Towards a Sustainable Urban Future in Oman: Problem & Process Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are You Doing Tomorrow?

WHAT ARE YOU DOING TOMORROW? SHURAMTOURISM.COM BOOK YOUR TRIP WITH US! WWW.SHURAMTOURISM.COM MUSCAT CITY TOUR STOPS HALF DAY FULL DAY STOPS Sultan Qaboos Sultan Qaboos We start off by visiting the exquisite The tour starts like the half day tour. Grand Mosque Grand Mosque Royal Opera House Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque. The tour Royal Opera House Al Alam Palace includes an insight into the different After visiting the Royal Opera House we National Museum Al Alam Palace DURATION Islamic schools and visitors can avail continue drive through Corniche and Muttrah Souq ca.4 hrs of related reading materials at the through old Muscat town to the National DURATION — Grand Mosque Mosque’s library. Afterwards we visit Museum, which offers a wealth of ca.8 hrs the Royal Opera House, Oman’s information about the country’s rich leading global arts and culture centre. — Muscat history, culture and tradition. Enjoy its architectural beauty in a house tour and stroll through the shops Afterwards, we walk a short distance and restaurants in the galleria. to view one of the Sultan’s grand palaces, the Al Alam Palace looking onto We drive through the Corniche and the magnificent 16th century Portu- Old Muscat town to view one of guese Jalali and Mirani Forts. We take the Sultan’s grand palaces, the Al Alam the car to drive to the back of the WWW.SHURAMTOURISM.COM Palace looking onto the magnificent palace for a closer view of the forts. 16th century Portuguese Jalali and Mirani Forts. We take the car to We end our day at Muttrah Souq, where drive to the back of the palace for a you can relish the nostalgic atmosphere closer view of the forts. -

Muscat, Oman Destination Guide

Muscat, Oman Destination Guide Overview of Muscat Muscat is the capital and largest city in Oman, but tourists will find that the mundane activity of the busy modern capital is easily forgotten among the exotic delights of bustling markets, cannon-guarded forts, ornate palaces and historic city harbour. The once important maritime city underwent a resurgence in the 1970s, when the Sultan Qaboos bin Said began to develop museums, mosques and palaces, and worked to restore relics of Muscat's history. Muscat is made up of three cities grown together: the original walled city of Muscat (home to the royal palaces); the former fishing village of Matrah with its maze-like souq; and the commercial and diplomatic area of Ruwi. These areas, along with other districts further from the city centre, each have their own distinct personalities and attractions. Although Muscat is a popular destination for sightseeing tours, many of the attractions are primarily regular fixtures of Omani life. The mosques are important religious sites, the ancient forts are still operated by the military and the sultan's palace is the seat of Oman's government. The beauty of the city is what makes Muscat so alluring, especially near the harbour. The smooth, curved stone architecture is a transition from the rocky landscape to the inviting water of the harbour. Many new buildings have continued with classic Arabic architecture, further protecting the city's legacy from the ravages of the modern world. Muscat is one of the safest, most cosmopolitan and most open-minded cities in the entire Gulf Region and fast becoming a Middle East tourism hotspot. -

Geological and Seismic Evidence for the Tectonic Evolution of the NE Oman Continental Margin and Gulf of Oman GEOSPHERE, V

