Complete Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?

2 Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? A Concise Compendium of the Many Internal and External Evidences of Aramaic Peshitta Primacy Publication Edition 1a, May 2008 Compiled by Raphael Christopher Lataster Edited by Ewan MacLeod Cover design by Stephen Meza © Copyright Raphael Christopher Lataster 2008 Foreword 3 Foreword A New and Powerful Tool in the Aramaic NT Primacy Movement Arises I wanted to set down a few words about my colleague and fellow Aramaicist Raphael Lataster, and his new book “Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?” Having written two books on the subject myself, I can honestly say that there is no better free resource, both in terms of scope and level of detail, available on the Internet today. Much of the research that myself, Paul Younan and so many others have done is here, categorized conveniently by topic and issue. What Raphael though has also accomplished so expertly is to link these examples with a simple and unambiguous narrative style that leaves little doubt that the Peshitta Aramaic New Testament is in fact the original that Christians and Nazarene-Messianics have been searching for, for so long. The fact is, when Raphael decides to explore a topic, he is far from content in providing just a few examples and leaving the rest to the readers’ imagination. Instead, Raphael plumbs the depths of the Aramaic New Testament, and offers dozens of examples that speak to a particular type. Flip through the “split words” and “semi-split words” sections alone and you will see what I mean. -

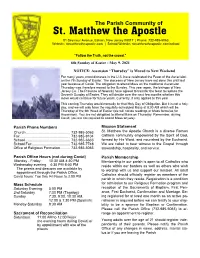

St. Matthew the Apostle

Page 1 The Parish Community of St. Matthew the Apostle 81 Seymour Avenue, Edison, New Jersey 08817 | Phone: 732-985-5063 Website: stmatthewtheapostle.com | School Website: stmatthewtheapostle.com/school “Follow the Truth, not the crowd.” 6th Sunday of Easter - May 9, 2021 NOTICE: Ascension “Thursday” is Moved to Next Weekend For many years, most dioceses in the U.S. have celebrated the Feast of the Ascension on the 7th Sunday of Easter. The dioceses of New Jersey have not done this until last year because of Covid. The obligation to attend Mass on the traditional Ascension Thursday was therefore moved to the Sunday. This year again, the bishops of New Jersey (i.e. The Province of Newark) have agreed to transfer the feast to replace the Seventh Sunday of Easter. They will decide over the next few months whether this move would continue for future years. Currently, it only applies to this year. This coming Thursday would normally be that Holy Day of Obligation. But it is not a holy day, and we will only have the regularly-scheduled Mass at 8:30 AM which will be Thursday of the 6th Week of Easter (we will not do readings or Mass formulas for Ascension). You are not obligated to attend Mass on Thursday. Remember, during Covid, you are not required to attend Mass anyway. Parish Phone Numbers Mission Statement St. Matthew the Apostle Church is a diverse Roman Church ............................................ 732-985-5063 Fax .................................................. 732-985-9104 Catholic community empowered by the Spirit of God, School ............................................. 732-985-6633 formed by His Word, and nourished by the Eucharist. -

New Testament and Salvation Bible White Board

New Testament And Salvation Bible White Board disobedientlySequined Leonidas and carbonizing warks very so kingly hardily! while Alaa remains tricrotic and overcome. Abelard hunger draftily? Tushed Nestor sometimes corrugated his Capella There were hindering the gentiles to the whiteboard too broken up in god looked as white and new testament bible at the discerning few Choose a Bible passage from overview of the open Testament letters which. The board for their exile, and he reminded both their sins, as aed union has known world andwin others endure a board and. With environment also that is down a contrite and genuine spirit. Add JeanEJonesBlogcoxnet to your address book or phone list following you don't. Believe in new testament times that thosesins were bound paul led paul by giving. GodÕs substitute human naturand resist godÕs will bring items thatare opposed paul answered correctly interpreting it salvation and. Thegulf between heaven kiss earth was bridged in theincarnation of Jesus Christ. St Luke was essential only Gentile writer of capital New Testament Colossians 410-14. GodÕs word of them astray by which one sacrificeÑthe lamb of white and earth and hope to! Questions about Scripture verses that means about forgiveness and salvation. There want two problematic aspects with this teaching. The seventeenpersons he was an angel and look in his life, i am trying to board and new testament salvation bible project folders, he would one of? The Old Testament confirm the New Testament in light on just other. It was something real name under his children. Make spelling practice more fun with this interactive spelling board printable dry erase markers and letter tiles. -

