Redefining the Vernacular in the Hybrid Architecture of Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUILDING CONSTRUCTION NOTES.Pdf

10/21/2014 BUILDING CONSTRUCTION RIO HONDO TRUCK ACADEMY Why do firefighters need to know about Building Construction???? We must understand Building Construction to help us understand the behavior of buildings under fire conditions. Having a fundamental knowledge of buildings is an essential component of the decisiondecision--makingmaking process in successful fireground operations. We have to realize that newer construction methods are not in harmony with fire suppression operations. According to NFPA 1001: Standard for FireFighter Professional Qualifications Firefighter 1 Level ––BasicBasic Construction of doors, windows, and walls and the operation of doors, windows, and locks ––IndicatorsIndicators of potential collapse or roof failure ––EffectsEffects of construction type and elapsed time under fire conditions on structural integrity 1 10/21/2014 NFPA 1001 Firefighter 2 Level ––DangerousDangerous building conditions created by fire and suppression activities ––IndicatorsIndicators of building collapse ––EffectsEffects of fire and suppression activities on wood, masonry, cast iron, steel, reinforced concrete, gypsum wallboard, glass and plaster on lath Money, Money, Money….. Everything comes down to MONEY, including building construction. As John Mittendorf says “ Although certain types of building construction are currently popular with architects, modern practices will be inevitably be replaced by newer, more efficient, more costcost--effectiveeffective methods ”” Considerations include: ––CostCost of Labor ––EquipmentEquipment -

Gable Shed Building Guide by John Shank, Owner of Shedking, LLC 2016

Shedking's Gable Shed Building Guide by John Shank, owner of shedking, LLC 2016 This shed building guide should be used in conjunction with the gable shed plans available at my website shedking.net . These sheds can be used to build storage sheds, chicken coops, playhouses, tiny houses, garden sheds and much more! I have tried to make this guide as simple as possible, and I have tried to make my building plans as comprehensive and easy as possible to follow and understand. If at any time anything presented in the plans or building guide is not clear to you please contact me at [email protected]. As I always advise, please get a building permit and have your plans inspected and gone over by your local building inspector. Many counties in the United States do not require a permit for structures under a certain square footage, but it is still very wise to get the advise of your local building department no matter what the size of the structure. Email: [email protected] 1 Copyright 2016shedking.net If after purchasing a set of my plans and you want to know if they are good for your county, I won't be able to answer that question! All my plans are written utilizing standard building practices, but I cannot write my plans so that they satisfy every local building code. Safety is and should be your number one concern when building any outdoor structure. Table of Contents Disclaimer....................................................................................................................3 Wooden Shed Floor Construction.....................................................................................4 -

To Search High and Low: Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and China's

Scapegoat Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy Issue 03 Realism 30 To Search High and Low: Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and China’s Architectural Historiography, 1932–1946 by Zhu Tao MISSING COMPONENTS Living in the remote countryside of Southwest Liang and Lin’s historiographical construction China, they had to cope with the severe lack of was problematic in two respects. First, they were financial support and access to transportation. so eager to portray China’s traditional architec- Also, there were very few buildings constructed ture as one singular system, as important as the in accordance with the royal standard. Liang and Greek, Roman and Gothic were in the West, that his colleagues had no other choice but to closely they highly generalized the concept of Chinese study the humble buildings in which they resided, architecture. In their account, only one dominant or others nearby. For example, Liu Zhiping, an architectural style could best represent China’s assistant of Liang, measured the courtyard house “national style:” the official timber structure exem- he inhabited in Kunming. In 1944, he published a plified by the Northern Chinese royal palaces and thorough report in the Bulletin, which was the first Buddhist temples, especially the ones built during essay on China’s vernacular housing ever written the period from the Tang to Jin dynasties. As a by a member of the Society for Research in Chi- consequence of their idealization, the diversity of nese Architecture.6 Liu Dunzhen, director of the China’s architectural culture—the multiple con- Society’s Literature Study Department and one of struction systems and building types, and in par- Liang’s colleagues, measured his parents’ country- ticular, the vernacular buildings of different regions side home, “Liu Residence” in Hunan province, in and ethnic groups—was roundly dismissed. -

INSTITUTE of CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Hanover, NH 03755

