Translating Texts Into Art: Specimens from the Jaina Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mable Ringling Museum of Art

INDIAN SCULPTURE IN THE MABLE RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART by R oy C. Cra ven, Jr. INDIAN SCULPTURE IN THE J OHN AND MABL E RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART by R oy C. Craven , J r. Un iversity o f Flo rida Mo n o graph s HUMANITIES i NO . 6, W n ter 1961 DA UNIVERS ITY OF FLORIDA PRESS GAIN SVILLE , FLORI E ’ EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Huma nities Monog raphs T . W TE HE B E T Chairman AL R R R , Profes sor of English CLIN T ON ADAM S Professor of Art H M C ARLES W . ORRIS Professor of Philosophy C A. R BE T . O R SON Profe ssor of Engli sh Associate Professor of German PY GH T 1961 BY THE B D OF CO RI , , OAR COM M ISSIONERS OF ST ATE INSTI T U TI ONS OF FLORIDA L IBRARY OF CONGRESS D 61-63517 CATALOGU E CAR NO . PRINTED BY THE BU LKLEY -NEWM AN PRINTING COM PANY PREFACE In 1956 a group of Indian sculptures was placed on display in the loggia of the John e e sev and M able Ringling Mus eum of Art . Th s o n n enteen works were purchas ed by Mr. J h Ri g ling in the thirties at the clos e of his collecting ’ areer and t en la en in the e c , h y hidd mus um s r r ecor basem ent for some thi ty yea s . R ds which could tell of how and where these sculptures ere o ta ne a e een o t but the fa t t at w b i d h v b l s , c h they constitute a rich gift to the people of Flori a da is apparent in the works thems elves . -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

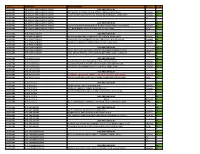

Location PLATETITLE SIXTYCHARNAME Source Count GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 1993 PRATISHTHA by GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DRS

Location PLATETITLE SIXTYCHARNAME Source Count GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 1993 PRATISHTHA BY GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DRS. DEEPAK & HIMANI DALIA & ANOKHI, NIRALI & ANERI DALIA Previous 57 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI SATISH-KINNARY,AAKASH-PURVA-RIYAAN-NAIYOMI,BADAL-SONIA SHAH Previous 59 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI NA 0 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 0 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI VAIDYA RAMANBEN BHAKKAMBHAI TUSHAR DIMPLE HEMLATA PRABODH Gheeboli 57 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DR. CHANDRAKANT PRANLAL SHAH AND DEVYANI SHAH Raffle 46 0 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH DR.RASHMI DIPCHAND, CHANDRIKA, RAJU, MONA, HITEN GARDI Previous 54 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH KERNEL,CHETNA,RAJA,MEENA,ASHISH,AMI,SHAILEE & SUJAL PARIKH Previous 58 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH NAGINDAS-VIJKORBEN, ARVIND-KIRAN, MANISH, ALKA SHAH Previous 51 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 0 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH ANISH, ANJALI, DULARI PARAG, MEMORY OF SHARDA MAFATLAL DOSHI Gheeboli 60 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH JYOTI PRADIP GRISHMA JUGNU SANYA PINKY MEHUL SAHIL & ARMAAN Raffle 60 0 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH SURESH-PUSHPA, SNEHAL-RUPA & PARAG-TORAL BHANSALI Previous 49 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH KUSUM & DALPATLAL PARIKH FAMILY BY REKHA AND BIPIN PARIKH Previous 57 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH JAYANTILAL, NITIN-MEENA, MICHELLE, JESSICA, JAMIE SHAH Previous 54 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 0 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH IN PARENTS MEMORY BY PARESH,LOPA,JATIN AND AMIT SHAH FAMILY Gheeboli 59 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH SUSHILA-NAVIN SHAH AND FAMILY JAINIE JINESH PREM KOMAL KAJOL Raffle 60 0 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH DR.ANIL-BHARTI, RITESH & REEPAL SHAH Previous 36 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH ASHOK-DR. -

