Restoring a Free-Flowing Huron River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Huron River History Book

THE HURON RIVER Robert Wittersheim Over 15,000 years ago, the Huron River was born as a small stream draining the late Pleistocene landscape. Its original destination was Lake Maumee at present day Ypsilanti where a large delta was formed. As centuries passed, ceding lake levels allowed the Huron to meander over new land eventually settling into its present valley. Its 125 mile journey today begins at Big Lake near Pontiac and ends in Lake Erie. The Huron’s watershed, which includes 367 miles of tributaries, drains over 900 square miles of land. The total drop in elevation from source to mouth is nearly 300 feet. The Huron’s upper third is clear and fast, even supporting a modest trout fishery. The middle third passes through and around many lakes in Livingston and Washtenaw Counties. Eight dams impede much of the Huron’s lower third as it flows through populous areas it helped create. Over 47 miles of this river winds through publicly owned lands, a legacy from visionaries long since passed. White Lake White Lake Mary Johnson The Great Lakes which surround Michigan and the thousands of smaller lakes, hundreds of rivers, streams and ponds were formed as the glacier ice that covered the land nearly 14,000 years ago was melting. The waters filled the depressions in the earth. The glaciers deposited rock, gravel and soil that had been gathered in their movement. This activity sculpted the land creating our landscape. In section 28 of Springfield Township, Oakland County, a body of water names Big Lake by the area pioneers is the source of the Huron River. -

Huron River Water Trail Trip Description 1 Hudson Mills Metropark

Huron River Water Trail Trip Description Hudson Mills Metropark (Mile 67) to Delhi Metropark (Mile 58.3) - 3.5 hours; 8.7 miles Launch at the Rapids View Picnic Area in Hudson Mills Metropark, near North Territorial Road. This trip provides easy access to both launch and take-out sites. Paddle through parkland and then into Dexter. TRIP DESCRIPTION: Excerpt from “Canoeing Michigan Rivers: A Comprehensive Guide to 45 Rivers” by Jerry Dennis and Craig Date provided with permission from Thunder Bay Press. Put in at Hudson Mills Metropark, where there is good access and parking just below Territorial Road [at the Rapids View Picnic Area]. Upstream, fair access and parking are found a Bell Road. [Note: Launching at Bell Road will take you past the Hudson Mills canoe campground and rapids where a portage is recommended.] The river here is 60-90 feet wide and alternates sections of slow water one to four feet deep with sections of very shallow riffles. Low water in summer will produce some bottom-bumping. Hudson Mills has been the site of a saw mill, grist mill, cider mill and plaster mill, the earliest dating back to 1827. Today, only the ruins of foundations and a short stretch of light rapids mark the spot just below Territorial Road Bridge where the mills were located. The rapids can be run down the chute at left center. Pumpkin- to bushel-size rocks create standing waves that could become fairly high during high water. If in doubt, portage on the left just beyond the bridge. Light riffles extend well into Hudson Mills Metropark, where there are several access sites and two overnight canoe campgrounds. -

Delhi Metropark

PARK MAP Park Entrance H udso GPS: 42º23’18.52”N 83º54’12.17”W n Mills M etropa te rk i s S s West HUR e c c River ON RIVER DR Trail to g A n Dexter i CHAMBERLIN RD h s Fi Hur HUR o r n R e Group iv D ON RIVER DR e r elh Camp i n Riv Me o tr r op u ar H Labyrinth k 1 3 2 NOR PARK ENTRANCE TH TERRIT GPS: 42º23’11.88”N 83º54’31.13”W ORIAL RD DEXTER-HURON METROPARK 6535 Huron River Drive, Dexter, MI 48130 (Administered through Hudson Mills Metropark) Rapids View 734-426-8211 • www.metroparks.com Service 23 Area MAP KEY PICNIC SHELTERS Outdoor Sports Small Boat Launch 1 West HUR Restroom Toll Booth 2 Central River Grove ON RIVER DR Oak ROADS AND TRAILS 3 East 2 Meadows Paved Road Paved Hike-Bike Trail Dirt Road Railroad Track Nature Trail FEET 0 250 500 750 1000 MILES 0 ¼ lls Met Y RD Y Mi ropa son rks ud H & on ur H r- W HUR te Activity Center ex E TER PINCKN TER D ON RIVER DR Hur X DE on Riv r 4 ive West er ron R Delhi HUR u H DELHI CT ON RIVER DR DELHI METROPARK 1 3902 East Delhi Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 HUDSON MILLS (Administered through E DELHI RD Hudson Mills Metropark) East METROPARK 5 734-426-8211 Park Entrance Delhi 8801 North Territorial Road www.metroparks.com GPS: 42º19’55.99”N 83º48’37.65”W Pineview A Dexter, MI 48130 n GREGORY RD MAP KEY n 734-426-8211 A r www.metroparks.com Restrooms b RAILR o H OAD ST r u Small Boat Launch ro MAP KEY n R iv Camping er Boat Rental D Toll Booth Disc Golf e x t e r - Playground Outdoor Sports H u r o n Outdoor Sports & D e Paved Road Playground lh i FLEMMING RD M e Dirt Road Golf t r o p a r Railroad Track Restroom k s Small Boat Launch PICNIC SHELTERS FEET 0 250 500 750 1000 1 North Shelter Toll Booth MILES 0 ¼ Trail-head Waterslide WHITMORE Paved Roads LAKE 23 Dirt Roads N. -

