Discovering an International Language Called Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time for Europe to Pace Development of SPV Page 2 |No

Mehr Vision|No.12|November-December 2018 Time for Europe to pace development of SPV Page 2 |No. 12|Nov - Dec 2018 MEHR NEWSAGENCY Contents Muslims need to talk more with each other: Bajrami 4 Iran is a role model for uniting Muslim states: Indonesian scholar 5 Imam Khomeini initiated idea of Islamic Unity: Prof. Mirza 6 Only Resistance can solve Palestinian crisis: German analyst 7 Dossier Palestine a big umbrella that gathers all Muslims: Hamas rep. 8 Theorizing religion in intl. relations not only feasible but essential 10 PGCC never was effective organization: Shireen Hunter 12 Qatar withdrawal from OPEC may increase Iran’s production shar 13 Political squabbles among OPEC members have weakened its efficacy 14 US new sanctions to impact Iranian nation: Dorsey 16 Al-Khalifa regime threatened people to vote in elections: Bahraini cleric 17 Interview EU army won’t threaten NATO future: ex-CIA official 18 US had no choice but to grant Iranian oil buyers waivers 19 Mehr Vision The sad fate of Europe’s leading figure 22 Tel Aviv’s ‘northern shield’ operation’s objective in Lebanon border 23 Managing Director: Ali Asgari FATF member countries, the very center of money laundering 24 Editorial Board: West return to 2007: Europe’s anger over incompetent politicians 25 Seyed Amir Hassan Dehghani, Will Clinton have the EU’s support? 26 Mohammad Ghaderi, France’s unrestful days with Macron 27 Payman Yazdani Opinion US propaganda war against Iran doomed to failure 28 Editorial Coordinator: Kornet missile wins over Netanyahu’s cabinet 29 Lachin Rezaian Democrats vs. -

Ars Choralis 2018

HrVATSKA UDrUGA ZBoroVo\A CroATIAN CHorAL DIrECTorS ASSoCIATIoN mE\UNAroDNI ZBorSKI INSTITUT INTErNATIoNAL CHorAL INSTITUTE ARS CHORALIS 2018 Peti međunarodni simpozij o korusologiji zborska umjetnost – pjevanje – glas The Fifth International Symposium on Chorusology Choral Art – Singing – Voice Zagreb, 5. – 7. 4. 2018 CroATIA ARS CHORALIS 2018 Peti međunarodni simpozij o korusologiji zborska umjetnost – pjevanje – glas The Fifth International Symposium on Chorusology choral art – singing – voice Organizator / Organizer Hrvatska udruga zborovođa / Croatian Choral Directors Association Međunarodni zborski institut / International Choral Institute www.huz.hr • www.choralcroatia.com Ovaj je simpozij posvećen / This Symposium is dedicated to April 16th WORLD VOICE DAY SVJETSKI DAN GLASA 16. travnja world-voice-day.org Počasni gost / Guest of Honour Dr. CHUN KOO – South Korea Ovaj je simpozij posvećen / This Symposium is dedicated to Ovaj je simpozij organiziran od The Symposium is organized by Hrvatske udruge zborovođa The Croatian Choral DIrectors Association u suradnji s in collaboration with Institutom za crkvenu glazbu The Institute for Church Music Katoličkoga bogoslovnog fakulteta of Catholic Theological Faculty of Sveučilišta u Zagrebu University of Zagreb Simpozij je sufinanciran od The symposium is financialy supported by Ministarstva kulture Republike Hrvatske The Ministry of Culture Turističke zajednice grada Zagreba The Zagreb Tourist Board Medijski pokrovitelj Hrvatski katolički radio / Croatian Catholic Radio Tematska područja -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Nohe Khan’ the Creator of Glory, the Creator of the World, the Creator of Fortune, the One Who Sends the Prophets

