The Old Ludgings of Glasgow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Nuclear Physics Conference 2019 29 July – 2 August 2019 Scottish Event Campus, Glasgow, UK

Conference Handbook International Nuclear Physics Conference 2019 29 July – 2 August 2019 Scottish Event Campus, Glasgow, UK http://inpc2019.iopconfs.org Contents Contacts 3 Local organising committee 4 Disclaimer 4 Inclusivity 4 Social media 4 Venue 5 Floor plan 6 Travel 7 Parking 8 Taxis 8 Accommodation 8 Programme 9 Registration 9 Catering 9 Social programme 10 Excursions 11 Outreach programme 13 Exhibition 14 Information for presenters 14 Information for chairs 15 Information for poster presenters 15 On-site amenities 16 General information 17 Health and safety 19 IOP membership 20 1 | Page Sustainability 20 Health and wellbeing 20 Conference app 21 International advisory committee 21 Site plan 23 Campus map 24 2 | Page Contacts Please read this handbook prior to the event as it includes all of the information you will need while on-site at the conference. If you do have any questions or require further information, please contact a member of the IOP conference organising team. General enquiries Claire Garland Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4840 Mobile: +44 (0)7881 923 142 E-mail: [email protected] Programme enquiries Jason Eghan Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4984 Mobile: +44(0)7884 268 232 Email: [email protected] Excursion enquiries Keenda Sisouphanh Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4890 Email: [email protected] Programme enquiries Rebecca Maclaurin Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4907 Mobile: +44 (0)7880 525 792 Email: [email protected] Exhibition enquiries Edward Jost IOP Publishing Tel: +44(0)117 930 1026 Email: [email protected] Conference chair Professor David Ireland University of Glasgow 3 | Page The IOP organising team will be onsite for the duration of the event and will be located in Halls 1 and 2 at the conference registration desk. -

Fiv Crativ Workspac Studios

FIV CR ATIV WORKSPAC EastWorks is a cutting edge new development that will completely transform the disused Purifier Shed in Dalmarnock, Glasgow into high quality, contemporary office / studio accommodation. The former Purifier Shed is one of just STUDIOS five historic buildings to remain in the area and the regeneration plan seeks to safeguard the Victorian listed façade and revitalise the location. The existing roof structure and columns will be exposed and celebrated. A new steel structure will be installed to support mezzanine levels and open flexible floor space with expanses of curtain wall glazing. The listed façade at the rear will boast original features such as decorative sandstone arches around the windows. The final product will deliver the refurbishment of interesting and innovative spaces, which will comprise 5 standalone units / studios / offices. The building was originally known as the Dalmarnock Purifier Shed developed in the late 1800s. It was opened I for various uses and finally closed in the 1950’s. Since then the building has lain vacant until recently when it was I D ST. supported by the Glasgow 2018 European Championships > 1843 for young people to use the area for an Art Festival. DORA STREET / GLASGOW W ll WORTH IT WelLBEING Provision - Dedicated modern accessible shower facilities, high quality changing areas, drying rooms with benches and hooks, lockers, WCs including accessible toilet located at both ground and mezzanine levels with high quality finishes - Service tails for future tea point/kitchen installation - 26 car spaces including 3 accessible spaces - Electric car charging points - Ample cycle parking provided - External bench seating and soft landscaping for relaxation areas Open plan office areas with Mezzanine levels in each unit. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Commonwealth House Medal Route