FT Pathshala Curriculum 2018-19.Xlsx

Stuti/Chaitya One time Grade Sutra Story Philosophy Activities Vandan/Stavan/Thoy Activity/Project Respect Teachers and Parents; Bhagwan and Chand Bow down to parents & elders; Pre-KG 1.Navkar Stuti- Prabhu Darshan Eight Kinds of Puja; 5 Khamasamna on kaushik, Past bhav of Bed time prayers (Shiyal Mara 3-4 3.Khamasamno 1st stanza 24 Tirthankar Names Gyan Pnchami Chand kaushik Santhare- Navkar tu maro bhai); Basic living non-living games How to hold Navkarvali; Goval Puts nails in Introduction to Jain Vocabulary Bhagvan's Ears; Due to like Jai Jinendra, Pranam, Pre-KG 2.Panchindiya Stuti- Prabhu Darshan Bhagvan's Karma During Bhagvan NavAngi 5 Khamasamna on Tirthankar, Puja, Aarti, Derasar, 4-5 4.Icchakar stanza 1 to 3 Tripristha Vasudev Bhav Puja Gyan Pnchami Upashray, Maharaj Saheb, (Putting Lead in Door Sadhviji etc.; Coloring and keeper's Ear) naming Lanchhans & Swapnas Stuti- Prabhu Darshan stanza 1 to 4; Shrimate Virnathay; Siddharath 5.Abhuthio Mahavir Swami Nirvan, Sut Vandie Tirthankar Names and KG 6.Iriya vahiyam Gautam Swami Keval To Dehrasar Activity Book (Chaityavandan), Din Lanchhans 7.Tassa uttari gyan, Bhaibij Dukhiyano Tu chhe beli (Stavan), Mahavir Jinanda (Thoy) Stuti- Prabhu Darshan stanza 1 to 6; Kamathe Dharnendra, Jai 8.Anathha Parshwanath Bhagvan and Activity Book and Alphabets A to 1 Chintamani Parshwanath Guruvandan Vidhi To Dehrasar 9.Loggas Kamath M (Chaitya vandan), Tu Prabhu Maro (Stavan), Pas Jinanda (Thoy) Stuti/Chaitya One time Grade Sutra Story Philosophy Activities Vandan/Stavan/Thoy Activity/Project -

The Heart of Jainism

;c\j -co THE RELIGIOUS QUEST OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, MA. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG MEN S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON AND H. D. GRISWOLD, MA., PH.D. SECRETARY OF THE COUNCIL OF THE AMERICAN PRESBYTERIAN MISSIONS IN INDIA si 7 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME ALREADY PUBLISHED INDIAN THEISM, FROM By NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., THE VEDIC TO THE D.Litt. Pp.xvi + 292. Price MUHAMMADAN 6s. net. PERIOD. IN PREPARATION THE RELIGIOUS LITERA By J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A. TURE OF INDIA. THE RELIGION OF THE By H. D. GRISWOLD, M.A., RIGVEDA. PH.D. THE VEDANTA By A. G. HOGG, M.A., Chris tian College, Madras. HINDU ETHICS By JOHN MCKENZIE, M.A., Wilson College, Bombay. BUDDHISM By K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. ISLAM IN INDIA By H. A. WALTER, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. JAN 9 1986 EDITORIAL PREFACE THE writers of this series of volumes on the variant forms of religious life in India are governed in their work by two impelling motives. I. They endeavour to work in the sincere and sympathetic spirit of science. They desire to understand the perplexingly involved developments of thought and life in India and dis passionately to estimate their value. They recognize the futility of any such attempt to understand and evaluate, unless it is grounded in a thorough historical study of the phenomena investigated. In recognizing this fact they do no more than share what is common ground among all modern students of religion of any repute. -