History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966 - 2003

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966 - 2003 Mike Thomas, Research Biologist (retired) and Todd Wills, Area Station Manager Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Lake St. Clair Great Lakes Station was constructed on a confined dredge disposal site at the mouth of the Clinton River and opened for business in 1974. In this photo, the Great Lakes Station (red roof) is visible in the background behind the lighter colored Macomb County Sheriff Marine Division Office. Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station Website: http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-153-10364_52259_10951_11304---,00.html FISHERIES DIVISION LSCFRS History - 1 History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966-2003 Preface: the other “old” guys at the station. It is my From 1992 to 2016, it was my privilege to hope that this “report” will be updated serve as a fisheries research biologist at the periodically by Station crew members who Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station have an interest in making sure that the (LSCFRS). During my time at the station, I past isn’t forgotten. – Mike Thomas learned that there was a rich history of fisheries research and assessment work The Beginning - 1966-1971: that was largely undocumented by the By 1960, Great Lakes fish populations and standard reports or scientific journal the fisheries they supported had been publications. This history, often referred to decimated by degraded habitat, invasive as “institutional memory”, existed mainly in species, and commercial overfishing. The the memories of station employees, in invasive alewife was overabundant and vessel logs, in old 35mm slides and prints, massive die-offs ruined Michigan beaches. -

Detroit River Group in the Michigan Basin

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 133 September 1951 DETROIT RIVER GROUP IN THE MICHIGAN BASIN By Kenneth K. Landes UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Washington, D. C. Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Introduction............................ ^ Amherstburg formation................. 7 Nomenclature of the Detroit River Structural geology...................... 14 group................................ i Geologic history ....................... ^4 Detroit River group..................... 3 Economic geology...................... 19 Lucas formation....................... 3 Reference cited........................ 21 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Location of wells and cross sections used in the study .......................... ii 2. Correlation chart . ..................................... 2 3. Cross sections A-«kf to 3-G1 inclusive . ......................;.............. 4 4. Facies map of basal part of Dundee formation. ................................. 5 5. Aggregate thickness of salt beds in the Lucas formation. ........................ 8 6. Thickness map of Lucas formation. ........................................... 10 7. Thickness map of Amherstburg formation (including Sylvania sandstone member. 11 8. Lime stone/dolomite facies map of Amherstburg formation ...................... 13 9. Thickness of Sylvania sandstone member of Amherstburg formation.............. 15 10. Boundary of the Bois Blanc formation in southwestern Michigan. -

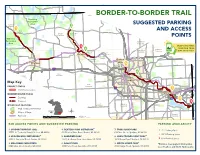

Suggested Parking and Access Points

Stockbridge Unadilla Putnam Township Township Township Border-to-Border Trail: 36 36 Overview and Phasing Stockbridge Unadilla Putnam STtoocwknbsrhidipge TUonwandsihllaip TPoPuwtinnnsahcmipkney D Township Township Township e Border-to-Border Trail: xt "The Huron River Greenway" Stockbridge n e o r t Border-to-Border Trail: m P s a Ypsilanti - Ann Arbor - Dexter - Lakelands Trail i 36 e Overview and Phasing n g h ke k 36 n La ckn a n o g t rs L Hamburg i Pa t e 36 y Overview and Phasing n v e r I r i 36 e "The Huron Waterloo Loop" Stockbridge Unadilla PPutinnacmkney y wb Township n L a Livingsto Str Township Township ToPwinnshcipkneD y Dexter - Chelsea - Stockbridge - Lakelands Trail Ingham e xt enaw "The Huron River Greenway" Stockbridge SUntaodillca kbridge n Putnam Washt D Border-to-Border Trail: e o Webster e r t Township m Township Township Jackson September 2019 - Prepared By: Washtenaw County Parks xt "The Huron River Greenway" P Stockbridge n s a Township Ypsilanti - Ann Arbor - Dexter - Lakelands Trail e i e o n g h k r t e m k a ckn n L 36 a Overview and Phasing P n o g L s s Hamburg a t r i 36 a t e Ypsilanti - Ann Arbor - Dexter - Lakelands Trail P i y e n n g v h k e r I ke ckn r i La e a "The Huron Waterloo Loop" 36 n y n o g t rs b L THoawmnbsuhrigp i a t e w n L ingsto 36 Pinckney P tra y Liv n v e S r I Pinckney r i e Dex"teTrh - eCh Helsuerao - nSt oWckabrtiedgrel o- oLa kLeolaondps "Trail y wb Township n L ingsto Ingham D a Liv Pinckney Recreation Str Washtenaw e Dexter - Chelsea - Stockbridge - Lakelands Trail D xt -

