(Scotland) Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Commonwealth House Medal Route

Life is busy, time is precious. But taking 30 Go on, get to your nearest Walking Hub minutes for a walk will help you feel better – Walk the Walk! Challenge yourself – mentally and physically. Even 15 minutes to ‘give it a go’. Grab a friend, grab your will have a benefit, when you can’t find the children and get outdoors! time to do more. Walking helps you feel more energetic and more able to deal with the Here is a handy little table to get you business of life! Walking also helps us to get started during the first few weeks of fitter and at the same time encourages us to walking. Simply mark on the table get outdoors – and it’s right on your doorstep! which Medal Route you walked on which day – can you build up to Gold? At this Walking Hub you will find 3 short circular walks of different lengths – Bronze, Silver & Gold Medal Routes. You don’t need Week Route M T W T F S S any special equipment to do these walks and going for a walk just got easier they are all planned out on paths – see the 1 map and instructions on the inside. Simple pleasures, easily found Let’s go walking Walking & talking is one of life’s simple 2 pleasures. We don’t need to travel far, we can Commonwealth House visit green spaces where Ramblers Scotland we live, make new friends, 3 Medal Routes is a Ramblers Scotland project. Ramblers have been promoting walking and representing the interests of see how things change walkers in England, Scotland and Wales since 1935. -

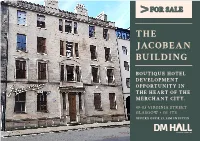

The Jacobean Building

FOR SALE THE JACOBEAN BUILDING BOUTIQUE HOTEL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE HEART OF THE MERCHANT CITY. 49-53 VIRGINIA STREET GLASGOW • G1 1TS OFFERS OVER £1.33M INVITED THE JACOBEAN BUILDING This Grade A listed building dates back to as far as • Rare hotel development 1760 in the times of wealthy merchants in Glasgow opportunity. such as Speirs, Buchanan and Bowmen. Whilst in more recent times it has been used for traditional • Full planning consent commercial purposes these have included yoga granted. studios, offices and for a cookery school. • Within the chic The accommodation is arranged over basement, Merchant City. ground and three upper floors and benefits from a very attractive courtyard to the rear. Within • Offers over £1.33M its current ownership, the building has been invited for the freehold consistently maintained and upgraded since the interest. early 1990s. The main entrance is taken from Virginia Street. The property is on the fringe of the vibrant Merchant City area, with its diverse mix of retailing, pubs, restaurant and residential accommodation much of which has been developed over recent years to include flats for purchase and letting plus serviced apartments. DEVELOPER’S PLANNING PACK The subjects are Category A listed. Full planning permission has been granted for bar and restaurant Our client has provided us with an extensive uses for the ground and basement as well for 18 information pack on the history of the building boutique style hotel rooms to be developed above as well as the planning consents now in place. The on the upper floors. Full information and plans are following documents are available, available on Glasgow City Council’s Planning Portal with particular reference to application numbers - Package of the planning permissions 18/01725/FUL and 18/01726/LBA. -

Courses for Adults.Indd

T: +44 (0)141 330 1860/1853/2772 | E: [email protected] | www.glasgow.ac.uk/centreforopenstudies 01 Courses for Adults 2014-2015 www.glasgow.ac.uk/centreforopenstudies 02 University of Glasgow Centre for OpenUniversity Studies of |Glasgow Welcome Centre for Open Studies | Welcome Welcome Welcome to the Centre for Useful contact information Open Studies 2014 – 2015 Address Telephone Numbers course guide. With over 400 Centre for Open Studies General enquiries courses to choose from on University of Glasgow +44 (0)141 330 1835 many subjects ranging from St Andrew’s Building 11 Eldon Street Brochure requests archaeology to zoology Glasgow +44 (0)141 330 1829 I am sure you will fi nd a G3 6NH course that is right for you. Telephone enrolments (Mon-Fri 10.00-16.30 and from 10.00-19.00 from Mon-Thurs Our courses are part-time day Information Offi ce Hours: 11 August – 16 October) and evening short courses During semester/term time: +44 (0)141 330 1860/1853/2772 Monday to Friday: 09.00 – 17.00 as well as day and half-day (during the enrolment period these Queries about enrolments already made events. Beginner or expert, hours are extended. Please see the +44 (0)141 330 1859/1813 studying for a formal ‘How to enrol’ section on Page 4). Although these hours are applicable qualifi cation or for pleasure, during semester/term time, it would be we are sure you will enjoy advisable to check the Information offi ce your studies with us. is open before making a special journey. -

