Songs by Hsiao Tyzen: the Interaction Between His Music and Taiwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal XXV I I 1994

JEFFREY HOLLANDER The Artistry of Myra Hess: Recent Reissues Dame Myra Hess-Vol. I Pearl GEMM CD 9462 Jin, Felix Salmond, 'cello), Brahms: Piano [Pearl I] (69'40") Trio in C Major, op. 87 (with Jelly d'Aranyi, Contents: Bach: French Suite no. 5, BWV violin, Gaspar Cassad6, 'cello) 816: Gigue; Schubert: Sonata in A Major, D. 664; Schubert: Rosamunde, 'Ballet Music' Dame Myra Hess (1890-1965) EMI CDH 7 (arr. Ganz); Beethoven: Sonata in A Major, 63787 2 [EM!] (75'57") op. 69 (with Emanuel Feuermann, 'cello); Contents: Beethoven: Piano Sonata in E Chopin: Nocturne in F-sharp Major, op. 15, Major, op. 109; Piano Sonata in A-flat no. 2; Mendelssohn: Song without Words in Major, op. 110; Scarlatti: Sonata in C A-flat Major, op. 38, no. 6; Brahms: Minor, K. 11/L. 352; Sonata in G Major, K. Capriccio in B Minor, op. 76, no. 2; Dvorak: 14/L. 387; Beethoven: Fur Elise; Bagatelle Slavonic Dance in C Major, op. 46, no. 1 in E-flat Major, op. 126, no. 3; (with Hamilton Harty, piano); Debussy: Mendelssohn: Song without Words in A Images, Book II, 'Poissons d'or'; Preludes, Major, op. 102, no. 5; Granados: Goyescas Book I, 'La fille aux cheveux de Jin' and no. 4, 'La maja y el ruiseiior'; Brahms: 'Minstrels'; Bach: Chorale, 'Jesu, Joy of Waltz in A-flat Major, op. 39, no. 15; Man's Desiring' (arr. Hess) Intermezzo in C Major, op. 119, no. 3; J.S. Bach: Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue, BWV Dame Myra Hess-Vol. II Pearl GEMM CD 564: Adagio (arr. -

SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL Uma Análise Comparativa Entre Brasil E Itália UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA

SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA REITOR João Carlos Salles Pires da Silva VICE-REITOR Paulo Cesar Miguez de Oliveira ASSESSOR DO REITOR Paulo Costa Lima EDITORA DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA DIRETORA Flávia Goulart Mota Garcia Rosa CONSELHO EDITORIAL Alberto Brum Novaes Angelo Szaniecki Perret Serpa Caiuby Alves da Costa Charbel Niño El Hani Cleise Furtado Mendes Evelina de Carvalho Sá Hoisel Maria do Carmo Soares de Freitas Maria Vidal de Negreiros Camargo O presente trabalho foi realizado com o apoio da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de pessoal de nível superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Código de financiamento 001 F. Humberto Cunha Filho Tullio Scovazzi organizadores SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália também com textos de Anita Mattes, Benedetta Ubertazzi, Mário Pragmácio, Pier Luigi Petrillo, Rodrigo Vieira Costa Salvador EDUFBA 2020 Autores, 2020. Direitos para esta edição cedidos à Edufba. Feito o Depósito Legal. Grafia atualizada conforme o Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa de 1990, em vigor no Brasil desde 2009. capa e projeto gráfico Igor Almeida revisão Cristovão Mascarenhas normalização Bianca Rodrigues de Oliveira Sistema de Bibliotecas – SIBI/UFBA Salvaguarda do patrimônio cultural imaterial : uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália / F. Humberto Cunha Filho, Tullio Scovazzi (organizadores). – Salvador : EDUFBA, 2020. 335 p. Capítulos em Português, Italiano e Inglês. ISBN: -

