Research Exhibitions Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

02. Megalo Print Studio and Gallery

Ms Amanda Bresnan MLA Chair Standing Committee on Education, Training and Youth Affairs ACT Legislative Assembly Inquiry into the future use of the Fitters Workshop in the Kingston Arts Precinct Dear Ms Bresnan Please find attached Megalo Print Studio + Gallery’s submission to the Inquiry. This submission supports the decision to relocate Megalo to the Fitters Workshop in the Kingston Visual Arts Precinct. Megalo Print Studio + Gallery looks forward to the opportunity to appear before the Standing Committee to provide further information and clarification of the issues outlined in our submission. Should the Committee require any further information or assistance during its Inquiry, please contact Artistic Director/CEO, Alison Alder (Tel: 6241 4844 / email [email protected]. Yours sincerely Erica Seccombe Chair, Megalo Board. Megalo Print Studio + Gallery Submission to the Standing Committee on Education Training and Youth Affairs “Inquiry into the future use of the Fitters Workshop in the Kingston Arts Precinct” Renowned Australian Artist Mike Parr, with Master Printmaker John Loane, giving a demonstration in conjunction with the National Gallery of Australia public programs, Megalo 2011 Prepared by Megalo Print Studio + Gallery Contact Alison Alder, Artistic Director 49 Phillip Avenue, Watson ACT 2602 T: 6241 4844 [email protected] www.megalo.org 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................... page 4 2. The unique role of printmaking in Australia’s cultural history .............. page 5 3. Community demand for a print studio in the region .......................... page 5 3.1 Participation in the visual arts .................................. page 5 3.2 Attendance at art galleries ....................................... page 6 3.3 Economic contribution to the visual arts .................... -

27 May 2020 Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda

Ordinary Council Meeting 27 May 2020 Council Chambers, Town Hall, Sturt Street, Ballarat AGENDA Public Copy Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda 27 May 2020 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT A MEETING OF BALLARAT CITY COUNCIL WILL BE HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, TOWN HALL, STURT STREET, BALLARAT ON WEDNESDAY 27 MAY 2020 AT 7:00PM. This meeting is being broadcast live on the internet and the recording of this meeting will be published on council’s website www.ballarat.vic.gov.au after the meeting. Information about the broadcasting and publishing recordings of council meetings is available in council’s broadcasting and publishing recordings of council meetings procedure available on the council’s website. AGENDA ORDER OF BUSINESS: 1. Opening Declaration........................................................................................................4 2. Apologies For Absence...................................................................................................4 3. Disclosure Of Interest .....................................................................................................4 4. Confirmation Of Minutes.................................................................................................4 5. Matters Arising From The Minutes.................................................................................4 6. Public Question Time......................................................................................................5 7. Reports From Committees/Councillors.........................................................................6 -

Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative : a Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative: A Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand Soldier David Guerin 94114985 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Cover) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). (Above) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 2/1498, New Zealand Field Artillery, First New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 1915, left, & 1917, right. 2 Dedication Dedicated to: Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 1893 ̶ 1962, 2/1498, NZFA, 1NZEF; Alexander John McKay Manson, 11/1642, MC, MiD, 1895 ̶ 1975; John Guerin, 1889 ̶ 1918, 57069, Canterbury Regiment; and Christopher Michael Guerin, 1957 ̶ 2006; And all they stood for. Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). 3 Acknowledgements Distinguished Professor Sally J. Morgan and Professor Kingsley Baird, thesis supervisors, for their perseverance and perspicacity, their vigilance and, most of all, their patience. With gratitude and untold thanks. All my fellow PhD candidates and staff at Whiti o Rehua/School of Arts, and Toi Rauwhārangi/ College of Creative Arts, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa o Pukeahu Whanganui-a- Tara/Massey University, Wellington, especially Jess Richards. -

The Meaning of Folklore: the Analytical Essays of Alan Dundes

Play and Folklore no. 52, November 2009 Play and Folklore Music for Children in the Torres Strait - the Recordings of Karl Neuenfeldt Kids can Squawl: Politics and Poetics of Woody Guthrie’s Children Songs Tradition, Change and Globalisation in Moroccan Children’s Toy and Play Culture The Meaning of Folklore: The Analytical Essays of Alan Dundes Sydney High School Playground Games and Pranks A Cross-cultural Study: Gender Differences in Children’s Play 1 From the Editors Play and Folklore no. 52 has been an unusual challenge, with articles from Beijing, Rome and France dealing with aspects of children’s play in China, the Netherlands, America and Morocco. The issue also includes articles from Perth and Sydney, and the historical perspective runs from the 12th century to the present day. As the year 2009 is ending, the project ‘Childhood, Tradition and Change’ is entering its fourth, and final, year. This national study of the historical and contemporary practices and signifi- cance of Australian children’s playlore has been funded by the Australian Research Council together with Melbourne, Deakin and Curtin Universities and the National Library of Australia and Museum Victoria. In 2010 the research team will be carrying out its final fieldwork in primary school playgrounds, beginning the analysis of the rich body of data already obtained, and preparing the book which is the project’s final outcome. We are pleased to include Graham Seal’s review of the analytic essays of Alan Dundes, as edited by Simon Bronner. Both the book itself and Seal’s review pay tribute to the seminal work of one of the world’s most distinguished folklorists. -

