Synthesis Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum vitae Martijn van Welie Design Director Personal data Name Martijn van Welie Degree Ph.D. in Human Computer Interaction Date of birth 09-09-1973 Gender Male Nationality Dutch Address Amsteldijk 50-III Zip code 1074HW Amsterdam Key Competence areas Design I am specialized in Interaction Design for web and mobile applications. My main skills include developing interactive concepts, developing persona's, conducting task analysis, wireframing, planning and execution of usability tests. In my work I have intensive contact with both the client and the design team in order to work on the client's wishes while balancing budget and technical constraints. In my research time I work on future technologies in our field as well as the development of a body of knowledge on interaction design by developing a Pattern Language for Interaction Design. See www.welie.com/patterns for more information on my work on patterns Project Management I have some basic project management skills and do most of the design- related management activities in regular projects. This include working with clients on outlining to project, making sure regular progress is being made and working with the design team to align the design, technical and business requirements. Recently I have worked 9 months as a contractor for Vodafone Netherlands where I held the position of ad interim Studio manager for Vodafone live! page 1 of 5 Selected Projects TMF (2004) In the fall of 2004 I was the concept designer for the new TMF site, owned by MTV Networks. The site is a real broadband site where audio and video content was used to enhance the user experience. -

Annex 4: Report from the States of the European Free Trade Association Participating in the European Economic Area

ANNEX 4: REPORT FROM THE STATES OF THE EUROPEAN FREE TRADE ASSOCIATION PARTICIPATING IN THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AREA 1. Application by the EFTA States participating in the EEA 1.1 Iceland European works The seven covered channels broadcast an average of 39.6% European works in 2007 and 42.2% in 2008. This represents a 2.6 percentage point increase over the reference period. For 2007 and 2008, of the total of seven covered channels, three channels achieved the majority proportion specified in Article 4 of the Directive (Omega Television, RUV and Syn - Vision TV), while four channels didn't meet this target (Sirkus, Skjár 1, Stöð 2 and Stöð 2 Bio). The compliance rate, in terms of numbers of channels, was 42.9%. European works made by independent producers The average proportion of European works by independent producers on all reported channels was 10.7% in 2007 and 12.6% in 2008, representing a 1.9 percentage points increase over the reference period. In 2007, of the total of seven identified channels, two channels exceeded the minimum proportion under Article 5 of the Directive, while three channels remained below the target. One channel was exempted (Syn - Vision TV) and no data was communicated for another one (Omega Television). The compliance rate, in terms of number of channels, was 33.3%. For 2008, of the total of seven covered channels, three exceeded the minimum proportion specified in Article 5 of the Directive, while two channels were below the target (Skjár 1 and Stöð 2 Bio). No data were communicated for two channels. -

Drinks Industry Initiatives 2008

Drinks Industry Initiatives 2008 Voluntary initiatives by the EU spirits industry to help reduce alcohol-related harm IndexPREFACE p. 04 Hungary p. 28 INTRODUCTION p. 04 Ireland p. 30 PRACTICAL INFORMATION p. 05 Italy p. 34 Austria p. 06 The Netherlands p. 36 Belgium p. 06 Poland p. 40 Bulgaria p. 08 Portugal p. 45 Czech Republic p. 09 Slovakia p. 45 Denmark p. 11 Slovenia p. 46 European Union p. 13 Spain p. 46 Finland p. 18 Sweden p. 53 France p. 18 United Kingdom p. 54 Germany p. 23 Greece p. 27 LIST OF ORGANISATIONS AND MEMBERS p. 66 Drinks Industry Initiatives 03 2008 Preface This brochure, produced annually since 2005, is the result of the combined work of the European Forum for Responsible Drinking (EFRD) and the European Spirits Organisation – CEPS. ✚ EFRD is an alliance of leading European alcoholic beverages producers supporting targeted initiatives to promote responsible drinking. These initiatives focus on attitudinal and awareness programme responsible marketing and self-regulation, and the promotion of a better understanding of the evidence base. EFRD promotes the partnership approach with interested stakeholders to tackle alcohol-related harm. EFRD members include: Bacardi-Martini, Brown-Forman, Diageo, Moët-Hennessy, Pernod-Ricard, Rémy Cointreau and Beam Global Spirits & Wine. ✚ The European Spirits Organisation – CEPS acts as the European representative body for producers of spirit drinks. Its membership comprises 35 national associations representing the industry in 29 European countries, as well as a group of leading spirits producing companies including the members of EFRD. The European Spirits Organisation – CEPS aims to raise and promote the understanding of the EU spirits industry to decision makers in the EU institutions, international organisations and other key stakeholders. -

