AN ANALYSIS of ELDER FINANCIAL EXPLOITATION: FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS SHIRKING THEIR LEGAL OBLIGATIONS to PREVENT, DETECT, and REPORT THIS “HIDDEN” CRIME Jesse R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police Its Police

DePaul Journal for Social Justice Volume 10 Issue 1 Winter 2017 Article 2 February 2017 Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police Elizabeth J. Andonova Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Social Welfare Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth J. Andonova, Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police, 10 DePaul J. for Soc. Just. (2017) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andonova: Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police I Author: Elizabeth J. Andonova Source: The National Lawyers Guild Source Citation: 73 LAW. GUILD REV. 2 (2016) Title: Cycle of Misconduct: How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police the Police Republication Notice This article is being republished with the express consent of The National Lawyers Guild. This article was originally published in the National Lawyers Guild Summer 2016 Review, Volume 73, Number 2. That document can be found at: https://www.nlg.org/nlg-review/wp- content/uploads/sites/2/2016/11/NLGRev-73-2-final-digital.pdf. The DePaul Journal for Social Justice would like to thank the NLG for granting us the permission to republish this article. -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

2014/2015 Omium Gatherum & Newsletter

2014-2015 Issue 19 omnium gatherum & newsletter ~ i~ COMMUNITY OF WRITERS AT SQUAW VALLEY GOT NEWS? Do you have news you would OMNIUM GATHERUM & NEWSLETTER like us to include in the next newsletter? The 2014-15, Issue 19 Omnium is published once a year. We print publishing credits, awards and similar new Community of Writers at Squaw Valley writing-related achievements, and also include A Non-Profit Corporation #629182 births. News should be from the past year only. P.O. Box 1416, Nevada City, CA 95959 Visit www.squawvalleywriters.org for more E-mail: [email protected] information and deadlines. www.squawvalleywriters.org Please note: We are not able to fact-check the submitted news. We apologize if any incorrect BOARD OF DIRECTORS information is published. President James Naify Vice President Joanne Meschery NOTABLE ALUMNI: Visit our Notable Alumni Secretary Jan Buscho pages and learn how to nominate yourself or Financial OfficerBurnett Miller a friend: Eddy Ancinas http://squawvalleywriters.org/ René Ancinas NotableAlumniScreen.html Ruth Blank http://squawvalleywriters.org/ Jan Buscho NotableAlumniWriters.html Max Byrd http://squawvalleywriters.org/ Alan Cheuse NotableAlumniPoets.html Nancy Cushing Diana Fuller ABOUT OUR ADVERTISERS The ads which Michelle Latiolais appear in this issue represent the work of Edwina Leggett Community of Writers staff and participants. Lester Graves Lennon These ads help to defray the cost of the Carlin Naify newsletter. If you have a recent or forthcom- Jason Roberts ing book, please contact us about advertising Christopher Sindt in our next annual issue. Contact us for a rate sheet and more information: (530) 470-8440 Amy Tan or [email protected] or visit: John C. -

Freedom of Religion and the Church of Scientology in Germany and the United States

SHOULD GERMANY STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE OCTOPUS? FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY IN GERMANY AND THE UNITED STATES Religion hides many mischiefs from suspicion.' I. INTRODUCTION Recently the City of Los Angeles dedicated one of its streets to the founder of the Church of Scientology, renaming it "L. Ron Hubbard Way." 2 Several months prior to the ceremony, the Superior Administrative Court of Miinster, Germany held that Federal Minister of Labor Norbert Bluim was legally permitted to continue to refer to Scientology as a "giant octopus" and a "contemptuous cartel of oppression." 3 These incidents indicate the disparity between the way that the Church of Scientology is treated in the United States and the treatment it receives in Germany.4 Notably, while Scientology has been recognized as a religion in the United States, 5 in Germany it has struggled for acceptance and, by its own account, equality under the law. 6 The issue of Germany's treatment of the Church of Scientology has reached the upper echelons of the United States 1. MARLOWE, THE JEW OF MALTA, Act 1, scene 2. 2. Formerly known as Berendo Street, the street links Sunset Boulevard with Fountain Avenue in the Hollywood area. At the ceremony, the city council president praised the "humanitarian works" Hubbard has instituted that are "helping to eradicate illiteracy, drug abuse and criminality" in the city. Los Angeles Street Named for Scientologist Founder, DEUTSCHE PRESSE-AGENTUR, Apr. 6, 1997, available in LEXIS, News Library, DPA File. 3. The quoted language is translated from the German "Riesenkrake" and "menschenverachtendes Kartell der Unterdruickung." Entscheidungen des Oberver- waltungsgerichts [OVG] [Administrative Court of Appeals] Minster, 5 B 993/95 (1996), (visited Oct. -