Alexander RAhbARi My Mother Persia Symphonic Poems • 3 Nos. 9 and 10 Ladislav Fančovič, Saxophone Reza Fekri, Tenor Prague Metropolitan Orchestra Alexander Rahbari Alexander Rahbari (b. 1948) My Mother Persia – Symphonic Poems Nos. 9 and 10 Alexander Rahbari was born in Tehran, Iran. He studied began writing the most lauded pieces of his career. His Symphonic Poem No. 10 ‘Morshed’ violin and composition with Rahmatollah Badiee and works include Persian Mysticism – A Symphonic Poem for Dedicated to Ahmad Pejman Hossein Dehlavi at the Persian National Music Orchestra (1968), music used in United Nation advertising Conservatory. From the age of 17, he was a violinist at performed by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (1975), the Nowadays, a ‘Morshed’ is a person who has a good singing from the Shahnameh (‘The Book of Kings’), written by the the Fine Arts Administration Orchestra under the baton of soundtrack for a documentary by French director André voice and sits in their special place (named a ‘dam’), Persian poet Ferdowsi. In the past, the Morshed was the Hossein Dehlavi. Soon after receiving his violin diploma Malraux (1977), Beirut Symphonic Poem (1985) originally playing and singing during the pahlevani and zoorkhaneh person who trained the athletes. During the rituals, the from the National Conservatory, he won a scholarship written for nine flutes, Halfmoon (1984), a piece for rituals (the UNESCO-designated name for varzesh-e Morshed wears a piece of cloth on his shoulder named from the Iran Ministry of Culture and Art to study orchestra and choir performed and commissioned by the pahlavāni , or ‘ancient sport’). -

Iran to Construct 540MW Power Plant in Syria Resolving Qatar Crisis Is Not

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 20,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13221 Wednesday OCTOBER 3, 2018 Mehr 11, 1397 Muharram 23, 1440 Amano rejects We took you seriously, Iran’s Persepolis earn Iran sends four Netanyahu claims Shamkhani tells Bolton remarkable win over submissions to Asia Pacific about Iran 2 after missile attack 2 Al Sadd in ACL semis 15 Screen Awards 16 Iran to construct 540MW See page 4 power plant in Syria ECONOMY TEHRAN – Iranian Aliabadi on the sidelines of a meeting between deskMapna Group Compa- Iran’s Minister of Energy Reza Ardakanian Rial recovers ny signed a memorandum of understanding and Syrian Minister of Electricity Moham- (MOU) with Syrian Public Establishment mad Zuheir Kharboutli in Tehran. of Electricity for Generation (PEEG) on Based on the MOU, the €411-million project Tuesday for constructing a 540 megawatt will start in the beginning of 2019. The first (MW) combined cycle power plant in Syr- gas unit of the power plant is expected to be ian port city of Latakia, IRNA reported. completed in 15 months and the second one The MOU was signed by PEEG’s Man- will be built in two years.The power plant’s aging Director Mahmoud Ramadan and feedstock will be supplied from Syria’s gas unexpectedly MAPNA Group’s Managing Director Abbas fields through a 70-kilometer pipeline. Guardian: Saudi funds TV that gave airtime to Ahvaz attack supporter ‘A source close to Saudi crown prince says Following is the text of the report head- Iran International’s money come from -

