File21.Branscum.Qxp Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen. -

Grey Morality of the Colonized Subject in Postwar Japanese Cinema and Contemporary Manga

EITHER 'SHINING WHITE OR BLACKEST BLACK': GREY MORALITY OF THE COLONIZED SUBJECT IN POSTWAR JAPANESE CINEMA AND CONTEMPORARY MANGA Elena M. Aponte A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2017 Committee: Khani Begum, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2017 Elena M. Aponte All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Khani Begum, Advisor The cultural and political relationship between Japan and the United States is often praised for its equity, collaboration, and mutual respect. To many, the alliance between Japan and the United States serves as a testament for overcoming a violent and antagonistic past. However, the impact of the United States occupation and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is rarely discussed in light of this alliance. The economic revival, while important to Japan’s reentry into the global market, inevitably obscured continuing paternalistic interactions between Japan and the United States. Using postcolonial theory from Homi K. Bhahba, Frantz Fanon, and Hiroshi Yoshioka as a foundation, this study examines the ways Japan was colonized during and after the seven-year occupation by the United States. The following is a close assessment of two texts and their political significance at two specific points in history. Akira Kurosawa's1948 noir film Drunken Angel (Yoidore Tenshi) shaped the identity of postwar Japan; Yasuhiro Nightow’s Trigun manga series navigates cultural amnesia and American exceptionalism during the 1990s after the Bubble Economy fell into recession in 1995. These texts are worthy of simultaneous assessment because of the ways they incorporate American archetypes, iconography, and themes into their work while still adhering to Japanese cultural concerns. -

Contents General Information

Contents General Information ............. 2 Costume Contest ...................... 7 Room Parties ................................ 8 Guests of Honor ..................... 10 Tabletop Gaming ...................... 12 Video Gaming ............................ 13 Full Schedule ............................ 14 Panels & Events ......................... 20 Video Rooms .............................. 27 A Note from the Chair Another year has transpired and the staff have been hard at work assembling the following convention. Why haven’t you joined staff yet? It’s awesome. We only do this because of you, the Fanatics and Otaku. Without you, we have no reason to put together the most audacious, expensive thing in our year. It’s be- cause of the dedication and desire to share that the staff, dealers, artists, talent, panelists and guests of honor coalesce to present such an amazing event. I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone, including those who don’t read this, for attending and making this possible. Thank you, Otaku. Thank you, Fanatics. Thank you, Guests of Honor. Thank you, Dealers. Thank you, Artists of the Alley. Thank you, Disk Jockeys (talent). Thank you, Hotel Ramada personnel. Thank you, Panelists. Thank you, Members (guests/attendees). Thank you, Staff of Anime Fusion. Thank you. Did I say, thank you? Let’s all make this the best, yet, Anime Fusion experience for all! This is, Anime Fusion 2015: The Future was Then. Where we explore the vision of our present from the past’s vision of the future. Space operas and spaghetti odysseys, to name a few, as well as westerns and historically based fictions. The Future was Then, as it is now. Share with your friends the wonder that is Anime. -

Bandes Dessinées 47

006_091_Critiques272_Mise en page 1 26/07/13 17:21 Page47 NOUVEAUTÉS BANDES DESSINÉES 47 Ankama Bayard Jeunesse Delcourt Étincelle Mes grandes histoires À partir de 13 ans À partir de 11 ans À partir de 6 ans Scén. Frank Giroud, Ulysse Malassagne a dess. Paolo Grella Kairos, t.1 Galkiddek, t.1 : La Prisonnière Emmanuel Guibert, En suivant Anaëlle à la campagne, dess. Marc Boutavant Voici une nouvelle trilogie signée Frank Nills, amoureux gauche de cette Ariol : Où est Pétula ? (a) Giroud, qui bénéficie pour son jeune femme au caractère lancement d’un blog Ariol, l’ânon bleu à lunettes, est raide indépendant, ne se doute pas que son (http://frankgiroud-galkiddek.blogspot.fr) dingue de Pétula, l’adorable vachette. séjour paisible dans une vieille maison sur la genèse de l’album. Cela Lui déclarer sa flamme malgré sa de famille va le projeter dans un commence un peu doucement dans timidité est son rêve le plus cher, monde parallèle... Car, dès la première ce tome 1, qui n’est qu’une longue bientôt exaucé grâce à une invitation nuit, d’étranges créatures viennent scène d’exposition. Il faut à cet égard à déjeuner et à passer l’après-midi enlever leur «princesse » en fuite. Le surtout ne pas lire la quatrième de chez les Mâchicoulis. Ah, quelle lecteur en apprend alors un peu plus couverture qui en dévoile trop ! Dans délicieuse perspective ! Sauf que le sur le passé de la jeune fille. Et Nills se un beau décor médiéval, il s’agit de tête-à-tête tant attendu ne se retrouve lancé dans des aventures qui suivre la quête du comte de Galkiddek déroulera pas comme prévu ! le dépassent. -

Protoculture Addicts #97 Contents

PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS #97 CONTENTS 47 14 Issue #97 ( July / August 2008 ) SPOTLIGHT 14 GURREN LAGANN The Nuts and Bolts of Gurren Lagann ❙ by Paul Hervanack 18 MARIA-SAMA GA MITERU PREVIEW ANIME WORLD Ave Maria 43 Ghost Talker’s Daydream 66 A Production Nightmare: ❙ by Jason Green Little Nemo’s Misadven- 21 KUJIBIKI UNBALANCE tures in Slumberland ❙ ANIMESample STORIES file by Bamboo Dong ❙ by Brian Hanson 24 ARIA: THE ANIMATION 44 BLACK CAT ❙ by Miyako Matsuda 69 Anime Beat & J-Pop Treat ❙ by Jason Green • The Underneath: Moon Flower 47 CLAYMORE ❙ by Rachael Carothers ❙ by Miyako Matsuda ANIME VOICES 50 DOUJIN WORK 70 Montreal World Film Festival • Oh-Oku: The Women of 4 Letter From The Editor ❙ by Miyako Matsuda the Inner Palace 5 Page 5 Editorial 53 KASHIMASHI: • The Mamiya Brothers 6 Contributors’ Spotlight GIRL MEETS GIRL ❙ by M Matsuda & CJ Pelletier 98 Letters ❙ by Miyako Matsuda 56 MOKKE REVIEWS NEWS ❙ by Miyako Matsuda 73 Live-Action Movies 7 Anime & Manga News 58 MONONOKE 76 Books ❙ by Miyako Matsuda 92 Anime Releases 77 Novels 60 SHIGURUI: 78 Manga 94 Related Products Releases DEATH FRENZY 82 Anime 95 Manga Releases ❙ by Miyako Matsuda Gurren Lagann © GAINAX • KAZUKI NAKASHIMA / Aniplex • KDE-J • TV TOKYO • DENTSU. Claymore © Norihiro Yago / Shueisha • “Claymore” Production Committee. 3 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR ANIME NEWS NETWORK’S Twenty years ago, Claude J. Pelletier and a few of his friends decided to start a Robotech プPROTOCULTURE ロトカル チャ ー ADDICTS fanzine, while ten years later, in 1998, Justin Sevakis decided to start an anime news website. Yes, 2008 marks both the 20th anniversary of Protoculture Addicts, and the 10th anniversary Issue #97 (July / August 2008) of Anime News Network. -

Graphic Novels & Trade Paperbacks

AUGUST 2008 GRAPHIC NOVELS & TRADE PAPERBACKS ITEM CODE TITLE PRICE AUG053316 1 WORLD MANGA VOL 1 TP £2.99 AUG053317 1 WORLD MANGA VOL 2 TP £2.99 SEP068078 100 BULLETS TP VOL 01 FIRST SHOT LAST CALL £6.50 FEB078229 100 BULLETS TP VOL 02 SPLIT SECOND CHANCE £9.99 MAR058150 100 BULLETS TP VOL 03 HANG UP ON THE HANG LOW £6.50 MAY058170 100 BULLETS TP VOL 04 FOREGONE TOMORROW £11.99 APR058054 100 BULLETS TP VOL 05 THE COUNTERFIFTH DETECTIVE (MR) £8.50 APR068251 100 BULLETS TP VOL 06 SIX FEET UNDER THE GUN £9.99 DEC048354 100 BULLETS TP VOL 07 SAMURAI £8.50 MAY050289 100 BULLETS TP VOL 08 THE HARD WAY (MR) £9.99 JAN060374 100 BULLETS TP VOL 09 STRYCHNINE LIVES (MR) £9.99 SEP060306 100 BULLETS TP VOL 10 DECAYED (MR) £9.99 MAY070233 100 BULLETS TP VOL 11 ONCE UPON A CRIME (MR) £8.50 STAR10512 100 BULLETS VOL 1 FIRST SHOT LAST CALL TP £6.50 JAN040032 100 PAINTINGS HC £9.99 JAN050367 100 PERCENT TP (MR) £16.99 DEC040302 1000 FACES TP VOL 01 (MR) £9.99 MAR063447 110 PER CENT GN £8.50 AUG052969 11TH CAT GN VOL 01 £7.50 NOV052978 11TH CAT GN VOL 02 £7.50 MAY063195 11TH CAT GN VOL 03 (RES) £7.50 AUG063347 11TH CAT GN VOL 04 £7.50 DEC060018 13TH SON WORSE THING WAITING TP £8.50 STAR19938 21 DOWN TP £12.99 JUN073692 24 NIGHTFALL TP £12.99 MAY061717 24 SEVEN GN VOL 01 £16.99 JUN071889 24 SEVEN GN VOL 02 £12.99 JAN073629 28 DAYS LATER THE AFTERMATH GN £11.99 JUN053035 30 DAYS OF NIGHT BLOODSUCKERS TALES HC VOL 01 (MR) £32.99 DEC042684 30 DAYS OF NIGHT HC (MR) £23.50 SEP042761 30 DAYS OF NIGHT RETURN TO BARROW HC (MR) £26.99 FEB073552 30 DAYS OF NIGHT -