Fianlists NAEJ 2018

11th NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS FINALISTS A. JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR A1a. JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR—Print * Lorraine Ali, Los Angeles Times * Simi Horwitz, Film Journal International and American Theatre * Randy Lewis, Los Angeles Times * Lacey Rose, The Hollywood Reporter * Ramin Setoodeh, Variety A1b. JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR— Broadcast/Online * Madeleine Brand, KCRW * Matt Donnelly, TheWrap * Kacey Montoya, KTLA 5 News * Morris O'Kelly (Mo'Kelly), KFI AM640/iHeartRadio * Tim Teeman, The Daily Beast A2. PHOTO JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR * Phi Ige, KTLA 5 News * Osceola Refetoff, KCET Link Artbound B. CRITIC — any media platform (print, broadcast or online) B1a. Film * Justin Chang, Los Angeles Times * Owen Gleiberman, Variety * Angie Han, Mashable * Simi Horowitz, Film Journal International * Peter Rainer, Christian Science Monitor B1b. TV * Lorraine Ali, Los Angeles Times, “How TV images of migrant children overrode media pundits and changed the immigration debate” * Daniel D'Addario, Variety * Kevin Fallon, The Daily Beast * Daniel Fienberg, The Hollywood Reporter * Caroline Framke, Variety B2. Performing Arts (theater, music, dance) *Robert Hofler, TheWrap *Randy Lewis, Los Angeles Times, “Taylor Swift's talent remains intact on 'Reputation,' her most focused, most cohesive album yet” *David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter *Stereo Williams, The Daily Beast *Chris Willman, Variety, “Concert Review: Paul Simon Aces His Finals in Farewell Tour’s Hollywood Bowl Stop” B3. Books/Art/Design *Alexis Camins, Truthdig *Christopher Knight, Los Angeles Times, “Bellini masterpieces at the Getty make for one of the year's best museum shows” *MG Lord, New York Times Book Review, “The Paradoxes and Glory of Apollo 8” *Carolina Miranda, Los Angeles Times, “Alejandro Inarritu's terrifying crossing” *Shana Nys Dambrot, Flaunt, “Amir H. -

Fall 2013 Movie Tie-Ins

Fall 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS BENA BELL Open........................................................................................................................................................................2 Impact ......................................................................................................................................................................4 The Bank On Yourself Revolution ..........................................................................................................................5 Brain Changer .........................................................................................................................................................6 If You’re in the Driver’s Seat, Why Are You Lost? ................................................................................................8 What Addicts Know ...............................................................................................................................................9 Jazzy Vegetarian Classics ...................................................................................................................................10 Happy Herbivore Light & Fit ................................................................................................................................12 Better Than Vegan ................................................................................................................................................14 The Citizenship Gap .............................................................................................................................................16 -

Lawyer Fall 2016

161882_Cover_TL-25coverfeature.qxp 9/15/16 8:12 PM Page CvrA TULANE UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL TULANE VOL.32–NO. 1 LAWYER FALL 2016 CHARMS CHALLENGES& ALUMNI IRRESISTIBLY PULLED BACK TO NEW ORLEANS ALSO INSIDE BLOGGING PROFESSORS LAW REVIEW CENTENNIAL DIVERSITY ENDOWMENT 161882_Cover_TL-25coverfeature.qxp 9/15/16 8:12 PM Page CvrB THE DOCKET 1 FRONT-PAGE FOOTNOTES 13 2 DEAN MEYER’S MEMO 3 BRIEFS 5 REAL-WORLD APPS Hands-on Learning 7 WORK PRODUCT Faculty Scholarship FOUR FIVE NEW PROFESSORSHIPS AWARDED. FACULTY TEST IDEAS THROUGH BLOGGING. SCHOLARLY WORK SPANS THE GLOBE. 13 CASE IN POINT CHARMS & CHALLENGES Alumni irresistibly pulled back to New Orleans 22 LAWFUL ASSEMBLY Events & Celebrations 27 RAISING THE BAR Donor Support NEW GRADS PROMOTE DIVERSITY. NEW SCHOLARSHIPS IN LITIGATION, BUSINESS, CIVIL LAW. GIFT ENHANCES CHINA INITIATIVES. 39 CLASS ACTIONS Alumni News & Reunions TULANE REMEMBERS JOHN GIFFEN WEINMANN. RIGHT: The 2016-17 LLMs and international students show their Tulane Law pride. Update your contact information at tulane.edu/alumni/update. Find us online: law.tulane.edu facebook.com/TulaneLawSchool Twitter: @TulaneLaw bit.ly/TulaneLawLinkedIn www.youtube.com/c/TulaneLaw FALL 2016 TULANE LAWYER VOL.32–NO.1 161882_01-2_TL-25coverfeature.qxp 9/15/16 7:19 PM Page 1 FRONT-PAGE FOOTNOTES CLASS PORTRAIT TULANE LAW SCHOOL CLASS OF 2019 198 students 100+ colleges/universities represented 34 U.S. jurisdictions represented THE CLASS OF 2019 INCLUDES: A speechwriter for a South American country’s mission at the United Nations age range 20–52 -