CV 2020.Pages

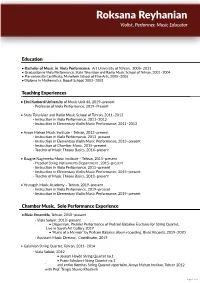

Roksana Reyhanian Violist, Performer, Music Educator Education • Bachelor of Music in Viola Performance, Art University of Tehran, 2006–2011 • Graduation in Viola Performance, State Television and Radio Music School of Tehran, 2001–2004 • Pre-university Certificate, Mahdiyeh School of Fine Arts, 2005–2006 • Diploma in Mathematics, Booali School, 2002–2005 Teaching Experiences • Elmi Karbordi University of Music Unit 46, 2019–present - Professor of Viola Performance, 2019–Present • State Television and Radio Music School of Tehran, 2011–2013 - Instruction in Viola Performance, 2011–2013 - Instruction in Elementary Violin Music Performance, 2011–2013 • Avaye Mahan Music Institute – Tehran, 2013–present - Instruction in Viola Performance, 2013–present - Instruction in Elementary Violin Music Performance, 2013–present - Instruction of Chamber Music, 2015–present - Teacher of Music Theory Basics, 2014–present • Baaghe Naghmeha Music Institute – Tehran, 2015–present - Head of String Instruments Department , 2015–present - Instruction in Viola Performance, 2015–present - Instruction in Elementary Violin Music Performance, 2015–present - Teacher of Music Theory Basics, 2018–present • Yasnagah Music Academy – Tehran, 2019–present - Instruction in Viola Performance, 2019–present - Instruction in Elementary Violin Music Performance, 2019–present Chamber Music, Solo Performance Experience • Bivác Ensemble, Tehran, 2018–present - Viola Soloist, 2018–present • Dispersion, Premier Performance of Pedram Babaiee Fractions for String Quartet, Live in Sayeh Art Gallery 2019 • “Ruins of a Memoir” by Pedram Babaiee album recording, Bivác Records, 2019–2020 - Assistant Music Director, Coordinator, 2019 • Galamian String Quartet, Tehran, 2011–2014 - Viola Soloist, 2012 • Joseph Haydn String Quartet no.1 • Franz Schubert String Quartet no.1 ` and entire Komitas String Quartet repertoire, Avaye Mahan Institue, Tehran 2012 with Prof. -

Comparative Ontology and Iranian Classical Music

COMPARATIVE ONTOLOGY AND IRANIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC ________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________________ by Erum Naqvi July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Philip Alperson, Advisory Chair, Department of Philosophy Susan Feagin, Committee Member, Department of Philosophy Espen Hammer, Committee Member, Department of Philosophy Lara Ostaric, Committee Member, Department of Philosophy Lydia Goehr, External Member, Columbia University © Copyright 2015 by Erum Naqvi All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT My project began quite innocently, when, in my first philosophy of music class as a graduate student, I found it extraordinarily difficult to bring questions about the nature and meaning of music to bear on the case of Iranian classical music. I knew very little, technically speaking, about Iranian classical music at the time, but what I did know was challenging to reconcile with many commonplace assumptions about music in philosophy. Specifically, that this tradition is highly performative, that musicians rarely use scores, and, importantly, that anyone who calls herself a musician but cannot extemporize, is not really considered much of a musician in Iran at all. This, I remember all too vividly from my teenage years, when I recall the bemused -

Rockets Fired at Occupied Lands

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 20,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13253 Tuesday NOVEMBER 13, 2018 Aban 22, 1397 Rabi’ Al awwal 5, 1440 Larijani urges Saudis close to Bin Mohammadi named Martyna Kosecka to conduct Europeans to act more Salman tried to kill Iran’s freestyle Poland’s independence independently 2 Iranian officials 2 wrestling coach 15 concert in Tehran 16 ‘EU to continue transport co-op See page 13 with Iran despite sanctions’ ECONOMY TEHRAN — Euro- in Tehran, Maja Bakran Marcich said “the Rockets desk pean Commission’s EU will continue to cooperate with Iran deputy director-general for mobility and in the framework of agreements signed in transport said EU is going to continue its various fields of transportation.” transport cooperation with Iran despite The official noted that 80 percent of U.S. sanctions, IRNA reported on Monday. the world’s trade is conducted through Speaking in a two-day workshop on sea transport and since a big chunk of fired at ports, maritime and logistics held by Iran’s this trade is between Asia and Europe, Ports and Maritime Organization (PMO) it cannot be stopped under any circum- in collaboration with the European Union stances. 4 occupied UNWTO chief sees Iran as a safe, peaceful destination TOURISM TEHRAN — The vis- stated, Tasnim reported. deskiting United Nations He made the remarks in a press conference World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) followed by the opening ceremony of the 40th lands secretary general on Monday said “We are UNWTO Affiliate Members Plenary Session, willing to introduce Iran to the world as which opened in the city of Hamedan. -