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Geological and seismic evidence for the tectonic evolution of the NE Oman continental margin and Gulf of Oman GEOSPHERE, v. 17, no. X Bruce Levell1, Michael Searle1, Adrian White1,*, Lauren Kedar1,†, Henk Droste1, and Mia Van Steenwinkel2 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, UK https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02376.1 2Locquetstraat 11, Hombeek, 2811, Belgium 15 figures ABSTRACT Arabian shelf or platform (Glennie et al., 1973, 1974; Searle, 2007). Restoration CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] of the thrust sheets records several hundred kilometers of shortening in the Late Cretaceous obduction of the Semail ophiolite and underlying thrust Neo-Tethyan continental margin to slope (Sumeini complex), basin (Hawasina CITATION: Levell, B., Searle, M., White, A., Kedar, L., Droste, H., and Van Steenwinkel, M., 2021, Geological sheets of Neo-Tethyan oceanic sediments onto the submerged continental complex), and trench (Haybi complex) facies rocks during ophiolite emplace- and seismic evidence for the tectonic evolution of the margin of Oman involved thin-skinned SW-vergent thrusting above a thick ment (Searle, 1985, 2007; Cooper, 1988; Searle et al., 2004). The present-day NE Oman continental margin and Gulf of Oman: Geo- Guadalupian–Cenomanian shelf-carbonate sequence. A flexural foreland basin southwestward extent of the ophiolite and Hawasina complex thrust sheets is sphere, v. 17, no. X, p. 1– 22, https:// doi .org /10.1130 /GES02376.1. (Muti and Aruma Basin) developed due to the thrust loading. Newly available at least 150 km across the Arabian continental margin. The obduction, which seismic reflection data, tied to wells in the Gulf of Oman, suggest indirectly spanned the Cenomanian to Early Maastrichtian (ca 95–72 Ma; Searle et al., Science Editor: David E. -

Welcome to Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar Resort a Guide to Etiquette, Climate and Transportation

EXPERIENCE NEW HEIGHTS OF LUXURY WITH AUTHENTIC OMANI HOSPITALITY WELCOME TO ANANTARA AL JABAL AL AKHDAR RESORT A GUIDE TO ETIQUETTE, CLIMATE AND TRANSPORTATION ETIQUETTE As a general courtesy with respect to local customs, it is highly recommended to dress modestly whilst out and about in Oman. We suggest for guests to cover their shoulders and legs (from the knee up), and to avoid form fitting clothing. CLIMATE Al Jabal Al Akhdar is known for its Mediterranean climate. Temperatures drop during winter to below zero degrees Celsius with snow falling at times, and rise in the summer to 28 degrees Celsius. TRANSPORTATION Kindly be informed that you need a 4x4 vehicle to pass by the check point for Al Jabal Al Akhdar, along with your driving license and car registration papers. If you are not driving a 4x4 vehicle, you may park near the check point and request for us to arrange a luxury 4x4 transfer to the resort. Please contact us at tel +968 25218000 for more information. TOP 10 FUN THINGS TO DO IN AL JABAL AL AKHDAR 1. Kids Camping 2. Rock Climbing 3. Wadi of Waterfalls Hike 4. Via Ferrata Mountain Climbing 5. Stargazing 6. Cycling Tours 7. Three Village Adventure Treks 8. Sundown Journey Tour 9. Morning Yoga 10. Archery Lessons DIRECTIONS TO ANANTARA AL JABAL AL AKHDAR RESORT Seeb MUSCAT Muscat International Airport 15 15 Nizwa / Salalah Exit 15 Jabal Akhdar Hotel Samail 15 15 Jabal Akhdar Hotel FROM MUSCAT 172 KM / 2HR 15MIN Use the Northwest expressway out of Muscat heading towards Seeb, and turn off at the Nizwa/Salalah exit and continue following signs towards Izki / Nizwa. -

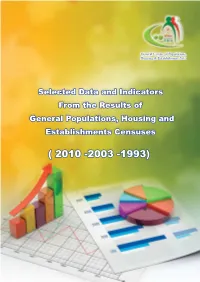

Selected Data and Indicators from the Results of General Populations, Housing and Establishments Censuses

General Census of Populations, Housing & Establishment 2010 Selected Data and Indicators From the Results of General Populations, Housing and Establishments Censuses ) 2010 -2003 -1993( Selected Data and Indicators From the Results of General Populations, Housing and Establishments Censuses (2010 - 2003 - 1993) His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said Foreword His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said, may Allah preserve Him, graciously issued the Royal Decree number (84/2007) calling for the conduct of the General Housing, Population and Establishments Census for the year 2010. The census was carried out with the assistance and cooperation of the various governmental institutions and the cooperation of the people, Omani and Expatriates. This publication contains the Selected Indicators and Information from the Results of the Censuses 1993, 2003 and 2010. It shall be followed by other publications at various Administrative divisions of the Sultanate. Efforts of thousands of those who contributed to census administrative and field work had culminated in the content of this publication. We seize this opportunity to express our appreciation and gratitude to all Omani and Expatriate people who cooperated with the census enumerators in providing the requested information fully and accurately. We also wish to express our appreciation and gratitude to Governmental civic, military and security institutions for their full support to the census a matter that had contributed to the success of this important national undertaking. Likewise, we wish to recognize the faithful efforts exerted by all census administration and field staff in all locations and functional levels. Finally, we pray to Allah the almighty to preserve the Leader of the sustainable development and progress His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said, may Allah preserve him for Oman and its people. -