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD_ AFFAIRS 23 Jalan AU5 C/3 Lembah Keramat Uln Kelang, Selangor Malaysia 20 September 1982 BEB-IO Groping Mr. Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Wheelock House West Wheelock Street Hanover, NH 03755 Dear Peter, Hijjas Kasturi is an architect. "For some time no," he says,"each of us has been try- ing in our various directions, to fiud Malaysian architec- ture. We haven't found it yet, and I think it will take at least another generation before anything is formalized. This is the beginning; a very exciting period, but one full of dis c ont inuit ies .-,' "we lack a charismatic leadership to define IVia!aysian architecture as Frank Lloyd Wright did at one time for Aer- ican architecture. We all come from diffe.rent architectural schools with different philosophies. There is no unity. Some architects only want to implement what they've learned abroad. Others think the inangkabau roof, 'Islaic' arches and other ornamentation are enough. Its a horrible misconception that these cons.titute Malaysian architecture. These are elements. Elements are superficial things. en you think in elements you will trap yourself and become artificial in your assess- ment and in your discipline. In my firm we are looking for semething deeper aan that. We are not always successful. But we are searching. We are groping. And we are very committed. I think one day we may make history." Heavy stuff coming from the founder and sole proprietor -of a seVenty-member architectural firm barely five years old this year, with most oi" its portfolio either on the drawing boards or under construction. -

The Borneo Bugle

The Borneo Bugle BORNEO PRISONERS OF WAR RELATIVES GROUP A MUTUAL GROUP TO HELP KEEP THE SPIRIT OF SANDAKAN ALIVE June 1st 2003 Volume 1, Issue 5 by Allan Cresswell PRESIDENT Anzac Day 2003 BOB BRACKENBURY TEL:(08)93641310 Anzac Day was commemorated in so many 5 ROOKWOOD ST MT PLEASANT WA 6153 different ways by various members in 2003. Dawn Services were being attended SECRETARY/TREASURER KEN JONES by our members at Kings Park, Irwin TEL:(08)94482415 10 CARNWRATH WAY Barracks and at the Sandakan Memorial DUNCRAIG WA 6023 EMAIL: [email protected] Park. Many of our members marched at the Perth Anzac Day March under our own LIAISON/RESEARCH/EDITOR ALLAN CRESSWELL banner whilst others attended Lynette TEL(08)94017574 153 WATERFORD DRIVE Silver’s morning service at Sandakan HILLARYS WA 6025 EMAIL: alcressy @iinet.net.au Memorial Park. COMMITTEE PERSON/EDITOR NON MESTON These two groups that visited North TEL(08)93648885 2 LEVERBURGH STREET Borneo were both travelling over much of ARDROSS WA 6153 EMAIL: [email protected] the Sandakan – Ranau Death March Route on Anzac Day and it was so fitting that In This Issue both groups had services and dedications enroute that day. Various written reports Anzac Day 2003 1 Tour Ladies with Candles at Passing of Carl Jensen 1/2 for most of these services are provided in Editorial 2 this issue of the Borneo Bugle by our Sandakan Memorial Park awaiting Commencement of ANZAC Day New Members 2 President on page 3, Ken Jones page 4/5 Coming Events 2 Dawn Service and Allan Cresswell page 6/7. -