Honor Choirs! Pre-Conference [email protected] - Website: Europacantatjunior

INTERNATIONAL CHORAL BULLETIN ISSN - 0896-0968 Volume XXXIX, Number 3 ICB 3rd Quarter, 2020 - English DOSSIER Composer’s Corner: BASIC COGNITIVE PROCESSES Choral Music is an Expression of our IN CONDUCTING Souls and our Social Togetherness Interview with John Rutter INTERNATIONAL CHORAL BULLETIN CONTENTS 3rd Quarter 2020 - Volume XXXIX, Number 3 COVER John Rutter 1 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Emily Kuo Vong DESIGN & CONTENT COPYRIGHT © International Federation DOSSIER for Choral Music 3 BASIC COGNITIVE PROCESSES IN CONDUCTING Theodora Pavlovitch PRINTED BY PixartPrinting.it, Italy IFCM NEWS 13 IFCM AND THE QATAR NATIONAL CHORAL ASSOCIATION WORKING ON SUBMITTING MATERIAL THE WORLD SYMPOSIUM ON CHORAL MUSIC 2023/2024 When submitting documents to be IFCM Press Release considered for publication, please provide articles by Email or through the CHORAL WORLD NEWS ICB Webpage: 15 REMEMBERING COLIN MAWBY http://icb.ifcm.net/en_US/ Aurelio Porfiri proposeanarticle/. The following 18 CHOIRS AND CORONA VIRUS ... THE DAY AFTER electronic file formats are accepted: Aurelio Porfiri Text, RTF or Microsoft Word (version 97 21 CHATTING WITH ANTON ARMSTRONG or higher). Images must be in GIF, EPS, A PROUD MEMBER OF THE INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION FOR CHORAL TIFF or JPEG format and be at least MUSIC FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS 300dpi. Articles may be submitted in one Andrea Angelini or more of these languages: English, French, German, Spanish. IMPOSSIBLE INTERVIEWS 27 THE TRUE HISTORY OF THE VESPERS OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN REPRINTS BY ALESSANDRO GRANDI Articles may be reproduced for non Andrea Angelini commercial purposes once permission has been granted by the managing editor CHORAL TECHNIQUE and the author. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

St. Olaf Choir & St

Founded in 1874 by Norwegian Lutheran immi- grants, St. Olaf is a nationally ranked liberal arts college located in Northfield, Minnesota, approximately 70 km south of the Twin Cities of Minne- apolis and St. Paul, the largest metropolitan area in the upper Midwest. St. Olaf is home to 3,000 students from nearly every state in the country and more than 80 countries and offers 85-majors, concentrations, and academic programs. For more than half a century, St. Olaf students have taken advantage of international and off-campus study programs — including in Norway — that offer profound, life-changing experiences. Living and studying abroad is fundamental to understanding other cultures and perspectives and to becoming an educated citizen in a changing world. go.stolaf.edu I 1874 ble St. Olaf College grunnlagt av norske lutherske immigranter, og er i dag en høyt ansett liberal arts college. Skolen ligger i Northfield, Minnesota, ca 70 kilometer sør for tvillingbyene; Minneapolis og St. Paul, som er den største metropolen i den nordlige delen av midtvesten. St. Olaf huser 3,000 studenter fra nesten samtlige amerikanske stater, mer enn 80 land, og kan tilby over 85 ulike typer bachelorprogrammer og fagkonsentrasjoner. I nesten 50 år har St. Olaf studenter hatt stort utbytte av å ta del i internas- jonale utvekslingsprogrammer — blant annet i Norge — som skaper meningsfulle opplevelser og minner for livet. Verden er i rask endring, derfor er det å bo og studere i utlandet helt fundamentalt for å forstå andre kulturer og perspektiver, og på den måten bli en samfunnsorientert borger. 1 ST. -