The Case Against Celebrity Mark Ebner, Andrew Breitbart

[PDF] Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Mark Ebner, Andrew Breitbart - pdf download free book Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity PDF Download, Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Download PDF, Free Download Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Full Popular Mark Ebner, Andrew Breitbart, Free Download Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Full Version Mark Ebner, Andrew Breitbart, PDF Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Free Download, online free Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity, Download PDF Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Free Online, read online free Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity, Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Mark Ebner, Andrew Breitbart pdf, book pdf Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity, Download pdf Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity, Download Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity E-Books, Read Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity Online Free, Pdf Books Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic In Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity, -

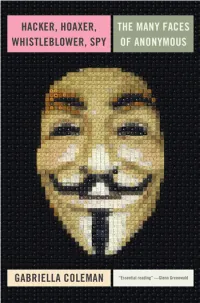

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara a Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz a Diss

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Kathleen Anne Swift Committee in charge: Professor Richard Duran, Chair Professor Diana Arya Professor William Robinson September 2017 The dissertation of Kathleen Anne Swift is approved. ................................................................................................................................ Diana Arya ................................................................................................................................ William Robinson ................................................................................................................................ Richard Duran, Committee Chair June 2017 A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Copyright © 2017 by Kathleen Anne Swift iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their advice and patience as I worked on gathering and analyzing the copious amounts of research necessary to write this dissertation. Ongoing conversations about hacktivism, Anonymous, Swartz, Snowden, and the rise of the surveillance state have been interesting to say the least. I appreciate all the counsel and guidance I have received over the years. In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. -

Bling Ring: a Gangue De Hollywood, Ela Apresenta Todos Os Detalhes De Uma Das Quadrilhas Mais Audaciosas De Nossos Tempos

1 2 Entre 2008 e 2009, as residências de Lindsay Lohan, Orlando Bloom, Paris Hilton e diversas outras celebridades foram invadidas e saqueadas. Os ladrões, um grupo de jovens criados em um endinheirado subúrbio de Los Angeles, levaram o equivalente a 3 milhões de dólares em joias, dinheiro e artigos de grife, como relógios Rolex, bolsas Louis Vuitton, perfumes Chanel e jaquetas Diane von Furstenberg. As notícias surpreendentes sobre o caso chocaram Hollywood e intrigaram o mundo. Por que esses garotos, que em nada correspondiam à tradicional imagem dos bandidos, realizaram crimes tão ousados? A jornalista Nancy Jo Sales entrevistou todos os envolvidos, incluindo os pais e os advogados dos jovens, e até mesmo as celebridades que sofreram os assaltos. Em Bling Ring: a gangue de Hollywood, ela apresenta todos os detalhes de uma das quadrilhas mais audaciosas de nossos tempos. A história real também inspirou o filme de Sofia Coppola, estrelado por Emma Watson. 3 Da esquerda para a direita, no alto: Diana Tamayo, Jonathan Ajar, Alexis Neiers e Rachel Lee; embaixo: Nick Prugo, Courtney Ames e Roy Lopez. 4 PREFÁCIO Na primavera de 2010, recebi um recado de alguém do escritório de Sofia Coppola dizendo que ela estava interessada em comprar os direitos de filmagem da minha reportagem “The Suspects Wore Louboutins” [Os suspeitos usavam Louboutin] para a revista Vanity Fair, que tinha acabado de ser publicada na edição dedicada a Hollywood daquele ano. Fiquei entusiasmada, mas também intrigada em saber por que essa história teria atraído o interesse de Sofia Coppola. Era sobre uma quadrilha formada por adolescentes entre 2008 e 2009 que tinham escolhido como alvo as casas da nova geração de astros de Hollywood. -

Celebrities Keeping Scientology Working Stephen A

5 Celebrities Keeping Scientology Working Stephen A. Kent L. Ron Hubbard was prescient with his realization about the impact that stars and celebrities had upon ordinary people in mass culture. People imitated and emulated them, often modeling aspects of their own lives according to what actors did on stage or how they lived their lives off-camera. Statements that he made about the celebrities in the entertainment industry fostered among some of them an inflated feeling of self-importance, portraying them as art- ists who shaped the development of civilization. The artists who absorbed this inflated view of their contributions did so as they socialized into the subcultural world that Hubbard created, in which they equated civilizational advance with furthering Scientology’s influence. Serving Scientology, there- fore, was a means by which they felt that they were contributing to society’s advancement, and if by doing so, they caught the eye of a producer looking to fill a part in a film, then ever so much the better. This chapter examines the way that Scientology utilizes celebrities in the organization’s overall effort to “keep Scientology working.” I kept in mind the overall description of elites that appears in resource mobilization theory, since these celebrities have the flexible time, resources, and media connec- tions that allows them to open areas nationally or internationally in which they can proselytize. More importantly, however, might be the significance of having celebrity status itself, because that status carries with it forms of unique, valuable assets that its possessors can use to influence others in soci- ety.