3Rd-TCMF-Booklet.Pdf

فســتیوال موســیقی معاصــر تهــران بــه عنــوان تنهــا فســتیوال ملــی و بینالمللی در حــوزه موســیقی معاصــر و آکادمیــک، یــک رویــداد فرهنگی و هنری مســتقل اســت کــه بــا حمایــت و همــکاری نهادهــا و انجمــن هــای فرهنگــی و هنــری بصــورت ســاﻻنه برگــزار مــی شــود. طــرح اولیــه برگــزاری ایــن فســتیوال توســط نویــد گوهــری )مدیــر هنــری( و احســان تــارخ )مدیــر اجرایــی( در بهــار 1393 نوشــته شــد و در تابســتان 1394 بــا همفکــری و برنامــه ریــزی دکتــر حســین ســروی )مشــاور امــور بیــن الملــل و نظــارت راهبــردی( و بــا همیــاری و حمایــت دفتــر موســیقی وزارت فرهنــگ و ارشــاد اســامی، بنیــاد رودکــی، مــوزه هنرهــای معاصــر تهــران اولیــن اقدامــات اجرایــی آن صــورت گرفــت. همزمــان بــا تاســیس کانــون موســیقی در مــوزه هنرهــای معاصــر تهــران، ایــده برگــزاری فســتیوال بیــن المللی موســیقی معاصر تهــران توســط ایــن کانــون پیگیــری شــد. در پاییــز 1394 شــورای علمــی و هنــری فســتیوال بــا همــکاری دکتــر حمیدرضا اردﻻن )مشــاور علمــی(، آیدین صمیمی مفخم، مارتینا کوسســکا )مشــاوران هنری( تشــکیل گردید و اقدامات عملی جهــت برگــزاری نخســتین دوره فســتیوال بیــن المللــی موســیقی معاصــر تهــران بــا اعــام فراخــوان و دعــوت از گــروه هــای خارجی با همکاری موسســه موســیقی نویــن اســپکترو بــه انجــام رســید. در نخستین دوره فستیوال بین المللی موسیقی معاصر تهران که اردیبهشت مــاه 1395 برگــزار شــد، 116 هنرمنــد ایرانــی و خارجــی در قالــب 21 گــروه موســیقی از کشــورهای ایــران، بلژیــک، ســوئد، گرجســتان، ســوییس، رومانــی و لهســتان بــه اجرای برنامه پرداختند و 20 ســخنران از کشــورهای ایران، لهســتان، گرجســتان، هلنــد و آلمــان مقــاﻻت خــود را در بخــش ســمینارها ارائــه نمودنــد. همچنیــن در ایــن دوره آثــاری از 77 آهنگســاز معاصــر ایرانــی و بیــن المللــی اجــرا گردیــد کــه 27 اثــر بــرای نخســتین بــار در جهــان )world Premiere( اجــرا شــد. -

Analysis of Iranian Film Music (With Focus on Some Contemporary Composers)

Université de Montréal Analyse de la Musique de Film Iranien (Avec un accent sur certains compositeurs contemporains) Analysis of Iranian Film Music (With focus on some contemporary composers) Présenté par Sharareh Sheikhkhan Unité académique : Faculté de Musique Mémoire présenté en vue de l'obtention du grade de Maîtrise - Musique en Composition pour l'écran August 30th, 2020 © Sharareh Sheikhkhan, 2020 Université de Montréal Unité académique : Faculté de Musique Ce mémoire intitule Analyse de la Musique de Film Iranien (Avec un accent sur certains compositeurs contemporains) Analysis of Iranian Film Music (With focus on some contemporary composers) Présenté par Sharareh Sheikhkhan Ce mémoire a été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Isabelle Panneton Président-rapporteur François-Xavier Dupas Directeur de recherche Pierre Adenot Membre du jury Research paper 2nd cycle (Master) University year 2019-2020 Analysis of Iranian film music (with focus on some contemporary composers) SHARAREH SHEIKHKHAN Principal discipline: InMICS Principal discipline teacher: François-Xavier Dupas, Dominique Pauwels Name of referent teacher: Stoffel Debuysere Name of methodology assistant : Martin Barnier Date of the presentation: October, 2020 Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my special thanks to my Principal discipline teacher Dr. Stoffel Debuysere for his patience, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me in all the time for research and writing this thesis. Second, I pay my deep sense of gratitude to my composition professor Dr. François- Xavier Dupas for all he did for me during this master’s degree. Without his continuous encouragement, support and enthusiasm, this study would hardly have been completed. I consider myself fortunate indeed to have had the opportunity to be his student. -