Enigma Return to Innocence Mp3, Flac, Wma

Enigma Return To Innocence mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Return To Innocence Country: Europe Released: 1993 Style: Downtempo, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1882 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1644 mb WMA version RAR size: 1411 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 629 Other Formats: WAV AHX AAC MOD DTS MP3 XM Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Return To Innocence (Radio Edit) 4:03 Return To Innocence (Long & Alive Version) 2 7:07 Remix – Curly M.C., Jens Gad Return To Innocence (380 Midnight Mix) 3 5:55 Remix – Jens Gad 4 Return To Innocence (Short Radio Edit) 3:01 Sadeness Part I (Radio Edit) 5 Lyrics By – Curly M.C., David FairsteinMusic By – Curly M.C., F. GregorianProducer – 4:17 Enigma Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Copyright (c) – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Pressed By – EMI Jax Credits Producer, Engineer – "Curly" Michael Cretu* (tracks: 1 to 4) Vocals [Additional] – Angel* (tracks: 1 to 4) Written-By – Curly M.C. (tracks: 1 to 4) Notes Issued in a standard jewel case with front and rear inserts, black disc tray. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (String): 724383842322 Barcode (Text): 7 2438 38423 2 2 Matrix / Runout: 38423-2 MO RE1 S4120F Y 1-1-1 EMI JAX Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 7243 8 92197 2 Virgin, 7243 8 92197 2 Return To Innocence 2, 8 92197 2, Enigma Virgin, 2, 8 92197 2, Europe 1993 (CD, Maxi) DINSD 123 Virgin DINSD 123 Enigma = エニグマ* - VJCP-12015, Enigma Return To Innocence Virgin, VJCP-12015, Japan 1994 DINSD 123 = エニグマ* = リターン・トゥ・イノセンス Virgin DINSD 123 (CD, EP) 7243 8 92197 6 Virgin, 7243 8 92197 6 Return To Innocence UK & 0, DINST 123, 8 Enigma Virgin, 0, DINST 123, 8 1993 (12", Maxi) Europe 92197 6 Virgin 92197 6 7243 8 92197 2 Virgin, 7243 8 92197 2 Return To Innocence 2, 8 92197 2, Enigma Virgin, 2, 8 92197 2, Europe 1993 (CD, Maxi) DINSD 123 Virgin DINSD 123 Return To Innocence 4KM-38423 Enigma Charisma 4KM-38423 US 1993 (Cass, Single) Related Music albums to Return To Innocence by Enigma Enigma - MCMXC a.D. -

The Amis Harvest Festival in Contemporary Taiwan A

?::;'CJ7 I UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY. THE AMIS HARVEST FESTIVAL IN CONTEMPORARY TAIWAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'IIN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC MAY 2003 BY Linda Chiang Ling-chuan Kim Thesis Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Ricardo Trimillos Robert Cheng ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would never have been able to finish this thesis without help from many people and organizations. I would like to first thank my husband Dennis, and my children, Darrell, Lory, Lorinda, Mei-ling, Tzu-yu, and Darren, for their patience, understanding, and encouragement which allowed me to spend two entire summers away from home studying the culture and music of the Amis people of Taiwan. I especially want to thank Dennis, for his full support of my project. He was my driver and technical assistant during the summer of 1996 as I visited many Amis villages. He helped me tape and record interviews, songs, and dances, and he spent many hours at the computer, typing my thesis, transcribing my notes, and editing for me. I had help from friends, teachers, classmates, village chiefs and village elders, and relatives in my endeavors. In Taiwan, my uncles and aunts, T'ong T'ien Kui, Pan Shou Feng, Chung Fan Ling, Hsu Sheng Ming, Chien Su Hsiang, Lo Ch'iu Ling, Li Chung Nan, and Huang Mei Hsia, all helped with their encouragement and advice. They also provided me with rides, contacts, and information. Special thanks goes to T'ong T'ien Kui and Chung Fan Ling who drove me up and down mountains, across rivers and streams, and accompanied me to many of the villages I wanted to visit. -

