Chapter Two Φφφ Historical Background to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

SINGING PSALMS with OWLS: a VENDA 20Th CENTURY MUSICAL HISTORY Part Two: TSHIKONA, BEER SONGS and Personal SONGS

36 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY OF AFRICAN MUSIC SINGING PSALMS WITH OWLS: A VENDA 20th CENTURY MUSICAL HISTORY pART TwO: TSHIKONA, BEER SONGS AND pERSONAL SONGS by JACO KRUGER The three categories of Venda music discussed here are tshikona (the bamboo pipe dance), beer songs (malende, jive) and personal songs. As I indicate in part One of this essay,1 tshikona is useful for the construction of a musical history because its performance is intimately associated with traditional politics. By contrast, beer songs do not feature di rectly in politics. However, they not only comprise the largest category of adult music, they also have more elaborate texts than Venda music forms such as tshikona or tshigombela. While song texts have an important function, they arguably play a secondary role in large scale performances of communal dance music such as tshigombela and tshikona, which primarily are geared towards emotional arousal through sound and movement. As the continuum of musical performance extends towards smaller groups, and finally the individual musician, performances become more reflective, and their cognitive content increases to a point where a simple accompaniment on a musical bow or guitar becomes the subservient carrier of song texts of epic proportion (see Kruger 1993:348-403). While the study of large-scale dance performance reveals general social developments, the texts of beer songs and personal songs not only uncover the detail of these develop ments but also the emotional motivations which underpin them. Tshikona Tshikona is one of a number of South African pipe dances (see Kirby 1968:135 170). These dances mostly take place under the auspices of traditional leaders, and they are associated with important social rituals. -

A Short Chronicle of Warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau* Khoisan Wars tween whites, Khoikhoi and slaves on the one side and the nomadic San hunters on the other Khoisan is the collective name for the South Afri- which was to last for almost 200 years. In gen- can people known as Hottentots and Bushmen. eral actions consisted of raids on cattle by the It is compounded from the first part of Khoi San and of punitive commandos which aimed at Khoin (men of men) as the Hottentots called nothing short of the extermination of the San themselves, and San, the names given by the themselves. On both sides the fighting was ruth- Hottentots to the Bushmen. The Hottentots and less and extremely destructive of both life and Bushmen were the first natives Dutch colonist property. encountered in South Africa. Both had a relative low cultural development and may therefore be During 18th century the threat increased to such grouped. The Colonists fought two wars against an extent that the Government had to reissue the the Hottentots while the struggle against the defence-system. Commandos were sent out and Bushmen was manned by casual ranks on the eventually the Bushmen threat was overcome. colonist farms. The Frontier War (1779-1878) The KhoiKhoi Wars This term is used to cover the nine so-called "Kaffir Wars" which took place on the eastern 1st Khoikhoi War (1659-1660) border of the Cape between the Cape govern- This was the first violent reaction of the Khoikhoi ment and the Xhosa. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

The Nature of Medicine in South Africa: the Intersection of Indigenous and Biomedicine

THE NATURE OF MEDICINE IN SOUTH AFRICA: THE INTERSECTION OF INDIGENOUS AND BIOMEDICINE By Kristina Monroe Bishop __________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY AND DEVELOPMENT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN GEOGRAPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kristina Monroe Bishop entitled The Nature of Medicine in South Africa: The Intersection of Indigenous and Biomedicine and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 Paul Robbins _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 John Paul Jones III _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 Sarah Moore _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 Ivy Pike Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. ________________________________________________ Date: May 7, 2010 Dissertation Director: Paul Robbins 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrower under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted from the author. -

Clergy's Resistance to VENDA Homeland's INDEPENDENCE in the 1970S and 1980S

CLERGY’S Resistance to VENDA HOMELAND’S INDEPENDENCE IN THE 1970S and 1980S S.T. Kgatla Research Institute for Theology and Religion University of South Africa [email protected] ABSTRACT The article discusses the clergy’s role in the struggle against Venda’s “independence” in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as resistance to the apartheid policy of “separate development” for Venda. It also explores the policy of indirect white rule through the replacement of real community leaders with incompetent, easily manipulated traditional chiefs. The imposition of the system triggered resistance among the youth and the churches, which led to bloody reprisals by the authorities. Countless were detained under apartheid laws permitting detention without trial for 90 days. Many died in detention, but those responsible were acquitted by the courts of law in the Homeland. The article highlights the contributions of the Black Consciousness Movement, the Black People Conversion Movement, and the Student Christian Movement. The Venda student uprising was second in magnitude only to the Soweto uprising of 16 June 1976. The torture of ministers in detention and the response by church leaders locally and internationally, are discussed. The authorities attempted to divide the Lutheran Church and nationalise the Lutherans in Venda, but this move was thwarted. venda was officially re-incorporated into South Africa on 27 April 1994. Keywords: Independence; resistance; churches; struggle; Venda Homeland university of south africa Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/2016/1167 Volume 42 | Number 3 | 2016 | pp. 121–141 Print ISSN 1017-0499 | Online 2412-4265 https://upjournals.co.za/index.php/SHE © 2017. -

I OTET POLITICAL REPORT Adopted by the National

I OTET POLITICAL REPORT adopted by the National Committee on 8 September 1990 Introduction 1 Namibia 1 Front Line States 2 UnitedOppositiontoApartheid 2 ThecrisisinNatalandtheroleofInkatha 4 The end of the white monolith 5 Theinternationaldimensiontothecrisisofapartheid 5 The"peaceprocess" 6 Futureperspectivesfor Britishandinternational policy 7 The tasks of the Anti-ApartheidMovement 8 TheWayAhead 8 SOUTH AFRICA NelsonMandelaInternationalReceptionCommittee 10 Nelson Mandela Reception Committee - Britain 11 Sanctions 14 South Africa -FreedomNow!campaign 15 NAMIBIA / FRONT LINE STATES 18 CAMPAIGNS Economiccollaboration 19 Military/nuclearcollaboration 22 Sports boycott 23 Culturalandacademicboycotts 24 SouthernAfricaTheImprisonedSociety(SATIS) 24 International work 29 AREAS OF WORK TradeUnions 31 LocalGroups 33 LocalAuthorities 36 Students and youth 37 Women 37 Blackandethnicminorities 38 Health 38 Multi-faith 39 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH Anti-ApartheidNews 39 Research and publications 40 Pressandmedia 40 FINANCE AND FUND-RAISING 41 ORGANISATION Membership 43 AGM/NationalCommittee/ExecutiveCommittee 44 Office/staff 45 POLITICAL REPORT Adopted by the National Committee on 8 September 1990. Introduction THE ANTI-APARTHEID MOVEMENT THE WAY AHEAD 1990 has proved to be a turning point in the history of the struggle for freedom in Southern Africa. Within a period of a little over three months from February to May - Namibia gained its independence under a democratically elected SWAPO government; the African National Congress, Pan Africanist Congress -

EB145 Opt.Pdf

E EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a FREE SOUTHERN AFRICA 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 C (212) 4n-0066 FAX: (212) 979-1013 S A #145 21 february 1994 _SU_N_D_AY-.::..:20--:FEB:.=:..:;R..:..:U..:..:AR:..:.Y:.....:..:.1994::...::.-_---.". ----'-__THE OBSERVER_ Ten weeks before South Africa's elections, a race war looks increasingly likely, reports Phillip van Niekerk in Johannesburg TOKYO SEXWALE, the Afri In S'tanderton, in the Eastern candidate for the premiership of At the meeting in the Pretoria Many leading Inkatha mem can National Congress candidate Transvaal, the white town coun Natal. There is little doubt that showgrounds three weeks ago, bers have publicly and privately for the office of premier in the cillast Wednesday declared itself Natal will fall to the ANC on 27 when General Constand Viljoen, expressed their dissatisfaction at Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Veree part of an independent Boer April, which explains Buthelezi's head ofthe Afrikaner Volksfront, Inkatha's refusal to participate in niging province, returned shaken state, almost provoking a racial determination to wriggle out of was shouted down while advo the election, and could break from a tour of the civil war in conflagration which, for all the having to fight the dection.~ cating the route to a volkstaat not away. Angola last Thursday. 'I have violence of recent years, the At the very least, last week's very different to that announced But the real prize in Natal is seen the furure according to the country not yet experienced. concessions removed any trace of by Mandela last week, the im Goodwill Zwelithini, the Zulu right wing,' he said, vividly de The council's declaration pro a legitimate gripe against the new pression was created that the king and Buthelezi's nephew. -

