Hugo Alfvén the Symphonies & Rhapsodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra

HansSchmidt-lsserstedt and the StockholmPhilharmonic Orchestra (1957) TheStockholm Philharmonic Orchestra - ALL RECORDINGSMARKED WITH ARE STEREO BIS-CD-421A AAD Totalplayingtime: 71'05 van BEETHOVEN,Ludwig (1770-1827) 23'33 tr SymphonyNo.9 in D minor,Op.125 ("Choral'/, Fourth Movemenl Gutenbuts) 2'.43 l Bars1-91. Conductor.Paavo Berglund Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall 25thMarch 19BB Fadiorecording on tape:Radio Stockholm 1',44 2. Bars92' 163. Conductor:Antal Dor6t Liveconcerl at the StockholmConcert Hall 15thSeptember 1976 Privaterecording on tape.SFO B 276lll 1',56 3 Bars164 '236. Soloist:Sigurd Bjorling, bass Conduclor.Antal Dordti '16th Liveconcert at theStockholm Concert Hall December 1967 Privaterecording on tape.SFO 362 Recordingengineer. Borje Cronstrand 2',27 4 Bars237 '33O' Soloists.Aase Nordmo'Lovberg, soprano, Harriet Selin' mezzo-soprano BagnarUlfung, tenor, Sigurd Biorling' bass Muiit<alisxaSallskapet (chorus master: Johannes Norrby) Conductor.Hans Schmidt-lsserstedt Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall, 19th May 1960 Privaterecording on tape SFO87 Recordingengineer' Borje Cronstrand Bars331 -431 1IAA Soloist:Gosta Bdckelin. tenor MusikaliskaSdllskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norrbv) Conductor:Paul Kletzki Liveconcert at the StockholmConcerl Hall, ist Octoberi95B Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 58/849 -597 Bars431 2'24 MusikaliskaSallskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norroy,l Conductor:Ferenc Fricsay Llverecording at the StockholmConcert Hall,271h February 1957 Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 571199 Bars595-646 3',05 -

Chandos Records Ltd, Chandos House, Commerce Way, Colchester, Essex CO2 8HQ, UK E-Mail: [email protected] Website

CHAN 10271 Book Cover.qxd 7/2/07 1:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 10271(3) X CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10271 Book Cover.qxd 7/2/07 1:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 10271(3) X CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10271 BOOK.qxd 7/2/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) COMPACT DISC ONE Symphony No. 1, Op. 7, FS 16 37:01 in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur 1 I Allegro orgoglioso 10:07 2 II Andante 8:23 3 III Allegro comodo – Andante sostenuto – Tempo I 8:45 4 IV Finale. Allegro con fuoco 9:43 Symphony No. 4, Op. 29, FS 76 ‘The Inextinguishable’ 37:04 Roland Johansson • Lars Hammarteg timpani soloists 5 I Allegro – 11:52 6 II Poco allegretto – 4:59 7 III Poco adagio quasi andante – 10:29 8 IV Allegro – Glorioso – Tempo giusto 9:43 TT 74:13 COMPACT DISC TWO Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29 Department of Copenhagen Library, The Royal Prints and Photographs, Maps, ‘The Four Temperaments’ 35:32 1 I Allegro collerico 10:30 2 II Allegro comodo e flemmatico 5:26 3 III Andante malincolico 12:14 Carl Nielsen 4 IV Allegro sanguineo – Marziale 7:20 3 CHAN 10271 BOOK.qxd 7/2/07 1:14 pm Page 4 Symphony No. 3, Op. 27, FS 60 Symphony No. 6, FS 116 ‘Sinfonia espansiva’ 42:02 ‘Sinfonia semplice’ 34:52 Solveig Kringelborn soprano 7 I Tempo giusto – Allegro passionato – Karl-Magnus Fredriksson baritone Lento ma non troppo – Tempo I (giusto) 13:12 5 I Allegro espansivo 12:44 8 II Humoreske. -

