Agricultural Resources and Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ims List Sanitation Compliance and Enforcement Ratings of Interstate Milk Shippers April 2017

IMS LIST SANITATION COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT RATINGS OF INTERSTATE MILK SHIPPERS APRIL 2017 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Rules For Inclusion In The IMS List Interstate milk shippers who have been certified by State Milk sanitation authorities as having attained the milk sanitation compliance ratings are indicated in the following list. These ratings are based on compliance with the requirements of the USPHS/FDA Grade A Pasteurized Milk Ordinance and Grade A Condensed and Dry Milk Products and Condensed and Dry Whey and were made in accordance with the procedures set forth in Methods of Making Sanitation Rating of Milk Supplies. *Proposal 301 that was passed at 2001 NCIMS conference held May 5-10, 2001, in Wichita, Kansas and concurred with by FDA states: "Transfer Stations, Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants must achieve a sanitation compliance rating of 90 or better in order to be eligible for a listing in the IMS List. Sanitation compliance rating scores for Transfer and Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants will not be printed in the IMS List". Therefore, the publication of a sanitation compliance rating score for Transfer and Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants will not be printed in this edition of the IMS List. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL LISTS WHICH HAVE BEEN ISSUED HERETOFORE ALL PRECEDING LISTS AND SUPPLEMENTS THERETO ARE VOID. The rules for inclusion in the list were formulated by the official representatives of those State milk sanitation agencies who have participated in the meetings of the National Conference of Interstate Milk Shipments. -

James E. Tillison, the Alliance of Western Milk Producers (Pdf)

,- tU. rllllldtlll~l ~ ~.elt:~l ft rlU||l, dllll IllllauIt I../l:ltl~.. II I"IId.UU~ lillll~., t. I t .3"t" r"lVl Page 2 of 5 USDA The Ilia n c e OALJ/HCO of Western Milk Procluoers ZOO0 JUL 11..4 I::9 U,: 22 July 14, 2000 RECEIVED Office of the Hearing Clerk USDA Room 1081, South Building, 1400 Independence Ave., S. W. Washington, D.C., 20250 SUBJECT: Milk in the Northeast and other Marketing Areas Docket No. AO-14-A69, et al., DA-003 Alexandria, Virginia May 8-12, 2000 Dear Sir: The Alliance of Westem Milk Producers is a trade association that represents two major operating cooperatives in Califomia -- California Dairies Inc. and Humboldt Creamery. These organizations represent nearly 50 percent of the milk and milk producers in California. Comments on the above federal order milk marketing hearing are being submitted on their behalf. While California is not part of the federal milk marketing system, what the federal system does has both direct and indirect impacts on California milk producers and the cooperatives they own. That is why the Alliance both attended the hearing and is now submitting this post-hearing brief on the proposals submitted prior to the hearing and the testimony given at the hearing. Butterfat value Several proposals were submitted to modify the value of butterfat in the price formulas under consideration at this hearing. The National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) and the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) both proposed lowering the value of butterfat. NMPF proposed reducing the Class IV blatterfat value by six cents a pound. -

The Marin-Sonoma Artisan Cheese Cluster by Carol A. Pranka a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction Of

Good as Gold: The Marin-Sonoma Artisan Cheese Cluster by Carol A. Pranka A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor J. Keith Gilless, Chair Professor Lynn Huntsinger Professor Nathan Sayre Spring 2014 © Carol A. Pranka 2014 Abstract Good as Gold: The Marin-Sonoma Artisan Cheese Cluster by Carol A. Pranka Doctor of Philosophy University of California, Berkeley Professor J. Keith Gilless, Chair The overall economic performance of rural communities across the United States is challenged by shifting patterns of production, consumption, and global competition. Recent research has identified clusters - geographically proximate group of interconnected companies and associated institutions in a particular field, linked by commonalities and complementaries - as a prominent feature of successful rural economies. This dissertation explores the emergence of an artisan cheese cluster from historic dairy roots in Marin and Sonoma Counties in the North Coast region of California. The artisan and farmstead cheese producers there provide an instructive case study to assess the social, cultural, and economic impacts of the artisan cheese clusters generally. Michael Porter’s (1990) “Diamond Model of Competitive Advantage” is utilized as an analytic framework to consider factors that provided competitive advantages during various historical periods before and during the emergence of the cluster, as well as to assess its current business environment. The viability of encouraging such artisan cheese clusters in other rural regions as an economic development strategy is evaluated based on these findings. -