Life is busy, time is precious. But taking 30 Go on, get to your nearest Walking Hub minutes for a walk will help you feel better – Walk the Walk! Challenge yourself – mentally and physically. Even 15 minutes to ‘give it a go’. Grab a friend, grab your will have a benefit, when you can’t find the children and get outdoors! time to do more. Walking helps you feel more energetic and more able to deal with the Here is a handy little table to get you business of life! Walking also helps us to get started during the first few weeks of fitter and at the same time encourages us to walking. Simply mark on the table get outdoors – and it’s right on your doorstep! which Medal Route you walked on which day – can you build up to Gold? At this Walking Hub you will find 3 short circular walks of different lengths – Bronze, Silver & Gold Medal Routes. You don’t need Week Route M T W T F S S any special equipment to do these walks and going for a walk just got easier they are all planned out on paths – see the 1 map and instructions on the inside. Simple pleasures, easily found Let’s go walking Walking & talking is one of life’s simple 2 pleasures. We don’t need to travel far, we can Commonwealth House visit green spaces where Ramblers Scotland we live, make new friends, 3 Medal Routes is a Ramblers Scotland project. Ramblers have been promoting walking and representing the interests of see how things change walkers in England, Scotland and Wales since 1935. -

South Lanarkshire Core Paths Plan Adopted November 2012

South Lanarkshire Core Paths Plan Adopted November 2012 Core Paths list Core paths list South Lanarkshire UN/5783/1 Core Paths Plan November 2012 Rutherglen - Cambuslang Area Rutherglen - Cambuslang Area Map 16 Path CodeNorth Name Lanarkshire - Location Length (m) Path Code Name - Location LengthLarkhall-Law (m) CR/4/1 Rutherglen Bridge - Rutherglen Rd 360 CR/27/4 Mill Street 137 CR/5/1 Rutherglen Rd - Quay Rd 83 CR/29/1 Mill Street - Rutherglen Cemetery 274Key CR/5/2 Rutherglen Rd 313 CR/30/1 Mill Street - Rodger Drive Core233 Path CR/5/3 Glasgow Rd 99 CR/31/1 Kingsburn Grove-High Crosshill Aspirational530 Core Path Wider Network CR/5/4 Glasgow Rd / Camp Rd 543 CR/32/1 Cityford Burn - Kings Park Ave 182 HM/2280/1 Cross Boundary Link CR/9/1 Dalmarnock Br - Dalmarnock Junction 844 CR/33/1 Kingsheath Ave 460 HM/2470/1 Core Water Path CR/9/2 Dalmarnock Bridge 51 CR/34/1 Bankhead Road Water122 Access/Egress HM/2438/1 CR/13/1 Bridge Street path - Cambuslang footbridge 56 CR/35/1 Cityford Burn Aspirational164 Crossing CR/14/1 Clyde Walkway-NCR75 440 CR/36/1 Cityford Burn SLC276 Boundary Neighbour Boundary CR/15/1 Clyde Walkway - NCR 75 1026 CR/37/1 Landemer Drive 147 North Lanarkshire HM/2471/2 CR/15/2 NCR 75 865 CR/38/1 Landemer Drive Core Path93 Numbering CR/97 Land CR/15/3 Clyde Walkway - NCR 75 127 CR/39/1 Path back of Landemer Drive 63 UN/5775/1 Water CR/16/1 Clydeford Road 149 CR/40/1 Path back of Landemer Drive CL/5780/1 304 W1 Water Access/Egress Code CR/17/1 Clyde Walkway by Carmyle 221 CR/41/1 King's Park Avenue CL/3008/2 43 HM/2439/1 -