Strathliving University Life on Your Doorstep

University Life on Your Doorstep www.strath.ac.uk/accommodation Strathliving 02 03 Living in Garnett Hall helped Contents make my first year at Strathclyde one of Welcome to Strathclyde 4 the best years of my Strathclyde Sport 6 life. From the first day Andersonian Library 8 Garnett felt like my Living in halls 10 home away from Our campus 12 home. Undergraduate Accommodation 14 Postgraduate Accommodation 22 At a glance 24 Glasgow 26 Your Application 28 Notes and guidance 28 How to apply 30 What happens next? 31 Admissions Policy 32 Halls checklist 34 Sauchiehall St Strathliving Sauchiehall St 04 05 Buchanan Street Castle St Bus Station Bath St 15 St 16 1 Cathedral St Cathedral St 14 r St N Hanover 12 1 2 10 aylo Choose 4 T 13 2 Buchanan Queen Martha 11 17 3 Street St Street 5 e St Collins St St 18 ose St Rottenrow 5 4 Hop Gardens 6 Strathclyde N Frederick St 3 6 Montr 19 7 John St R Renfield ichmond St George Square 7 8 Geor 9 High St ge St 20 t S r t halls ve John St ose St S 21 Duke St S Frederick St Hano t - live, learn and make life long friends Buchanan Street Montr lbion Ingram St A ueen S Ingram St High St Going to University often means that you will be living away from home for the first time. Q High Street Glasgow t t At Strathclyde, we provide safe and secure accommodation at the heart of the t Central t S . -

West End City Centre North Glasgow Merchant City

MARYHILL RD CHURCHILL DR HAYBURN LN BEECHWOOD DR NOVAR DR 31 HYNDLAND 64 WOODCROFT AVE QUEENSBOROUGHAIRLIE GDNS ST 68 POLWARTH ST HOTELS 48 EDGEHILL RD 63 1 Abode 20 Glasgow Lofts 38 Malmaison Glasgow 57 The Spires LINFERN RD BOTANIC GARDENS 65 NASEBY AVE 2 Apex Hotel GARSCUBE RD 21 GoGlasgow Urban Hotel 39 Marriott Glasgow 58 Travelodge Glasgow Central ROWALLAN GDNS DUDLEY DR 3 Argyll Guest House 22 Grand Central Hotel 40 Max Apartments 59 Travelodge Glasgow Paisley Road MARLBOROUGH AVE AIRLIE ST KEPPOCHHILL RD 28 4 Argyll Hotel 23 Grasshopper Hotel 41 Mercure GlasgowSARACEN ST City 60 Travelodge Queen Street HYNDLAND RD SYDENHAM RD RANDOLPH RD CLARENCE DR FALKLAND ST LAUDERDALE GDNS CHURCHILL DR 5 Artto Hotel 24 Hallmark Hotel Glasgow 42 Millennium Hotel Glasgow 61 Uni Accom - Glasgow Caledonian CROW RD KINGSBOROUGH GDNS PRINCE ALBERT RD 6 Best WesternMARYHILL RD Glasgow City Hotel 25 Hampton Inn by Hilton 43 Motel 1 University, Caledonian Court GREAT WESTERN RD BLAIR ATHOLL AVE VINICOMBE ST 7 Blythswood Hotel 26 Hilton Garden Inn 44 Moxy 62 Uni Accom - University of Glasgow, CLARENCE DR TURNBERRY RD 8 The Brunswick Hotel 27 Hilton Glasgow 45 Novotel Glasgow Centre Cairncross House HAYBURN CRES CROWN RD N CLARENCE DR CRESSWELL ST BELMONT ST 9 Campanile 28 Hilton Glasgow Grosvenor 46 Park Inn by Radisson 63 Uni Accom - University of Glasgow, TURNBERRY RD 10 Carlton George Hotel 29 Holiday Inn Express Riverside 47 Point A Hotel Murano Street PRINCE’S PL 11 CitizenM 30 Holiday Inn Glasgow Theatreland 48 Pond Hotel 64 Uni Accom - University of Glasgow, BYRES RD GARSCUBE RD CROW RD CROWN RD S GREAT WESTERN RD THORNWOOD PL KERSLAND ST 12 Crowne Plaza Glasgow 31 Hotel Du Vin at 49 Premier Inn Argyle Street Queen Margaret Res. -