Al Alama Centre

ALAL AMANAALAMAALAMA CENTRECENTRECENTRE MUSCAT,MUSCAT, SULTANATESULTANATE OFOF OMANOMAN HH AA NN DD BB OO OO KK 0 OUR HISTORY – A UNIQUE LEGACY The name “Al Amana” is Arabic for “bearing trust,” which captures the spirit and legacy of over 115 years of service in Oman. The Centre is the child of the Gulf-wide mission of the Reformed Church in America that began in Oman in 1893. The mission‟s first efforts were in educational work by establishing a school in 1896 that eventually became a coeducational student body of 160 students. The school was closed in 1987 after ninety years of service to the community. The mission was active in many other endeavors, which included beginning a general hospital (the first in Oman), a maternity hospital, a unit for contagious diseases, and a bookshop. With the growth of these initiatives, by the 1950‟s the mission was the largest employer in the private sector in Oman. In the 1970‟s the hospitals were incorporated in the Ministry of Health, and the mission staff worked for the government to assist in the development of its healthcare infrastructure. The mission also established centers for Christian worship in Muscat and Muttrah. It is out of these centers that the contemporary church presence for the expatriate community Oman has grown, now occupying four campuses donated by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said. After Oman discovered oil, having a newfound wealth with which to modernize, the mission's activities were either concluded or grew into independent initiatives. However, the desire to serve the people of Oman continued. -

March 2017/ Issue 1

The Newsletter of MB Group of Companies March 2017/ Issue 1 TURQUOISE THE OFFICIAL PETROGAS NETHERLANDS LAUNCHES OPENING OF 365 INJURY FREE M/Y RAZAN 47 YACHT AL BALEED WORK DAYS CONTENTS 1 2 3 4 20 21 22 23 Message from Message from Dr. Mohammed National Day Sahabat Khair Muscat Marathon Paralympics MB Rihalt Club Chairman Editor Al Barwani appointed MBH & MBI & GEC Awards (After office hours) (After office hours) President of “Oman American Business Center”, National Day Musstir 5 7 9 10 25 26 27 28 Fort Lauderdale The offical opening M/Y RAZAN 47M Sukuk: Islamic MB Sports Day MBI Sports Day Ministry of Health MB Health Campaign boat show of AL Baleed Launch Finance Workshop 11 12 13 15 29 30 31 32 Exchange Petrogas MBPS Espresso sessions MBPS Hydrocarbon, Mawarid mining Koller Innovation Chairman Award Program Townhall Management MBPS Bahrain Rawadan Activities Compact E-Drive for Excellence Retreat Operations localization & succession planning milestone 16 17 18 19 33 34 HR Competency HR Internship MB Forum Petrogas Netherlands Petrogas QHSE Official Visit Framework Company of the to UES Rusayl month July 2016 Facilities 365 recordable injury free work days 1 MESSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN MESSAGE FROM EDITOR Dear Colleagues, Despite the persistent economic and financial challenges in 2016, the Group made a number of remarkable achievements during the year. The Sukuk issue by MB Holding in June, Dear Colleagues, secured a much needed liquidity to sustain the business activity in the Group. The opening of a high class Al-baleed We are embarking on a new business year and although Anantara Resort in Salalah is another big accomplishment by 2016 has been very challenging for the group we expect oil Musstir. -

Spatial Prediction of Coastal Flood- Susceptible Areas in Muscat Governorate Using an Entropy Weighted Method