HRBC Folder Front

BACK COVER LEGENDARY BEEF. LEGENDARY QUALITY. HARRIS RANCH BEEF COMPANY 16277 S. McCALL AVENUE, P.O. BOX 220, SELMA, CALIFORNIA 93662 www.harrisranchbeef.com (800) 742-1955 © HARRIS RANCH LEGENDARY BEEF. LEGENDARY QUALITY. LEGENDARY BEEF. LEGENDARY POCKET INSIDE FRONT COVER (Folder) Page 1 HARRIS RANCH AT A GLANCE Harris Farms was established in Fresno County, California, in 1937 by Jack and Teresa Harris. Today, Jack’s son, John, and his wife, Carole, oversee the 5 independent operating divisions of Harris Farms which is one of the largest employers in Fresno County with nearly 2,500 employees. Harris Ranch Divisions Harris Farms, Inc. Harris Ranch Beef Company Harris Feeding Company Harris Hospitality Division Harris Thoroughbred Horse Division Harris Farms Encompasses over 17,000 acres growing 35 different commodities. • Crops include: almonds, asparagus, grapes, pistachios and oranges as well as processing tomatoes, melons, garlic, onions, winter vegetables and organics. Harris Ranch Beef Company The processing and marketing arm of the beef division. • One of the largest fully integrated beef producers in the Western U.S.; we control all aspects of beef production including cattle sourcing, feeding and processing. • Unique “Partnership for Quality” program teams us with over 70 of the West’s most progressive ranching families to produce cattle to our quality specifications. • Established one of the first branded beef programs in the U.S. in 1982. • Retail, foodservice and export divisions. • Annual sales in excess of $400 million. • Expansive product line: fresh boxed beef, value-added ground beef, fresh seasoned beef and fully cooked beef entrées. • Beef production system: feed tested for pesticide residues, finished beef tested for antibiotic residues above USDA standards, cattle humanely and sustainably raised by Harris Ranch – Dr. -

1 Harris Ranch

HARRIS RANCH -- A COMMITMENT TO SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE 2020 Introduction At Harris Ranch, we believe that raising cattle and environmental stewardship go hand-in-hand. For us, as well as our ranching partners, the land is not just where we raise our cattle; it’s also where we raise our families. We have a personal stake in the quality of the environment and are always looking for ways to improve it. For those that raise cattle, sustainability means ensuring that the land will provide for the next generation by focusing not only on the well-being of our livestock, but also on maintaining the land and its natural resources. Sustainability, as it relates to farming and ranching, means growing crops and livestock in ways that meet three objectives: Environmental stewardship and resource conservation Improved well-being for the farm family and the community Economic profit In 1989 the American Society of Agronomy defined sustainable agriculture as follows: “A sustainable agriculture is one that, over the long term, enhances environmental quality and the resource base on which agriculture depends; provides for basic human food and fiber needs; is economically viable; and enhances the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole.” Harris Ranch believes that promoting sustainability in all of our agricultural operations is critical to our future and that of the agriculture industry. However, our dedication to the principle of sustainability can only be achieved through our additional commitment to the principles of quality, humane livestock handling and good corporate citizenship. A COMMITMENT TO QUALITY Over the past five decades, Harris Ranch has grown to be recognized as one of the most progressive, innovative and quality-conscious beef producers in the western United States. -

Organic Agriculture in Humboldt County, from Social Movement to Economic Development: Interviews with Organic Dairy and Row Crop Farmers

ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY, FROM SOCIAL MOVEMENT TO ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: INTERVIEWS WITH ORGANIC DAIRY AND ROW CROP FARMERS By Allyson L. Carroll A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Social Sciences August, 2006 ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY, FROM SOCIAL MOVEMENT TO ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: INTERVIEWS WITH ORGANIC DAIRY AND ROW CROP FARMERS By Allyson L. Carroll Approved by the Master's Thesis Committee: Judith Little, Major Professor Date Michael Smith, Committee Member Date Steven Hackett, Committee Member Date Selma Sonntag, Graduate Coordinator Date Christopher Hopper, Dean for Research and Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Organic agriculture is a concept that has evolved with its history, representing a farming method, social movement, and growing industry. Some analysts have critiqued organic agriculture as losing its grassroots soul and representing the conventional model of agriculture rather than an alternative to it. In order to ascertain current perceptions of organic agriculture from growers themselves, I interviewed 17 organic farmers in Humboldt County, California. These in-depth interviews focused on farmers’ rationale for certifying organic, values behind their farming style, associations with social movements, views of the federal regulations, and personal and regional economics. I interviewed both organic dairy and row crop farmers in order to compare groups and gain a spectrum of viewpoints. This study represents a place-based snapshot, particular to Humboldt County, California, a relatively rural and isolated area in need of viable economic development options. For the interviewed dairy farmers, organic agriculture represented a combination of an economic opportunity to maintain their multi-generational family farms combined with a farming method that reflected their existing techniques. -

BUY FRESH BUY LOCAL FOOD GUIDE Where to Find & Enjoy the Local Foods of Humboldt County

BUY FRESH BUY LOCAL FOOD GUIDE Where to find & enjoy the local foods of Humboldt County Known for its rural beauty, pristine beaches and magnificent redwoods, Humboldt County is also rich in local agriculture. Its broad and varied microclimates range from mild coastal regions to hot inland pockets, allowing for diverse, year-round agricultural production. Seasonal rains make for some of the best rangelands in the state, making cattle the foundation of niche markets in fine goat cheese, organic ice cream and sustainable grass-fed beef. Humboldt County retains a genuine farm culture due to the numerous small family-owned farms, many of them reaching back generations. Forward thinking residents and business owners proudly support local food and the many farmers’ markets. J J J This guide is designed to be your companion in discovering Humboldt County agriculture and to encourage you to buy fresh and buy local. The guide lists Humboldt County producers, farmers’ markets, CSAs, farm stands, U-picks, and food and farming organizations. Produced by the Community Alliance with Family Farmers, (CAFF) it is a brief introduction to food and farming on the North Coast; an overview of CAFF’s innovative programs; and an introduction to our Buy Fresh Buy Local campaign. All the information in this guide, and more, is available on CAFF’s Buy Fresh Buy Local website: wwwbuylocal.org or visit www.caff.org and click on the Buy Fresh Buy Local logo. Community Alliance with Family Farmers CAFF is building a movement of rural and urban people to foster family-scale agricul- ture that cares for the land, sustains local economies and promotes social justice. -

Humboldt County

HHUUMMBBOOLLDDTT CCOOUUNNTTYY AAGGRRIICCUULLTTUURREE SSUURRVVEEYY FFIINNAALL RREEPPOORRTT November 2003 Agricultural producers, landowners and the general public provide compelling insights and quantitative results on the importance of local agriculture to the economy, environment and quality of life in Humboldt County Sponsored by the Farm Bureau of Humboldt County and Humboldt State University Produced by Ben Morehead Department of Natural Resource Sciences Graduate Program, H.S.U. Humboldt County Agriculture Survey Final Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Gratitude to the sponsors of this survey, the Farm Bureau of Humboldt County and Humboldt State University for financing this project. This research could not have been done without the support and endorsement of the following agricultural groups and support organizations in Humboldt County. They provided mailing lists and encouraged their members to participate. The Creamery donated ice cream gift certificates for survey participants. • Farm Bureau of Humboldt County • Humboldt – Del Norte Cattlemen’s Association • Buckeye Conservancy • North Coast Growers Association • Humboldt Creamery Association • University of California Cooperative Extension Many thanks to the dozens of community members who reviewed and edited drafts of the surveys and provided feedback for this report. Thank you to the producers and the public who took the time to participate in this survey research. Thank you to all the agricultural producers of Humboldt County. Your efforts to protect and best use the land are appreciated. Stay strong for future generations. Ben Morehead, project director. November 2003 For additional information: Katherine Ziemer, Director Farm Bureau of Humboldt County 5601 South Broadway Eureka, CA 95503 707-443-4844 Report on the internet at: www.buckeyeconservancy.org Recommended Citation: Morehead, B. -

S the Beef? Costco’