Postgraduate Researchers of the Built and Natural Environment the First

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RAUmPlan - Repository of Architecture, Urbanism and Planning The First Scottish Conference for Postgraduate Researchers of the Built and Natural Environment Edited by Prof. Charles O. Egbu Michael K.L. Tong PRoBE Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow Scotland, UK 18th - 19th November 2003 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST SCOTTISH CONFERENCE FOR POSTGRADUATE RESEARCHERS OF THE BUILT AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT 18-19 NOVEMBER 2003 GLASGOW CALEDONIAN UNIVERSITY FIRST SCOTTISH CONFERENCE FOR POSTGRADUATE RESEARCHERS OF THE BUILT AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Edited by Prof. Charles O. Egbu and Michael K.L. Tong Glasgow Caledonian University Proceedings of The First Scottish Conference for Postgraduate Researchers of the Built & Natural Environment (PRoBE) Editors: Prof. Charles O. Egbu Michael K. L. Tong Published by Glasgow Caledonian University, School of the Built and Natural Environment City Campus Cowcaddens Road Glasgow, G4 OBA Scotland, UK ISBN: 1-903661-50-1 18th and 19th November 2003 ©2003 Cover design: Olivia Gill, Glasgow Caledonian University ii URBAN AND SUBURBAN PREFERENCES DECOMPOSED FOR A SUSTAINABLE SYNTHESIS Jasna Petric University of Strathclyde, Department of Architecture and Building Science, 131 Rottenrow, Glasgow G4 ONG From a sustainable point of view, city living has a number of advantages over suburban living. In contrast to the normative ways of thinking that support the view that urban areas are sustainable and suburban are not, residential preference of people who are able to exercise their choice may demonstrate greater affiliation with suburban rather than with urban areas. This paper analyses the components of residential preferences (attachment, social and environmental context, physical planning issues, and residential mobility) in the two neighbourhoods of urban and suburban type, which are both attractive for the inhabitants. -

LANE STRATEGY for Glasgow City Centre

LANE STRATEGY for Glasgow City Centre August 2017 Study team: Dele Adeyemo Joost Beunderman Bill Grimes John Lord Willie Miller Ines Triebel Nick Wright LANE STRATEGY GLASGOW CITY CENTRE August 2017 City Centre Regeneration Team DRS - Housing and Regeneration Services Glasgow City Council 231 George Street Glasgow G1 1RX WMUD with Nick Wright Planning Architecture 00 Studio Cascade Pidgin Perfect Yellow Book CONTENTS PAGE Executive Summary i 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Lanes as city centre assets 5 3.0 Learning from elsewhere 21 4.0 Strategic interventions 49 5.0 Planning policy and design guidance 61 6.0 Action projects 65 7.0 Implementation plan 81 8.0 Conclusion 83 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Glasgow City Centre has seen significant regeneration over environment. Recently, lanes have begun to be reintegrated the past twenty years and continues to invest heavily in the into the fabric of cities in new ways. Some are being “greened” quality of the city centre experience. The strategy for the city - renovating them to manage storm water and reduce urban centre is guided by Glasgow City Council’s Getting Ahead of heat island effects. Others are becoming part of the public Change, Glasgow City Centre Strategy and Action Plan 2014– realm either as vibrant pedestrian connections between 19. A fundamental component of the City Centre Strategy streets or as destinations with activities and events. and a key priority is the development and delivery of a city centre lane strategy. This report describes the components Cities across America, in Australia and Canada are beginning of a comprehensive strategy for making the most of the city to activate their lanes in exciting and innovative ways and the centre lanes by creating attractive and active lanes which help report contains a sample collection of those cities involved in to foster a thriving civic life and promote economic growth, a range of different but successful lane projects. -