Risk Analysis XII 121 SPATIAL PREDICTION OF COASTAL FLOOD- SUSCEPTIBLE AREAS IN MUSCAT GOVERNORATE USING AN ENTROPY WEIGHTED METHOD HANAN Y. AL-HINAI & RIFAAT ABDALLA Earth Sciences Department, College of Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman ABSTRACT Flooding is one of the most commonly occurring natural hazards worldwide. Mapping and evaluation of potential flood hazards are vital parts of flood risk assessment and mitigation. This study focuses on predicting the coastal flood susceptibility area in Muscat Governorate, Sultanate of Oman. First, it is assumed that the occurrence of a hazard can be determined based on the indicators influencing it. Thus, four indicators were selected and classified into five classes based on their contribution to flood hazard probability; these include ground elevation, slope degree, soil hydrologic group, and distance from the coast. Then, the entropy weighted method was applied to calculate the weights of given indicators in influencing flood hazards. The results were finally aggregated into ArcGIS software and the produced maps were reclassified into five coastal flood susceptibility zones. The results show that the soil indicator has the highest rate of weight in Wilayats Bawshar, Muttrah, Muscat and Qurayyat. While the elevation indicator has the highest rate of flood hazard in Wilayat AlSeeb. The weight results were used then for calculation of flood hazard index which was then classified into five classes of flood hazard susceptibility zones. The results of this work will be very useful in pursuing work on assessing the potential of multiple hazard risk interactions. It is essential to include certain indicators such as land use and land cover in future work, as they play a major role in water infiltration and runoff behaviour. -

Key Facts and Figures on Oman

KEY FACTS AND FIGURES ON OMAN 1. Membership in UNESCO: 10 February 1972 2. Membership on the Executive Board: yes (term expires in 2019) 3. Membership on Intergovernmental Committees or Commissions, etc…: Council of the UNESCO International Bureau of Education (Term expires in 2018). Intergovernmental Coordinating Council of the Programme on Man and the Biosphere (Term expires in 2018). Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for the Development of Communication (Term expires in 2019). Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (Term expires in 2019). Intergovernmental Council for the Information for Al Programme (Term expires in 2021). Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission 4. Your predecessor’s visits to Oman: 3 13 – 14 May 2014: Global Education for All 22 – 25 January 2011: Official visit 15 – 16 December 2012: Official visit 5. Permanent Delegation to UNESCO H. E. Dr Samira Mohamed Moosa Al Moosa, Ambassador, Permanent Delegate of the Sultanate of Oman to UNESCO (29 September 2011) Staff: Mr Nasser Hamed Salim Al Rawahi, Deputy Permanent Delegate and H. E. Ambassador Musa Bin Jaafar Bin Hassan (Adviser). 6. UNESCO Office in Doha Date of establishment: 1976, Doha (Qatar). Member States serviced: Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Yemen. Name of Head: Ms. Anna Paolini (Italy), Director of the Doha Office. 7. National Commission for UNESCO . Established in September 1974 . Chairperson: Dr. Madiha bint Ahmed bin Nasser Al Shaibaniya; Minister of Education . Secretary General: Mr Mohammed Saleem Al Yaqoubi since September 2012. 8. Personalities having a relationship with UNESCO: none 9. UNITWIN/UNESCO Chairs: 1 UNESCO Chair in Seafood Biotechnology, established in 2001 at Sultan Qaboos University, Al-Khod. -

Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Risk

original article Oman Medical Journal [2017], Vol. 32, No. 2 Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Risk Factor Patterns among Omanis with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study Abdul Hakeem Al Rawahi 1*, Patricia Lee2, Zaher A.M. Al Anqoudi3, Ahmed Al Busaidi4, Muna Al Rabaani5, Faisal Al Mahrouqi3 and Ahmed M. Al Busaidi3 1School of Medicine, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 2School of Medicine, Griffith University, Menzies Health Institute, Queensland, Australia 3Department of Primary Health Care, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Al Dakhiliyah, Oman 4Director of Department of Non-Communicable Diseases, Ministry of Health, Oman 5Al Khoudh Health Centre, Directorate General of Health Services, , Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Objectives: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) represents the leading cause of morbidity Received: 6 November 2016 and mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Its incidence and Accepted: 27 December 2016 risk factor patterns vary widely across different diabetic populations. This study aims Online: to assess the incidence and risk factor patterns of CVD events among Omanis with DOI 10.5001/omj.2017.20 T2DM. Methods: A sample of 2 039 patients with T2DM from a primary care setting, who were free of CVD at beseline (2009−2010) were involved in a retrospective cohort Keywords: Incidence; Risk Factors; study. Socio-demographic data and traditional risk factor assessments at the baseline Cardiovascular Disease; were retrieved from medical records, after which the first CVD outcomes (coronary Coronary Heart Disease; heart disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease) were traced from the baseline to Stroke; Type 2 Diabetes; December 2015, with a median follow-up period of 5.6 years. -