Journal of Cleaner Production 278 (2021) 123744 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Cleaner Production journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro Where’s the beef? Costco’s meat supply chain and environmental justice in California * Sanaz Chamanara , 1, Benjamin Goldstein , Joshua P. Newell School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109, USA article info abstract Article history: Although the environmental and social burdens associated with the production of beef are well-un- Received 31 March 2020 derstood, due to supply chain complexities, we rarely know precisely where these impacts occur or who Received in revised form is affected. This limitation is a barrier to more sustainable production and consumption of animal 25 June 2020 products. In this study, we combine life cycle thinking with an environmental justice approach to map Accepted 12 August 2020 Costco’s beef supply chain in California and to explore the environmental burden of air pollution (PM ) Available online 22 August 2020 2.5 due to beef production in the San Joaquin Valley, a region that has some of the worst air quality in the Handling Editor: Yutao Wang United States. To map the supply chain of one of Costco’s primary suppliers, Harris Ranch, and the feedlots they operate, the study uses a methodological framework known as Tracking Corporations Keywords: Across Space and Time (TRACAST). Our modeling revealed that feedlots produce ~95% of total PM2.5 Livestock emissions across the beef supply chain, and they alone account for approximately 1/3 of total anthro- Environmental justice pogenic PM2.5 emissions in the Valley. -

Class Action Summary | Butter and Cheese Class Action This Is Not an Official Court Notice

dynamicsettlement.com 888.374.2033 Class Action Summary | Butter and Cheese Class Action This is not an official Court Notice. Information contained in this summary is subject to change. Case Overview: A $220 million settlement has been reached in a class action lawsuit brought against National Milk Producers Federation, Agri-Mark, Inc., Dairy Farmers of America, Inc., and Land O’Lakes, Inc. (collectively “Defendants”). The lawsuit claimed that an effort known as Cooperatives Working Together (CWT) operated a Herd Retirement Program that was a conspiracy to reduce milk output that violated the law. WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO PARTICIPATE IN THIS SETTLEMENT? Businesses and individual consumers in the United States that purchased butter and/or cheese directly from one or more of the CWT members including the Defendants, during the period from December 6, 2008 to July 31, 2013. Members of the CWT: Agri-Mark, Inc. Arkansas Dairy Associated Milk Producers Bongards Creameries Burke Milk Producers Cooperative Association Inc. Cooperative, Inc. California Dairies Inc. Cass-Clay Creamery Inc. Champlain Milk Producers Conesus Milk Producers Continental Dairy Products, Cooperative Cooperative Association, Inc. Inc. Cooperative Milk Producers Cortland Bulk Milk Dairy Farmers of America Dairylea Cooperative Inc. Dairymen's Marketing Association, Inc. Producers Cooperative Cooperative Inc. Ellsworth Cooperative Empire Keystone Farmers Cooperative First District Cooperative Foremost Farms USA Creamery Cooperative Creamery Association Humboldt Creamery Jefferson Bulk Milk Just Jersey Cooperative, Land O'Lakes, Inc. Lone Star Milk Producers Association Cooperative, Inc. Inc. Lowville Producers Dairy Magic Valley Quality Milk Manitowoc Milk Producers Maryland & Virginia Milk Massachusetts Coop. Milk Cooperative Producers, Inc. Cooperative Producers Cooperative Producers Fed. -