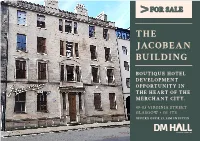

The Jacobean Building

FOR SALE THE JACOBEAN BUILDING BOUTIQUE HOTEL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE HEART OF THE MERCHANT CITY. 49-53 VIRGINIA STREET GLASGOW • G1 1TS OFFERS OVER £1.33M INVITED THE JACOBEAN BUILDING This Grade A listed building dates back to as far as • Rare hotel development 1760 in the times of wealthy merchants in Glasgow opportunity. such as Speirs, Buchanan and Bowmen. Whilst in more recent times it has been used for traditional • Full planning consent commercial purposes these have included yoga granted. studios, offices and for a cookery school. • Within the chic The accommodation is arranged over basement, Merchant City. ground and three upper floors and benefits from a very attractive courtyard to the rear. Within • Offers over £1.33M its current ownership, the building has been invited for the freehold consistently maintained and upgraded since the interest. early 1990s. The main entrance is taken from Virginia Street. The property is on the fringe of the vibrant Merchant City area, with its diverse mix of retailing, pubs, restaurant and residential accommodation much of which has been developed over recent years to include flats for purchase and letting plus serviced apartments. DEVELOPER’S PLANNING PACK The subjects are Category A listed. Full planning permission has been granted for bar and restaurant Our client has provided us with an extensive uses for the ground and basement as well for 18 information pack on the history of the building boutique style hotel rooms to be developed above as well as the planning consents now in place. The on the upper floors. Full information and plans are following documents are available, available on Glasgow City Council’s Planning Portal with particular reference to application numbers - Package of the planning permissions 18/01725/FUL and 18/01726/LBA. -

The Story of the Barony of Gorbals

DA flTO.CS 07 1 a31 1880072327^436 |Uj UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH [y The Library uA dS/0 G5 1^7 Ur<U» JOHN, 1861-192b» THE 5T0RY UP THE bAkONY OF viGRdALS* Date due ^. ^. k ^'^ ^ r^: b ••' * • ^y/i'^ THE STORY OF THE BARONY OF GORBALS Arms of Viscount Belhaven, carved on the wall of Gorbals Chapel, and erroneously called the Arms of Gorbals. Frontispiece. (See page 21) THE STORY OP"' THE BARONY OF GORBALS BY JOHN ORD illustrations PAISLEY: ALEXANDER GARDNER ^ttbliBhtt bB S^vvointmmt to tht IttU Qnun Victoria 1919 LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & CO., LMD. PRINTED BY ALEXANDER GARDNER, PAISLEY. THr LflJRARY PREFACE. Few words are required to introduce this little work to the public of Glasgow. Suffice it to say that on several occasions during the past four years I was invited and did deliver lectures on "Old Gorbals"" to a number of public bodies, among others being the Gorbals Ward Committee, the Old Glasgow Club, and Educational Guilds in connection with the Kinningpark Co-operative Society. The princi- pal matter contained in these lectures I have arranged, edited, and now issue in book form. While engaged collecting materials for the lectures, I discovered that a number of errors had crept into previous publications relating to Old Gorbals. For example, some writers seemed to have entertained the idea that there was only one George Elphinston rented or possessed the lands of Gorbals, whereas there were three of the name, all in direct succession. M'Ure and other historians, failing to distinguish the difference between a Barony and a Burgh of Barony, state that Gorbals was erected into a Burgh of Barony in 1595. -

Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District

Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan June 2016 Published by: Glasgow City Council Delivering sustainable flood risk management is important for Scotland’s continued economic success and well-being. It is essential that we avoid and reduce the risk of flooding, and prepare and protect ourselves and our communities. This is first local flood risk management plan for the Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District, describing the actions which will make a real difference to managing the risk of flooding and recovering from any future flood events. The task now for us – local authorities, Scottish Water, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), the Scottish Government and all other responsible authorities and public bodies – is to turn our plan into action. Pagei Foreword Theimpactsoffloodingexperiencedbyindividuals,communitiesandbusinessescanbedevastating andlonglasting.Itisvitalthatwecontinuetoreducetheriskofanysuchfutureeventsandimprove Scotland’sabilitytomanageandrecoverfromanyeventswhichdooccur. ThepublicationofthisPlanisanimportantmilestoneinimplementingtheFloodRiskManagement (Scotland)Act2009andimprovinghowwecopewithandmanagefloodsintheClydeandLoch LomondLocalPlanDistrict.ThePlantranslatesthislegislationintoactionstoreducethedamageand distresscausedbyfloodingoverthefirstplanningcyclefrom2016to2022.ThisPlanshouldberead inconjunctionwiththeFloodRiskManagementStrategythatwaspublishedfortheClydeandLoch LomondareabytheScottishEnvironmentProtectionAgencyinDecember2015. -