Inhoud Pagina 1. Inleiding 1 2. Scenarioplanning En De Scenario's

Inhoud pagina 1. Inleiding 1 2. Scenarioplanning en de scenario’s 4 3. Televisie: een medium in beweging 8 Televisual revolution 8 Push, pull en flow 9 Liveness 10 4. MTV Networks in het nieuwe medialandschap 13 De organisatie MTV Networks 13 MTV: oorsprong in muziek, toekomst in…? 14 5. De scenario’s 16 5.1 Snack 16 MTV Networks in het Snackscenario 19 5.2 Picknick 23 MTV Networks in het Picknickscenario 27 5.3 Lopend buffet 29 MTV Networks in het Lopend buffetscenario 31 5.4 Hollandse pot 35 MTV Networks in het Hollandse potscenario 38 6. Conclusie 41 7. Bronnen 43 Bijlage Aristoteles Voorbij, Het medialandschap in 2015 1. Inleiding Commerciële televisie is voor het grootste gedeelte van haar inkomsten afhankelijk van reclamebestedingen. De kijkers worden als het ware verkocht door de televisiezenders aan de adverteerders. Verschillende technologische ontwikkelingen zorgen er echter voor dat deze kijkers steeds minder reclameblokken zien. Sinds de komst van de videocassetterecorder in de jaren zeventig werd het voor de kijker namelijk mogelijk om programma’s op te nemen en de reclames door te spoelen. Voor de kijker is het sindsdien steeds makkelijker geworden om reclameblokken te ontwijken, want tegenwoordig is het door de komst van de harddiskrecorder zelfs niet meer nodig om te wachten tot de opname afgelopen is om de uitzending te bekijken. Daarnaast verplaatsen steeds meer kijkers zich naar het internet, 1 waar de kijker helemaal geen reclames hoeft te zien of waarbij de reclames beperkt worden tot een enkele advertentie voorafgaande aan de uitzending. Naast de mogelijkheden die nieuwe technologieën de televisiegebruiker bieden, zijn er ook andere redenen waarom televisiekijkers minder reclame zien: ze ontwijken de reclames door naar andere zenders te zappen tijdens reclameblokken en gaan andere dingen doen zoals koffie zetten. -

De Dj Als Superster Universiteit Universiteit Van Utrecht Auteur J.H

Titel doctoraalscriptie De dj als superster Universiteit Universiteit van Utrecht Auteur J.H. Meeuwissen Studierichting Taal en Cultuurstudies Adres Waalstraat 93hs Specialisatie Kunstbeleid en Management Woonplaats Amsterdam Eerste lezer drs. Ingmar Leijen Telefoon 06-51819744 Tweede lezer dr. Kees Vuyk Studentnummer 0067016 Datum mei 2007 - de dj als superster - 2 Samenvatting In De dj als superster wordt een vergelijking getrokken tussen de superster uit de popmuziek en de dj uit de dancewereld. De thesis legt overeenkomsten en verschillen in marketingtechnieken tussen de popmuziekwereld en de dancemuziekwereld bloot. De opkomst en creatie van de superster in de jaren tachtig worden bestudeerd, alsmede de geschiedenis van dancemuziek en marketingtechnieken in de dancescene. Hierdoor komen ook enkele fundamentele verschillen tussen deze twee muziekwerelden aan het licht. De dj is aan het einde van de 20 e eeuw het middelpunt geworden van de dancescene. Het uitgebreide takenpakket van een dj vertoont overeenkomsten met het takenpakket van een superster in de popmuziek. Ook op het gebied van de marketing zijn er diverse overeenkomsten gevonden in dit onderzoek. Hier zijn echter ook belangrijke verschillen aan het licht gekomen. Uit de interviews met specialisten uit de dancewereld blijkt dat de marketingmethodes die zij gebruiken, voor een groot deel overeenkomen met de benodigdheden die gevonden werden voor het bereiken van de supersterstatus in de popmuziek in de jaren tachtig. Vier van die zeven benodigdheden, te weten het verzorgen van optredens, wereldwijde distributie, cross-overs en weinig aanbod op het gebied van optredens, worden volledig identiek ook toegepast in de marketing van dj’s. Slechts met één punt, het bezitten van sex appeal, wordt op dit moment niets gedaan door de specialisten uit de dance-industrie. -

