Baking Properties and Microstructure of Pseudocereal Xours in Gluten-Free Bread Formulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Seed Times

FODDER AND PSEUDOCEREAL SEED PRODUCTION (STATUS, CONSTRAINT, AND STRATEGIES) Volume 13 No. 2, May - Aug 2020 The National Seed Association of India Magazine FODDER AND PSEUDOCEREAL SEED PRODUCTION (Status, Constraint and Strategies) SEED TIMES 1 May - August 2020 FODDER AND PSEUDOCEREAL SEED PRODUCTION (STATUS, CONSTRAINT, AND STRATEGIES) 2 SEED TIMES May - August 2020 FODDER AND PSEUDOCEREAL SEED PRODUCTION (STATUS, CONSTRAINT, AND STRATEGIES) ABOUT NSAI National Seed Association of India (NSAI) is the apex a wide range of agro-climatic zones. It actively contributes to organization representing the Indian seed industry. The vision the seed industry policy development, with the concerned of NSAI is to create a dynamic, innovative and internationally governments, to ensure that policies and regulations create an competitive, research based industry producing high enabling environment, including public acceptance, so that the performance, high quality seeds and planting materials which industry is globally competitive. benefit farmers and significantly contribute to the sustainable growth of Indian Agriculture. NSAI promotes harmonization and adoption of best commercial practices in production, processing, quality control and The mission of NSAI is to encourage investment in state of distribution of seeds. the art R&D to bring to the Indian farmer superior genetics and technologies, which are high performing and adapted to NSAI Office Bearers NSAI Governing Council Members President: Mr. M. Prabhakar Rao Mr. N.P. Patel Mr. K. Praveen Kumar Nuziveedu Seeds Ltd. Western Agri Seeds Ltd Asian Agri Genetics Ltd. Vice President: Mr. Kamal O. Zunzunwala Mr. Arun Kumar Agarwalla Mr. Siddhartha S Sen Safal Seeds & Biotech Ltd West Bengal Hybrid Seeds Parasmoni Organic & Agri Products Mr. -

Seed Dormancy and Preharvest Sprouting in Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd)

plants Review Seed Dormancy and Preharvest Sprouting in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd) Emma M. McGinty 1, Kevin M. Murphy 2 and Amber L. Hauvermale 2,* 1 The School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, P.O. Box 644236, Pullman, WA 99164, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Crop and Soil Science, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.:+1-509-335-3661 Abstract: Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) is a culturally significant staple food source that has been grown for thousands of years in South America. Due to its natural drought and salinity tolerance, quinoa has emerged as an agronomically important crop for production in marginal soils, in highly variable climates, and as part of diverse crop rotations. Primary areas of quinoa research have focused on improving resistance to abiotic stresses and disease, improving yields, and increasing nutrition. However, an evolving issue impacting quinoa seed end-use quality is preharvest sprouting (PHS), which is when seeds with little to no dormancy experience a rain event prior to harvest and sprout on the panicle. Far less is understood about the mechanisms that regulate quinoa seed dormancy and seed viability. This review will cover topics including seed dormancy, orthodox and unorthodox dormancy programs, desiccation sensitivity, environmental and hormonal mechanisms that regulate seed dormancy, and breeding and non-breeding strategies for enhancing resistance to PHS in quinoa. Citation: McGinty, E.M.; Murphy, Keywords: abscisic acid; desiccation sensitivity; gibberellin; hormone signaling; precocious germina- K.M.; Hauvermale, A.L. Seed tion; seed morphology Dormancy and Preharvest Sprouting in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd). -

Eurostat Handbook for Annual Crop Statistics

Annual crop statistics Handbook 2020 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Changes from previous versions ............................................................................................. 6 1.1.1 Changes in classification .................................................................................................. 6 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Definitions and concepts ........................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Area ...................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2 Production ......................................................................................................................... 13 2.1.3 Humidity degree ............................................................................................................... 13 2.1.4 Yield ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Units of measurement ............................................................................................................ -

The Effects of Cereal Brans, Pseudocereal and Enzymes on The

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. The effects of cereals bran, pseudocereal and enzymes on the Chinese steamed bread dough and bread quality A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Philosophy in Food Science at Lincoln University by Wenjun Liu Lincoln University 2018 Declaration Some parts of this thesis have been published, submitted and/or presented at Conferences in advance of submission of the thesis: Publications ⚫ Liu, W., Brennan, M. A., Serventi, L., & Brennan, C. S. (2017). Effect of cellulase, xylanase and α-amylase combinations on the rheological properties of Chinese steamed bread dough enriched in wheat bran. Food chemistry, 234, 93-102. ⚫ Liu, W., Brennan, M., Serventi, L., & Brennan, C. (2017). Effect of wheat bran on dough rheology and final quality of Chinese steamed bread. Cereal Chemistry, 94(3), 581-587. ⚫ Liu, W., Brennan, M., Serventi, L., & Brennan, C. (2017). Buckwheat flour inclusion in Chinese steamed bread: Potential reduction in glycaemic response and effects on dough quality. European Food Research and Technology, 243(5), 727-734. -