Housing & Development Vacant and Derelict Land Report

60-site sample extract from 2017 vacant and derelict land register Period when site Site Size Local Authority Site Name (If Supplied) Address (If Supplied) East North Site Type Location of Site Owner 1 Owner 2 became Vacant Previous Use of Site Development Potential Datazone (Ha.) or Derelict Stirling BORROWMEADOW BORROWMEADOW FARM, STIRLING 281500 694200 33.8 Derelict Within the countryside Public: Local Authority Not applicable 1981-1985 Community & Health Developable - Medium Term S01013066 North Ayrshire NIL LOCHSHORE NORTH, GLENGARNOCK 232046 653688 29.71 Derelict Within a settlement of < 2,000 Public: Scottish Enterprise Not applicable 1986-1990 Manufacturing Developable - Short Term S01011334 ClackmannanshireKILBAGIE COUNTRYSIDE, KILBAGIE 292740 689958 19.26 Derelict Within the countryside Private: Other Private Not applicable 2015 Manufacturing Developable - Undetermined S01007448 East Renfrewshire ARMITAGE SHANKS Shanks Ind Est, Barrhead 250336 659938 14.67 Derelict Within a settlement of 2,000+ Private: Other Private Not applicable 1991-1995 Manufacturing Developable - Short Term S01008307 East Lothian SITE AT EAST FORTUNE HOSPITAL, EAST FORTUNE, EAST LOTHIAN 355262 679352 13.87 Derelict Within the countryside Private: Other Private Not applicable 1996-2000 Community & Health Developable - Medium Term S01008262 North Ayrshire NACCO PORTLAND ROAD, IRVINE 231431 637571 12.58 Derelict Within a settlement of 2,000+ Unknown Private Not applicable 2008 Manufacturing Developable - Short Term S01011178 Glasgow City NIL S OF 6 VAILA PL. -

Glasgow Effect

Excess mortality in the Glasgow conurbation: exploring the existence of a Glasgow effect James Martin Reid MSci Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD University of Glasgow Faculty of Medicine, Section of Public Health and Health Policy September 2008 ii Abstract Introduction There exists a ‘Scottish effect’, a residue of excess mortality that remains for Scotland relative to England and Wales after standardising for age, sex and local area deprivation status. This residue is largest for the most deprived segments of the Scottish population. Most Scottish areas that can be classified as deprived are located in West Central Scotland and, in particular, the City of Glasgow. Therefore the central aim of this thesis is to establish the existence of a similar ‘Glasgow effect’ and identify if the relationship between deprivation and all cause mortality is different in Glasgow to what is in other, comparable cities in the UK. Methods A method to compare the deprivation status of several UK cities was devised using the deprivation score first calculated by Carstairs and Morris. The population of mainland UK was broken into deciles according to the Carstairs score of Scottish postcode sectors and English wards. Deprivation profiles for particular cities were drawn according to the percentage of the local population that lived in each Carstairs decile. Using data from the three censuses since 1981, longitudinal trends in relative deprivation status for each city could be observed. Analysis of death rates in cities was also undertaken. Two methods were used to compare death rates in cities. Indirect standardisation was used to compare death rates adjusting for the categorical variables of age group, sex and Carstairs decile of postcode sector or ward of residence. -