Intercontinental Exchange

Intercontinental Exchange Date Symbol Short Exempt Short Volume Total Volume Market Volume 20201029 AA 2232 381448 2243526 N 20201029 AAAU 0 26400 29257 N 20201029 AACQ 0 53547 65100 N 20201029 AACQW 0 400 400 N 20201029 AAIC 64 9531 20538 N 20201029 AAIC PRB 0 1 2001 N 20201029 AAIC PRC 0 330 1030 N 20201029 AAL 410 1585694 2347234 N 20201029 AAN 2389 114269 307150 N 20201029 AAOI 0 756 2779 N 20201029 AAON 0 822 1308 N 20201029 AAP 350 94314 153331 N 20201029 AAPL 13374 1488668 2795715 N 20201029 AAT 3429 48478 112783 N 20201029 AAU 600 3039 6136 N 20201029 AAWW 0 2702 6094 N 20201029 AAXJ 0 46391 60802 N 20201029 AAXN 0 2756 4751 N 20201029 AB 597 48505 87287 N 20201029 ABB 2637 317330 406641 N 20201029 ABBV 21051 864518 1705722 N 20201029 ABC 650 243426 392362 N 20201029 ABCB 10 1964 3118 N 20201029 ABCM 0 200 336 N 20201029 ABEO 0 35637 50358 N 20201029 ABEV 11199 9331825 10719861 N 20201029 ABG 2669 39740 66383 N 20201029 ABIO 0 525 825 N 20201029 ABM 5492 50543 112061 N 20201029 ABMD 12 4653 6918 N 20201029 ABR 1537 284865 358680 N 20201029 ABR PRA 0 204 204 N 20201029 ABR PRB 0 300 300 N 20201029 ABST 0 1200 1800 N 20201029 ABT 34471 625871 1061463 N 20201029 ABTX 0 307 329 N 20201029 ABUS 0 3300 6020 N 20201029 AC 0 7104 9551 N 20201029 ACA 409 43232 78466 N 20201029 ACACU 0 600 800 N 20201029 ACAD 0 7233 11397 N 20201029 ACAM 0 100 8352 N 20201029 ACB 93171 1194116 1476777 N 1 of 153 Intercontinental Exchange Date Symbol Short Exempt Short Volume Total Volume Market Volume 20201029 ACBI 0 1963 3161 N 20201029 ACC 1564 160105 -

995 Final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels,23.9.2010 SEC(2010)995final COMMISSIONSTAFFWORKINGDOCUMENT Accompanyingdocumenttothe COMMUNICATIONFROMTHECOMMISSIONTOTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT,THECOUNCIL,THEEUROPEANECONOMIC ANDSOCIAL COMMITTEEANDTHECOMMITTEEOFTHEREGIONS NinthCommunication ontheapplicationofArticles4and5ofDirective89/552/EECas amendedbyDirective97/36/ECandDirective2007/65/EC,fortheperiod2007-2008 (PromotionofEuropeanandindependentaudiovisual works) COM(2010)450final EN EN COMMISSIONSTAFFWORKINGDOCUMENT Accompanyingdocumenttothe COMMUNICATIONFROMTHECOMMISSIONTOTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT,THECOUNCIL,THEEUROPEANECONOMIC ANDSOCIAL COMMITTEEANDTHECOMMITTEEOFTHEREGIONS NinthCommunication ontheapplicationofArticles4and5ofDirective89/552/EECas amendedbyDirective97/36/ECandDirective2007/65/EC,fortheperiod20072008 (PromotionofEuropeanandindependentaudiovisual works) EN 2 EN TABLE OF CONTENTS ApplicationofArticles 4and5ineachMemberState ..........................................................5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................5 1. ApplicationofArticles 4and5:generalremarks ...................................................5 1.1. MonitoringmethodsintheMemberStates ..................................................................6 1.2. Reasonsfornon-compliance ........................................................................................7 1.3. Measures plannedor adoptedtoremedycasesofnoncompliance .............................8 1.4. Conclusions -

Download (1049Kb)