Urbanoman EXHIBITION Panel 01 140319.Indd

Research Collection Conference Poster Urban Oman Exhibition Panel 2 - Introduction Dynamic of Growth Author(s): Richthofen, Aurel von; Nebel, Sonja; Eaton, Anne Publication Date: 2014 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-010821752 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library U Introduction Introduction ProjectDynamic of O Rationale R Growth M B A A N N ﺍﺳﻢ ﺍﻟﻤﺸﺮﻭﻉ :ﺃﻧﻤﺎﻁ ﺍﻟﺘﺤﻀﺮ ﻓﻰ ﻋﻤﺎﻥ ﺍﺳﻢ ﺍﻟﻤﺸﺮﻭﻉ ﺍﻟﻤﺠﻤﻮﻋﺔ: ﺃﻧﻤﺎﻁ ﻣﻘﺪﻣﺔﺍﻟﺘﺤﻀﺮ ﻓﻰ ﻋﻤﺎﻥ ﺍﺳﻢ ﺍﻟﻠﻮﺣﺔ: ﺍﻟﻤﺠﻤﻮﻋﺔﺩﻳﻨ: ﺎﻣﻴﻜﻴﺔﻣﻘﺪﻣﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﻤﻮ ﺍﺳﻢ ﺍﻟﻠﻮﺣﺔ: ﺩﻳﻨﺎﻣﻴﻜﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﻤﻮ ﺍﻟﺘﻨﻤﻴﺔ ﺍﻻﻗﺘﺼﺎﺩﻳﺔ ﺍﻟﺴﺮﻳﻌﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﻨﻤﻮ ﻣﺴﻘﻂ ﻛﺠﺰء ﻣﻦ ﻣﻤﺮ ﺣﻀﺮﻱ RAPID ECONOMIC UNBALANCED POPULATION ﺍﻟﺘﻨﻤﻴﺔ ﺍﻻﻗﺘﺼﺎﺩﻳﺔ ﺍﻟﺴﺮﻳﻌﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﻨﻤﻮ ﻓﻲ ﺑﺪﺍﻳﺔ ﺍﻟﻘﺮﻥ 21 ﺗﺴﺎﻫﻢ ﻋﻤﺎﻥ ﻓﻲ ﺧﻠﻖ ﺷﺮﻳﻂ ﺳﺎﺣﻠﻲ ﻋﺎﻟﻲ D DEVELOPMENT AND DENSITY ﺍﻟﺴﻜﺎﻧﻲ ﺍﻟﺘﺤﻀﺮ ﻭﺍﻟﻜﺜﺎﻓﺔ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻁﻮﻝ ﺑﺤﺮ ﺍﻟﻌﺮﺏ، ﺑﺪءﺍ ﻣﻦ ﻣﺴﻘﻂ ﻭﻋﻠﻰ ﻗﺒﻞ ﺍﻛﺘﺸﺎﻑ ﺍﻟﻨﻔﻂ ﻭﺍﻟﻐﺎﺯ ﻓﻲ ﺳﻠﻄﻨﺔ ﻋﻤﺎﻥ (ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻋﺎﻡ 1960) ﻁﻮﻝ ﺧﻂ ﺍﻟﺴﺎﺣﻞ ﺣﺘﻰ ﺻﺤﺎﺭ، ﺣﻴﺚ ﻳﻨﺪﻣﺞ ﺍﻟﺘﺤﻀﺮ ﺃﺧﻴﺮﺍ ﻣﻊ /POPULATION GROWTH The country’s average population density of 9 p ﻗﺒﻞ ﺍﻛﺘﺸﺎﻑ ﺍﻟﻨﻔﻂ ﻭﺍﻟﻐﺎﺯ ﻓﻲ ﺳﻠﻄﻨﺔ ﻋﻤﺎﻥ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻋﺎﻡ ﺍﻋﺘﻤﺪﺕ ﺍﻟﺒﻼﺩ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺻﻴﺪ ﺍﻷﺳﻤﺎﻙ (ﻭﺍﻟﺰﺭﺍﻋﺔ ﻭﺗﺮﺑﻴﺔ 1960ﺍﻟﺤﻴﻮﺍﻥ،) ,sq km (2010) doesn’t reflect the real situation ﺗﻜﺘﻞ ﺍﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮﺓ ﻭﻳﺴﺘﻤﺮﻋﻠﻰ ﻁﻮﻝ ﺍﻟﺨﻠﻴﺞ ﻟﻺﻣﺎﺭﺍﺕ ﺍﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪﺓ Before the discovery of oil and gas in Oman ﺍﻋﺘﻤﺪﺕﻭﺍﻟﺤﺮﻑ ﺍﻟﺒﻼﺩ ﺍﻟﻴﺪﻭﻳﺔ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻭﺍﻟﺘﺠﺎﺻﻴﺪ ﺭﺓ ﻭﻛﺎﻧﺖﺍﻷﺳﻤﺎﻙ ﻋﻤﺎﻥ ﻭﺍﻟﺰﺭﺍﻋﺔ ﻣﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﻭﺗﺮﺑﻴﺔ ﺭﻳﻔﻲ، ﻧﻈﻤﺖﺍﻟﺤﻴﻮﺍﻥ، as the population is concentrated mainly in the . ﻭﺧﺎﺭﺟﻬﺎ. -Y (end of 1960s) the country relied on fishery, ag ﺍﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺎﻭﺍﻟﺤﺮﻑ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻴﺪﻭﻳﺔ ﻗﺒﺎﺋﻞ ﻭﺍﻟﺘﺠﺎﺭﺓ.ﻭﻋﺸﺎﺋﺮ ﻭﻛﺎﻧﺖ ﻳﻌﻴﺸﻮﻥ ﻓﻲﻋﻤﺎﻥ ﻗﺮﻯ، ﻣﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﺭﻳﻔﻲ، ﻭﻣﻌﻈﻤﻬﻢ ﻣﻦ ﻧﻈﻤﺖ -coastal strip. -