Recent Experimental Electronic Music Practices in Iran

Recent Experimental Electronic Music Practices in Iran: An Ethnographic and Sound-Based Investigation by Hadi Bastani A thesis submitted to Queen’s University Belfast in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sonic Arts Research Centre Queen’s University Belfast 2019 Supervisory Team Dr Simon Waters Dr Ioannis Tsioulakis ii Je ne dis […] pas les choses parce que je les penses, je les dis plutôt dans une fin d’auto- destruction pour ne plus les penser.1 Michel Foucault – Interview with Fons Elders (1971) 1 The quote is extracted from an interview published on YouTube on March 2014 titled Foucault – The Lost Interview, which was initially produced by the Dutch Philosopher Fons Elders for the Dutch Television in 13 September 1971, ahead of the famous debate between Foucault and Noam Chomsky, which took place in No- vember of the same year. The interview is accessible via the following link (last accessed 26 Jun. 2019). See 15:13–15:21 for the above quote: youtube.com/watch?v=qzoOhhh4aJg The whole interview is available in the form of a book titled "Freedom and Knowledge." It includes an introduction by Lynne Huffer and additional contributions by Fons Elders. It can be accessed via Vons Elders’ own webstie via the following link (last accessed 26 Jun. 2019): hfonselders.eu/product/m-f-free- dom-and-knowledge/ An excerpt is available for free online here (last accessed 26 Jun. 2019): academia.edu/6482878/Free- dom_and_Knowledge_book_extract_YouTube_clip_of_lost_Michel_Foucault_interview_pub- lished_forty_years_after_its_time_ iii iv Abstract The aim of this thesis is to identify and locate an experimental electronic music ‘scene’ in Iran within a web of historical-social-political-religious- economic-technological agencies. -

Persian Musicians Directory

Version 9.0 Dec. 2015 PERSIAN MUSICIANS DIRECTORY A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA Abbas Nia [Muhammad] traditional Dosazeh ( twin reed pipe) player of the khorasani repertoire (Kashmar) in the 1990’s. Abaei [Reza] Gheychak player. Cooperated with Payvar ensemble, Davod Varzideh (ney) and Mohammad Delnavazi (barbat),. Abdollahi “Sangdehi” [Parviz] Sorna, qarneh player from Mazandaran. Revivalist of Qarneh pipe with Lotfollah Seyfi. “ Date of Birth: 01 Persian date Farvardin 1354/1975. In 1364/1985, his father started the construction Laleva make additional Nmvd.dvrh with ust. Tibi spent on master tapes and music theory with Professor Ismaili came to a Lotfollah Seifi. Beloved, now led by the instrumental group and the group headed by Professor MohsenPour Shavash's activities. Shahrivar 79 (1999) First Prize as the top player of century-festival performers His numerous groups in the province and outside the province and work, including: Group Najma, Sama, Varesh, eager faith, Taraneh, Mah Teti, Roja, traditional Varshan, Shavash group that is a member for 8 years and has continued his association with other groups. For 8 years of playing in groups of Teti, Khojier, Shvash, Ouya, Najma, Varesh, Teti Jar, Mahal Roja, Taraneh, , Kordu Shahu traditional Varshan and research group Samaei Alborz activity and continued some of the works of three Czech, …” (Mehrava.com) Abidini [Hosein] traditional singer of the khorasani repertoire (Kashmar, Torbat e heidriyeh). Cooperated with dotar player Hosein Hadidian (dotar). Abshuri [Ali] traditional Sorna shawm player, kurdish –Kurmanji repertoire of the kurdish from North Khorasan in the 1990’s .