Division, Records of the Cultural Affairs Branch, 1946–1949 108 10.1.5.7

RECONSTRUCTING THE RECORD OF NAZI CULTURAL PLUNDER A GUIDE TO THE DISPERSED ARCHIVES OF THE EINSATZSTAB REICHSLEITER ROSENBERG (ERR) AND THE POSTWARD RETRIEVAL OF ERR LOOT Patricia Kennedy Grimsted Revised and Updated Edition Chapter 10: United States of America (March 2015) Published on-line with generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), in association with the International Institute of Social History (IISH/IISG), Amsterdam, and the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, at http://www.errproject.org © Copyright 2015, Patricia Kennedy Grimsted The original volume was initially published as: Reconstructing the Record of Nazi Cultural Plunder: A Survey of the Dispersed Archives of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), IISH Research Paper 47, by the International Institute of Social History (IISH), in association with the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, and with generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), Amsterdam, March 2011 © Patricia Kennedy Grimsted The entire original volume and individual sections are available in a PDF file for free download at: http://socialhistory.org/en/publications/reconstructing-record-nazi-cultural- plunder. Also now available is the updated Introduction: “Alfred Rosenberg and the ERR: The Records of Plunder and the Fate of Its Loot” (last revsied May 2015). Other updated country chapters and a new Israeli chapter will be posted as completed at: http://www.errproject.org. The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the special operational task force headed by Adolf Hitler’s leading ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, was the major NSDAP agency engaged in looting cultural valuables in Nazi-occupied countries during the Second World War. -

Selected Taiwanese Art Songs of Hsiao Tyzen

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Selected Taiwanses Art Songs of Hsiao Tyzen Hui-Ting Yang Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC SELECTED TAIWANESE ART SONGS OF HSIAO TYZEN By HUI-TING YANG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Hui-Ting Yang All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Hui-Ting Yang defended on April 28, 2006. __________________________ Timothy Hoekman Professor Directing Treatise __________________________ Ladislav Kubik Outside Committee Member __________________________ Carolyn Bridger Committee Member __________________________ Valerie Trujillo Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to my parents, Mr. Yang Fu-Hsiang (GJI) and Mrs. Hsieh Chu-Leng (HF!), and my uncle, Mr. Yang Fu-Chih (GJE) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks go to my treatise committee members, not only for their suggestions and interest in this treatise but also for their support and encouragement during all the working process. My great admiration goes to my treatise director, Dr. Timothy Hoekman, who spent endless hours reading my paper and making corrections for me, giving me inspiring ideas during each discussion. My special thanks go to my major professor, Dr. Carolyn Bridger, who offered me guidance, advice, and continuous warm support throughout my entire doctoral studies. I am thankful for her understanding and listening to my heart. -

3. Study Chinese in Beautiful Taiwan

TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 10 Reasons for Learning Chinese in Taiwan 04 Getting to Know Taiwan 06 More about Taiwan History Climate Geography Culture Ni Hao Cuisine 08 Applying to Learn Chinese in Taiwan Step-by-Step Procedures 09 Scholarships 10 Living in Taiwan Accommodations Services Work Transportation 12 Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language (TOCFL) Organisation Introduction Test Introduction Target Test Taker Test Content Test Format Purpose of the TOCFL TOCFL Test Overseas Contact SC-TOP 14 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - North 34 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - Central 41 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - South 53 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - East 54 International Students in Taiwan 56 Courses at Chinese Learning Centers 60 Useful Links 學 8. High Standard of Living 華 10 REASONS FOR Taiwan’s infrastructure is advanced, and its law-enforcement and transportation, communication, medical and public health systems are 語 LEARNING CHINESE excellent. In Taiwan, foreign students live and study in safety and comfort. 9. Test of Chinese as Foreign IN TAIWAN Language (TOCFL) The Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language (TOCFL), is given to international students to assess their Mandarin Chinese listening 1. A Perfect Place to Learn Chinese and reading comprehension. See p.12-13 for more information) Mandarin Chinese is the official language of Taiwan. The most effective way to learn Mandarin is to study traditional Chinese characters in the modern, Mandarin speaking society of Taiwan. 10. Work While You Study While learning Chinese in Taiwan, students may be able to work part-time. Students will gain experience and a sense of accomplishment LEARNING CHINESE IN TAIWAN 2. -