Oscar Niemeyer's Mid-Twentieth-Century Residential Buildings

Challenging the Hierarchies of the City: Oscar Niemeyer’s Mid-Twentieth-Century Residential Buildings Challenging the Hierarchies of the City: Oscar Niemeyer’s Mid-Twentieth-Century Residential Buildings Styliane Philippou [email protected] +44 20 7619 0045 Keywords: Oscar Niemeyer; architecture; Modernism; Brazilian city; mestiçagem; social, racial and gender city hierarchies Abstract This paper discusses the ways in which Oscar Niemeyer’s mid-twentieth-century residential buildings for the rapidly growing Brazilian cities challenged prevailing assumptions about the hierarchies of the city, and the profoundly patriarchal, white-dominated Brazilian society. The aesthetics of randomness and utilitarian simplicity of Niemeyer’s first house for himself (Rio de Janeiro, 1942) steered clear of any romanticisation of poverty and social marginalisation, but posited the peripheral, urban popular Black architecture of the morros as a legitimate source of inspiration for modern Brazilian residential architecture. At a time of explosive urban growth in Latin American cities, suburban developments allured those who could afford it to flee the city and retreat in suburbia. Niemeyer’s high density residential environment (Copan Apartment Building, 1951, São Paulo), right in the centre Brazil’s industrial metropolis, configured a site of resistance to urban flight and the ‘bourgeois utopia’ of the North American suburban, picturesque enclaves insulated from the workplace. The Copan’s irrational, feminine curves contrasted sharply with the ‘cold, hard, unornamental, technical image’ (Ockman) of the contemporaneous New York City Lever House, typical of the North American corporate capitalist landscape. At a time when Taylorism- influenced zoning was promoted as the solution to all urban problems, the Copan emphatically positioned in the city centre the peripheral realm of domestic, tropical, feminine curves, challenging prevailing images of the virile city of male business and phallic, stifling skyscrapers. -

Selena K. Anders

CURRICULUM VITAE SELENA K. ANDERS Via Ostilia, 15 Rome, Italy 00184 +39 334 582-4183 [email protected] Education “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Ph.D.; Rome, Italy Department of Architecture-Theory and Practice, December 2016 under the supervision of Antonino Saggio and Simona Salvo University of Notre Dame, M.Arch; Notre Dame, Indiana School of Architecture, cum laude May 2009. Archeworks, Postgraduate Certificate; Chicago, Illinois Social and Environmental Urban Design, May 2006. DePaul University, B.A.; Chicago Illinois Art History and Anthropology, Minor in Italian Language and Literature, magna cum laude, June 2005. Academic Positions Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame 2016-Present Co-Director China Summer Study Program, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame 2010-Present Faculty, Office of Pre-College Programs, University of Notre Dame Rome: History, Culture, and Experience, 2015 Co-Director and Co-Founder of HUE/ND (Historic Urban Environments Notre Dame) School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame, 2014-Present Projects: Cities in Text: Rome Associate Director and Co-Founder of DHARMA LAB (Digital Historic Architectural Research and Material Analysis), School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame, 2006-Present India: Documentation of Mughal Tombs in Agra, India Italy: Documentation of the Roman Forum in Rome, Italy Vatican City: Belvedere Court Professor of the Practice, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame, 2012-Present Faculty, Career Discovery for High School -

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017 What did we spot on the Sarawak and regional heritage scene in the last five months? SARAWAK Land clearing observed early March just uphill from the Bongkissam archaeological site, Santubong, raised alarm in the heritage-sensitive community because of the known archaeological potential of the area (for example, uphill from the shrine, partial excavations undertaken in the 1950s-60s at Bukit Maras revealed items related to the Indian Gupta tradition, tentatively dated 6 to 9th century). The land in question is earmarked for an extension of Santubong village. The bulldozing was later halted for a few days for Sarawak Museum archaeologists to undertake a rapid surface assessment, conclusion of which was that “there was no (…) artefact or any archaeological remains found on the SPK site” (Borneo Post). Greenlight was subsequently given by the Sarawak authorities to get on with the works. There were talks of relocating the shrine and, in the process, it appeared that the Bongkissam site had actually never been gazetted as a heritage site. In an e-statement, the Sarawak Heritage Society mentioned that it remained interrogative and called for due diligences rules in preventive archaeology on development sites for which there are presumptions of historical remains. Dr Charles Leh, Deputy Director of the Sarawak Museum Department mentioned an objective to make the Santubong Archaeological Park a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2020. (our Nov.2016-Feb.2017 Newsletter reported on this latter project “Extension project near Santubong shrine raises concerns” – Borneo Post, 22 March 2017 “Bongkissam shrine will be relocated” – Borneo post, 23 March 2017 “Gazette Bongkissam shrine as historical site” - Borneo Post. -