Engage with the Future in This Newly Completed Grade a Office Development

NEW GRADE A OFFICES TO LET Last remaining suites available Engage with the future in this newly completed grade A office development www.inovoglasgow.com “ inovo has already attracted a cluster of occupiers from the low carbon energy and technology sector as well as enabling industries. The success of inovo to date underlines the competitive advantage companies involved in technology, low carbon and innovation can gain by co-locating and collaborating.” Dr. Lena Wilson Chief Executive, Scottish Enterprise TO LET - New grade ‘A’ offices in the British Council of Offices Scottish Regional award winning building. inovo is one of Scotland’s most sustainable office buildings, offering an EPC rating of ‘A’. Glasgow’s stunning waterfront. Engage with the Glasgow’s recent designation as a Core City will guarantee future investment future in the Citys infrastructure of £4.13 Billion Scotland provides world-class opportunities for investment and growth and has an excellent track record in attracting inward investment from companies recognising the region’s reputation as a global business location. International businesses are attracted by the country’s skills and knowledge base, research pedigree and strong commercial infrastructure. Scotland’s experience in the oil & gas industry and engineering strengths combined with natural resources (206 GW of offshore SSE Headquarters, Waterloo Street, wind, wave and tidal power) give it a competitive advantage over Glasgow. its European and British counterparts. Glasgow is already at the forefront of the renewables industry through the city being the location of choice for SSE, SPR Iberdrola and the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult. Glasgow is becoming internationally recognised as a centre of excellence for low carbon energy. -

High Street and Saltmarket Street Review

High Street and Saltmarket Photo Street Review. February 2018 We are Living Streets Scotland, part of the UK charity for everyday walking. We want to create a walking nation where people of all generations enjoy the benefits that this simple act brings, on streets fit for walking. Living Streets (The Pedestrians’ Association) is a Registered Charity No. 1108448 (England and Wales) and SCO39808 (Scotland). Company Limited by Guarantee (England and Wales), www.livingstreets.scot Company Registration No. 5368409. Registered office: 4th Floor, Universal House, 88-94 Contents page Page 3 – Rational Page 4 – What the space should be Page 6 – Living Streets Scotland Page 6 – Street Audit Page 7 – Summary of audit findings – Home to a community Page 11 – Summary of audit findings – Route for pedestrians Page 18 – Summary of audit findings – A place for visitors Page 21 – Contacts LIVING STREETS SCOTLAND 2 Rational The High Street is the oldest street in Glasgow and has great historical significance. It was the original main street in medieval times along with the Saltmarket, and links the Cathedral precinct in the North to Glasgow Green and the River Clyde in the South. There are many areas of historical interest along the route including St Mungo’s Cathedral, the Necropolis, Tolbooth and Market Cross. There are also a number of key destinations for people making journeys on foot including Glasgow Royal Infirmary, the High Court, Glasgow College and Strathclyde University. Despite the many reasons for people to visit and walk the street, footfall to and through the area is low, and the space feels neglected. -

