From the SADF to the SANDF: Safegaurding South Africa for a Better Life for All?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Storm Over Malema's Tender Excesses

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Thursday 23 September 2021 Media storm over Malema's tender excesses A picture of unrestrained excess and cronyism is painted in three Sunday newspaper reports claiming ANC Youth League president Julius Malema's millionaire lifestyle is being bank-rolled by lucrative government contracts awarded to his companies, writes Legalbrief. The Sunday Times, City Press and Rapport all allege Malema has benefited substantially from several tenders - and that most of them stem from his home province Limpopo, where he wields significant influence. According to the Sunday Times, official tender and government documents show Malema was involved in more than 20 contracts, each worth between R500 000 and R39m between 2007 and 2008. One of Malema's businesses, SGL Engineering Projects, has profited from more than R130m worth of tenders in just two years. Among the tenders awarded to SGL, notes the report, was one by Roads Agency Limpopo, which has a budget of over R2bn, and which is headed by Sello Rasethaba, a close friend of Malema. Rasethaba was appointed last year shortly after Malema's ally, Limpopo Premier Cassel Mathale, took office. Full Sunday Times report Full City Press report Full report in Rapport Both the ANC and the Youth League have strongly defended Malema, In a report on the News24 site, the ANC pointed out Malema had not breached any law or code of ethics by being involved in business. Spokesperson Brian Sokutu said: 'Comrade Malema is neither a member of Parliament or a Cabinet Minister and he has therefore not breached any law or code of ethics by being involved in business.' ID leader Patricia De Lille said Malema should stop pretending to represent the poor when he was living in opulence earned from the poor and ordinary taxpayers in a society plagued by the worst inequalities in the world. -

Dodannualreport20042005.Pdf

chapter 7 All enquiries with respect to this report can be forwarded to Brigadier General A. Fakir at telephone number +27-12 355 5800 or Fax +27-12 355 5021 Col R.C. Brand at telephone number +27-12 355 5967 or Fax +27-12 355 5613 email: [email protected] All enquiries with respect to the Annual Financial Statements can be forwarded to Mr H.J. Fourie at telephone number +27-12 392 2735 or Fax +27-12 392 2748 ISBN 0-621-36083-X RP 159/2005 Printed by 1 MILITARY PRINTING REGIMENT, PRETORIA DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2004 - 2005 chapter 7 D E P A R T M E N T O F D E F E N C E A N N U A L R E P O R T 2 0 0 4 / 2 0 0 5 Mr M.G.P. Lekota Minister of Defence Report of the Department of Defence: 1 April 2004 to 31 March 2005. I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Defence. J.B. MASILELA SECRETARY FOR DEFENCE: DIRECTOR GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2004 - 2005 i contents T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S PAGE List of Tables vi List of Figures viii Foreword by the Minister of Defence ix Foreword by the Deputy Minister of Defence xi Strategic overview by the Secretary for Defence xiii The Year in Review by the Chief of the SA National Defence Force xv PART1: STRATEGIC DIRECTION Chapter 1 Strategic Direction Introduction 1 Aim 1 Scope of the Annual Report 1 Strategic Profile 2 Alignment with Cabinet and Cluster Priorities 2 Minister of Defence's Priorities for FY2004/05 2 Strategic Focus 2 Functions of the Secretary for Defence 3 Functions of the Chief of the SANDF 3 Parys Resolutions 3 Chapter -

FW De Klerk Foundation Conference on Uniting Behind the Constitution

FW de Klerk Foundation Conference on Uniting Behind the Constitution 2nd February 2013 DR HOLGER DIX, RESIDENT Representative OF THE KONRAD Adenauer Foundation FOR SOUTH Africa, AND FORMER PRESIDENT FW DE KLERK. On Saturday, 2 February 2013, the FW de Klerk Foundation hosted a successful conference at the Protea Hotel President in Bantry Bay, Cape Town. Themed “Uniting Behind the Constitution” and held in conjunction with the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the conference was well attended by members of the public and a large press contingent. The speakers included thought leaders from civil society, business, academia and politics. This publication is a compendium of speeches presented on the day (speeches were transcribed from recordings), each relating to an important facet of the South African Constitution. Each speech was followed by a lively panel discussion, and panelists included: Dr Lucky Mathebula (board member of the FW de Klerk Foundation), John Kane-Berman (CEO of the South African Institute for Race Relations), Adv Paul Hoffman (Director of the Southern African Institute for Accountability), Adv Johan Kruger (Director of the Centre for Constitutional Rights), Dr Theuns Eloff (Vice-Chancellor of North-West University), Adv Johan Kruger SC (Acting Judge and board member of the FW de Klerk Foundation), Michael Bagraim (President of the Cape Chamber of Commerce), Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi (Leader of the IFP) and Paul Graham (Executive Director of the Institute for Democracy in South Africa). UpholdingCelebrating Diversity South -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Inkanyiso OFC 8.1 FM.Fm

21 The suppression of political opposition and the extent of violating civil liberties in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei bantustans, 1960-1989 Maxwell Z. Shamase 1 Department of History, University of Zululand [email protected] This paper aims at interrogating the nature of political suppression and the extent to which civil liberties were violated in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei. Whatever the South African government's reasons, publicly stated or hidden, for encouraging bantustan independence, by the time of Ciskei's independence ceremonies in December 1981 it was clear that the bantustans were also to be used as a more brutal instrument for suppressing opposition. Both Transkei and Ciskei used additional emergency-style laws to silence opposition in the run-up to both self- government and later independence. By the mid-1980s a clear pattern of brutal suppression of opposition had emerged in both bantustans, with South Africa frequently washing its hands of the situation on the grounds that these were 'independent' countries. Both bantustans borrowed repressive South African legislation initially and, in addition, backed this up with emergency-style regulations passed with South African assistance before independence (Proclamation 400 and 413 in Transkei which operated from 1960 until 1977, and Proclamation R252 in Ciskei which operated from 1977 until 1982). The emergency Proclamations 400, 413 and R252 appear to have been retained in the Transkei case and introduced in the Ciskei in order to suppress legal opposition at the time of attainment of self-government status. Police in the bantustans (initially SAP and later the Transkei and Ciskei Police) targeted political opponents rather than criminals, as the SAP did in South Africa. -

EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a FREE SOUTI'ilrn AFRICA S 339 Lafayette Street a Phone: (212) 477-0066 New York, N.Y

E c EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a FREE SOUTI'IlRN AFRICA s 339 Lafayette Street A Phone: (212) 477-0066 New York, N.Y. 10012 Fax: (212} 979 ... 1013 #183 30 July 1997 founded l2 June l956 On Wednesday 16th July I was informed by the Truth Commission that three members of the CCB (The Civil Cooperation Bureau, which was one or the death squads paid for by the military), Mr Joe Verster, Mr. Wouter Basson and Mr Abraham 'Slang' van Zyl, were believed by the Commission to be responsible for the letter bomb attack on me in 1990. They are to be ·subpoenaed to an_in camera hearing by the Truth Commiussion on 17,18 and 19th August. Their subpoena under Section 29 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act means they have not asked for amnesty, and presumably believed that they would not be detected. I congratulated the TRC for discovering those they believed to be responsible. Whilst I did always want to know who was respon.ible it is another burden to come to terms with the reality of three actual human beings who are supposed to have tried to kill me. Following is a the transcript of an article which accurately represents much of my response to these r~velations just a fev hours after I was told. With my praye~s and best wishest Fr. Michael Lapsley, SSY. CAPE TIMES 17th July 1997 FORGIVENESS IS A PACKAGE - LAPSLEY Willem Steenkamp Forgiveness requires not only that perpetrators of gross violations of human rights ask for it, but th8t they also demonstrate their support for restitution and reparation. -

Lesotho | Freedom House

Lesotho | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/lesotho A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 10 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. King Letsie III serves as the ceremonial head of state. The prime minister is head of government; the head of the majority party or coalition automatically becomes prime minister following elections, making the prime minister’s legitimacy largely dependent on the conduct of the polls. Thomas Thabane became prime minister after his All Basotho Convention (ABC) won snap elections in 2017. Thabane, a fixture in the country’s politics, had previously served as prime minister from 2012–14, but spent two years in exile in South Africa amid instability that followed a failed 2014 coup. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The lower house of Parliament, the National Assembly, has 120 seats; 80 are filled through first-past-the-post constituency votes, and the remaining 40 through proportional representation. The Senate—the upper house of Parliament—consists of 22 principal chiefs who wield considerable authority in rural areas and whose membership is hereditary, along with 11 other members appointed by the king and acting on the advice of the Council of State. Members of both chambers serve five- year terms. In 2017, the coalition government of Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili—head of the Democratic Congress (DC)—lost a no-confidence vote. The development triggered the third round of legislative elections held since 2012. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

Military Despatches Vol 24, June 2019

Military Despatches Vol 24 June 2019 Operation Deadstick A mission vital to D-Day Remembering D-Day Marking the 75th anniversary of D-Day Forged in Battle The Katyusha MRLS, Stalin’s Organ Isoroku Yamamoto The architect of Pearl Harbour Thank your lucky stars Life in the North Korean military For the military enthusiast CONTENTS June 2019 Page 62 Click on any video below to view Page 14 How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and Thank your lucky stars techno-speak that few Serving in the North Korean Military outside the military could hope to under- 32 stand. Some of the terms Features were humorous, some Rank Structure 6 This month we look at the Ca- were clever, while others nadian Armed Forces. were downright crude. Top Ten Wartime Urban Legends Ten disturbing wartime urban 36 legends that turned out to be A matter of survival Part of Hipe’s “On the fiction. This month we’re looking at couch” series, this is an 10 constructing bird traps. interview with one of Special Forces - Canada 29 author Herman Charles Part Four of a series that takes Jimmy’s get together Quiz Bosman’s most famous a look at Special Forces units We attend the Signal’s Associ- characters, Oom Schalk around the world. ation luncheon and meet a 98 47 year old World War II veteran. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

John Keene Interviewed by Mike Cadman 19/09/07 Former Regimental Sergeant Major – Rand Light Infantry

1 John Keene interviewed by Mike Cadman 19/09/07 Former Regimental Sergeant Major – Rand Light Infantry TAPE ONE SIDE A Interviewer Can you give me a bit of a background about how you came to be in the military, when you started, just a little sort of thumbnail sketch of your career in the military. John Keene I was born in 1946, which is nine months after the end of the Second World War. And I went to Maritz Brothers College, Inanda. My father had been in the Rand Light Infantry during the Second World War and had been badly wounded at ? My grandfather on my father’s side was a merchant navy captain and he had been responsible for landing Anzac troops in the Dardanelles during the First World War. My mother’s father came out to South Africa in Imperial Military Railways during the Anglo Boer War. So throughout my life I considered that warfare was a natural part of human existence. Through my father I knew all of his comrades in the Rand Light Infantry (RLI), and I’d formed a picture of what the army should be like. At school we were mostly English speaking boys and most of our fathers had also served in the Second World War in one or other of the arms, either the air force, the army or the navy. And the mindset that we had developed at that stage was that our fathers had fought a war for liberation of the human race and that the world offered a lot. -

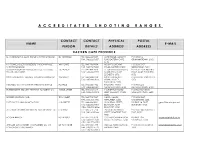

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714