Bernard Nussbaum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuity Within Change: the German-American Foreign and Security Relationship During President Clinton’S First Term”

“Continuity within Change: The German-American Foreign and Security Relationship during President Clinton’s First Term” Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. bei dem Fachbereich Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Thorsten Klaßen Berlin 2008 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Eberhard Sandschneider Zweitgutachter: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Peter Rudolf Datum der Disputation: 10.12.2008 2 Table of Contents Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7 A Note on Sources .................................................................................................................... 12 I. The United States After the End of the Cold War ................................................................ 13 I.1. Looking for the Next Paradigm: Theoretical Considerations in the 1990s.................... 13 I.1.1 The End of History ................................................................................................... 13 I.1.2 The Clash of Civilizations ....................................................................................... 15 I.1.3 Bipolar, Multipolar, Unipolar? ................................................................................ 17 I.2. The U.S. Strategic Debate ............................................................................................. -

HILLARY's SECRET WAR the CLINTON CONSPIRACY to MUZZLE INTERNET JOURNALISTS

* HILLARY'S SECRET WAR THE CLINTON CONSPIRACY to MUZZLE INTERNET JOURNALISTS. RICHARD POE Copyright (c) 2004 by Richard Poe. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other - except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by WND Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. Poe, Richard, 1958-. Hillary's Secret War : The Clinton Conspiracy To Muzzle Internet Journalism / Richard Poe. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7852-6013-7 Printed in the United States of America 04 05 06 07 08 QW 5432. To my wife Marie. CONTENTS. Foreword. Preface. Introduction. 1. Through the Looking Glass. 2. Hillary's Shadow Team. 3. Why Hillary Fears the Internet. 4. Hillary's Power. 5. Web Underground. 6. The Clinton Body Count. 7. Hillary's Enemy List. 8. The Drudge Factor. 9. The Chinagate Horror. 10. SlapHillary.com. 11. The Drudge Wars. 12. Angel in the Whirlwind. Epilogue A Time for Heroes. In Memory of Barbara Olson. FOREWORD. BY JIM ROBINSON. HILLARY'S SECRET WAR by Richard Poe is the first book I've read that really pulls together the story of the Internet underground during the Clinton years. I was thrilled to read it. This story has never been told before, and I'm proud to say that I was part of it, in my own small way. We poured a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into building FreeRepublic.com and organizing a cyber- community of tens of thousands of Freeper activists all over the United States. -

White House Compliance with Committee Subpoenas Hearings

WHITE HOUSE COMPLIANCE WITH COMMITTEE SUBPOENAS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 6 AND 7, 1997 Serial No. 105–61 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45–405 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 08:13 May 28, 2003 Jkt 085679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HEARINGS\45405 45405 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEPHEN HORN, California THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia DC DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ROD R. BLAGOJEVICH, Illinois STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois MARSHALL ‘‘MARK’’ SANFORD, South JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts Carolina JIM TURNER, Texas JOHN E. -

Special Counsels, Independent Counsels, and Special Prosecutors: Options for Independent Executive Investigations Name Redacted Legislative Attorney

Special Counsels, Independent Counsels, and Special Prosecutors: Options for Independent Executive Investigations name redacted Legislative Attorney June 1, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44857 Special Counsels, Independent Counsels, and Special Prosecutors Summary Under the Constitution, Congress has no direct role in federal law enforcement and its ability to initiate appointments of any prosecutors to address alleged wrongdoings by executive officials is limited. While Congress retains broad oversight and investigatory powers under Article I of the Constitution, criminal investigations and prosecutions have generally been viewed as a core executive function and a responsibility of the executive branch. Historically, however, because of the potential conflicts of interest that may arise when the executive branch investigates itself (e.g., the Watergate investigation), there have been calls for an independently led inquiry to determine whether officials have violated criminal law. In response, Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) have used both statutory and regulatory mechanisms to establish a process for such inquiries. These responses have attempted, in different ways, to balance the competing goals of independence and accountability with respect to inquiries of executive branch officials. Under the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, Congress authorized the appointment of “special prosecutors,” who later were known as “independent counsels.” Under this statutory scheme, the Attorney General could request that a specially appointed three-judge panel appoint an outside individual to investigate and prosecute alleged violations of criminal law. These individuals were vested with “full power and independent authority to exercise all investigative and prosecutorial functions and powers of the Department of Justice” with respect to matters within their jurisdiction. -

RLB Letterhead

6-25-14 White Paper in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request re the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents. This is a White Paper (WP) in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ, cv 02-6788 (Seybert, J), plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request. The plaintiff sought the release of the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents by application of President Obama’s December 29, 2009 E.O. 13526, Classified National Security Information, 75 F.R. 707 (January 5, 2010), § 3.5 Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR). On June 2, 2014, President Reagan Library Archivist/FOIA Coordinator Shelly Williams rendered a Case #M-425 denial decision with an attached Worksheet: This is in further response to your request for your Mandatory Review request for release of information under the provisions of Section 3.5 of Executive Order 13526, to Reagan Presidential records pertaining to Ross Perot doc re report see email. These records were processed in accordance with the Presidential Records Act (PRA), 44 U.S.C. §§ 2201-2207. Id. Emphasis added. The Worksheet attachment to the decision lists three sets of Keisler, Peter: Files with Doc ## 27191, 27192, and 27193 notations. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CARA LESLIE ALEXANDER, ) et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil No. 96-2123 ) 97-1288 ) (RCL) FEDERAL BUREAU OF ) INVESTIGATION, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter comes before the court on Plaintiffs’ Motion [827] to Compel Answers to Plaintiffs’ First Set of Interrogatories to the Executive Office of the President Pursuant to Court Order of April 13, 1998. Upon consideration of this motion, and the opposition and reply thereto, the court will GRANT the plaintiffs’ motion. I. Background The underlying allegations in this case arise from what has become popularly known as “Filegate.” Plaintiffs allege that their privacy interests were violated when the FBI improperly handed over to the White House hundreds of FBI files of former political appointees and government employees from the Reagan and Bush Administrations. This particular dispute revolves around interrogatories pertaining to Mike McCurry, Ann Lewis, Rahm Emanuel, Sidney Blumenthal and Bruce Lindsey. Plaintiffs served these interrogatories pertaining to these five current or former officials on May 13, 1999. The EOP responded on July 16, 1999. Plaintiffs now seek to compel further answers to the following lines of questioning: 1. Any and all knowledge these officials have, including any meetings held or other communications made, about the obtaining of the FBI files of former White House Travel Office employees Billy Ray Dale, John Dreylinger, Barney Brasseux, Ralph Maughan, Robert Van Eimerren, and John McSweeney (Interrogatories 11, 35, 40 and 47). 2. Any and all knowledge these officials have, including any meetings held or other communications made, about the release or use of any documents between Kathleen Willey and President Clinton or his aides, or documents relating to telephone calls or visits 2 between Willey and the President or his aides (Interrogatories 15, 37, and 42). -

Whitewater Scandal Essential Question: What Was the Whitewater Scandal About? How Did It Change Arkansas? Guiding Question and Objectives

Lesson Plan #4 Arkansas History Whitewater Scandal Essential Question: What was the Whitewater Scandal about? How did it change Arkansas? Guiding Question and Objectives: 1. Explain the impact of the Whitewater Scandal and how this effected the public and the people involved. 2. How do politicians and the politics make an impact on the world? 3. Is there an ethical way to deal with a scandal? NCSS strands I. Culture II. Time, Continuity, and Change III. People, Places, and Environments IV. Individual Development and Identity V. Individuals, Groups, and Institutions AR Curriculum Frameworks: PD.5.C.3 Evaluate various influences on political parties during the electoral process (e.g., interest groups, lobbyists, Political Action Committees [PACs], major events) Teacher Background information: The Whitewater controversy (also known as the Whitewater scandal, or simply Whitewater) began with an investigation into the real estate investments of Bill and Hillary Clinton and their associates, Jim and Susan McDougal, in the Whitewater Development Corporation, a failed business venture in the 1970s and 1980s. — http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/ encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=4061 Materials needed: The Whitewater Scandal reading —see handout Assessment —see handout Opening activity: Ask what the Whitewater Scandal might be? Plot information on the board and guide the students into the direction of the Bill Clinton’s presidency. Activities: 7 minutes—Discuss and determine what the Whitewater Scandal might be. 25 minutes—Read the handout, take notes, and discuss materials while displaying the information opposed to strict lecturing. 30 minutes—Complete the assessment and have students share their findings. 28 minutes—Students will discuss their findings and discuss their impressions of the scandal. -

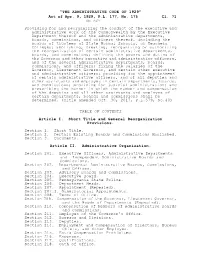

THE ADMINISTRATIVE CODE of 1929" Act of Apr

"THE ADMINISTRATIVE CODE OF 1929" Act of Apr. 9, 1929, P.L. 177, No. 175 Cl. 71 AN ACT Providing for and reorganizing the conduct of the executive and administrative work of the Commonwealth by the Executive Department thereof and the administrative departments, boards, commissions, and officers thereof, including the boards of trustees of State Normal Schools, or Teachers Colleges; abolishing, creating, reorganizing or authorizing the reorganization of certain administrative departments, boards, and commissions; defining the powers and duties of the Governor and other executive and administrative officers, and of the several administrative departments, boards, commissions, and officers; fixing the salaries of the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and certain other executive and administrative officers; providing for the appointment of certain administrative officers, and of all deputies and other assistants and employes in certain departments, boards, and commissions; providing for judicial administration; and prescribing the manner in which the number and compensation of the deputies and all other assistants and employes of certain departments, boards and commissions shall be determined. (Title amended Oct. 30, 2017, P.L.379, No.40) TABLE OF CONTENTS Article I. Short Title and General Reorganization Provisions. Section 1. Short Title. Section 2. Certain Existing Boards and Commissions Abolished. Section 3. Documents. Article II. Administrative Organization. Section 201. Executive Officers, Administrative Departments and Independent Administrative Boards and Commissions. Section 202. Departmental Administrative Boards, Commissions, and Offices. Section 203. Advisory Boards and Commissions. Section 204. Executive Board. Section 205. Pennsylvania State Police. Section 206. Department Heads. Section 207. Appointment (Repealed). Section 207.1. Gubernatorial Appointments. Section 208. Terms of Office. -