Explore the City Centre

MARYHILL RD CHURCHILL DR HAYBURN LN BEECHWOOD DR NOVAR DR HYNDLAND WOODCROFT AVE QUEENSBOROUGHAIRLIE GDNS ST POLWARTH ST EDGEHILL RD BOTANIC GARDENS NASEBY AVE LINFERN RD GARSCUBE RD ROWALLAN GDNS DUDLEY DR MARLBOROUGH AVE AIRLIE ST KEPPOCHHILL RD SARACEN ST HYNDLAND RD SYDENHAM RD RANDOLPH RD CLARENCE DR FALKLAND ST LAUDERDALE GDNS CHURCHILL DR CROW RD KINGSBOROUGH GDNS PRINCE ALBERT RD MARYHILL RD GREAT WESTERN RD BLAIR ATHOLL AVE VINICOMBE ST CLARENCE DR TURNBERRY RD CROWN RD N CLARENCE DR HAYBURN CRES TURNBERRY RD CRESSWELL ST BELMONT ST PRINCE’S PL BYRES RD GARSCUBE RD CROW RD CROWN RD S GREAT WESTERN RD THORNWOOD PL KERSLAND ST MONKSCROFT AVE CECIL ST BANAVIE RD GREAT GEORGE ST HIGHBURGH RD CRANWORTH ST SOUTHPARK AVE THORNWOOD GDNS HILLHEAD HILLHEAD ST N GARDNER ST PARTICKHILL RD HIGHBURGH RD ASHTON LANE BANK ST GARDNER ST HYNDLAND AVE OAKFIELD AVE THORNWOOD RD HAVELOCK ST LAUREL ST CAIRD DR KELVINBRIDGE MARYHILL RD GIBSON ST APSLEY ST THORNWOOD TER STEWARTVILLE ST LAWRENCE ST OTAGO ST PARK RD CROW RD WHITE ST FORTROSE ST CRATHIE DR PEEL ST DOWNAHILL ST UNIVERSITY PL GREAT WESTERN RD HYNDLAND ST WHITE ST LAWRIE ST BYRES RD GIBSON ST e CHANCELLOR ST UNIVERSITY AVE tr CHURCH ST CHURCH n KENNOWAY DR KILDONAN DR ce THORNIEWOOD DR y SPRINGBURN RD BURGH HALL ST MUIRPARK ST WEST END cit to WOODLANDS RD THORNIEWOOD AVE MEADOW RD DUMBARTON RD HAYBURN ST DUMBARTON RD TORNESS ST rt PURDON ST DUMBARTON RD o PARK AV ANDERSON ST SANDY RD p KELVINHALL s ROYSTON RD KEITH CT n PARK QUADRANT CRAWFORD ST ra GRANT ST NORTH GLASGOW DUMBARTON RD t KELVIN -

Glasgow Govan - Trade and the Industrial Revolution the Former Parish of Govan Was Very Large and Covered Areas on Both Banks of the Clyde

Shettleston Glasgow Govan - Trade and the Industrial Revolution The former Parish of Govan was very large and covered areas on both banks of the Clyde. On the north side of the river, its boundary included Maryhill, Whiteinch, Partick, Dow- By the 16th century, the city’s trades and craftsmen had begun to wield significant influ- anhill, Hillhead and Kelvinside. On the south side there was Govan, Ibrox, Kinning Park, ence and the city had become an important trading centre with the Clyde providing access Plantation, Huchesontown, Laurieston, Tradeston, Crosshill, Gorbals, Govanhill, West to the city and the rest of Scotland for merchant shipping. The access to the Atlantic Ocean and East Pollokshields, Strathbungo and Dumbreck. xlvi This large area along both sides allowed the importation of goods such as American tobacco and cotton, and Caribbean of the Clyde gives some indication of Govan‟s former importance as the royal home of sugar, which were then traded throughout the United Kingdom and Europe. the former kings of Strathclyde. During the 16th century, many families from outside the Parish were granted permission to settle in the lands at Govan. For instance, Maxwell of The de-silting of the Clyde in the 1770s allowed bigger ships to move further up the river, Nether Pollock settled in what is known today as the Pollock Estate. xlvii From the 16th thus laying the foundations for industry and shipbuilding in Glasgow during the 19th until the 19th century, Govan was a coalmining district with pits in the Gorbals, Ibrox, century. Bellahouston, Broomloans, Helen Street, Drumoyne and at Craigton.