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 22.7.2008 SEC(2008) 2310 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Accompanying document to the COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Eighth Communication on the application of Articles 4 and 5 of Directive 89/552/EEC ‘Television without Frontiers’, as amended by Directive 97/36/EC, for the period 2005- 2006 [COM(2008) 481 final] EN EN TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 1: Performance indicators...................................................... 3 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 2: Charts and tables on the application of Articles 4 and 5... 6 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 3: Application of Articles 4 and 5 in each Member State ... 12 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 4: Summary of the reports from the Member States ........... 44 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 5: Voluntary reports by Bulgaria and Romania................. 177 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 6: Reports from the Member States of the European Free Trade Association participating in the European Economic Area ......................................... 182 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 7: Average transmission time of European works by channels with an audience share above 3% .. ........................................................................ 187 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 8: List of television channels in the Member States which failed to achieve the majority proportion required by Article 4............................................. 195 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 9: List of television channels in the Member States which failed to achieve the minimum proportion required by Article 5........................................... 213 EN 2 EN BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 1: Performance indicators The following indicators facilitate the evaluation of compliance with the proportions referred to in Article 4 and 5 of the Directive. Indicators 2 – 5 are based on criteria set out in Articles 4 and 5. -

SKO Jaarrapport 2011

SKO Jaarrapportage 2011 Jaarrapport 2011 SKO Jaarrapportage 2011 Jaarrapport 2011 18-01-2012 Pagina 2/78 SKO Jaarrapportage 2011 Noot Dit rapport heeft betrekking op het jaar 2011. Regelmatig wordt in dit jaarrapport een vergelijking gemaakt met 2010. Vanaf maandag week 1 2008 is het uitgesteld kijken (via bijvoorbeeld video, dvd- en harddisk recorder) geïntegreerd in de kijkcijfers. In de resultaten die in dit rapport worden gepresenteerd, is uitgesteld kijken binnen zes dagen na de dag van uitzending meegenomen. Een aantal zenders heeft niet heel 2011 uitgezonden. TMF is per 4 april 2011 gestopt met uitzenden. De zenders TeenNick, Kindernet en TLC zijn respectievelijk per 14 febuari, 4 april en 4 juli gestart. Voor deze zenders is de periode waarin zij niet hebben uitgezonden, voor resultaattypen zoals kijkdichtheid, marktaandeel en absolute aantallen, gelijkgesteld met 0. De zender Animal Planet is per 1 maart 2010 opgenomen in de Full Audit. Een aantal digitale zenders heeft niet heel 2010 of 2011 in de rapportering gezeten, hieronder volgt een overzicht van deze zenders. • De zender Eredivisie 3 zit in de rapportering sinds februari 2010. • De zender Hallmark zit in de rapportering sinds maart 2010. • De zender Misdaadnet zit in de rapportering sinds juni 2010. • De zender Het Gesprek heeft in de rapportering gezeten van maart tot en met juli 2010. • De zender Fan TV is per juni 2010 uit de rapportering. • De zender Car Channel is per 13 december 2010 uit de rapportering • De zender Out TV zit in de rapportering sinds 1 september -

Zenderoverzicht Televisie

zenderoverzicht televisie Nederlandse zenders 57 Sat 1 • • Sport 1 Nederland 1 58 Pro Sieben 131 Eurosport • • • • • • • • 2 59 132 aanvullend abonnement TV Digitaal Extra TV Digitaal Nederland 2 • • Kabel 1 • Eurosport 2 • 3 Nederland 3 • • 133 Extreme Sports • 4 RTL 4 • • Britse tv 134 Motors TV • 5 RTL 5 • • 71 BBC 1 • • 135 Sailing Channel • 6 SBS 6 • • 72 BBC 2 • • 136 ESPN Classic Sports • 7 RTL 7 • • 73 BBC 3 / CBBC • 137 NASN (North American Sports Network) • 8 Veronica / Jetix • • 74 BBC 4 / CBeebies • 140 Sport1 Mozaiek • 9 Net 5 • • 75 BBC Prime • 141 Sport1.1 24/7 • 10 Talpa / Nickleodeon • • 142 Sport1.2 • 11 TV Digitaal kanaal • • Overig europees 143 Sport1.3 • 20 ZiZone (v.a. oktober 2006) • • 81 TV5 • • 144 Sport1.4 • 82 RTBF Sat • • 145 Sport1.5 • Regionale omroepen 83 Rai Uno • • 146 Sport1.6 • 21 TV Noord • • 84 TRT Int. • • 147 Sport1.7 • 22 Omrop Fryslân • • 85 TVE Internaçional • 148 Sport1.8 • 23 TV Drenthe • • 149 Sport1 HD ** • 24 TV Oost • • Nieuws & actueel 25 TV Flevoland • • 101 CNN International • • Kennis 26 TV Gelderland • • 102 BBC World • • 151 Discovery Channel • • 27 Omroep Brabant TV • • 103 Euronews • • 152 Animal Planet • • 28 L1 Limburg • • 104 Sky News • 153 National Geographic Channel • • 29 TV Noord-Holland • • 105 Bloomberg • 154 Discovery Travel & Living • 30 AT5 • • 106 CNBC Europe • 155 Discovery Science • 31 TV Utrecht • • 107 Aljazeera International • 156 Discovery Civilisation • 32 TV West • • 157 Travel Channel • 33 TV Rijnmond • • Film 158 Adventure 1 • 34 Omroep Zeeland * • • 111 Film1.1 • 112 Film1.2 • Muziek Vlaamse tv 113 Film1.3 • 171 MTV • • 41 VRT / één • • 114 Film1+1 • 172 The Box • • 42 Ketnet / Canvas • • 115 Film1 HD ** • 173 TMF • • 116 MGM Movie Channel • 174 MTV Brand New • Duitse tv 117 TCM (Turner Classic Movies) • 175 TMF NL • 51 ARD • • 118 Hallmark • 176 TMF Party • 52 ZDF • • 177 MTV 2 • 53 NDR • • Kids 178 MTV Hits • 54 WDR • • 121 Cartoon Network • 179 MTV Base • 55 SWF • • 122 Boomerang • 180 VH-1 • 56 RTL Television • • 123 Nick Jr. -

