The Norwegian Hardanger Fiddle in Classical Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSLO – BERGEN Ward Group

OSLO – BERGEN Ward Group 10th of June 2018 Oslo (-/L/D) 12.20 Arrival at Gardermoen Airport Oslo, where we meet the Norwegian guide and bus driver. Transfer to Oslo. Lunch City Sight Seeing in Oslo incl. Vigeland park and the Fram Museum. Oslo is the oldest of the Scandinavian capitals, and its history goes back l000 years, to the time when the first settlements were built at the inlet of the Oslo fjord. Oslo has about 600 000 inhabitants. Dinner and night at Scandic Holmenkollen Park hotel in Oslo 11th of June 2018 Oslo – Lillehammer (B/L/D) After breakfast departure to Lillehammer En route farm visit and visit to Visit to the breeding organization for Norwegian Red (NRF),a Norwegian cooperative organization owned by 11.000 Norwegian dairy farmers. Lunch en route Dinner and night at Clarion Collection hotel Hammer in Lillehammer 12th of June 2018 Lillehammer – Lom (B/L/D) Breakfast at the hotel In Lillehammer we will have a short stop at the Olympic facilities where the Olympic Winter Games were held in 1994, where after we will visit Maihaugen Open Air museum depicting Norwegian farm life over centuries. Lunch at Maihaugen Postboks 98 [email protected] N-2684 Vågå www.scandinaviatours.no Tel. +47 99 69 38 54 OSLO – BERGEN Ward Group Departure to Lom Farm visit en route Dinner and night at Fossheim Hotel in the lovely village Lom (Web site only in Norwegian) 13th of June 2018 Lom - Flåm – Hardanger (B/L/D) After breakfast we'II head for Ulvik, ca 285 km. -

The Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra

HansSchmidt-lsserstedt and the StockholmPhilharmonic Orchestra (1957) TheStockholm Philharmonic Orchestra - ALL RECORDINGSMARKED WITH ARE STEREO BIS-CD-421A AAD Totalplayingtime: 71'05 van BEETHOVEN,Ludwig (1770-1827) 23'33 tr SymphonyNo.9 in D minor,Op.125 ("Choral'/, Fourth Movemenl Gutenbuts) 2'.43 l Bars1-91. Conductor.Paavo Berglund Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall 25thMarch 19BB Fadiorecording on tape:Radio Stockholm 1',44 2. Bars92' 163. Conductor:Antal Dor6t Liveconcerl at the StockholmConcert Hall 15thSeptember 1976 Privaterecording on tape.SFO B 276lll 1',56 3 Bars164 '236. Soloist:Sigurd Bjorling, bass Conduclor.Antal Dordti '16th Liveconcert at theStockholm Concert Hall December 1967 Privaterecording on tape.SFO 362 Recordingengineer. Borje Cronstrand 2',27 4 Bars237 '33O' Soloists.Aase Nordmo'Lovberg, soprano, Harriet Selin' mezzo-soprano BagnarUlfung, tenor, Sigurd Biorling' bass Muiit<alisxaSallskapet (chorus master: Johannes Norrby) Conductor.Hans Schmidt-lsserstedt Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall, 19th May 1960 Privaterecording on tape SFO87 Recordingengineer' Borje Cronstrand Bars331 -431 1IAA Soloist:Gosta Bdckelin. tenor MusikaliskaSdllskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norrbv) Conductor:Paul Kletzki Liveconcert at the StockholmConcerl Hall, ist Octoberi95B Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 58/849 -597 Bars431 2'24 MusikaliskaSallskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norroy,l Conductor:Ferenc Fricsay Llverecording at the StockholmConcert Hall,271h February 1957 Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 571199 Bars595-646 3',05 -

