When Brute Force Fails: Strategic Thinking for Crime Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policyspace Is an Empirical Platform, Adjusted for the Case of 333 Brazilian Municipalities Located in the 46 Population Concentration Areas

formato 16x23 cm 8mm de lombada The future is not predictable. It is created. Ipea’s mission Contextually and gradually, with small advances, Enhance public policies that are essential to Brazilian development understandings and adaptations, corrections upon by producing and disseminating knowledge and by advising corrections. The future is negotiated – and emerges the state in its strategic decisions. as an inexorable result of social, institutional and political interactions. Public policies – as a tenuous concept of planning, a vehicle of societal interests – balance, evaluate, contain visions (predominantly public) that guide, direct, drive optimal social development. Future is a scenario of uncertainties. A scenario of social complexity in which policy proposals are made by the society, guided by the managers. Public managers, who seek to mediate policies and their multiplicity of eects, typical eects of complex systems, to the maximum extent that circumstances allow. Given this context, the purpose of this book is to oer an additional tool of modeling to society in general and to managers of the res publica in particular. Not only conceptually, abstractly – but as a concrete tool, available and adaptable. In fact, PolicySpace is an empirical platform, adjusted for the case of 333 Brazilian municipalities located in the 46 population concentration areas. This set of metropolises is home to most of Brazil’s socio-eco- nomic strength, but also its greatest challenges. The core idea of PolicySpace’s platform is to allow the analysis of alternatives – many alternatives – for the implementation of ex-ante public policies. That is, to anticipate, circumstantially, eects, developments, future results of changes, in the present; to analyze interactions between portions of society and institutions, in space and time. -

Chapter 11), Making the Events That Occur Within the Time and Space Of

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: IN PRAISE OF BABBITTRY. SORT OF. SPATIAL PRACTICES IN SUBURBIA Kenneth Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontiers, one of the key histories of American suburbia, marshals a fascinating array of evidence from sociology, geography, real estate literature, union membership profiles, the popular press and census information to represent the American suburbs in terms of population density, home-ownership, and residential status. But even as it notes that “nothing over the years has succeeded in gluing this automobile-oriented civilization into any kind of cohesion – save that of individual routine,” Jackson’s comprehensive history under-analyzes one of its four key suburban traits – the journey-to-work.1 It is difficult to account for the paucity of engagements with suburban transportation and everyday experiences like commuting, even in excellent histories like Jackson’s. In 2005, the average American spent slightly more than twenty-five minutes per day commuting, a time investment that, over the course of a year, translates to more time commuting than he or she will likely spend on vacation.2 Highway-dependent suburban sprawl perpetually moves farther across the map in search of cheap available land, often moving away from both traditional central 1 In the introduction, Jackson describes journey-to-work’s place in suburbia with average travel time and distance in opposition to South America (home of siestas) and Europe, asserting that “an easier connection between work and residence is more valued and achieved in other cultures” (10). 2 One 2003 news report calculates the commuting-to-vacation ratio at 5-to-4: “Americans spend more than 100 hours commuting to work each year, according to American Community Survey (ACS) data released today by the U.S. -

Click Here to Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorPONTEPONTE VED VEDRARAdderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA!! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! has a new home at Here she comes, April 9 - 15, 2020 THE LINKS! 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 ‘Mrs. America,’ Jacksonville Beach Ask about our Offering: 1/2 OFF in Cate Blanchett- · Hydrafacials All Services · RF Microneedling starring · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections FX on Hulu series · Botox & Fillers · Medical Weight Loss Cate Blanchett stars in VIRTUAL CONSULTATIONS “Mrs. America,” premiering Get Skinny with it! Wednesday on FX on Hulu. (904) 999-0977 www.SkinnyJax.com1 x 5” ad Now is a great time to It will provide your home: Kathleen Floryan List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while REALTOR® Broker Associate the home is listed • An edge in the local market LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with WITH ME! ListSecure® I will provide you a FREE America’s Preferred 904-687-5146 Home Warranty for [email protected] your home when we put www.kathleenfloryan.com it on the market. -

2020-05-03-Losangeles.Pdf

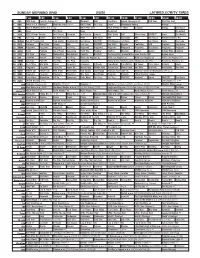

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Workout! AAA Sex Abuse Arnold Strongman Cl. PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Paid Prog. Emeril Motorcycle Racing Hockey 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Omega Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News Basketball Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Coins PROTECT Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Prog. Emeril Fox News Sunday News The Issue AAA Concealer AAA Sex Abuse Greatest Games: NFL 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought Sex Abuse TALCUM Archdiocese of LA Mass AAA Sex Abuse News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Wellness Slim Cycle Tummy AAA Paid Prog. PROTECT New YOU! Organic Foot Pain AAA Prostate Sex Abuse 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Programa Paid Prog. Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Resultados Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Canvasing Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Hubert Joanne Simply Ming Cooking 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Wunderkind Wunderkind Darwin’s Biz Kid$ The Longevity Paradox With Steven Gundry, MD Quincy Jones 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid Prog. NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles 767. -