Launy Grøndahl (1886-1960) Un Grand De La Baguette Danoise

ResMusica.com 1 La série des Danois VII. Launy Grøndahl (1886-1960) un grand de la baguette danoise * Jean-Luc CARON * La série des Danois : I : Victor Bendix. Le Danois injustement oublié ; II : Hans Christian Lumbye. Un roi du divertissement au Danemark ; III ; Louis Glass. « Le » post-romantique danois par excellence ; IV : Lange-Müller. Le Danois migraineux ; V : Les Musiciens Danois de L’Age d’Or. Un aperçu. VI ; Fini Henriques. Le sourire du Danemark. VII. Launy Grøndahl. Un grand de la baguette danoise. VIII. Ludolf Nielsen. Le dernier des romantiques danois Dans la grande famille des chefs d’orchestre géniaux… on demande un Danois de premier plan ayant œuvré magistralement pour la musique de son pays. Celle de Carl Nielsen en particulier. Pas uniquement cependant. On tire un nom… C’est Launy Grøndahl. Pour autant ce Grøndahl là n’est pas unique en son genre dans l’art de diriger une formation orchestrale dans le plus méridional des pays nordiques. Plusieurs de ses collègues se sont aussi brillamment illustrés au cours du 20e siècle. On ne fera donc qu’en citer certains afin de les tirer très ponctuellement de l’oubli total dans lequel ils reposent depuis si (trop) longtemps. Il s’agit principalement de musiciens de la trempe d’Erik Tuxen, de Thomas Jensen, Carl Gariguly, John Frandsen, Georg Høeberg, Mogens Woldike, J. Hye-Knudsen, Egisto Tango, Emil Reesen, J.G. Felumb et F. Schnedler-Petersen. Nous proposons pour chacun d’entre eux une très brève présentation biographique à la fin de cet article. 1 Consultable à http://www.resmusica.com/dossier_28_les_compositeurs_du_nord_la_serie_des_danois.html Launy Grøndahl Mais revenons à Launy Grøndahl, l’homme aux deux casquettes. -

CHAN 10287 Front.Qxd 14/9/06 12:07 Pm Page 1

CHAN 10287 front.qxd 14/9/06 12:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 10287 X CHAN 10287 BOOK.qxd 14/9/06 12:02 pm Page 2 Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 27:22 1 1 Allegro moderato e marcato – Vivace – Più lento – Tempo I – Vivace – Tempo I – Presto 5:30 in G major • in G-Dur • en sol majeur 2 Lebrecht Music & Music Lebrecht Arts Library Photo 2 Allegretto grazioso – Più mosso – Tempo I 5:16 in A major • in A-Dur • en la majeur 3 3 Allegro giocoso 5:38 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur 4 4 Andante – Allegro molto e risoluto – Più tranquillo – Tempo I – Presto 10:44 in A minor • in a-Moll • en la mineur Six Songs for voice and orchestra 28:54 5 I Solveig’s Song 5:10 Solveigs Sang Un poco andante 6 II Solveig’s Cradle Song 4:23 Solveigs Vuggevise Lento 7 III From Monte Pincio 4:58 Fra Monte Pincio Andante molto Edvard Grieg 3 CHAN 10287 BOOK.qxd 14/9/06 12:02 pm Page 4 Grieg: Six Songs etc. 8 IV A Swan 2:30 Today the majority of Grieg’s compositions the use of the word ‘symphonic’, Grieg’s En Svane reside outside the realm of the standard Op. 64 relies more on dance and folk-like concert repertoire. Although his reputation material. Andante ben tenuto rests on relatively few pieces, such as the The first dance, Allegro moderato e 9 V Springtide 7:20 Piano Concerto, the Peer Gynt music and the marcato, in G major begins and ends with a Våren Holberg Suite, this is no indication of the lively, rhythmic idea. -

CV För Einar Nielsen 1962-2018

Curriculum Vitae för Einar Nielsen 1960-62 Turnéer med bl.a. The Syncopaters och Kansas City Stompers i Danmark och Tyskland 1963 Fast assistans i Sønderjyllands Symfoniorkester 1963-69 (konstnärlig ledare Carl von Garaguly) 1964 Studerande vid Vestjysk Musikkonservatorium, lärare Olaf Jensen, Sønderjyllands Symfoniorkester Pukslagare i Vestjysk Symfoniorkester 1964-69 1968 Deltagande i Skandinaviske sommarkurser för ny musik i Göteborg Deltagande i kurs med Witold Lutoslawski, komponist, på DJM 1969 Diplomexamen Studerande vid Det jyske Musikkonservatorium (DJM) i solistklassen, lärare: Bent Lylloff Fast assistans i Århus Symfoniorkester 1969-70 Deltagande i kurs med Joe Morello, trommesæt, USA 1970 Medverkan vid UNM i Stockholm Turnéer med Den jyske Opera 1970-89 Fast anställning som slagverksspelare och alternerande pukslagare i Ålborg Symfoniorkester 1970-74 Turné till Tjekkoslovakiet 1971 Studier hos professor Christoph Caskel, slagverk, Staatliche Hochschule für Musik, Köln, 1971-76 Gästspel med Den kgl. Ballet och Stockholms Operan Turné till Vesttyskland, Dortmund 1972 Debut från solistklassen i Århus Studerande på pedagoglinjen vid DJM Gästspel med Den Kgl. Ballet Deltagande i kurs med Lars Johan Werle, komponist, på Nordjysk Musikkonservatorium 1 1973 Assisterande lärare vid DJM Turné till Poznan, Warzava, Krakow och Prag Deltagande i kurs med Saul Goodman, pukor, New York Philharmonic, på DJM Gästspel med Den kgl. Opera och Bolshojballetten Solist med Sønderjyllands Symfoniorkester och Ålborg Symfoniorkester Arrangör av utställning -