ANIME FAN FEST PANELS SCHEDULE May 6-8, 2016

ANIME FAN FEST PANELS SCHEDULE May 6-8, 2016 MAY 6, FRIDAY CENTRAL CITY game given a bit of Japanese polish; players wager their Kingdom Hearts is one of the best-selling, and most 4:00pm - 5:00pm yen on their knowledge of a variety of tricky clues in their complex video game series of all time. In anticipation OTAKU USA’S ANIME WORTH WATCHING Now is probably quest to become Jeopardy! champion! of KHIII, we will be going over all aspects of the series the best time in history to be an anime fan. With tons 5:30pm- 6:30pm in great detail such as: elements of the plot, music, lore, of anime freely (and legally) available, the choices are BBANDAI NAMCO ENTERTAINMENT PRESENTS: ANIME and more. As well as discussing theories and specu- endless...which makes it all the more difficult for anime GAMES IN AMERICA Join Bandai Namco for a behind- lations about what is to come in the future. A highly fans to find out WHICH they should watch. Otaku USA the-scenes look at what it’s like working for the premier educational panel led by your host, Kyattan, this panel Magazine’s Daryl Surat (www.animeworldorder.com) Anime videogame publisher, the process and challenges is friendly to those who haven’t played every game, and NEVER accepts mediocrity as excellence and has prepared of bringing over anime-based and Japanese game content those who are confused about its plot. a selection of recommendations, as covered in the publi- to the Western market, and exclusive insider-only looks at 6:00pm- 7:00pm cation’s 9+ year history! Bandai Namco’s upcoming titles. -

Kana Ueda Hitoshi Sakimoto: Travis Creative Writing Life Behind the High School Q&A Composer Willingham: Music: Daoko Bebop Lounge (21+ Mixer) 9:45

LATE NIGHT EVENTS THURSDAY 5 PM 6 PM 7 PM 8 PM 9 PM 10 PM 11 PM Day & Time Room Event FRI 12:30am - 1:15am Highlands Locked Room Mystery Grand Panel Super Happy Fun Sale FRI 3:00am - 8:00am Kennessaw Graveyard Gaming 2017 6:00 SAT 12:00am - 2:00am Main Events Midnight Madness (18+) Michael S. SAT 12:30am - 1:30am CGC 103 Oh the Animated Horror (18+) Unplugged Kennesaw Funimation Party SAT 2:00am - 3:00am CGC 103 Wonderful World of Monster Girls (18+) 7:00 11:15 (18+) SAT 1:30am - 2:30am CGC 104 Diamonds in the Rough Belly Dancing State of the Fireside Chat Feodor Chin Littlekuriboh Historical SAT 12:15am - 2:45am CGC 105 Gunpla-jama Party Renaissance Waverly & Cobb Galleria Highlands Basics Manga Market N. Canna + Spotlight Unabridged Costuming 5:00 6:15 8:45 7:30 SAT 12:15am - 1:15am CGC 106 Video Game Hell (18+) 2017 K. Inoue 10:00 11:15 for Cosplay September 28 – October 1, 2017 SAT 12:15am - 2:45am Highlands Tentacles, WOW! (18+) FRIDAY 9 AM 10 AM 11 AM 12 PM 1 PM 2 PM 3 PM 4 PM 5 PM 6 PM 7 PM 8 PM 9 PM 10 PM 11 PM Bless4 Daoko Concert after midnight above for panels see Please Main Events Opening Ceremonies Nerdcore Live Concert ft Teddyloid Totally Lame Anime Anime Hell 4:00 6:30 5:15 8:00 10:00 12:00 Starlight Idol Festival 1000 Moonies Crunchyroll Fall Simulcast Grand Panel Audition Panel Pyramid Premiere Panel Funimation Peep Show (18+) 3:30 6:15 2:00 7:30 10:00 Pokemon History of Michael Voiceover Let’s Talk Jennifer Hale Young Academics Kennesaw Going, Japanese Sinterniklaas: Games AMA with Cosplay Gallery Yu-Gi-Oh with Critical -