Beethoven and Banjos - an Annual Musical Celebration for the UP

Beethoven and Banjos - An Annual Musical Celebration for the UP Beethoven and Banjos 2018 festival is bringing Nordic folk music and some very unique instruments to the Finnish American Heritage Center in Hancock, Michigan. Along with the musicians from Decoda (Carnegie Hall’s resident chamber group) we are presenting Norwegian Hardanger fiddler Guro Kvifte Nesheim and Swedish Nyckelharpist Anna Gustavsson. Guro Kvifte Nesheim grew up in Oslo, Norway, and started playing the Hardanger fiddle when she was seven years old. She has learned to play the traditional music of Norway from many great Hardanger fiddle players and has received prizes for her playing in national competitions for folk music. In 2013 she began her folk music education in Sweden at the Academy of Music and Drama in Gothenburg. Guro is composing a lot of music, and has a great interest and love for the old music traditions of Norway and Sweden. In 2011 she went to the world music camp Ethno and was bit by the “Ethno-bug”. Since then she has attended many Ethno Camps as a participant and leader, and setup Ethno Norway with a team of fellow musicians. In spring 2015 she worked at the Opera House of Gothenburg with the dance piece “Shadowland”. The Hardanger fiddle is a traditional instrument from Norway. It is called the Hardanger Fiddle because the oldest known Hardanger Fiddle, made in 1651, was found in the area Hardanger. The instrument has beautiful decorations, traditional rose painting, mother-of-pearl inlays and often a lion’s head. The main characteristic of the Hardanger Fiddle is the sympathetic strings that makes the sound very special – it’s like an old version of a speaker that amplifies the sound. -

Regional Kystsoneplan for Sunnhordland Og Ytre Hardanger

Rapporttittel 1 Regional kystsoneplan for Sunnhordland og ytre Hardanger Planforslag 25.08.2017 – vedlegg til Fylkestinget oktober 2017 Førstesidebilete: Svein Andersland, Multiconsult AS – 2 – Innhald 1 Innleiing ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Hovudmål ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 3 Berekraftig kystsoneplanlegging .................................................................................................................10 Delmål berekraftig kystsoneforvaltning ...................................................................................................10 Marint naturgrunnlag ...............................................................................................................................11 Fiskeri ......................................................................................................................................................16 Andre bruksinteresser .............................................................................................................................18 Friluftsliv...................................................................................................................................................19 Landskap og kulturminne ........................................................................................................................20 -

WEST NORWEGIAN FJORDS UNESCO World Heritage

GEOLOGICAL GUIDES 3 - 2014 RESEARCH WEST NORWEGIAN FJORDS UNESCO World Heritage. Guide to geological excursion from Nærøyfjord to Geirangerfjord By: Inge Aarseth, Atle Nesje and Ola Fredin 2 ‐ West Norwegian Fjords GEOLOGIAL SOCIETY OF NORWAY—GEOLOGICAL GUIDE S 2014‐3 © Geological Society of Norway (NGF) , 2014 ISBN: 978‐82‐92‐39491‐5 NGF Geological guides Editorial committee: Tom Heldal, NGU Ole Lutro, NGU Hans Arne Nakrem, NHM Atle Nesje, UiB Editor: Ann Mari Husås, NGF Front cover illustrations: Atle Nesje View of the outer part of the Nærøyfjord from Bakkanosi mountain (1398m asl.) just above the village Bakka. The picture shows the contrast between the preglacial mountain plateau and the deep intersected fjord. Levels geological guides: The geological guides from NGF, is divided in three leves. Level 1—Schools and the public Level 2—Students Level 3—Research and professional geologists This is a level 3 guide. Published by: Norsk Geologisk Forening c/o Norges Geologiske Undersøkelse N‐7491 Trondheim, Norway E‐mail: [email protected] www.geologi.no GEOLOGICALSOCIETY OF NORWAY —GEOLOGICAL GUIDES 2014‐3 West Norwegian Fjords‐ 3 WEST NORWEGIAN FJORDS: UNESCO World Heritage GUIDE TO GEOLOGICAL EXCURSION FROM NÆRØYFJORD TO GEIRANGERFJORD By Inge Aarseth, University of Bergen Atle Nesje, University of Bergen and Bjerkenes Research Centre, Bergen Ola Fredin, Geological Survey of Norway, Trondheim Abstract Acknowledgements Brian Robins has corrected parts of the text and Eva In addition to magnificent scenery, fjords may display a Bjørseth has assisted in making the final version of the wide variety of geological subjects such as bedrock geol‐ figures . We also thank several colleagues for inputs from ogy, geomorphology, glacial geology, glaciology and sedi‐ their special fields: Haakon Fossen, Jan Mangerud, Eiliv mentology. -