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS from the 19Th

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers R-Z JAAN RÄÄTS (b. 1932, ESTONIA) Born in Tartu. He studied piano at the Tartu Music High School and graduated from the Tallinn Conservatory as a composition student of Mart Saar and Heino Eller. Subsequently, he worked as a recording engineer at the Estonian Radio, chief editor of music programs, and then chief director and music manager of the Estonian Television and chairman of the Estonian Composers' Union. Most significantly, he has taught composition at the Estonian Academy of Music and his pupils include many of the most prominent Estonian composers of the present generation. He has composed orchestral, chamber, solo instrumental, choral, vocal and electronic music as well as film scores. His other orchestral works include Concerto for Chamber Orchestra No. 2 for Strings, Op.78 (1987) and the following concertante works: Piano Concertos Nos. 1, Op. 34 (1968) and 3, Op. 83 (1990), Concerto for Piano and Chamber Orchestra, Op. 41 (1971), Concerto for Piano, Four Hands and Orchestra, Op. 89 (1992), Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra, Op. 77 (1986), Concerto for Two Pianos, String Orchestra and Percussion, Op. 22 (1963), Concerto for Piano Trio and Orchestra, Op.127 (2006), Mini Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (2000), Violin Concerto, Op. 51 (1974), Concerto for Violin and Chamber Orchestra No. 3, Op. 96 (1995), Cello Concerto No.1, Op. 43 (1971, recomposed as Op.59 (1977), Cello Concerto No. 3, Op. 99 (1997), Concerto for Cello and Chamber Orchestra No. -

The Norwegian Hardanger Fiddle in Classical Music

STUDIA INSTRUMENTORUM MUSICAE POPULARIS XVI Tarptautinės tradicinės muzikos tarybos Liaudies muzikos instrumentų tyrimų grupės XVI tarptautinės konferencijos straipsniai / ICTM Study Group on Folk Musical Instruments Proceedings from the 16th International Meeting ISSN 1392–2831 Tautosakos darbai XXXII 2006 THE NORWEGIAN HARDANGER FIDDLE IN CLASSICAL MUSIC BJØRN AKSDAL The Norwegian Council for Traditional Music and Dance S u b j e c t: The interrelationship between a traditional instrument and modern art music in Norway. P u r p o s e o f s t u d y: To reveal how the special status of a folk instrument has influenced the development of art music from the period of national romanticism up to today. M e t h o d s: Descriptive, historical. K e y w o r d s: National romanticism, ideology, classical music, instrument history, con- temporary music. The Roots of the Hardanger Fiddle The Norwegian Hardanger fiddle, with its rich decorations and sympathetic strings, dates back to at least the mid-17th century. The oldest surviving fiddle is the so-called Jaastad fiddle from 1651, made by the local sheriff in Ullensvang, Hardanger, Ole Jonsen Jaastad (1621–1694). This is a rather small instrument with a very curved body, supplied with two sympathetic strings. We believe that this and other similar fiddles which are found especially in Western Norway and in the Telemark area could be descendants from the Medieval fiddles in Scandinavia. To put sympathetic strings on bowed instruments was probably an impulse from the British Isles reaching the Hardanger region early in the 17th century. -