JCGB Rookies Curriculum.Xlsx

Jain Center of Greater Boston - Pathshala Curriculum Level : ROOKIE Jain Series Textbook - Standard 1 JCGB Prayer Book Jain Alphabet Book (JES 103) JES - 4 - Jain Lessons 1 Books Used: and 2 Topics -Year 1 September October November December January February March April May June Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra, Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra, Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra, Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra, Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra, Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra, Prayer/Sutra: Navkar Mantra Prayer/Sutra: Navkar Mantra Prayer/Sutra: Navakar Mantra Prayers/Sutras Chattari Mangalam Chattari Mangalam Chattari Mangalam Chattari Mangalam, Arahanto Chattari Mangalam, Arahanto Chattari Mangalam, Arahanto Final Exam on Prayers: Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Book: Jain Prarthanas Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Symbol of Thirthankaras: Rushabhdeva - Bullock Abhinandan Swami - Monkey Suparsvanatha - Swastik Shitalnatha - Four Petalled Emblem Vimalnatha - Boar Shantinath - Deer Mallinatha - Pitcher Neminatha - Conch Shell Revision of All Symbols Ajitnath - Elephant Sumatinatha - Crane Chandraprabha Swami - Moon Shreyansanatha - Rhinoceros Anantanatha - Hawk Kunthunath - Goat Munisuvrata Swami - Tortoise Parsvanatha - Snake Sambhavnatha - Horse Padmaprabha Swami - Lotus Suvidhinatha -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2017 Issue 12 CoJS Newsletter • March 2017 • Issue 12 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Muni Mahendra Kumar Ratnakumar Shah Professor J. Clifford Wright (University of Lyon) (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, India) (Pune) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Dr James Laidlaw Dr Kanubhai Sheth Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Cambridge) (LD Institute, Ahmedabad) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Dr Basile Leclère Dr Kalpana Sheth Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (University of Lyon) (Ahmedabad) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Dr Jeffery Long Dr Kamala Canda Sogani Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Elizabethtown College) (Apapramśa Sāhitya Academy, Jaipur) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg Dr Jayandra Soni Dr Sean Gaffney (Independent Scholar) (University of Tübingen) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Luitgard Soni Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Munich) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Professor Christoph Emmrich Gerd Mevissen Dr Herman Tieken Dr James Mallinson (University of Toronto) (Berliner Indologische Studien) (Institut Kern, Universiteit Leiden) South Asia Department Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari Professor Werner Menski (University of Würzburg) (Harvard Divinity School) (Banaras Hindu University) School of Law Dr Sherry Fohr Dr Andrew More Dr Himal Trikha Professor Francesca Orsini (Converse College) (University of Toronto) (Austrian Academy of Sciences) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Catherine Morice-Singh Dr Tomoyuki Uno Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris) (Chikushi Jogakuen University) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Professor Hampa P. -