Pseudocereal Grains: Nutritional Value, Health Benefits and Current Applications

Pseudocereal grains: Nutritional value, health benefits and current applications for the development of gluten-free foods Cristina Martínez-Villaluenga 1, Elena Peñas 1, Blanca Hernández-Ledesma 2, * 1 Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition (ICTAN-CSIC), Juan de la Cierva 3, 28006 Madrid, Spain. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias de la Alimentación (CIAL, CSIC-UAM, CEI- UAM+CSIC), Nicolás Cabrera 9, 28049 Madrid, Spain. Email: [email protected] * Corresponding author. B. Hernández-Ledesma Tel.: +34 910017970; fax: +34 910017905. E-mail address: [email protected] Abbreviations: DIAAS, digestible indispensable amino acid scores; dw, dry weight; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GF, gluten free; ICR, Institute of Cancer Research; IGF-1, insulin like growth factor; IL, interleukin; LDL, low density lipoproteins; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO, nitric oxide; PDCAAS, protein digestibility corrected amino acid score; POx, prolin oxidase; PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; RS, resistant starch; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha. 1. Introduction Pseudocereals grains are edible seeds belonging to dicotyledonous species that are known as such due to their similar physical appearance and high starch content similar to true cereals (monocotyledonous of the Poaceae family) (Alvarez-Jubete et al., 2010a). Pseudocereals are promising crops of future due to their high genetic variability that is advantageous for them to be adapted to different environments from tropical to temperate climatic conditions (Joshi et al., 2018 and 2019; Ruiz et al., 2013). The most important species are quinoa ( Chenopodium quinoa Willd), amaranth ( Amaranthus sp.) and buckwheat (Fagopyrum sp.). Quinoa and amaranth belong to Chenopodiaceae family originated from the Andean region in South America. -

Alternative Healthy Food Crops Manju Sharma* and Paul Khurana SM Amity Institute of Biotechnology, Amity University, Haryana, Gurgaon, Manesar-122413, India

ition & F tr oo u d N f S o c Manju and Paul Khurana, J Nutr Food Sci 2014, 4:4 l i e a n n c r e DOI: 10.4172/2155-9600.1000288 u s o J Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences ISSN: 2155-9600 Review Article Open Access Alternative Healthy Food Crops Manju Sharma* and Paul Khurana SM Amity Institute of Biotechnology, Amity University, Haryana, Gurgaon, Manesar-122413, India Abstract Plants having diverse profile in terms of nutrition, availability, tolerance to harsh climatic conditions and possibility of usages as food, forage and biofuel usually referred as Alternative plants. This article will only be focused on the plants having value to reinstate themselves as alternative food crop for the burgeoning population. Indigenous communities across the globe are familiar with a large diversity of flora and fauna that provide sustenance in form of food and medicine. The ‘plants for a future’ website reveals a list of more than 7000 underutilized species with different values (PFAF website). Most of these plants thrive well on impoverished or marginal soils and dry weather conditions. Millets, Buckwheat, Oats, and Chenopods are coming up as imperative nutritious option. The multipurpose use of Millets, Buckwheat, Oats, Chenopods and Barley coupled with early maturity, low nutrient demand and ability to adapt well to marginal and degraded lands makes them an ideal crop for future sustainable agriculture. Keywords: Millets; Chenopods; Oats; Buckwheat; Alternative food; Millets Healthy food Millets are indigenous to many parts of the world; most likely had Introduction an evolutionary origin in tropical western Africa, where they exist in wild and cultivated forms [4]. -