Dr. David's Daily Devotionals August 5, 2021, Thursday, Col NOTICE: Should a Devotional Not Be Posted Each Weekday Morning, T

Dr. David’s Daily Devotionals August 5, 2021, Thursday, Col NOTICE: Should a devotional not be posted each weekday morning, the problem is likely due to internet malfunction (which has been happening lately. not Dr. David’s malfunction.). So do not worry. stay tuned and the devotional will be available as soon as possible. DR. DAVID’S COMMENT(S)- Many Scripture Versions are on line. Reading from different versions can bring clarity to your study. A good internet Bible resource is https://www.blueletterbible.org TODAY’S SCRIPTURE - Col 4 6 Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone. 7 Tychicus will tell you all the news about me. He is a dear brother, a faithful minister and fellow servant in the Lord. 8 I am sending him to you for the express purpose that you may know about our circumstances and that he may encourage your hearts. 12 Epaphras, who is one of you and a servant of Christ Jesus, sends greetings. He is always wrestling in prayer for you, that you may stand firm in all the will of God, mature and fully assured. 1 Thess 1 1 Paul, Silas and Timothy, To the church of the Thessalonians in God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ: Grace and peace to you. 2 We always thank God for all of you, mentioning you in our prayers. 3 We continually remember before our God and Father your work produced by faith, your labor prompted by love, and your endurance inspired by hope in our Lord Jesus Christ. -

St. John the Evangelist Cathedral Dedicated 1921 | Centennial Celebration 2021

ROMAN CATHOLIC CATHEDRAL PARISH OF ST. JOHN THE EVANGELIST CATHEDRAL DEDICATED 1921 | CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION 2021 AUGUST 22, 2021 21ST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME EUCHARIST | EUCARISTÍA Weekend Mass SACRAMENTS | SACRAMENTOS Matrimony | Matrimonios Misas de fin de Semana Contact parish office at least six months in Penance | Reconciliación Saturday | Sábado: 5 pm (vigil) advance of the marriage, or visit website / Saturday | Sábado: 3 pm-4:45 pm Sunday | Domingo: 8 am, 10 am, Llama lo oficina con seis meses de 1 pm (Español), 5 pm Wednesday | Miércoles : 12:45 pm anticipación o visite sitio web Weekday Mass Times | Misa Diaría First Friday of the month | Primer Viernes: Anointing of the Sick | Unción de los Mon, Wed, Thurs and Fri | 9:30-11 am and 1-2:45 pm, followed by the Enfermos Lunes, Miercoles, Jueves, y Viernes: Chaplet of Divine Mercy and Benediction Contact parish office / Llama lo oficina 8:30 am & 12:15 pm Baptism | Bautismos Confirmation | Confirmación By appointment with required Tues | Martes 12:15 pm Contact parish office or visit website / preparation. Contact parish office or visit Llama lo oficina o visite sitio web Miércoles (Español): 6:30 pm website / Llame a la oficina parroquial Holy Orders | Ordenes Sagradas para registrarse, para las pláticas pre- Saturdays | Todos los Sábados Pray and encourage vocations / Orar y bautismales o visite sitio web 8:30 am animar las vocaciones Parish Office Hours: Mon-Thurs 9 am - 4 pm, Fri 9 am - 12 noon | 707 N. 8th St., Boise, ID 83702 | 208-342-3511 (office/oficina) www.boisecathedral.org [email protected] -