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

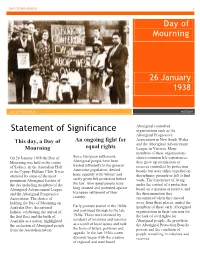

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Patrick Stevedores Port Botany Container Terminal Project Section 75W Modification Application December 2012

Patrick Stevedores Operations No. 2 Patrick Stevedores Port Botany Container Terminal Project Section 75W Modification Application December 2012 Table of contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The proponent ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 The site ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Project context ................................................................................................................ 4 1.5 Document structure ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Project description ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Key aspects of the project ............................................................................................... 6 2.2 Demolition, enabling and construction works ................................................................. 10 2.3 Operation ...................................................................................................................... 12 2.4 Construction workforce and working hours.................................................................... -

Australia's National Heritage

AUSTRALIA’S australia’s national heritage © Commonwealth of Australia, 2010 Published by the Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts ISBN: 978-1-921733-02-4 Information in this document may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, provided that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Heritage Division Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Email [email protected] Phone 1800 803 772 Images used throughout are © Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and associated photographers unless otherwise noted. Front cover images courtesy: Botanic Gardens Trust, Joe Shemesh, Brickendon Estate, Stuart Cohen, iStockphoto Back cover: AGAD, GBRMPA, iStockphoto “Our heritage provides an enduring golden thread that binds our diverse past with our life today and the stories of tomorrow.” Anonymous Willandra Lakes Region II AUSTRALIA’S NATIONAL HERITAGE A message from the Minister Welcome to the second edition of Australia’s National Heritage celebrating the 87 special places on Australia’s National Heritage List. Australia’s heritage places are a source of great national pride. Each and every site tells a unique Australian story. These places and stories have laid the foundations of our shared national identity upon which our communities are built. The treasured places and their stories featured throughout this book represent Australia’s remarkably diverse natural environment. Places such as the Glass House Mountains and the picturesque Australian Alps. Other places celebrate Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture—the world’s oldest continuous culture on earth—through places such as the Brewarrina Fish Traps and Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry. -

Tjayiwara Unmuru Celebrate Native Title Determination

Aboriginal Way Issue 54, October 2013 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Tjayiwara Unmuru celebrate native title determination Tjayiwara Unmuru Federal Court Hearing participants in SA’s far north. De Rose Hill achieves Australia’s first native title compensation determination Australia’s first native title The name of De Rose Hill will go down Under the Native Title Act, native title and this meant open communication compensation consent in Australian legal history for a number holders may be entitled to compensation between parties and of course determination was granted to of reasons. on just terms where an invalid act impacts overcoming the language barriers and on native title rights and interests. we thank the State for its cooperation the De Rose Hill native title “First, because you brought one of the for what was at times a challenging holders in South Australia’s early claims for recognition of your native Karina Lester, De Rose Hill Ilpalka process,” said Ms Lester. far north earlier this month. title rights over this country, and because Aboriginal Corporation chairperson you had the first hearing of such a claim said this is also a significant achievement Native title holder Peter De Rose said the The hearing of the Federal Court was in South Australia.” for the State, who played a key role in compensation determination was a better held at an important rock hole, Ilpalka, this outcome and have worked closely experience compared to the group’s fight on De Rose Hill Station. Now, again, you are leading the charge. with De Rose Hill Ilpalka Aboriginal for native title recognition which lasted This is the first time an award of Corporation through the entire process. -

Australian Hall

150-2 ELIZABETH ST, SYDNEY 1 Australian Hall 150-2 Elizabeth St Sydney 150-2 ELIZABETH ST, SYDNEY HISTORY Knights of the Southern Cross, a Statement of Significance Catholic fraternal lay group linked with the Catholic Right and, The Australian Hall holds social William Ferguson ultimately with the split in the significance for at least three Tom Foster Labor Party in the 1950s. groups of people. Pearl Gibbs The building was initially built to Helen Grosvenor Firstly, the building holds social be used as a meeting place for Jack Johnson significance for the Aboriginal cultural and social activities and People for its role in the 1938 Jack Kinchela was continuously used for these "Day of Mourning" meeting. Bert Marr events including cinema and Pastor Doug Nicholls theatre. It is a rare example of a This event was the first protest by Henry Noble purpose built building in Sydney Aboriginal people for equal Jack Patten continuously used for its initial opportunities within Australian Tom Pecham purpose. Society. It was attended by Frank Roberts approximately 100 people of Margaret Tucker The building holds architectural Aboriginal Blood and was the significance as it still contains beginning of the contemporary Secondly, it holds significance for some examples of original Aboriginal Political Movement. the German and Greek-Cypriot architecture. It is a good example Among those who contributed communities in Sydney as it of the Federation Romanesque significantly to the movement allowed visitors and migrants to style. The interior also contains generally and particularly to the enjoy cultural and social events. examples of certain features that event in the Australian Hall were: The building also has an could date from the original Mrs Ardler association with Australian construction and also has features J Connelly national and political history in its from each of the renovations William Cooper ownership (1920-79) by the since. -