Molecular Advances for Improving Nutrient Bioavailability

REVIEW published: 27 February 2020 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00049 Healthy and Resilient Cereals and Pseudo-Cereals for Marginal Agriculture: Molecular Advances for Improving Nutrient Bioavailability † † Juan Pablo Rodríguez , Hifzur Rahman , Sumitha Thushar and Rakesh K. Singh* Crop Diversification and Genetics Program, International Center for Biosaline Agriculture, Dubai, United Arab Emirates With the ever-increasing world population, an extra 1.5 billion mouths need to be fed by Edited by: 2050 with continuously dwindling arable land. Hence, it is imperative that extra food come Felipe Klein Ricachenevsky, from the marginal lands that are expected to be unsuitable for growing major staple crops Universidade Federal de under the adverse climate change scenario. Crop diversity provides right alternatives for Santa Maria, Brazil marginal environments to improve food, feed, and nutritional security. Well-adapted and Reviewed by: fi Joel B. Mason, climate-resilient crops will be the best t for such a scenario to produce seed and Tufts University School of Medicine, biomass. The minor millets are known for their high nutritional profile and better resilience United States for several abiotic stresses that make them the suitable crops for arid and salt-affected Scott Aleksander Sinclair, Ruhr University soils and poor-quality waters. Finger millet (Eleucine coracana) and foxtail millet (Setaria Bochum, Germany italica), also considered as orphan crops, are highly tolerant grass crop species that grow *Correspondence: well in marginal and degraded lands of Africa and Asia with better nutritional profile. Rakesh K. Singh [email protected]; Another category of grains, called pseudo-cereals, is considered as rich foods because of [email protected] their protein quality and content, high mineral content, and healthy and balance food quality. -

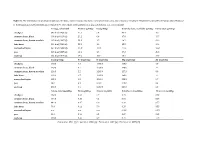

Table S1. the Nutritional Values of Grain Legumes Chickpea, Common

Table S1. The nutritional values of grain legumes chickpea, common bean, faba bean, narrowleaf lupin, pea, and soybean according to Fineli the National Food Composition Database of the Finnish institute for health and welfare [1-6]. The values are expressed on a dry matter basis. n.a., not available Energy, calculated Protein (g/100g) Fat (g/100g) Carbohydrate, available (g/100g) Fiber, total (g/100 g) chickpea 343 kcal (1436 kJ) 21.3 5.4 46.4 10.7 common bean, black 318 kcal (1330 kJ) 21.2 0.9 47.8 15.5 common bean, brown or white 305 kcal (1287 kJ) 22.2 1.5 39.5 21.6 faba bean 331 kcal (1384 kJ) 28.5 1.9 42.2 13.6 narrowleaf lupin 291 kcal (1220 kJ)a 33.8b 13.6b 31.0a 39.9b pea 245 kcal (1025 kJ) 19.4 1.6 27.2 20.0 soybean 374 kcal (1565 kJ) 35.9 17.7 10.3 15.7 Ca (mg/100g) Fe (mg/100g) K (mg/100g) Mg (mg/100g) Zn (mg/100g) chickpea 160.0 5.5 1 000.0 130.0 3.0 common bean, black 160.0 8.7 1 500.0 160.0 2.2 common bean, brown or white 139.5 5.2 1 285.0 157.5 0.0 faba bean 103.0 6.7 1 062.0 192.0 3.1 narrowleaf lupin 152.4c 4.2c 1294.4c 205.5c 3.7c pea 64.0 4.8 918.0 110.0 2.9 soybean 163.0 8.4 1 730.0 225.0 1.0 Folate, total (µg/100g) B6 (mg/100 g) Niacin (mg/100) Riboflavin (mg/100g) Thiamin (mg/100g) chickpea 180.0 0.53 5.2 0.24 0.39 common bean, black 444.0 0.29 6.2 0.19 0.90 common bean, brown or white 441.0 0.47 6.0 0.20 0.55 faba bean 78.8 0.44 7.0 0.35 0.55 narrowleaf lupin n.a. -

From Zero to Hero: the Past, Present and Future of Grain Amaranth Breeding

Theoretical and Applied Genetics https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-018-3138-y REVIEW From zero to hero: the past, present and future of grain amaranth breeding Dinesh C. Joshi1 · Salej Sood2 · Rajashekara Hosahatti1 · Lakshmi Kant1 · A. Pattanayak1 · Anil Kumar3 · Dinesh Yadav4 · Markus G. Stetter5 Received: 26 February 2018 / Accepted: 28 June 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Key message Grain amaranth is an underutilized crop with high nutritional quality from the Americas. Emerging genomic and biotechnological tools are becoming available that allow the integration of novel breeding techniques for rapid improvement of amaranth and other underutilized crops. Abstract Out of thousands of edible plants, only three cereals—maize, wheat and rice—are the major food sources for a majority of people worldwide. While these crops provide high amounts of calories, they are low in protein and other essential nutrients. The dependence on only few crops, with often narrow genetic basis, leads to a high vulnerability of modern crop- ping systems to the predicted climate change and accompanying weather extremes. Broadening our food sources through the integration of so-called orphan crops can help to mitigate the efects of environmental change and improve qualitative food security. Thousands of traditional crops are known, but have received little attention in the last century and breeding eforts were limited. Amaranth is such an underutilized pseudocereal that is of particular interest because of its balanced amino acid and micronutrient profles. Additionally, the C 4 photosynthetic pathway and ability to withstand environmental stress make the crop a suitable choice for future agricultural systems. -