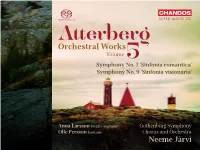

Orchestral Works Volume 5 Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Atterberg Orchestral Works Volume 5 Symphony No. 7 ‘Sinfonia romantica’ Symphony No. 9 ‘Sinfonia visionaria’ Anna Larsson mezzo-soprano Gothenburg Symphony Olle Persson baritone Chorus and Orchestra Neeme Järvi Private photograph courtesy of the Estate of Kurt Atterberg Kurt Atterberg, at work on Symphony No. 9, Guéthary, France, 1955 Kurt Atterberg (1887 – 1974) Orchestral Works, Volume 5 Symphony No. 7, Op. 45 ‘Sinfonia romantica’ (1941 – 42) 28:43 1 I Drammatico. Lento – Molto vivo – Andante – Andante molto tranquillo – Molto vivo – Cantando – Lento – Vivacissimo 12:39 2 II Semplice. Andante – Un poco più lento – A tempo I – Tranquillo 8:35 3 III Feroce. Allegro – L’istesso tempo, pesante – (Un poco meno mosso) – (Tranquillo) – (Con moto) – (Tempo I) – Animando al fine 7:22 3 Symphony No. 9, Op. 54 ‘Sinfonia visionaria’ (1955 – 56)* 34:18 in modo di rondo espansivo for Mezzo-soprano, Baritone, Chorus, and Orchestra after Völuspá (c. 950 – 1350), from the Icelandic Poetic Edda (Valans Visdom / The Wisdom [or Prophesy] of the Vala [or Seeress]) 4 Adagio – 2:16 5 Andante. Barden: ‘Heid hon hette, till vad hus hon kom’ – Tranquillo. Valan: ‘Varom frågen I mig?’ – [Andante.] Barden: ‘Härfader gav henne halsguld och ringar’ – 2:12 6 Con moto. Valan: ‘Jag jättarna minns, i urtid avlade’ – Poco tranquillo. Valan: ‘Gapande svalg fanns men gräs icke’ – [Con moto.] Valan: ‘I åldrarnas ursprung, när Ymer levde’ – Poco tranquillo. Valan: ‘stjärnorna ej var de skimra skulle’ – [Con moto.] Valan: ‘Söner till Bur då lyfte landen’ – Poco meno mosso. Kör, Valan: ‘Då drogo de mäktige till sina domaresäten’ – Tranquillo. Barden: ‘Hon såg vida och än vidare i världar alla’ – 3:38 7 Valan: ‘En ask ser jag stånda, den Yggdrasil heter’ – Molto tranquillo – Con moto. -

Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland)

FINNISH & BALTIC SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Jean Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland) Born in Hämeenlinna. Slated for a career in law, he left the University of Helsingfors (now Helsinki) to study music at the Helsingfors Conservatory (now the Sibelius Academy). His teachers were Martin Wegelius for composition and Mitrofan Vasiliev and Hermann Csilag. Sibelius continued his education in Berlin studying counterpoint and fugue with Albert Becker and in Vienna for composition and orchestration with Robert Fuchs and Karl Goldmark. He initially aimed at being a violin virtuoso but composition soon displaced that earlier ambition and he went on to take his place as one of the world's greatest composer who not only had fame in his own time but whose music lives on without any abatement. He composed a vast amount of music in various genres from opera to keyboard pieces, but his orchestral music, especially his Symphonies, Violin Concertos, Tone Poems and Suites, have made his name synonymous with Finnish music. Much speculation and literature revolves around Sibelius so- called "Symphony No. 8." Whether he actually wrote it and destroyed it or never wrote it all seems less important than the fact that no such work now exists. Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 (1899) Maurice Abravanel/Utah Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) MUSICAL CONCEPTS MC 132 (3 CDs) (2012) (original release: VANGUARD SRV 381-4 {4 LPs}) (1978) Nikolai Anosov/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra MELODIYA D 02952-3 (LP) (1956) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Philharmonia Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