Evil in the 'City of Angels'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! April 24 - 30, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 W L M C A B L R G R C S P L N Your Key 2 x 3" ad P E Y S W Z A Z O V A T T O F L K D G U E N R S U H M I S J To Buying D O I B N P E M R Z Y U S A F and Selling! N K Z N U D E U W A R P A N E 2 x 3.5" ad Z P I M H A Z R O Q Z D E G Y M K E P I R A D N V G A S E B E D W T E Z P E I A B T G L A U P E M E P Y R M N T A M E V P L R V J R V E Z O N U A S E A O X R Z D F T R O L K R F R D Z D E T E C T I V E S I A X I U K N P F A P N K W P A P L Q E C S T K S M N T I A G O U V A H T P E K H E O S R Z M R “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lewis (Michener) (Nathan) Lane Supernatural Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Magda (Natalie) Dormer (1938) Los Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Tiago (Vega) (Daniel) Zovatto (Police) Detectives Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Evil in the Peter (Craft) (Rory) Kinnear Murder County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Maria (Vega) (Adriana) Barraza Espionage Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘City of Angels’ for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com Natalie Dormer stars in “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels,” All specials are pre-paid. -

Interdisciplinary Journal of the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric

Interdisciplinary Journal of the William J. Perry Volume 14 2013 Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies ISSN: 1533-2535 Special Issue: The Drug Policy Debate FOREIGN POLICY AND SECURITY ISSUES THE DRUG POLICY DEBATE Michael Kryzanek, China, United States, and Latin A Selection of Brief Essays Representing America: Challenges and Opportunities the Diversity of Opinion, Contributors: Marilyn Quagliotti, Timothy Lynch, Hilton McDavid and Noel M. Cowell, A Peter Hakim (with Kimberly Covington), Perspective on Cutting Edge Research for Crime and Craig Deare, AMB Adam Blackwell, and Security Policies and Programs in the Caribbean General (ret.) Barry McCaffrey Tyrone James, The Growth of the Private Security Industry in Barbados: A Case Study BOOK REVIEWS Phil Kelly, A Geopolitical Interpretation of Security Joseph Barron: Review of Max Boot, Concerns within United States–Latin American Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Relations Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present Emily Bushman: Review of Mark FOCUS ON BRAZIL Schuller, Killing With Kindness: Haiti, Myles Frechette and Frank Samolis, A Tentative International Aid, and NGOs Embrace: Brazil’s Foreign and Trade Relations with Philip Cofone: Review of Gastón Fornés the United States and Alan Butt Philip, The China–Latin Salvador Raza, Brazil’s Border Security Systems America Axis: Emerging Markets and the Initiative: A Transformative Endeavor in Force Future of Globalisation Design Cole Gibson: Review of Rory Carroll, Shênia K. de Lima, Estratégia Nacional de Defesa Comandante: -

Maggie Siff Still Enjoys Handling 'Billions'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! May 1 - 7, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 S L P E I F W P S L Z A R V E Your Key 2 x 3" ad C Y K O Q Q U E N D O R E C N U B V C H U C K W L W Y N K A To Buying R N O L E N R C U E S A V I N and Selling! M D L B A W Y L H W N X T W J 2 x 3.5" ad B U K I B B E X L I C R H E T A C L L V Y W N M S K O I K S W L A S U A B O D U T M S E O A E P T W U D S B Y E Y I S G U N U O H C A P I T A L F K N C E V L B E G A B V U P F A E R M W L V K R B W G R F O W F “Billions” begins its G I A M A T T I R I V A L R Y fifth season Sunday D E Z E B I F A N R J K L F E on Showtime. -

Tricks of the Light

Tricks of the Light: A Study of the Cinematographic Style of the Émigré Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan Submitted by Tomas Rhys Williams to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film In October 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to explore the overlooked technical role of cinematography, by discussing its artistic effects. I intend to examine the career of a single cinematographer, in order to demonstrate whether a dinstinctive cinematographic style may be defined. The task of this thesis is therefore to define that cinematographer’s style and trace its development across the course of a career. The subject that I shall employ in order to achieve this is the émigré cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, who is perhaps most famous for his invention ‘The Schüfftan Process’ in the 1920s, but who subsequently had a 40 year career acting as a cinematographer. During this time Schüfftan worked throughout Europe and America, shooting films that included Menschen am Sonntag (Robert Siodmak et al, 1929), Le Quai des brumes (Marcel Carné, 1938), Hitler’s Madman (Douglas Sirk, 1942), Les Yeux sans visage (Georges Franju, 1959) and The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961). -

The Domestic Terrorist Threat: Background and Issues for Congress

The Domestic Terrorist Threat: Background and Issues for Congress Jerome P. Bjelopera Specialist in Organized Crime and Terrorism January 17, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42536 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Domestic Terrorist Threat: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The emphasis of counterterrorism policy in the United States since Al Qaeda’s attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11) has been on jihadist terrorism. However, in the last decade, domestic terrorists—people who commit crimes within the homeland and draw inspiration from U.S.-based extremist ideologies and movements—have killed American citizens and damaged property across the country. Not all of these criminals have been prosecuted under terrorism statutes. This latter point is not meant to imply that domestic terrorists should be taken any less seriously than other terrorists. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) do not officially list domestic terrorist organizations, but they have openly delineated domestic terrorist “threats.” These include individuals who commit crimes in the name of ideologies supporting animal rights, environmental rights, anarchism, white supremacy, anti-government ideals, black separatism, and anti-abortion beliefs. The boundary between constitutionally protected legitimate protest and domestic terrorist activity has received public attention. This boundary is especially highlighted by a number of criminal cases involving supporters of animal rights—one area in which specific legislation related to domestic terrorism has been crafted. The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (P.L. 109-374) expands the federal government’s legal authority to combat animal rights extremists who engage in criminal activity. -

The Dial 1929

'O^W-s4^ 3RMyu ^ V LIBRARY ^ s ^VGHAM^ STATE NORMAL SCHOOL FRAMINGHAM MASSACHUSETTS —— — PROLOGUE "The golden opportunity Is never offer'd twice, seize then the hour When fortune smiles and duty points the way; Nor shrink aside to 'scape the spectre Fear, Nor pause though pleasure beckon from her bower But bravely bear thee onward to the goal." OLD PLAY. 370-7 11*1 I M"S/cv i DEDICATION The Class of 1929 affectionately si£ dedicates the Dial am (Si I to I 1 their good friend and teacher I Corinne E. Hall i3 whose interest and spirit I has made us realize the worth of i i Our Chosen Profession. WHITTEMOR13 LIBRARY Fra; -ge Framingham, Massachusetts MISS CORINNE E. HALL To the Class of 1929 "'The finest things of life can seldom be meas- ured by a tape line or weighed by a pair of scales. Xo scientist can determine how much is added to human happiness by the fragrance of a rose, the beauty of a sunset or the glory of the stars. In like manner poets and painters have exhausted their talents in trying to portray the meaning of home. The elements that enter into its make-up are of such stuff as dreams are made of for home is a matter of feeling, not reasoning. It is the place where one belongs, where one fits in, where one has a right to be because in a peculiar sense it is one's - own. ' QUOTED FROM DEAN RUSSELL. BY MISS HALL. JAMES CHALMERS, A.B., Ph.D., D.D., L.L.D., Principal ' *l£o (..V^ I have selected as most appropriate to your clientele, Chaucer's description of the Oxford student. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

SATURDAY EVENING JULY 24, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Magnum P.I

SATURDAY EVENING JULY 24, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Magnum P.I. ’ 48 Hours ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Paid Prog. NCIS “Hail & Farewell” NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 2020 Tokyo Olympics Beach Volleyball, Gymnastics, 3x3 Basketball, Swimming. (N) News 2020 Tokyo Olympics Olympics 5 52020 Tokyo Olympics Beach Volleyball, Gymnastics, 3x3 Basketball, Swimming. (N) News 2020 Tokyo Olympics Olympics 6 6Hell’s Kitchen ’ LEGO Masters ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Funniest Home Videos Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle “Sleeper” ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Toronto FC at Chicago Fire FC. (N) Weekend News WGN News Potash Two Men Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Father Brown ’ Frankie Drake Death in Paradise ’ Austin City Limits ’ Doctor Who “City of Death” Burt Wolf Father 11 Father Brown ’ Death in Paradise ’ Shakespeare Professor T ’ Unforgotten Downton Abbey on Masterpiece ’ 12 12 Funniest Home Videos Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Smile 24 24 Heartland ’ Murdoch Mysteries ’ Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Hell’s Kitchen ’ LEGO Masters ’ News Rookies Game of Talents ’ Bensinger Raw Travel Whacked Smile Paid Prog.