The Keep Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 1996 Press Releases 4-4-1996 04/04/1996 - Zeifman To Offer New Theories About Watergate Scandal.pdf University Marketing and Communications Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/press_releases_1996 Recommended Citation University Marketing and Communications, "04/04/1996 - Zeifman To Offer New Theories About Watergate Scandal.pdf" (1996). 1996. 93. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/press_releases_1996/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Press Releases at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1996 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 96-100 April 4, 1996 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: ZEIFMAN TO OFFER NEW THEORIES ABOUT WATERGATE SCANDAL CHARLESTON -- Theories and observations about what really took place in Washington during the Richard Nixon impeachment proceedings will be the topic of a public presentation by former House Judiciary Committee chief counsel Jerry Zeifman at 3 p.m. Monday in Eastern Illinois University's Coleman Hall Auditorium. During his talk, Zeifman will share information from his recently published book, "Without Honor: The Impeachment of President Nixon and the Crimes of Camelot," which gives a personal account of the judiciary process using first-hand material from November 1973 through August 1974 to show how the historic impeachment inquiry was tainted. Zeifman's book is based primarily on an 800-page diary he kept at the time, describing the actions, ethical and otherwise, of key impeachment figures such as Nixon; John Doar, special counsel to the inquiry and formerly a key figure in Robert Kennedy's Justice Department; and Doar aide Hillary Rod ham (now the First Lady) and her fellow staffer Bernard Nussbaum, who recently resigned as President Clinton's -more- ADD 1/1/1/1 ZEIFMAN chief White House counsel. -

The Clinton Administration and the Erosion of Executive Privilege Jonathan Turley

Maryland Law Review Volume 60 | Issue 1 Article 11 Paradise Losts: the Clinton Administration and the Erosion of Executive Privilege Jonathan Turley Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan Turley, Paradise Losts: the Clinton Administration and the Erosion of Executive Privilege, 60 Md. L. Rev. 205 (2001) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol60/iss1/11 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADISE LOST: THE CLINTON ADMINISTRATION AND THE EROSION OF EXECUTIVE PRIVILEGE JONATHAN TuRLEY* INTRODUCTION In Paradise Lost, Milton once described a "Serbonian Bog ... [w]here Armies whole have sunk."' This illusion could have easily been taken from the immediate aftermath of the Clinton crisis. On a myriad of different fronts, the Clinton defense teams advanced sweep- ing executive privilege arguments, only to be defeated in a series of judicial opinions. This "Serbonian Bog" ultimately proved to be the greatest factor in undoing efforts to combat inquiries into the Presi- dent's conduct in the Lewinsky affair and the collateral scandals.2 More importantly, it proved to be the undoing of years of effort to protect executive privilege from risky assertions or judicial tests.' In the course of the Clinton litigation, courts imposed a series of new * J.B. & Maurice C. -

The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Independent Counsel Statute: Toward Depoliticization

Volume 102 Issue 1 Article 5 September 1999 The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Independent Counsel Statute: Toward Depoliticization Marjorie Cohn Thomas Jefferson School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Courts Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Marjorie Cohn, The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Independent Counsel Statute: Toward Depoliticization, 102 W. Va. L. Rev. (1999). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol102/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cohn: The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Inde THE POLITICS OF THE CLINTON IMPEACHMENT AND THE DEATH OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL STATUTE: TOWARD DEPOLITICIZATION Marjorie Cohn I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................59 II. THE ANDREW JOHNSON IMPEACHMENT ..................................60 III. TE LEGACY OF WATERGATE .................................................60 IV. THE POLITICAL APPOINTMENT OF AN "INDEPENDENT COUNSEL"... ..............................................................................................63 V. STARR'S W AR ..........................................................................66 -

The Specially Investigated President

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1998 The pS ecially Investigated President Charles Tiefer University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the National Security Law Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation The peS cially Investigated President, 5 U. Chi. L. Sch. Roundtable 143 (1998) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES The Specially Investigated President CHARLES TIEFER t 1. Introduction For the past decade a series of long-term investigations by Independent Counselsl occurred in parallel with those of special congressional committees.2 These investigations have resulted in the imposition of a new legal status for the president. This new status re-orients the long-standing tension that exists between the bounds of presidential power and the president's vulnerability to legal suit.3 The parallel special inquiries into the subjects of Iran-Contra, t. Charles Tiefer is Associate Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore School of Law. He served as Solicitor and Deputy General Counsel for the House .of Represen tatives from 1984 to 1995. He received his J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1977 and his B.A. from Columbia University in 1974.