Capacities & Dimensions

sec.co.uk Scottish Campus, Event Glasgow, Scotland, G3 8YW 3000 248 / [email protected] (0)141 +44 www.sec.co.uk / www.thessehydro.com MARYHILL RD CHURCHILL DR HAYBURN LN BEECHWOOD DR NOVAR DR 32 HYNDLAND 66 WOODCROFT AVE QUEENSBOROUGHAIRLIE GDNS ST 70 POLWARTH ST HOTELS 50 EDGEHILL RD 65 1 Abode 21 Glasgow Lofts 39 Lorne Hotel 59 The Spires LINFERN RD BOTANIC GARDENS 67 NASEBY AVE 2 Anchor Line AparthotelGARSCUBE RD 22 GoGlasgow Urban Hotel 40 Malmaison Glasgow 60 Travelodge Glasgow Central ROWALLAN GDNS DUDLEY DR 3 Apex Hotel 23 Grand Central Hotel 41 Marriott Glasgow 61 Travelodge Glasgow Paisley Road MARLBOROUGH AVE AIRLIE ST KEPPOCHHILL RD 29 4 Argyll Guest House 24 Grasshopper Hotel 42 Max ApartmentsSARACEN ST 62 Travelodge Queen Street HYNDLAND RD SYDENHAM RD RANDOLPH RD CLARENCE DR FALKLAND ST LAUDERDALE GDNS CHURCHILL DR 5 Argyll Hotel 25 Hallmark Hotel Glasgow 43 Mercure Glasgow City 63 Uni Accom - Glasgow Caledonian CROW RD KINGSBOROUGH GDNS PRINCE ALBERT RD 6 Artto HotelMARYHILL RD 26 Hampton Inn by Hilton 44 Millennium Hotel Glasgow University, Caledonian Court GREAT WESTERN RD BLAIR ATHOLL AVE VINICOMBE ST 7 Best Western Glasgow City Hotel 27 Hilton Garden Inn 45 Motel 1 64 Uni Accom - University of Glasgow, CLARENCE DR TURNBERRY RD 8 Blythswood Hotel 28 Hilton Glasgow 46 Moxy Cairncross House HAYBURN CRES CROWN RD N CLARENCE DR CRESSWELL ST BELMONT ST 9 The Brunswick Hotel 29 Hilton Glasgow Grosvenor 47 Novotel Glasgow Centre 65 Uni Accom - University of Glasgow, TURNBERRY RD 10 Campanile 30 Holiday Inn Express Riverside 48 Park Inn by Radisson Murano Street PRINCE’S PL 11 Carlton George Hotel 31 Holiday Inn Glasgow Theatreland 49 Point A Hotel 66 Uni Accom - University of Glasgow, BYRES RD GARSCUBE RD CROW RD CROWN RD S GREAT WESTERN RD THORNWOOD PL KERSLAND ST 12 CitizenM 32 Hotel Du Vin at 50 Pond Hotel Queen Margaret Res. -

Glasgow 2014 Transport Strategic Plan

Transport Strategic Plan Version 1 September 2010 Foreword The Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games will be one of the largest international multi-sporting events that Scotland has ever hosted. Approximately 6500 athletes and team officials from the 71 competing nations and territories of the Commonwealth as well as members of the Commonwealth Games Family, the media and spectators will all be welcomed to Glasgow and other select sites throughout Scotland for 11 exciting days of sport competition and celebration. A crucial element to any successful major games is transportation and the ability to seamlessly facilitate the connectivity between the selected sites for the various client groups attending. This document provides the initial information on the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games strategy for transport, including what we as the Organising Committee aim to achieve, who we are looking to involve to successfully deliver our obligations and how we approach managing our objectives. Our aim is for athletes, spectators and other visitors to come to Glasgow and Scotland and see the city and the nation at its best during these Games. With existing facilities having been upgraded, new venues built and significant infrastructure improvements all completed well in advance of the Games, we will aspire to have transport in and around the Games sites that is safe, secure, reliable and accessible. As we get closer to the Games we plan to publish two further updated editions of the Transport Strategic Plan. Future editions will include: changes incorporated during the various consultation processes; refined information on transport proposals; and emerging best practice following the Delhi 2010 Commonwealth Games, London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games and other major games.