Handler List 2004 FINAL

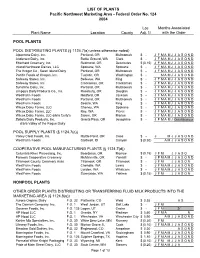

LIST OF PLANTS Pacific Northwest Marketing Area - Federal Order No. 124 2004 Loc Months Associated Plant Name Location County Adj. 1/ with the Order POOL PLANTS POOL DISTRIBUTING PLANTS (§ 1124.7(a) unless otherwise noted) Alpenrose Dairy, Inc. Portland, OR Multnomah $ - JFMAMJJASOND Andersen Dairy, Inc. Battle Ground, WA Clark $ - JFMAMJJASOND Eberhard Creamery, Inc. Redmond, OR Deschutes $ (0.15) JFMAMJJASOND Inland Northwest Dairies, LLC Spokane, WA Spokane $ - JFMAMJJASOND The Kroger Co., Swan Island Dairy Portland, OR Multnomah $ - JFMAMJJASOND Pacific Foods of Oregon, Inc. Tualatin, OR Washington$ - M A M J J A S O N D Safeway Stores, Inc. Bellevue, WA King $ - JFMAMJJASOND Safeway Stores, Inc. Clackamas, OR Clackamas $ - JFMAMJJASOND Sunshine Dairy, Inc. Portland, OR Multnomah $ - JFMAMJJASOND Umpqua Dairy Products Co., Inc. Roseburg, OR Douglas $ - JFMAMJJASOND WestFarm Foods Medford, OR Jackson $ - JFMAMJJASOND WestFarm Foods Portland, OR Multnomah $ - JFMAMJJASOND WestFarm Foods Seattle, WA King $ - JFMAMJJASOND Wilcox Dairy Farms, LLC Cheney, WA Spokane $ - JFMAMJJASOND Wilcox Dairy Farms, LLC Roy, WA Pierce $ - JFMAMJJASOND Wilcox Dairy Farms, LLC d/b/a Curly's Salem, OR Marion $ - JFMAMJJASOND Zottola Dairy Products, Inc. Grants Pass, OR Josephine $ - J F MA MJ Out of Business d/b/a Valley of the Rogue Dairy POOL SUPPLY PLANTS (§ 1124.7(c)) Valley Crest Foods, Inc. Myrtle Point, OR Coos $ - JMJJASOND WestFarm Foods Caldwell, ID Canyon $ (0.30) AMJ J ASOND COOPERATIVE POOL MANUFACTURING PLANTS (§ 1124.7(d)) Columbia River Processing, Inc. Boardman, OR Morrow $ (0.15) JFM JJASO Farmers Cooperative Creamery McMinnville, OR Yamhill $ - JFMAMJJASOND Tillamook County Creamery Assn. Tillamook, OR Tillamook $ - JFM JJASON WestFarm Foods Chehalis, WA Lewis $ - JFMAMJJASOND WestFarm Foods Lynden, WA Whatcom $ - JFMAMJJASOND WestFarm Foods Sunnyside, WA Yakima $ (0.15) JFM JJASON NONPOOL PLANTS OTHER ORDER PLANTS DISTRIBUTING OR TRANSFERRING FLUID MILK PRODUCTS INTO THE MARKETING AREA (§ 1124.8(a)) Aurora Organic Dairy F.O. -

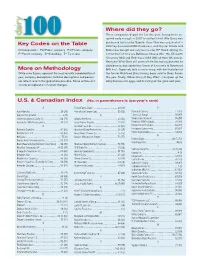

Key Codes on the Table More on Methodology Where Did They

Where did they go? Three companies depart the list this year, having been ac- quired early enough in 2007 to not be listed. Alto Dairy was Key Codes on the Table purchased last year by Saputo, Cass Clay was acquired at in 2007 by Associated Milk Producers, and Crystal Cream and C=Cooperative Pu=Public company Pr=Private company Butter was bought out early last year by HP Hood. Joining the P=Parent company S=Subsidiary T= Tie in rank list for the first time are BelGioso Cheese (No. 75), Ellsworth Creamery (84) and Roth Kase USA (96) all from Wisconsin. Next year Winn-Dixie will come off the list, having divested its dairy processing capabilities (some of it recently to Southeast More on Methodology Milk Inc.). Supervalu tells a similar story, with the final plant of While sales figures represent the most recently completed fiscal the former Richfood Dairy having been sold to Dean Foods year, company descriptions, facilities descriptions and person- this year. Finally, Wilcox Dairy of Roy, Wash., has given up the nel reflect recent changed where possible. Some entries will dairy business for eggs, and its listing will be gone next year. include an explanation of recent changes. U.S. & Canadian Index (No. in parentheses is last year’s rank) A Foster Farms Dairy ....................................... 50 (48) P Agri-Mark Inc. .............................................. 29 (29) Friendly Ice Cream Corp. ...............................55 (56) Parmalat Canada .........................................12 (13) Agropur Cooperative .........................................6 (9) G Perry’s Ice Cream ........................................ 97 (97) Anderson Erickson Dairy Co. ......................... 66 (71) Glanbia Foods Inc. ........................................ 23 (32) Plains Dairy Products ....................................95 (99) Associated Milk Producers Inc.