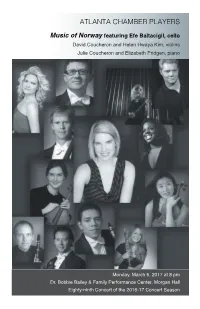

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

Christianialiv

Christianialiv Works from Norway’s Golden Age of wind music Christianialiv The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces The second half of the 19th century is often called the “Golden Age” of Norwegian music. The reason lies partly in the international reputations established by Johan Svendsen and Edvard Grieg, but it also lies in the fact that musical life in Norway, at a time of population growth and economic expansion, enjoyed a period of huge vitality and creativity, responding to a growing demand for music in every genre. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces (to use its modern name) played a key role in this burgeoning musical life not just by performing music for all sections of society, but also by discovering and fostering musical talent in performers and composers. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen and Alfred Evensen, whose music we hear on this album, can therefore be called part of the band’s history. Siste del av 1800-tallet er ofte blitt kalt «gullalderen» i norsk musikk. Det skyldes ikke bare Svendsens og Griegs internasjonale posisjon, men også det faktum at musikklivet i takt med befolkningsøkning og økonomiske oppgangstider gikk inn i en glansperiode med et sterkt behov for musikk i alle sjangre. I denne utviklingen spilte Forsvarets stabsmusikkorps en sentral rolle, ikke bare som formidler av musikkopplevelser til alle lag av befolkningen, men også som talentskole for utøvere og komponister. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen og Alfred Evensen er derfor en del av korpsets egen musikkhistorie. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces / Ole Kristian Ruud Recorded in DXD 24bit/352.8kHz 5.1 DTS HD MA 24/192kHz 2.0 LPCM 24/192kHz + MP3 and FLAC EAN13: 7041888519027 q e 101 2L-101-SABD made in Norway 20©14 Lindberg Lyd AS 7 041888 519027 Johan Svendsen (1840-1911) Symfoni nr. -

The Fiddle Traditions the Violin Comes to Norway It Is Believed That The

The fiddle traditions The violin comes to Norway It is believed that the violin came to that violins from this period were Norway in the middle of the 1600s brought home by, amongst others, from Italy and Germany. This was Norwegian soldiers who fought in probably as a result of upper class wars in Europe. music activities in the towns. But, much suggests that fiddle playing was known in the countryside before this. Already around 1600 ‘farmer fiddles’ are described in old sources, and named fiddlers are also often encountered. We know of the Hardanger fiddle from the middle of the 1600s, which implies that a fiddle-making industry was already established in the countryside before the violin was popular in the Norwegian towns. Rural craftsmen in Norway must have acquired knowledge about this new instrument from 1500s Italy and been inspired by it. One can imagine From 1650 onwards, the violin quickly became a popular instrument throughout the whole of the country. We have clear evidence of this in many areas – from Finnmark, the rural areas of the West Coast and from inland mountain and valley districts. The fiddle, as it was also called, was the pop instrument of its day. There exist early descriptions as to how the farming folk amused themselves and danced to fiddle music. In the course of the 1700s, its popularity only increased, and the fiddle was above all used at weddings and festive occasions. Fiddlers were also prominent at the big markets, and here it was possible to find both fiddles and fiddle strings for sale. -

572095 Bk Tveitt 13/10/08 12:19 Page 12

572095 bk Tveitt 13/10/08 12:19 Page 12 WIND BAND CLASSICS Geirr TVEITT Sinfonia di Soffiatori • Sinfonietta di Soffiatori Selections from A Hundred Hardanger Tunes The Royal Norwegian Navy Band • Bjarte Engeset Geirr Tveitt on camel, Sahara Desert, 1953 Photo © Gyri and Haoko Tveitt 8.572095 12 572095 bk Tveitt 13/10/08 12:19 Page 2 Geirr TVEITT (1908-1981) Music for Wind Instruments Sinfonia di Soffiatori 16:01 Hundrad Hardingtonar 1 I. Moderato 4:43 (A Hundred Hardanger Tunes), 2 II. Alla marcia 3:56 3 III. Andante 7:22 Op. 151 (transcriptions by Stig Nordhagen) 4 Prinds Christian Frederiks Honnørmarch Suite No. 2: Femtan Fjelltonar (15 Mountain Songs) 5:45 (Prince Christian Fredrick’s @ No. 20: Med sterkt Øl te Fjells March of Honour) 3:19 (Bringing strong Ale into the Mountains) 1:23 # No. 23: Rjupo pao Folgafodne 5 Det gamle Kvernhuset (The Song of the Snow Grouse (The Old Mill on the Brook), on the Folgafodne Glacier) 3:04 Op. 204 3:03 $ No. 29: Fjedlmansjento upp i Lid (The Mountain Girl skiing Downhill) 1:18 6 Hymne til Fridomen Suite No. 4: Brudlaupssuiten (Hymn to Freedom) 3:05 (Wedding Suite) 6:30 % No. 47: Friarføter (Going a-wooing) 1:32 Sinfonietta di Soffiatori, Op. 203 12:40 ^ No. 52: Graot og Laott aot ain Baot 7 I. Intonazione d’autunno: Lento – (Tears and Laughter for a Boat) 1:37 Poco più mosso – Tempo I 4:00 & No. 60: Haringøl (Hardanger Ale) 3:20 8 II. Ricordi d’estate: Tempo moderato di springar 2:13 9 III. -