March 2016 Council Meeting Minutes

MINUTES OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF THE TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL HELD IN THE SHIRE OFFICES, DOUGLAS STREET, THURSDAY ISLAND ON TUESDAY, 15 MARCH 2016 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PRESENT Mayor Pedro Stephen AM (Chair), Cr. Yen Loban, Cr. John Abednego, Cr. Allan Ketchell, Dalassa Yorkston (Chief Executive Officer), Andrew Brown (Director Corporate and Community Services), Bill Cuthbertson (Director Engineering and Infrastructure Services) and Nola Ward Page (Minute Secretary) The meeting opened with a prayer by Mayor Stephen at 9.08am. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Mayor acknowledged the traditional owners The Kaurareg People upon whose land we hold our meeting also the elders representing the clans from the four winds of Zenadth Kes. APOLOGY An apology was received from Cr. Willie Wigness. Min. 16/03/1 Moved Cr. Loban, Seconded Cr. Abednego “That the apology received from Cr. Wigness be accepted.” Carried CONDOLENCES As a mark of respect, Council observed a minute’s silence in memory of: Elder Palm Baigau Stephen Mr Ali Drummond (Snr) Ms Sarah (Serai) Lowah Mr Leigh Milbourne Ms Melora Elthia Nai Arthur Pitt Pauls Mills DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST UNDER THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT - Nil CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Min. 16/03/2 Moved Cr. Ketchell, Seconded Cr. Loban “That Council receive the Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of 16 February 2016 and confirm as a true and correct record of the proceedings.” Carried MATTERS OF ACTION FROM PREVIOUS MEETING - Nil MAYOR’S REPORT Acknowledgement of the Zendath Kes Traditional Owners past and present Queensland Road Safety Grant The Department of Transport and Main Roads offers funding to community groups for community initiatives that work to address road safety issues in support of the strategic objectives of the Queensland Road Safety Action Plan 2015-2017 and the Queensland Road Safety Strategy 2015-2012. -

Publisher Version (Open Access)

Issue No. 7 (September 2003) — New Media Technologies The Technology, Aesthetic and Cultural Politics of a Collaborative, Transnational Music Recording Project: Veiga, Veiga and the Itinerant Overdubs By Denis Crowdy and Karl Neuenfeldt New media innovations and the popularity of ‘world music’ have facilitated crosscultural and transnational recording projects in the past few decades. New media technology makes collaboration at a distance feasible and a market for the very eclectic genre(s) of ‘world music’ makes projects potentially economically viable. Beginning approximately in the mid- 1980s with the popularity, and contentiousness, of Paul Simon’s Graceland project (Meintjes 1990) and other ‘world music’ projects such as Deep Forest (Feld 2000), academic researchers have explored the nature, legality and cultural dynamics of such recordings (e.g. Mills 1996; Zemp 1996). An ancillary to such research has been research into the multifaceted roles of academics in such kinds of cultural production. Cultural production here includes the overlapping components of most contemporary cultural products, including their ‘circuit of culture’ (production, regulation, identity, representation and consumption) (Du Gay 1997). Such research provides insights into the processes and end products of cultural production of a particular ‘art world’ of shared aesthetics (Becker 1982), in this case popular music. Examples of such academic involvement include: production and participation in educational dance performances (Mackinlay 2001), soundscape and acoustic ecology recordings (Feld 1991, 2001; Feld and Crowdy 2002), and commercial or community-orientated music CDs (Scales 2002, Neuenfeldt 2001). This article describes and analyses the aesthetic, technological and cultural processes informing the cultural production of Veiga, Veiga, a song recorded by 73-year-old Australian Torres Strait Islander Henry (Seaman) Dan. -

AIATSIS Guidelines for Ethical Publishing 5

Guidelines for the ethical publishing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors and research from those communities Aboriginal Studies Press The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies First published in 2015 by Aboriginal Studies Press © The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its education purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Aboriginal Studies Press is the publishing arm of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. GPO Box 553, Canberra, ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1183 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4288 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/asp/about.html Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this publication contains names and images of people who have passed away. Guidelines for ethical publishing 3 Welcome (from the AIATSIS Principal) I’m pleased to have the opportunity to welcome readers to these guidelines for ethical publishing. As the Principal of AIATSIS, of which Aboriginal Studies Press (ASP) is the publishing arm, I’ve long had oversight of ASP’s publishing and I’m pleased to see these guidelines because they reflect ASP’s lived experience in an area in which there have been no clear rules of engagement but many criticisms of the past practices of some researchers, writers, editors and publishers.