Lake Erie Metropark

PARK MAP LAKE ERIE 7 mile Hike-Bike Trail Connector METROPARK to Oakwoods 32481 West Jeerson Avenue S GIBRALTAR RD Brownstown, MI 48173 734-379-5020 Bro wn sto reek GOLF COURSE wn C 14786 Lee Road Battle of Brownstown Detroit River Brownstown, MI 48173 Monument 734-379-0048 MARINA WOODRUFF RD Wyman’s Canal 35001 Milleville Road Overlook Brownstown, MI 48173 BOAT, CANOE AND MAP KEY Eagle’s Way Overlook KAYAK LAUNCH Rental Shelter Hawthorn Outer Buoys Sanger’s Lagoon GPS: 42º04’43”N 83º11’27”W Thicket Overlook Restrooms Riley Creek Overlook Boat Softball Diamond House and Dock MARSHLANDS MUSEUM Basketball Court Tennis Court Volleyball Court PARK OFFICE Playground 734-379-5020 W JEFFERSON AVE JEFFERSON W Paved Hike-Bike Trail Lotus Beds PICNIC SHELTERS Toll A American Lotus Park Entrance A GPS: 42º04’14”N 83º12’36”W B Blue Heron Service C Cattail Area Sturgeon Bar B Island D Wood Duck GREAT WAVE AREA Wave Pool, Playground, E Muskrat HURON RIVER DR First Aid, Food Bar, and Sledding Hill C NATURE TRAILS Big Turtle Shortcut - ½ mile PLEASANT DR MCCANN RD Trapper’s Run - 1 mile Shore Fishing Cherry Island Trail - 1¼ miles Boardwalk D STREICHER RD E N COVE POINT PICNIC AREA Driving Range GOLF COURSE 734-379-0048 MARINA OFFICE Marina Point Observation GPS: 42º03’13.06”N 83º12’0.12”W Deck and Fishing Site W JEFFERSON AVE JEFFERSON W 734-379-5020 GPS: 42º03’12.67”N 83º11’33.04”W Service Area LEE RD MARINA Outer Buoys HEIDE RD Ice Fishing GPS: 42º03’12”N 83º11’02”W SOVEY MARLEY AVE ERIE DR MILLEVILLE RD MILLEVILLE Lake Erie H CAMPAU RD A R B I N -

Huron River Report – Fall 2017

Huron River Report Published quarterly by the Huron River Watershed Council FALL 2017 feature story Fishing the Home Waters Huron River becomes a destination for anglers The naturally nutrient-rich waters establishment of bait and guide shops of the Huron River and some of its in the watershed (see list, page 5). tributaries offer great habitat for a Here is the angler’s report. wide variety of fish. The prize fish found in these home waters attract The upper Huron anglers from diverse backgrounds, The upper headwaters of the Huron using an array of fishing styles. contain lakes with a variety of sizes Annually, the Huron River attracts and depths, producing a diversity 250,000 visitor-days for fishing, of fish populations. Larger lakes according to a study by Grand Valley like Kent and Pontiac have public State University (see article, page 10). access points that anglers can use So what are all these anglers looking to test the fishing waters. Many of for and how are they doing it? The the smaller lakes are private and answer depends on who you ask and accessible only by those owning where you are on the river system. lakefront property. Typically, anglers HRWC staff talk with many excited in the headwaters region approach anglers about their observations, by boat, floating or anchoring off These big smallmouth beauties can be successes, failures, and ideas shoals, underwater ridges or natural found at many locations along the river. about improving the game fishery. credit: Schultz Outfitters This interest encourages the continued on page 4 Planning Ahead Local governments and residents are key to the health of the Huron The Huron River is currently the supplies the Huron with clear, cool, spaces to the watershed’s health, it is cleanest river in Southeast Michigan. -