Courses in Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2013 Issue 8 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Jaina Logic: Programme 7 Jaina Logic: Abstracts 10 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2012 12 SOAS Workshop 2014: Jaina Hagiography and Biography 13 Jaina Studies at the AAR 2012 16 The Intersections of Religion, Society, Polity, and Economy in Rajasthan 18 DANAM 2012 19 Debate, Argumentation and Theory of Knowledge in Classical India: The Import of Jainism 21 The Buddhist and Jaina Studies Conference in Lumbini, Nepal Research 24 A Rare Jaina-Image of Balarāma at Mt. Māṅgī-Tuṅgī 29 The Ackland Art Museum’s Image of Śāntinātha 31 Jaina Theories of Inference in the Light of Modern Logics 32 Religious Individualisation in Historical Perspective: Sociology of Jaina Biography 33 Daulatrām Plays Holī: Digambar Bhakti Songs of Springtime 36 Prekṣā Meditation: History and Methods Jaina Art 38 A Unique Seven-Faced Tīrthaṅkara Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum 40 Aspects of Kalpasūtra Paintings 42 A Digambar Icon of the Goddess Jvālāmālinī 44 Introducing Jain Art to Australian Audiences 47 Saṃgrahaṇī-Sūtra Illustrations 50 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund Publications 51 Johannes Klatt’s Jaina-Onomasticon: The Leverhulme Trust 52 The Pianarosa Jaina Library 54 Jaina Studies Series 56 International Journal of Jaina Studies 57 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 57 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 58 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 58 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 59 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover Gautama Svāmī, Śvetāmbara Jaina Mandir, Amṛtsar 2009 Photo: Ingrid Schoon 2 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christopher Key Chapple Dr Hawon Ku Professor J. -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 97 TO BE ANSWERED ON 25.4.2016 VAISAKHA 5, 1938 (SAKA) NATIONAL HERITAGE STATUS 97. SHRI B.V.NAIK; SHRI ARJUN LAL MEENA; SHRI P. KUMAR: Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has finalized its proposal for sending its entry for world heritage status long with the criteria to select entry for world heritage site status; (b) if so, the details thereof along with the names of temples, churches, mosques and monuments 2Iected and declared as national heritage in various States of the country, State-wise; (c) whether the Government has ignored Delhi as its official entry to UNESCO and if so, the details thereof and the reasons therefor; (d) whether, some sites selected for UNESCO entry are under repair and renovation; (e) if so, the details thereof and the funds sanctioned by the Government in this regard so far, ate-wise; and (f) the action plan of the Government to attract more tourists to these sites. ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE, CULTURE AND TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) AND MINISTER OF STATE, CIVIL AVIATION (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a) Yes madam. Government has finalized and submitted the proposal for “Historic City of Ahmedabad” as the entry in the cultural category of the World Heritage List for calendar year 2016-17. The proposal was submitted under cultural category under criteria II, V and VI (list of criteria in Annexure I) (b) For the proposal submitted related to Historic City of Ahmedabad submitted this year, list of nationally important monuments and those listed by Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation are given in Annexure II. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2008 Issue 3 CoJS Newsletter • March 2008 • Issue 3 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion and law; South Asian diaspora. ASSOCIATE MEMBERS Professor Lawrence A. Babb John Guy Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) History of medieval South India; Chola courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir Professor Phyllis Granoff (Sorbonne Nouvelle) (Yale University) Professor Ian Brown The modern economic and political Dr Piotr Balcerowicz Dr Julia Hegewald history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Warsaw) (University of Heidelberg) impact of the inter-war depression in South East Asia Nick Barnard Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain (Victoria and Albert Museum) (Muzaffarpur University) Dr Whitney Cox Sanskrit literature and literary theory, Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini Tamil literature, intellectual (University of Kolkata) (UC Berkeley) and cultural history of South India, History of Saivism Dr Rohit Barot Dr Whitney M. Kelting (University of Bristol) (Northeastern University Boston) Professor Rachel Dwyer Indian film; Indian popular culture; Professor Bhansidar Bhatt Dr Kornelius Krümpelmann Gujarati language and literature; Gujarati (University of Münster) (University of Münster) Vaishnavism; Gujarati diaspora; compara- tive Indian literature. -

Monumental Head of a Jina (P652)

Monumental head of a Jina (P652) What do we like in this sculpture? - A very rare colossal head belonging to one of the three most revered Jina (or Tīrthaṅkara) of the Jain tradition. - Idealized facial features and harmonious curves reminiscent of the great classical aesthetics of the Gupta Empire. - A finesse of sandstone with warm colors reflected in a variety of red and brown tones. I. Detailed description Monumental head of a Jina (P652) Sandstone India Circa 9th-10th century H. 35 cm or 13 ¾ in Jainism, an Indian religion predating Buddhism Jain sanctuaries have countless depictions of the Tirthaṅkara, also called Jina, omniscient beings who have broken free from the cycle of reincarnation. These extraordinary characters, twenty-four in number, of which there are twenty-four, existed down through the ages and are responsible for transmitting the foundations of Jain doctrine through the centuries. This doctrine predates Buddhism and one of its fundamental principles is non-violence (ahiṃsā), which applies to all creatures. This superb head could represent Mahāvīra (the "great hero") because its halo is a blooming lotus flower that was originally part of the throne upon which the deity seated. The figure shows a skillful blend of expressive vigor and delicacy. The Jina's moral virtue The "Conqueror" or “Victor” (jina) was surely figured naked, as tradition dictates, sitting in the lotus position, hands in the lap, with a halo and protected by two parasols on top of each other. At the age of thirty, the prince Vardhamāna became a sādhanā (ascetic), gave up after a few months all clothing judging that detachment from the world required the nudity, practiced by the community Digambarā and some Sādhu, he devoted himself for twelve and a half years to meditation and long periods of fasting.