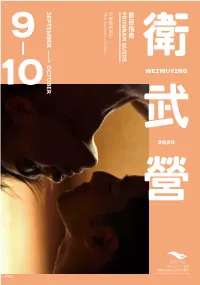

Sep Tember Oc Tober

SEPTEMBER PROGRAM GUIDE The Journey of love of Journey The 9 OCTOBER 10 WEIWUYING 2020 © 1 Contents 004 9 September Program Calender 006 10 October Program Calender 010 Feature 014 9 September Programs 036 10 October Programs 079 Exhibition 080 Activity Opening Hours 104 Tour Service 11:00-21:00 105 Become Our Valued Friend Service Center (Box Office) 106 Visit Us 11:00-21:00 For more information weiwuying_centerforthearts @weiwuying @weiwuying_tw COVID-19 National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts (Weiwuying) Preventive Measures against the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Epidemic Please follow the policies below before entering the venue A Special Plan for Performers 60 Performers can get a full refund for the rent if cancel the show 60 days before the scheduled date. Technical tests and rehearsals require no fee. 50% Rents are 50% off in the following situations: Audience are required to sit at intervals. / Live shows are changed into online streaming or recorded videos. / First-time auditorium rental for online streaming or video recording First-time auditorium rental for technical tests and rehearsals If you change the auditorium reservation from the original one into a larger one, the prices remain unchanged. Please contact us for the following ticketing matters. For the shows cancelled with a purpose of pandemic prevention, domestic performance teams have the priority to schedule the time in the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2021. Weiwuying will keep updating this special plan according to National Health Command Center policies. Weiwuying will work together with the public in preventing the spread of the epidemic and building a comfortable and safe venue. -

The Revitalization of Love River Kaohsiung, Taiwan

台灣,高雄市愛河生命活化的沿革 The Revitalization of Love River Kaohsiung ,Taiwan 陳繼志 Chi-tze Chen Former Director General of Public Works Bureau, Kaohsiung City Government TAIWAN 2007.10.11 Data of Kaohsiung City • Population : 1.52 million • Area : 178k ㎡ • Annual rainfall volume : 1,780mm( Jun the highest rainfall of 398mm) I. Origin of Love River Before 1895 Love River was transformed from shallow sea, low-lying land, swamp, and then the tangled waterway of the river showed up.The map drawn by the Dutchmen in 17 century had illustrated Love River, but the river had not been named yet. The Chinese called a section of a river “Gang,” which means a port, in Ching Dynasty. The Gang from upstream the downstream were Chuan-zi-tou Gang, Tien-wei Gang, Long-shuei Gang, and Yen-cheng Gang. 1895-1947 The former name of Kaohsiung is Takau. Since Love River had not had a formal name then, it was named Takau River.In 1920, “Takau” was renamed as “Takao(高雄)”. In 1935, the Port of Kaohsiung was built. In order to ship the 1 logs to the downstream and to cooperate with the reclamation plan of Yen-cheng District, the river was dredged and expanded 73~128 meter in width and 3.6 meter in depth. The river became “Kaohsiung Canal”, the ship canal for industrial use, and was thus formally named Kaohsiung River. This was the first time that the river had a formal name. 1948-1952 In 1948, there was a “Lover River Cruise Company” opened near Jhong-Jheng Bridge. The shop sign was destroyed by a Typhoon and only “Love River” of the sign was left.Later on a reporter who accounted the event of a couple committing suicide by jumping into the river mistook “Lover River” as the name of the river.