Edison Power Plant Historic District

Final Report of the Historic District Study Committee for the City of Ypsilanti, Washtenaw County, Michigan This Report has been prepared by the Historic District Study Committee appointed by the City Council, City of Ypsilanti, Michigan, on July 15, 2008, to study and report on the feasibility of providing legal protection to the Edison Power Plant, Dam, and Peninsular Paper Company Sign by creating the three-resource Edison Power Plant Historic District Submitted to Ypsilanti City Council December 15, 2009 Contents Charge of the Study Committee .............................................................................. 1 Composition of the Study Committee ..................................................................... 1 Verbal boundary description (legal property description) .................................. 2 Visual boundary description (maps) ...................................................................... 2 Washtenaw County GIS aerial view of Peninsular Park, location of Edison Power Plant, showing power plant, dam, parking area, park pavilion, & dock City of Ypsilanti zoning map showing Peninsular Park City of Ypsilanti Image/Sketch for Parcel: 11-11-05-100-013 Sanborn Insurance map, 1916 Sanborn Insurance map, 1927 Proposed Boundary Description, Justification, & Context Photos ...................... 8 Criteria for Evaluating Resources .......................................................................... 11 Michigan’s Local Historic Districts Act, 1970 PA 169 U.S. Secretary of the Interior National Register -

Millers Creek Watershed Manangment Plan Part 2

5. EXISTING CONDITIONS This section is a general overview of conditions of Millers Creek and its watershed. Descriptions of individual reaches (sections of the stream) are also summarized in this chapter. Detailed descriptions of individual reaches within the creek, along with detailed site maps and photographs can be found in Appendix D. All the mapping data, in ArcMap format, can be found in Appendix E. A map of the reaches is shown in Figure 5.1. Each reach is referred to by the sampling station name at the downstream end of that reach. For example, the Plymouth reach ends at the Plymouth sampling station and includes all channel upstream of this sampling station. The Baxter reach begins at the Plymouth sampling station and ends at the Baxter sampling station. In some areas, the reaches are broken up into sub-reaches due to the heterogeneity of conditions within that reach. 5.1 General conditions Climate In Ann Arbor on average, 32-35 inches of total annual precipitation falls during roughly 120 days of the year (UM weather station data, See Appendix F). Over half the days with precipitation, the total precipitation amounts to 0.1 inches or less. On any given year, 90% of all daily precipitation events result in a 24-hour total depth of 0.66 inches or less. It is also highly probable in any given year that there are only 3 or 5 events with a 24-hour total of an inch or more of precipitation. During January, typically the coldest month of the year, temperatures average between 16 and 30 degrees Fahrenheit (°F). -

Peninsular Paper Dam: Dam Removal Assessment and Feasibility Report Huron River, Washtenaw County, Michigan

Silver Brook Watershed Riparian Buffer Restoration Report Great Swamp Watershed Association July 2018 PENINSULAR PAPER DAM: DAM REMOVAL ASSESSMENT AND FEASIBILITY REPORT HURON RIVER, WASHTENAW COUNTY, MICHIGAN SEPTEMBER 2018 PREPARED FOR: PREPARED BY: HURON RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL PRINCETON HYDRO 1100 NORTH MAIN, SUITE 210 931 MAIN STREET, SUITE 2 ANN ARBOR, MI 48104 SOUTH GLASTONBURY, CT 06073 734-769-5123 860-652-8911 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Three Critical Issues ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Firm Overview .......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Site Description .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Review of Existing Files and Historical Documents ......................................................................................................... 3 Field Investigation, Survey, and Observations ................................................................................................................ 4 Vibracoring and Sediment Sampling ................................................................................................................................ -

Huron River and Impoundment Management Plan

Huron River and Impoundment Management Plan Our vision for the future of the Huron River in Ann Arbor can be summarized as: A healthy Huron River ecosystem that provides a diverse set of ecosystem services. We envision a swimmable, fishable and boatable river, including both free-flowing and impounded segments, which is celebrated as Ann Arbor’s most important natural feature and contributes to the vibrancy of life in the city. The river and its publicly-owned shoreline and riparian areas create a blue and green corridor across the city that contains restored natural areas and adequate, well-sited public trails and access. Ample drinking water, effective wastewater removal and a full range of high quality passive and active recreation and education opportunities are provided to the citizens of Ann Arbor. Ongoing public engagement in the river’s management leads to greater stewardship and reduced conflict among users. Our approach to management creates a model that other communities upstream and downstream emulate. Executive Summary The Huron River and Impoundment Management Plan Committee is pleased to provide the following draft plan, report, and recommendations to the Environmental Commission and City Council for their review and approval. The committee has met for the past two years to better understand the sometimes-complex interrelationships among the Huron river ecology, community recreation preferences, the effect of dams on river processes, and the economic implications of different recommendations. The Committee heard presentations from key user groups (e.g., anglers, paddlers and rowers, among others) and regulatory agencies (e.g., MDEQ Dam Safety, MDNR Fisheries). The committee included representatives from key user groups and community organizations including river residents, rowers, paddlers, anglers, the University of Michigan, Detroit Edison, the Environmental Commission, Park Advisory Commission, Planning Commission, and the Huron River Watershed Council.