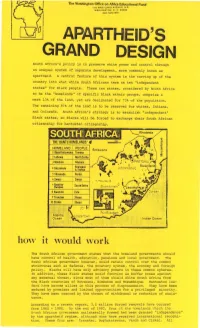

Apartheid's Grand Design

The Washington Office on Africa Educational Fund 110 MARYLAND AVENUE. N .E. WASHINGTON. 0. C. 20002 (202) 546-7961 APARTHEID'S GRAND DESIGN South Africa's policy is to preserve white power and control through an unequal system of separate development, more commonly known as apartheid. A central feature of this system is the carving up of the country into what white South Africans term as ten "independent states" for Black people. These ten states, considered by South Africa to be the "homelands" of specific Black ethnic groups, comprise a mere 13% of the land, yet are designated for 73% of the population. The remaining 87% of the land is to be reserved for whites, Indians, and Coloreds. South Africa's strategy is to establish "independent" Black states, so Blacks will be forced to exchange their South African citizenship for bantustan citizenship. THE 'BANTU HOMELANDS' 4 HOMELAND I PEOPLE I Boputhatswanai Tswana 2 lebowa I North Sotho -~ Hdebete Ndebe!e 0 Shangaan Joh<tnnesourg ~ Gazankulu & Tsonga 5 Vhavenda Venda --~------l _ ______6 Swazi 1 1 ___Swazi_ _ _ '7 Basotho . Qwaqwa South Sotho 8 Kwazulu 9 Transkei 10 Ciskei It• vvould w-ork The South African government states that the homeland governments should have control of health, education, pensions and local government. The South African government however, would retain control over t h e common structures such as defense, the monetary s y stem, the economy and foreign policy . Blacks wi ll have only advisory powers in these common spheres. In addition, these Black states would function as buffer zones against any external threat, since most of them shield white South Africa from the Black countries of Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. -

Committed to Unity

Committed to Unity: South Africa’s Adherence to Its 1994 Political Settlement Paul Graham IPS Paper 6 Abstract This paper reviews the commitment of the remaining power contenders and other political actors to the settlement which was reached between 1993 and 1996. Based on interviews with three key actors now in opposing political parties represented in the National Assembly, the paper makes the case for a continued commitment to, and consensus on, the ideals and principles of the 1996 Constitution. It provides evidence of schisms in the dominant power contender (the African National Congress) which have not led to a return in political violence post-settlement. The paper makes the point that, while some of this was the result of President Nelson Mandela’s presence, more must be ascribed to the constitutional arrangements and commitments of the primary political actors and the citizens of South Africa. © Berghof Foundation Operations GmbH – CINEP/PPP 2014. All rights reserved. About the Publication This paper is one of four case study reports on South Africa produced in the course of the collaborative research project ‘Avoiding Conflict Relapse through Inclusive Political Settlements and State-building after Intra-State War’, running from February 2013 to February 2015. This project aims to examine the conditions for inclusive political settlements following protracted armed conflicts, with a specific focus on former armed power contenders turned state actors. It also aims to inform national and international practitioners and policy-makers on effective practices for enhancing participation, representation, and responsiveness in post-war state-building and governance. It is carried out in cooperation with the partner institutions CINEP/PPP (Colombia, Project Coordinators), Berghof Foundation (Germany, Project Research Coordinators), FLACSO (El Salvador), In Transformation Initiative (South Africa), Sudd Institute (South Sudan), Aceh Policy Institute (Aceh/Indonesia), and Friends for Peace (Nepal). -

South Africa Fact Sheet

Souher Afrc Pesecie 1/88 South Africa Fact Sheet Thirty-four million people live in South Africa today, yet only 4.9 million whites have full rights of citizenship. The Black population of 28 million has no political power and is subject to strict government controls on where to live, work, attend school, be born and be buried. This Is the apartheid system which produces enormous wealth for the white minority and grinding poverty for millions of Black South Africans. Such oppression has fueled a rising challenge to white minority rule in the 1980's through strikes, boycotts, massive demonstrations and stayaways. International pressure on the white minority government has also been growing. In response, the government has modified a few existing apartheid laws without eliminating the basic structure of apartheid. This so called reform program has done nothing to satisfy Black South Africans' demands for majority rule in a united, democratic and nonracial South Africa. Struggling to reassert control, the government has declared successive states of emergency and unleashed intensive repression, seeking to conceal its actions by a media blackout, press censorship and continuing propaganda about change. As part of its "total strategy" to preserve white power, Pretoria has also waged war against neighboring African states in an effort to end their support for the anti-apartheid struggle and undermine regional efforts to break dependence on the apartheid economy. This Fact Sheet is designed to get behind the white government's propaganda shield and present an accurate picture of apartheid's continuing impact on the lives of millions of Blacks In southern Africa.