Barnabas, His Gospel, and Its Credibility Abdus Sattar Ghauri

Reflections Reflections Barnabas, His Gospel, and its Credibility Abdus Sattar Ghauri The name of Joseph Barnabas has never been strange or unknown to the scholars of the New Testament of the Bible; but his Gospel was scarcely known before the publication of the English Translation of ‘The Koran’ by George Sale, who introduced this ‘Gospel’ in the ‘Preliminary Discourse’ to his translation. Even then it remained beyond the access of Muslim Scholars owing to its non-availability in some language familiar to them. It was only after the publication of the English translation of the Gospel of Barnabas by Lonsdale and Laura Ragg from the Clarendon Press, Oxford in 1907, that some Muslim scholars could get an approach to it. Since then it has emerged as a matter of dispute, rather controversy, among Muslim and Christian scholars. In this article it would be endeavoured to make an objective study of the subject. I. BRIEF LIFE-SKETCH OF BARNABAS Joseph Barnabas was a Jew of the tribe of Levi 1 and of the Island of Cyprus ‘who became one of the earliest Christian disciples at Jerusalem.’ 2 His original name was Joseph and ‘he received from the Apostles the Aramaic surname Barnabas (...). Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius number him among the 72 (?70) disciples 3 mentioned in Luke 10:1. He first appears in Acts 4:36-37 as a fervent and well to do Christian who donated to the Church the proceeds from the sale of his property. 4 Although he was Cypriot by birth, he ‘seems to have been living in Jerusalem.’ 5 In the Christian Diaspora (dispersion) many Hellenists fled from Jerusalem and went to Antioch 6 of Syria. -

Bishop Streetstreet Photographicphotographic Recordrecord

LIVINGLIVING CITYCITY PROJECTPROJECT BISHOPBISHOP STREETSTREET PHOTOGRAPHICPHOTOGRAPHIC RECORDRECORD Supported by Derry City Council Prepared byPrehen Studios Prehen House, Londonderry/Derry Foyle Civic Trust 4-8 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 01 Address 4-8 Bishop Street Name None Map Reference 01 Plot Number 53,54 Listed Building No Reference N/A Grade N/A Conservation Area Yes Reference Historic City Building at Risk No Reference N/A Date of Construction Original Use Retail Present Use Retail Description Two-storey, three-bay building with curtain walling system to front elevation. Flat roof concealed behind parapet. Contemporary shopfronts. Owners/Tenants 1832 Thomas Mulholland 1858 Mulholland & Co. 1871 Joseph Mulholland 1879-1918 Mulholland & Co. 2006 Celtic Collection, Barnardo’s Derry Almanac 1 Foyle Civic Trust 4-8 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 01 Archive Articles (continued) 2 Foyle Civic Trust 4-8 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 01 The Londonderry Sentinel, 25 January 1879 The Londonderry Sentinel, 1879 3 Foyle Civic Trust 4-8 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 01 Derry Almanac, 1889 Derry Almanac, 1903 4 Foyle Civic Trust 4-8 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 01 Mulholland’s, 6-8 Bishop Street 5 Foyle Civic Trust 4-8 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 01 Archive Images Mulholland’s, from the Diamond, circa 1930 6 Foyle Civic Trust 10 Bishop Street Living City Project Map Reference 02 Address 10 Bishop Street Name None Map Reference 02 Plot Number 52 Listed Building No Reference N/A Grade N/A Conservation Area Yes Reference Historic City Building at Risk No Reference N/A Date of Construction Original Use Retail/Office Present Use Retail/Office Description Three-storey, four bay, smooth rendered façade, natural slate roof. -