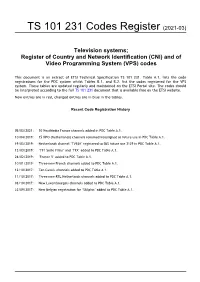

TS 101 231 Codes Register (2021-03)

TS 101 231 Codes Register (2021-03) Television systems; Register of Country and Network Identification (CNI) and of Video Programming System (VPS) codes This document is an extract of ETSI Technical Specification TS 101 231. Table A.1. lists the code registrations for the PDC system whilst Tables B.1. and B.2. list the codes registered for the VPS system. These tables are updated regularly and maintained on the ETSI Portal site. The codes should be interpreted according to the full TS 101 231 document that is available free on the ETSI website. New entries are in red, changed entries are in blue in the tables. Recent Code Registration History 05/03/2021: 10 NextMedia France channels added in PDC Table A.1. 10/04/2019: 15 NPO (Netherlands) channels renamed/reassigned as future use in PDC Table A.1. 19/03/2019: Netherlands channel ’TV538’ registered to SBS future use 3129 in PDC Table A.1. 13/03/2019: ‘TF1 Serie Films’ and ‘TFX’ added to PDC Table A.1. 26/02/2019: ‘France 5’ added to PDC Table A.1. 10/01/2019: Three new French channels added to PDC Table A.1. 12/10/2017: Ten Canal+ channels added to PDC Table A.1. 11/10/2017: Three new RTL Netherlands channels added to PDC Table A.1. 03/10/2017: New Luxembourgois channels added to PDC Table A.1. 22/09/2017: New Belgian registration for ‘SBSplus’ added to PDC Table A.1. 2 TS 101 231 Codes Register (2021-03) Annex A (informative): Register of CNI codes for Teletext based systems Table A.1: Register of Country and Network Identification (CNI) codes for Teletext based systems 8/30 8/ 30 X/ -

I Want My MTV, We Want Our TMF the Music Factory, MTV Europe, and Music Television in the Netherlands, 1995-2011 Kooijman, J

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) I Want My MTV, We Want Our TMF The Music Factory, MTV Europe, and Music Television in the Netherlands, 1995-2011 Kooijman, J. DOI 10.18146/2213-0969.2017.JETHC126 Publication date 2017 Document Version Final published version Published in VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kooijman, J. (2017). I Want My MTV, We Want Our TMF: The Music Factory, MTV Europe, and Music Television in the Netherlands, 1995-2011. VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, 6(11), 93-101. https://doi.org/10.18146/2213-0969.2017.JETHC126 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 volume 6 issue 11/2017 I WANT MY MTV, WE WANT OUR TMF THE MUSIC FACTORY, MTV EUROPE, AND MUSIC TELEVISION IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1995-2011 Jaap Kooijman Media Studies University of Amsterdam Turfdraagsterpad 9 1012 XT Amsterdam The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract: The Dutch music television channel, The Music Factory (TMF), launched in 1995, presented a local alternative to MTV Europe, owned by the US-based conglomerate, Viacom.