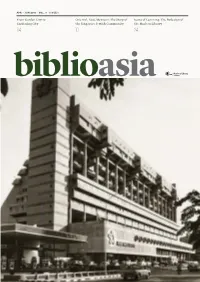

Apr–Jun 2013

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

Hijjas Kasturi and Harry Seidler in Malaysia

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 30, Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, July 2-5, 2013. http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/sahanz-2013/ Amit Srivastava, “Hijjas Kasturi and Harry Seidler in Malaysia: Australian-Asian Exchange and the Genesis of a ‘Canonical Work’” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 30, Open, edited by Alexandra Brown and Andrew Leach (Gold Coast, Qld: SAHANZ, 2013), vol. 1, p 191-205. ISBN-10: 0-9876055-0-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9876055-0-4 Hijjas Kasturi and Harry Seidler in Malaysia Australian-Asian Exchange and the Genesis of a “Canonical Work” Amit Srivastava University of Adelaide In 1980, months after his unsuccessful competition entries for the Australian Parliament House and the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank headquarters, Harry Seidler entered into collaboration with Malaysian architect Hijjas (bin) Kasturi that proved much more fruitful. Their design for an office building for Laylian Realty in Kuala Lumpur was a departure from Seidler’s quadrant geometries of the previous decade, introducing a sinuous “S” profile that would define his subsequent work. Although never realised, Kenneth Frampton has described this project as a “canonical work” that was the “basic prototype for a new generation of medium to high-rise commercial structures.” But Seidler’s felicitous collaboration with Hijjas was evidently more than just circumstantial, arising from a longer term relationship that is part of a larger story of Australian-Asian exchange. -

INTI JOURNAL | Eissn:2600-7320 Vol.2020:062 DESTINATION IMAGE, HYPERREALITY, UNREAL IMAGE THROUGH FILMS

INTI JOURNAL | eISSN:2600-7320 Vol.2020:062 DESTINATION IMAGE, HYPERREALITY, UNREAL IMAGE THROUGH FILMS. A CASE STUDY OF THE FILM CRAZY RICH ASIANS 1 Sriganeshvarun Nagaraj, 2Anil Aaron Selvaram 1,2INTI International University, Malaysia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Crazy Rich Asians was one on the biggest hypes of cinema, from the Asian community and worldwide. It had an even bigger impact for Malaysians as Singapore was a stone throw away from Malaysia. The movie was a huge success within the Asian community, box office forking in international gross of $239 million, from just $30 million production budget. In October 2018, it was crowned the highest-grossing genre of romantic comedy from the last decade. However, the movie portrayal of Singapore was but a mere hyperreality and unreal image. Malaysia was a huge part of the film and was not given the credit it was due. The data was gathered using qualitative research method. In-depth interviews conducted with the sample, which were nine locals and 2 internationals selected based on criterion sampling. The data gathered was analysed based on 5 main themes, Tourism of Malaysia, portrayal of Malaysia, emotions of viewers, misrepresentation, and the awareness of viewers. Based on the data gathered locals and internationals viewers of the film feel negatively towards Crazy Rich Asians because of the potential that it could have on the Tourism of Malaysia. The respondent felt that the director could have given Malaysia its due credit rather than in the end credits. Keywords Film, Unreal Image, Destination Image, Misrepresentation, Hyperreality, Case Study Introduction From the Cinema to the home television, films had always played an impact on the viewers perception of how they see the world. -

THE U.S. STATE, the PRIVATE SECTOR and MODERN ART in SOUTH AMERICA 1940-1943 By

THE U.S. STATE, THE PRIVATE SECTOR AND MODERN ART IN SOUTH AMERICA 1940-1943 by Olga Ulloa-Herrera A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA The U.S. State, the Private Sector and Modern Art in South America 1940-1943 A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Olga Ulloa-Herrera Master of Arts Louisiana State University, 1989 Director: Michele Greet, Associate Professor Cultural Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2014 Olga Ulloa-Herrera All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to Carlos Herrera, Carlos A. Herrera, Roberto J. Herrera, and Max Herrera with love and thanks for making life such an exhilarating adventure; and to María de los Angeles Torres with gratitude and appreciation. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair Dr. Michele Greet and to my committee members Dr. Paul Smith and Dr. Ellen Wiley Todd whose help, support, and encouragement made this project possible. I have greatly benefited from their guidance as a student and as a researcher. I also would like to acknowledge Dr. Roger Lancaster, director of the Cultural Studies Program at George Mason University and Michelle Carr for their assistance throughout the years.