Website Reference List.Xlsx

TLS Reference List 16-07-19 Type Project Name Client Project Type Region Completion Year 33kV Project Construction Of New Saham -2, 2x20MVA Primary Substation Majan Electricity Company Substation Al Batinah North Governorate 2016 33kV Project Construction of New Juffrh, 2 x20MVA primary Substation Majan Electricity Company Substation Al Batinah North Governorate 2016 33kV Project Construction of New Mukhailif - 2 , 2x20MVA Primary Substation Majan Electricity Company Substation Al Batinah North Governorate 2016 33kV Project Al Aman Camp at Bait Al Barka Primary 33/11kv Electrical Substation. Royal Court Affairs Substation Al Batinah South Governorate 2012 33kV Project DPC_Construction Of 1x6MVA, 33/11KV Indoor Primary Substation Designate as Al Saan Dhofar Power Company Substation Dhofar Governorate 2016 33kV Project DPC_Construction Of 1x6MVA, 33/11KV Indoor Primary Substation Designate as Teetam Dhofar Power Company Substation Dhofar Governorate 2016 33kV Project DPC_Construction Of 1x6MVA, 33/11KV Indoor Primary Substation Designate as Hakbeet Dhofar Power Company Substation Dhofar Governorate 2016 33kV Project Upgrading Of Al Jiza, Al Quwaiah, Al Ayoon & Al Falaj Primary Sub stations (33/11 KV) at Mudhaibi Mazoon Electricity Company Substation Ash Sharqiyah North Governorate 2015 Construction of 33KV Feeder from Seih Al Khairat Power station to the Proposed 2x10 MVA , 33/11KV Primary S/S at Hanfeet to feed Power Supply to Hanfeet Power Supply to Hanfeet farms - Wilayat 33kV Project Thumrait Rural Areas Electricity Company (Tanweer)