GRAINS: GROWING QUINOA in HOME GARDENS Home Gardens Series

GRAINS: GROWING QUINOA IN HOME GARDENS Home Gardens Series By Julianne A. Kellogg, Sustainable Seed Systems Lab, Dept. of Crop and Soil Sciences, Washington State University. Dr. Kevin M. Murphy, Sustainable Seed Systems Lab, Dept. of Crop and Soil Sciences, Washington State University WSU EXTENSION | GRAINS: GROWING QUINOA IN HOME GARDENS Grains: Growing Quinoa in Home Gardens white, brown, red, and black. Typically prepared in a Crop at a Glance similar manner as boiled rice, quinoa can be served as a grain side dish or incorporated into salads and Growing Season: Spring through late summer or other recipes. Quinoa is desirable not just for its flavor, early fall. described as earthy, nutty, and sweet, but also for its nutritional profile. Quinoa is gluten free, high in Time of Planting: Early spring. protein, and contains all necessary amino acids required Spacing: Sow quinoa seed at a rate of 5–8 g for human health. Many people are now cooking per 100 square feet in rows spaced 8–24 inches this Andean grain at home, and most of the quinoa apart with the option to later thin to 3–5 inches consumed in this country is imported from South between plants. For transplant plugs, plant quinoa America, primarily Bolivia and Peru. This publication is transplants 12 inches apart in rows spaced 12–24 for home gardeners interested in growing quinoa and inches apart. provides information on methods to grow quinoa, how to save seed for future planting, and how to process seed Days to Harvest: 90–150 days, depending on the for consumption. -

Whole Grain Definition

EXPLOITING BIOACTIVITY OF EUROPEAN CEREAL GRAINS FOR IMPROVED NUTRITION AND HEALTH BENEFITS Whole grain definition Introduction The term ‘grain’ applies to the genera and species of the grass family (Poaceae) and includes the pseudocereals and other cereal grains, as set out in Table 1. Pulses, nuts and seeds are not included. All the grains of the Poaceae family are related both structurally and biochemically. Typical grains are energy dense and can vary in starch content (typically 50–80%), depending on the species, origin and environmental growing conditions. Cereal grains are those that are typically included in the bread and cereal groups in dietary guidance in most countries. This whole grain definition is expected to be useful in the context of nutrition recommendations and guidelines and nutrition claims. Health claims, on the other hand, must be based on documentation of specific effects of grains or grain components in the diet. Table 1. Whole grain sources Cereal Scientific name Cereals Wheat, including spelt, emmer, faro, Triticum spp. einkorn, khorasan wheat1, durum Rice, including brown, black, red and other Oryza spp. colored rice varieties Barley including hull-less or naked Hordeum spp. barley but not pearled Maize (corn) Zea mays Rye Secale spp. Oats, including hull-less or naked oats Avena spp. Millets Brachiaria spp.; Pennisetum spp.; Panicum spp.; Setaria spp.; Paspalum spp.; Eleusine spp.; Echinochloa spp. Sorghum Sorghum spp. Teff (tef) Eragrostis spp. Triticale Triticale 2 Canary seed Phalaris canariensis Job’s tears Coix lacryma-jobi Fonio, black fonio, Asian millet Digitaria spp. Pseudocereals Amaranth Amaranthus caudatus Buckwheat, Tartar buckwheat Fagopyrum spp. -

Chemically Leavened Gluten Free Sorghum Bread by Pervin Ari Akin

Chemically leavened gluten free sorghum bread by Pervin Ari Akin B.S., Celal Bayar University, 2011 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Grain Science and Industry College of Agriculture KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Approved by: Major Professor Rebecca Ann Miller Copyright © Pervin Ari Akin 2017. Abstract Sorghum is unique in terms of its resistance to drought and heat and is grown and consumed around the globe. Moreover, sorghum does not contain gluten and has potential in the gluten-free market. A blend of non-wheat flour, starch and hydrocolloid typically provide the structure of gluten-free products. Most research on sorghum bread uses a yeast leavened process, HPMC gum, rice flour and corn, potato, or tapioca starch. Little is known about the functionality or interactions of different starches and hydrocolloids in sorghum batter. The objectives of this study were to examine starch-hydrocolloid interaction in chemically leavened gluten free sorghum bread; to evaluate the effects of different ingredients on gluten free bread quality made with sorghum flour: starch (tapioca starch, rice flour and potato starch): hydrocolloid (HPMC, locust bean gum and xanthan) and to develop a chemically leavened gluten free sorghum bread method. Bread was baked as pup loaves. Volume index was measured using the AACCI Method 10-91.01 template, crumb grain was evaluated using the C-Cell Imaging System and texture was determined with the TA.XT Plus Texture Analyzer. The base formula was commercial sorghum flour, water, starch, hydrocolloid, sugar, salt, shortening and double acting baking powder.