi, Elly Johnson and The-Dream with vocal credits), its emphasis on live instruments makes this song a standout number. -

Race, Gender, Class & Identity Through Rap Music

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2018-01-01 Yeezy Taught Me: Race, Gender, Class & Identity Through Rap Music April Marie Reza University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Reza, April Marie, "Yeezy Taught Me: Race, Gender, Class & Identity Through Rap Music" (2018). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 154. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/154 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YEEZY TAUGHT ME: RACE, GENDER, CLASS & IDENTITY THROUGH RAP MUSIC APRIL MARIE REZA Master’s Program in Communication APPROVED: Richard Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Arthur Aguirre, Ph.D. Dennis Bixler-Marquez, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by April Marie Reza 2018 DEDICATION For my family, Mom, Dad, Eric, Dani, and Victor. I wouldn’t be where I am today, without your love and support. YEEZY TAUGHT ME: RACE, GENDER, CLASS & IDENTITY THROUGH RAP MUSIC by APRIL MARIE REZA, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my family for their constant support throughout my education. -

Eastern Progress

SETBACKS Colonels lose first home game of season, fall to COLLECTORS Tennessee State in double overtime B6 Campus roomates collect law enforcement badges from across Kentucky and the country B1 THE EASTERN PROGRESS www.easternprogress.com © 2012 Richmond, KY Student publication of Eastern Kentucky University since 1922 12 pages, Thursday, February 2, 2012 Lack of on-campus apartments displaces international students By JACQUELINE HINKLE to American food.” [email protected] James Street, the acting executive vice president and administrator, said there are still options avail- Following the demolition of the Brockton apart- able on campus for students to live during the con- ments, many students have found themselves in struction of the new dorm that he said will provide need of new housing options either on or off cam- a desired residence for international students. He pus; international students are having a particular- also said the school hosted an apartment fair pri- ly diffi cult time. Additionally, Student Government or to the evacuation of Brockton for the residents. Association has passed a resolution in support of “Th e new dorm will be two to four bedroom an apartment listing on its website to help students. suite style,” Street said. “In the mean time there are “Th e main problem that international students still some units available in Brockton.” are having is fi nding housing with their own kitch- Kenna Middleton, director of housing, said all en, which is what Brockton provided,” said student of Brockton is not torn down. Th ere are 24 units senator Bong Han Lee, 19, environmental health remaining on the complex. -

FSU ETD Template

Florida State University Libraries 2016 Of the Out of Style Jeff Hipsher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES OF THE OUT OF STYLE By JEFF HIPSHER A Thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2016 Jeff Hipsher defended this thesis on April 15, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: David Kirby Professor Directing Thesis Barbara Hamby Committee Member Andrew Epstein Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii for Sarah iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Poems in this manuscript previously appeared in or are forthcoming from The Boston Review and The Common. An early version of this manuscript was one of three finalists for the Poetry Society of America‘s 30 and Under Chapbook Fellowship. I am deeply grateful for the patience and love of my wife, Sarah Cassidy Hipsher. My parents, Paula and Everett Ison, for putting up with me. Don and Margaret Cassidy for the same. All my Hipsher, Cassidy, Ison, Garcia, and Chavez families. Much love to Timothy Donnelly, Chuch O‘Neal, Adam Day, A.H. Jerriod Avant, Mikayla Avila Vila, Yolanda Franklin, Cocoa Williams, Gary Jackson, Chris Michaels, Dan Sack, Hannah Gamble, Douglas Kearney, Nick Sturm, Jeremy Clark, Nick Sturtzel, Rob Johnson, Wendy Xu, Alexis Orgera, Michael Miles, Tristan Child, Mark Hensel, Muriel Leung, and Josh & Jessie English for their invaluable insight, guidance, support, and friendship. -

Kanye West I Love It Clean Version Mp3 Download Kanye West I Love It Clean Version Mp3 Download

kanye west i love it clean version mp3 download Kanye west i love it clean version mp3 download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67a4eac30b2dcaf0 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Best of Kanye West Dj Mixtape ( New & Old Songs) Mixtape Title : Kanye West Greatest Hits Type : Kanye West Hip Hop Compilation Mixtape Tags : best of kanye west dj mix download, kanye west mix, kanye west mixtape, download best of kanye west, kanye west dj mix mp3 download 2019. Year 2021 DJ Mix Description : Kanye Omari West is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, record producer, entrepreneur, and fashion designer. His musical career has been marked by dramatic changes in styles, incorporating an eclectic range of influences including soul, baroque pop, electro, indie rock, synth-pop, industrial, and gospel. Wikipedia. Playing these Kanye West songs. Gold Digger I Love It Stronger Runaway Ni**as In Paris Fade All of the Lights Heartless Flashing Lights Power Mercy Famous Can’t Tell Me Nothing FourFiveSeconds Jesus Walks Through the Wire Otis All Falls Down Good Life Love Lockdown Ultralight Beam No Church in the Wild Black Skinhead Father Stretch My Hands Pt. -

Uppsats På Grundnivå Independent Degree Project First Cycle

Uppsats på grundnivå Independent degree project first cycle Litteraturvetenskap 15p Literature 15p Så klingar hennes röst som ett eko genom alla himlar En studie i Silvana Imams anknytning till lyriska företrädare, med fokus på Edith Södergran. Antonia Savva 1 MITTUNIVERSITETET Institutionen för Humaniora Examinator: Anders E. Johansson, [email protected] Handledare: Anders S. Johansson, [email protected] Författare: Antonia Savva, [email protected] Utbildningsprogram: Litteraturvetenskap C, 30 hp Huvudområde: Litteraturvetenskap Termin, år: VT, 2017 2 Innehållsförteckning 1. Inledning………………...……………………………………..4 2. Syfte, process och metod……………………...……………….5 3. Bakgrund……………………………………………………….6 3.1. Södergranforskningen……….………………………...6–7 3.2. Silvana Imam…………………….……………………7–9 4. Analys…………………………………………………………10 4.1. Subjektspositionen och scenen...…………..……….10–14 4.2. Blomstertid och kristussymboler…………………....14–20 4.3. Hon är allt för mig – kvinnoporträtt……………......20–26 5. Avslutande diskussion och sammanfattning…………….........27 6. Referenser………………………………………………...28–29 7. Appendix…………………………………………………30–35 3 1. Inledning Silvana Imam har de senaste åren blivit en ikon inom svensk rap och det är många saker som särskiljer henne från hennes samtida kollegor. Hon är en homosexuell kvinna som anammar rapens hybrisliknande jargong som målar upp jaget till gudomliga proportioner. Något annat som ställer henne i särställning är det lyriska språket som öppnar hennes texter för otaliga tolkningsmöjligheter. Rapmusiken är känd -

A Deep Dive Into the Magnum Opus That Saved Kanyeâ•Žs Career

Backstage Pass Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 12 2019 Redemption: A Deep Dive Into the Magnum Opus That Saved Kanye’s Career Graham D. McLaren-Finelli University of the Pacific, [email protected] Graham McLaren-Finelli (2022) is pursuing a degree in Music Industry Studies. This article was written as part of the curriculum for the Bachelor of Music in Music Management and the Bachelor of Science in Music Industry Studies at University of the Pacific. Each student conducted research based on his or her own areas of interest and study. To learn more about the program, visit: go.pacific.edu/musicindustry All images used from album covers are included under the Fair Use provision of U.S. Copyright law and remain the property of their respective copyright owners. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/backstage-pass Part of the Arts Management Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Music Commons, and the Radio Commons Recommended Citation McLaren-Finelli, Graham D. (2019) "Redemption: A Deep Dive Into the Magnum Opus That Saved Kanye’s Career," Backstage Pass: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/backstage-pass/vol2/iss1/12 This Concert and Album Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Conservatory of Music at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Backstage Pass by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McLaren-Finelli: Redemption: A Deep Dive Into the Magnum Opus That Saved Kanye’s C Redemption: A Deep Dive Into the Magnum Opus That Saved Kanye’s Career By Graham McLaren-Finelli My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was a turning point for Kanye West. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

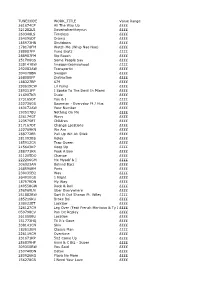

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261674CP All the Way up Гггг 321282LS Iloveitwhentheyrun Гггг 269348LS Timeless Гггг

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261674CP All The Way Up ££££ 321282LS Iloveitwhentheyrun ££££ 269348LS Timeless ££££ 254095DT Drama ££££ 185973HN Shutdown ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 288987FP Yung Bratz ££££ 288987FM Rip Roach ££££ 251706GS Some People Say ££££ 338141BW Imsippinteainyohood ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 394078BN Swagon ££££ 268080FP Distraction ££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 273165DT You & I ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 143172AW Your Number ££££ 190517BU Nothing On Me ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 217167DT Change Locations ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 288772ER Pull Up Wit Ah Stick ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 306923AN Behind Barz ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 239035EQ Way ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 187979DN My Way ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 256969LN Uber Everywhere ££££ 251882BW Sort It Out Sharon Ft. Wiley ££££ 285216KU Broke Boi ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 326127CM Leg Over (Feat French Montana & Ty Dolla)££££ (Remix) 059798CV Pon De Replay ££££ 261050BU Location ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 338141CN Skin ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 226119CM Overtime ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 280926KQ Playa No More ££££ 156278GR I Need Your Love ££££ 289817KU Slipknot ££££ 318501EW Ski Mask ££££ 156551CN Alright -

Merrimack College at the Intersection of Rock and Rap Analyzing The

Merrimack College At the Intersection of Rock and Rap Analyzing the History of Fusions Dillon Cloonan Senior Capstone for Music Major Dr. Laura Pruett May 15, 2020 1 The start of a brand-new decade never fails to feel refreshing. It is a time to reflect on the ups and downs of the past ten years, and mentally wipe the slate clean as the fresh decade approaches. Preparing for what the future will bring is an exciting thought, and what will come next is inevitably unpredictable. The same is absolutely true for music. A decade is a fantastic lens for examining the changes in popular, live and underground music. Every single decade since the 1920’s has brought forth new changes in style, instrumentation, performance and delivery. Some of the most notable of these changes include the emergence of jazz in the 1920’s, the popularization of Big Band in the 40’s, the British invasion in the 60’s, the fight for the legitimacy of rap in the 80’s, and the domination of synths and computer music beginning in the 2000’s among dozens of other examples. However, the most interesting example throughout decades to analyze that was not mentioned is the fusion of rap and rock styles of music in the popular eye beginning in the mid 80’s and 90’s. The alliance of these two styles of music impacted our current landscape for music more dramatically than any other combination. The importance of this specific fusion stretches from the general public’s acceptance of hip-hop itself, and the gateway for other styles of music to be blended with rap, such as country, metal, jazz, and electronic music among others. -

Boxers Boxers, Sweepstakes (Puppy 6‐9) Dogs 11 2 Katandy's Movin on Up

Greater Cincinnati Boxer Club Thursday, October 15, 2020 Boxers Boxers, Sweepstakes (Puppy 6‐9) Dogs 11 2 Katandy's Movin On Up. WS67897901 2/18/2020 Breeder: Lee Morris/Mark Young. Sire: CH Katandy Katydid's Rampin It Up Dam: Katandy's Enchanted Kiss. Owner:Lee Morris. 15 4 3r's Dusty Ford's Back Seat Driver. WS67313501 2/7/2020 Breeder: Ann Teply/Rodney Teply. Sire: GCHB CH Dusty Road's Wild Ride ACT1 Dam: GCH CH 3r's 4d Eleanor Shelby. Owner:Ann teply and rodney teply|Rodney teply. 17 3 Anscha-K Krew Number Nine In A Party Of Ten. WS67588702 2/10/2020 Breeder: Mr. Keith A. Lawson/Mrs. Ann Schach/Ms. Amy Bieri/Charlene Medeiros. Sire: GCH CH Happy Tail's Moment Of Trust CD BN RI AX AXJ NF ACT1 CGC Dam: GCHS CH Jokar N K-Krew's The Dream Lives On At Anscha. Owner:Ann Schach|Kim Schach|Amy Bieri. 19 1 Cinbar's Quarterback At Dunnford. WS67305702 2/3/2020 Breeder: Denise Snyder/Medley Small/Phillip Koenig. Sire: CH Bar-K's Mystic Heir Dam: CH Cinbar's By A Landslide. Owner:Christine Shackelford|Medley Small|Denise Snyder|Phillip Koenig. 21 AB Premier Ps This Is Austin. WS68147002 4/8/2020 Breeder: Lynn St Coeur/Jessica St Coeur. Sire: CH Olympic's Don'T Leave Home Without Him CA Dam: GCHB CH Cheyda Premier Jolene Dont Take My Man. Owner:Jessica St. Coeur|Lynn St.Coeur. Boxers, Sweepstakes (Puppy 9‐12) Dogs 25 1 Streamline N Sapphire's Life Of Royalty.