Chandos Records Ltd, Chandos House, Commerce Way, Colchester, Essex CO2 8HQ, UK E-Mail: [email protected] Website

CHAN 10271 Book Cover.qxd 7/2/07 1:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 10271(3) X CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10271 Book Cover.qxd 7/2/07 1:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 10271(3) X CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10271 BOOK.qxd 7/2/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) COMPACT DISC ONE Symphony No. 1, Op. 7, FS 16 37:01 in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur 1 I Allegro orgoglioso 10:07 2 II Andante 8:23 3 III Allegro comodo – Andante sostenuto – Tempo I 8:45 4 IV Finale. Allegro con fuoco 9:43 Symphony No. 4, Op. 29, FS 76 ‘The Inextinguishable’ 37:04 Roland Johansson • Lars Hammarteg timpani soloists 5 I Allegro – 11:52 6 II Poco allegretto – 4:59 7 III Poco adagio quasi andante – 10:29 8 IV Allegro – Glorioso – Tempo giusto 9:43 TT 74:13 COMPACT DISC TWO Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29 Department of Copenhagen Library, The Royal Prints and Photographs, Maps, ‘The Four Temperaments’ 35:32 1 I Allegro collerico 10:30 2 II Allegro comodo e flemmatico 5:26 3 III Andante malincolico 12:14 Carl Nielsen 4 IV Allegro sanguineo – Marziale 7:20 3 CHAN 10271 BOOK.qxd 7/2/07 1:14 pm Page 4 Symphony No. 3, Op. 27, FS 60 Symphony No. 6, FS 116 ‘Sinfonia espansiva’ 42:02 ‘Sinfonia semplice’ 34:52 Solveig Kringelborn soprano 7 I Tempo giusto – Allegro passionato – Karl-Magnus Fredriksson baritone Lento ma non troppo – Tempo I (giusto) 13:12 5 I Allegro espansivo 12:44 8 II Humoreske. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

Conference Program 2011

Grieg Conference in Copenhagen 11 to 13 August 2011 CONFERENCE PROGRAM 16.15: End of session Thursday 11 August: 17.00: Reception at Café Hammerich, Schæffergården, invited by the 10.30: Registration for the conference at Schæffergården Norwegian Ambassador 11.00: Opening of conference 19.30: Dinner at Schæffergården Opening speech: John Bergsagel, Copenhagen, Denmark Theme: “... an indefinable longing drove me towards Copenhagen" 21.00: “News about Grieg” . Moderator: Erling Dahl jr. , Bergen, Norway Per Dahl, Arvid Vollsnes, Siren Steen, Beryl Foster, Harald Herresthal, Erling 12.00: Lunch Dahl jr. 13.00: Afternoon session. Moderator: Øyvind Norheim, Oslo, Norway Friday 12 August: 13.00: Maria Eckhardt, Budapest, Hungary 08.00: Breakfast “Liszt and Grieg” 09.00: Morning session. Moderator: Beryl Foster, St.Albans, England 13.30: Jurjen Vis, Holland 09.00: Marianne Vahl, Oslo, Norway “Fuglsang as musical crossroad: paradise and paradise lost” - “’Solveig`s Song’ in light of Søren Kierkegaard” 14.00: Gregory Martin, Illinois, USA 09.30: Elisabeth Heil, Berlin, Germany “Lost Among Mountain and Fjord: Mythic Time in Edvard Grieg's Op. 44 “’Agnete’s Lullaby’ (N. W. Gade) and ‘Solveig’s Lullaby’ (E. Grieg) Song-cycle” – Two lullabies of the 19th century in comparison” 14.30: Coffee/tea 10.00: Camilla Hambro, Åbo, Finland “Edvard Grieg and a Mother’s Grief. Portrait with a lady in no man's land” 14.45: Constanze Leibinger, Hamburg, Germany “Edvard Grieg in Copenhagen – The influence of Niels W. Gade and 10.30: Coffee/tea J.P.E. Hartmann on his specific Norwegian folk tune.” 10.40: Jorma Lünenbürger, Berlin, Germany / Helsinki, Finland 15.15: Rune Andersen, Bjästa, Sweden "Grieg, Sibelius and the German Lied".