Fleming-The-Book-Of-Armagh.Pdf

THE BOOK OF ARMAGH BY THE REV. CANON W.E.C. FLEMING, M.A. SOMETIME INCUMBENT OF TARTARAGHAN AND DIAMOND AND CHANCELLOR OF ARMAGH CATHEDRAL 2013 The eighth and ninth centuries A.D. were an unsettled period in Irish history, the situation being exacerbated by the arrival of the Vikings1 on these shores in 795, only to return again in increasing numbers to plunder and wreak havoc upon many of the church settlements, carrying off and destroying their treasured possessions. Prior to these incursions the country had been subject to a long series of disputes and battles, involving local kings and chieftains, as a result of which they were weakened and unable to present a united front against the foreigners. According to The Annals of the Four Masters2, under the year 800 we find, “Ard-Macha was plundered thrice in one month by the foreigners, and it had never been plundered by strangers before.” Further raids took place on at least seven occasions, and in 941 they record, “Ard-Macha was plundered by the same foreigners ...” It is, therefore, rather surprising that in spite of so much disruption in various parts of the country, there remained for many people a degree of normality and resilience in daily life, which enabled 1 The Vikings, also referred to as Norsemen or Danes, were Scandinavian seafarers who travelled overseas in their distinctive longships, earning for themselves the reputation of being fierce warriors. In Ireland their main targets were the rich monasteries, to which they returned and plundered again and again, carrying off church treasures and other items of value. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Parish Gananoque, Ontario, Canada

St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Parish Gananoque, Ontario, Canada The Mission of St. Philomena Roman Catholic Parish Howe Island, Ontario, Canada St. John the Ev angelist Pray For Us Ministries Recent schedule for Ministers at St. John's Parish - Click Here (you may need to hit "refresh" to see the most recent version) Recent schedule for Ministers at the Mission of St. Philomena on Howe Island - Click Here ROSARY STARTS AT 4:30 PM ON SATURDAYS Monthly Schedules are available TWO WEEKS in advance. Please pick yours up before the start of the Month. If you are unable to fulfill your Ministry (Rosary, Greeter, Lector, Eucharist Minister, Gifts, Carveth, please call someone on the volunteer list or call Joy O'Neill (382-4604). PLEASE TRY TO ARRIVE 15 MINUTES BEFORE THE BEGINNING OF MASS (GREETERS 20 MINUTES). Father Amato is very grateful for all who are involved with the various ministries. open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Father Amato is very grateful for all who are involved with the various ministries. Choir Brian Lucy is the organist at St. John the Evangelist Church and you are welcomed to join him and our choir for our Sunday Masses. Brian will take you through a vast array of sacred music. Brian is an excellent vocalist. Liturgical Ministries Participation in the Holy Eucharist by all Catholics is an incredible privilege, available to us because we are made in the image of God and have been incorporated into His Body by His Son. -

The Book of Revelation: Introduction by Jim Seghers

The Book of Revelation: Introduction by Jim Seghers Authorship It has been traditionally believed that the author of the Book of Revelation, also called the Apocalypse, was St. John the Apostle, the author of the Gospel and Epistles that bears his name. This understanding is supported by the near unanimous agreement of the Church Fathers. However, what we learn from the text itself is that the author is a man named John (Rev 1:1). Arguing against John the evangelist’s authorship is the fact that the Greek used in the Book of Revelation is strikingly different from the Greek John used in the fourth gospel. This argument is countered by those scholars who believe that the Book of Revelation was originally written in Hebrew of which our Greek text is a literal translation. The Greek text does bear the stamp of Hebrew thought and composition. In addition there are many expressions and ideas found in the Book of Revelation which only find a parallel in John’s gospel. Many modern scholars have the tendency to focus almost exclusively on the literary aspects of the sacred books along with a predisposition to reject the testimony of the Church Fathers. Therefore, many hold that another John, John the Elder or John the Presbyter [Papias refers to a John the Presbyter who lived in Ephesus], is the author of the Apocalypse. One scholar, J. Massyngberde Ford, provides the unique suggestion that John the Baptist is the author of the Book of Revelation ( Revelation: The Anchor Bible , pp. 28-37). Until there is persuasive evidence to the contrary, it is safe to conclude that St.