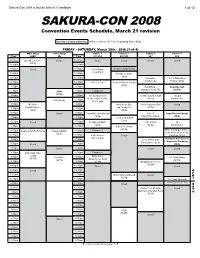

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

Wierzenia Z Perspektywy Estetyki Japońskiej. Mushishi Yuki Urushibary

Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis • No 3813 Literatura i Kultura Popularna XXIII, Wrocław 2017 DOI: 10.19195/0867-7441.23.7 Natalia Dmitruk Uniwersytet Wrocławski Wierzenia z perspektywy estetyki japońskiej. Mushishi Yuki Urushibary […] poczucie piękna wyrasta z realnego życia […] Tanizaki Junʼichirō, Pochwała cienia1 Słowa kluczowe: estetyka, Japonia, manga, shinto, animizm Keywords: aesthetic, Japan, manga, shinto, animism Yūjirō Nakamura, jeden z filozofów japońskich, w artykule Une Philosop- hie japonaise est-elle possible? stwierdził, że Japonia jest „kulturą przekładu”2. Rację jednak mają H. Gene Blocker i Christopher L. Starling, kiedy zauważają, że nie jest to przekład wierny, a zawsze subtelnie zmodyfikowany3. Zarówno Na- kamura, jak i Blocker oraz Starling w swoich rozważaniach tematem centralnym uczynili filozofię japońską, jednakże twierdzenia te można odnieść również do kultury Japonii jako zjawiska. Polska japonistka Beata Kubiak Ho-Chi w swo- jej książce Estetyka i sztuka japońska. Wybrane zagadnienia wielokrotnie zwra- ca uwagę na swoistą japońską otwartość na wpływy z zewnątrz — przy jedno- czesnym ich asymilowaniu i przetwarzaniu w celu stworzenia czegoś własnego i unikalnego4. Warto przypomnieć, że pierwsze kontakty z kulturą chińską miały miejsce już w epoce Yayoi (400 p.n.e.–250 n.e.), jednakże to okres pomiędzy VI/VII a IX w. n.e. jest najbardziej znaczący w wypadku wpływów kontynentu (przede wszystkim z Chin). Kontakt z Zachodem przypadał na restaurację Meiji 1 J. Tanizaki, Pochwała cienia, przeł. H. Lipszyc, Kraków 2016, s. 39. 2 Y. Nakamura, Une Philosophie japonaise est-elle possible?, „Ebisu” 1995, nr 8, s. 84, http:// www.persee.fr/doc/ebisu_1340-3656_1995_num_8_1_920 (dostęp: 10.07.2017). 3 H.G. Blocker, C.L. -

Corksligo Dublin Galway Limerick

CORK SLIGO DUBLIN GALWAY LIMERICK DUNDALK TIPPERARY WATERFORD CELEBRATING 10 YEARS WELCOME TO THE JAPANESE FILM FESTIVAL 2018 We are 10! 2018 marks a decade of The Embassy of Japan’s collaboration with Access>Cinema. The success in that time was not possible without various supporters, particularly the Ireland Japan Association and the Japan Foundation, and we look forward to working with existing and new supporters for 2018. We are really excited about this year’s line- up, which showcases the best of contemporary Japanese cinema, with a mix of new work from established directors and first features from inspiring new talent. Recently picking up the Japan Academy 2018 prizes for Best Film and Best Director, The Third Murder sees the great Hirokazu Kore-eda taking a break from his usual family dramas to deliver a dark legal thriller. Close Knit, the latest from Naoko Ogigami – her Rent-a-Cat was a favourite in 2013 – is a heartwarming yet poignant crowd- pleaser. Partially inspired by the life and work of Vincent van Gogh, The Sower is a quiet but probing story from new voice Yosuke Takeuchi. For this 10th edition our anime selection is particularly strong. We are honoured to welcome acclaimed screenwriter Mari Okada to Dublin for the Irish premiere of her debut feature Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, just weeks after its international premiere in Glasgow. On April 10th we present, for one night only, exclusive fan preview screenings of Studio Ponoc’s highly-anticipated first production Mary and the Witch’s Flower. We also present the latest films from Masaaki Yuasa.