4902450-Fc904d-BIS-1402-04 Booklet X.Pdf

BIS-CD-1402/1404 STEREO D D D /AAD Total playing time: 331'20 TUBIN, Eduard (1905-1982) BIS-CD-1402 D D D Playing time: 63'20 Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1931-34) (STIM) 32'21 1 I. Adagio – Allegro feroce 13'40 2 II. Allegretto moderato 9'07 3 III. Sostenuto assai quasi largo e poco maestoso 9'14 Orchestral soloists: Bernt Lysell, violin; Björn Sjögren, viola; Ola Karlsson, cello Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra Symphony No. 5 in B minor (1946) (Körlings) 30'15 4 I. Allegro energico 9'45 5 II. Andante 9'16 6 III. Allegro assai 10'53 Bamberg Symphony Orchestra BIS-CD-1403 D D D Playing time: 64'01 Symphony No. 2, ‘The Legendary’ (1937-38) (STIM) 31'45 1 I. Légendaire 10'04 2 II. Sostenuto assai, grave e funebre 7'01 3 III. Tempestoso, ma non troppo allegro (quasi toccata) 14'30 Orchestral soloists: Bernt Lysell, violin; Björn Sjögren, viola; Bengt Forsberg, piano Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra 2 BIS-CD-1404 B AA D Playing time: 65'24 Symphony No. 4 in A major, ‘Sinfonia lirica’ (1943/78) (STIM) 35'32 1 I. Molto moderato 10'39 2 II. Allegro con anima 7'15 3 III. Andante un poco maestoso 7'57 4 IV. Allegro 9'12 Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Recorded at a public concert at the Grieg Hall, Bergen, on 5th November 1981. Symphony No. 9, ‘Sinfonia semplice’ (1969) (STIM) 22'22 5 I. Adagio 11'03 6 II. Adagio, lento 11'08 Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra 7 Toccata (1937) (Körlings) 5'38 Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra BIS-CD-1404 C D D D Playing time: 75'49 Symphony No. -

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS from the 19Th

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-H TORSTEIN AAGARD-NILSON (b.1964, NORWAY) Born in Oslo. He studied at the Bergen Conservatory and then taught contemporary classical music at this school. He has also worked as a conductor and director of music festivals. He has written works for orchestra, chamber ensemble, choir, wind and brass band. His catalogue also includes the following: Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1995-6), Concerto for Trumpet and String Orchestra "Hommage" (1996), Trombone Concerto No. 1 (1998), Concerto for Euphonium and Orchestra "Pierrot´s Lament" (2000) and The Fourth Angel for Trumpet and Sinfonietta (1992-2000). Trombone Concerto No. 2 "Fanfares and Fairytales" (2003-5) Per Kristian Svensen (trombone)/Terje Boye Hansen/Malmö Symphony Orchestra ( + Hovland: Trombone Concerto, Amdahl: Elegy for Trombone, Piano and Orchestra and Plagge: Trombone Concerto) TWO-I 35 (2007) Tuba Concerto "The Cry of Fenrir" (1997, rev. 2003) Eirk Gjerdevik (tuba)/Bjorn Breistein/Pleven Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Koch: Tuba Concerto and Vaughan Williams: Tuba Concerto) LAWO CLASSICS LWC 1039 (2012) HANS ABRAHAMSEN (b. 1952, DENMARK) Born in Copenhagen. He played the French horn at school and had his first lessons in composition with Niels Viggo Bentzon. Then he went on to study music theory at The Royal Danish Academy of Music where his composition teachers included Per Nørgård and Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen. Later on, he had further composition studies with György Ligeti. In 1995, he was appointed assistant professor in composition and orchestration at The Royal Danish Academy of Music, Copenhagen. -

SCANDINAVIAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

SCANDINAVIAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman CARL NIELSEN (1865-1931), DENMARK Born in Sortelung (Nørre Lyndelse), near Odense. He learned the violin and piano as a child and began composing as well. After learning how to play brass instruments, he got a job as a as a bugler and trombonist in an Odense band. His formal musical education was at the Copenhagen Music Conservatory where he studied the violin with Valdemar Tofte, music theory with Orla Rosenhoff and music history with Niels Gade. He was a violinist with the orchestra of the Royal Theater in Copenhagen and earned some extra income as a teacher before making his breakthrough as a composer with his Suite for Strings. After receiving a state pension, he often appeared as a conductor but he was able to devote his musical career mostly to composition. He is uncontestedly seen as Denmark's greatest composer, whose cycle of Symphonies reached world prominence and whose other major works, the Concertos for Violin, Clarinet and Flute, his 2 operas and various chamber works are of the highest quality. Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 7 (1890-2) Paavo Berglund/Royal Danish Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4 ,5 and 6) RCA RED SEAL 88875052182 (3 CDs) (2015) (original CD release: RCA VICTOR RED SEAL 7701-2) (1988) Herbert Blomstedt/Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, At the Bier of a Young Artist and Bohemian-Danish Folk Melodies) EMI CLASSICS TRIPLE 500829-2 (3 CDs) (2007) (original release: HMV SLS 5027 {8 LPs}) (1975) Herbert Blomstedt/San Francisco Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos.