The Rock Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

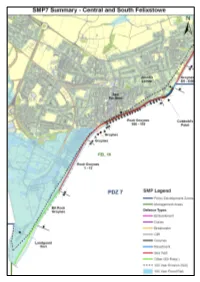

Felixstowe Central and South

Management Responsibilities SCDC: Fel 19.1 to Fel 19.3 SCDC Assets: Fel 19.1 Reinforced concrete block revetment with groynes, rock armour revetment in front of concrete wall, two fishtail breakwaters Fel 19.2 Concrete seawall with rock groynes, concrete splash wall, mass concrete seawall with promenade, timber groynes with concrete cladding Fel 19.3 Mass concrete sea wall with promenade, timber groynes with concrete cladding EA: Fel 19.4 to Fel 20.1 (with flood wall responsibility in SCDC frontages) EA Assets: Fel 19.2 / 19.3 Secondary flood wall Fel 19.4 Manor Terrace sea wall, concrete block-work revetment with toe piling, Landguard Common sea wall with concrete apron SMP Information Area vulnerable to flood risk: Approx. 7,017,000m² No. of properties vulnerable to flooding: 1071 Area vulnerable to erosion: Approx. 640,000m² (2105 prediction – no defences) No. of properties vulnerable to erosion: 111 Vulnerable infrastructure / assets: Felixstowe Leisure Centre, Bartlet Hospital, Felixstowe Docks, Martello Tower, Landguard caravan park, Harwich Harbour Ferry, Landguard Common, Landguard Fort, Orwell Estuary, Stour Estuary SMP Objectives To improve Felixstowe as a viable commercial centre and tourist destination in a sustainable manner; To protect the port of Felixstowe and provide opportunities for its development; To develop and maintain the Blue Flag beach; To maintain flood protection to residential properties; To maintain a high standard of ongoing defence to the area; To maintain existing facilities essential in supporting ongoing regeneration; To integrate maintenance of coastal defence, while promoting sustainable development of the hinterland; To maintain the historical heritage of the frontage; To maintain biological and geological features of Landguard Common SSSI in a favourable condition. -

URBAN COASTAL FLOOD MITIGATION STRATEGIES for the CITY of HOBOKEN & JERSEY CITY, NEW JERSEY by Eleni Athanasopoulou

©[2017] Eleni Athanasopoulou ALL RIGHTS RESERVED URBAN COASTAL FLOOD MITIGATION STRATEGIES FOR THE CITY OF HOBOKEN & JERSEY CITY, NEW JERSEY By Eleni Athanasopoulou A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School- New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Civil and Environmental Engineering Written under the direction of Dr. Qizhong Guo And approved by New Jersey, New Brunswick January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION URBAN COASTAL FLOOD MITIGATION STRATEGIES FOR THE CITY OF HOBOKEN & JERSEY CITY, NEW JERSEY by ELENI ATHANASOPOULOU Dissertation Director: Dr. Qizhong Guo Coastal cities are undeniably vulnerable to climate change. Coastal storms combining with sea level rise have increased the risk of flooding and storm surge damage in coastal communities. The communities of the City of Hoboken and Jersey City are low-lying areas along the Hudson River waterfront and the Newark Bay/Hackensack River with little or no relief. Flooding in these areas is a result of intense precipitation and runoff, tides and/or storm surges, or a combination of all of them. During Super-storm Sandy these communities experienced severe flooding and flood-related damage as a result of the storm surge. ii Following the damage that was created on these communities by flooding from Sandy, this research was initiated in order to develop comprehensive strategies to make Hoboken and Jersey City more resilient to flooding. Commonly used flood measures like storage, surge barrier, conveyance, diversion, pumping, rainfall interception, etc. are examined, and the research is focused on their different combination to address different levels of flood risk at different scales. -

On the Reflectance of Uniform Slopes for Normally Incident Interfacial Solitary Waves

1156 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 37 On the Reflectance of Uniform Slopes for Normally Incident Interfacial Solitary Waves DANIEL BOURGAULT Department of Physics and Physical Oceanography, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada DANIEL E. KELLEY Department of Oceanography, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada (Manuscript received 29 March 2005, in final form 2 September 2006) ABSTRACT The collision of interfacial solitary waves with sloping boundaries may provide an important energy source for mixing in coastal waters. Collision energetics have been studied in the laboratory for the idealized case of normal incidence upon uniform slopes. Before these results can be recast into an ocean parameter- ization, contradictory laboratory findings must be addressed, as must the possibility of a bias owing to laboratory sidewall effects. As a first step, the authors have revisited the laboratory results in the context of numerical simulations performed with a nonhydrostatic laterally averaged model. It is shown that the simulations and the laboratory measurements match closely, but only for simulations that incorporate sidewall friction. More laboratory measurements are called for, but in the meantime the numerical simu- lations done without sidewall friction suggest a tentative parameterization of the reflectance of interfacial solitary waves upon impact with uniform slopes. 1. Introduction experiments addressed the idealized case of normally incident ISWs on uniform shoaling slopes in an other- Diverse observational case studies suggest that the wise motionless fluid with two-layer stratification. The breaking of high-frequency interfacial solitary waves results of these experiments showed that the fraction of (ISWs) on sloping boundaries may be an important ISW energy that gets reflected back to the source after generator of vertical mixing in coastal waters (e.g., impinging the sloping boundary depends on the ratio of MacIntyre et al. -

Swash Zone Based Reflection During Energetic Wave Conditions at a Dissipative Beach: Toward a Wave-By-Wave Approach

SWASH ZONE BASED REFLECTION DURING ENERGETIC WAVE CONDITIONS AT A DISSIPATIVE BEACH: TOWARD A WAVE-BY-WAVE APPROACH Rafael Almar1, Patricio Catalán2, Raimundo Ibaceta2, Chris Blenkinsopp3, Rodrigo Cienfuegos4, Mauricio Villagrán4,5, Juan Carlos Aguilera4 and Bruno Castelle6 This paper presents a 11-day experiment conducted at the high-energy dissipative beach of Mataquito, Maule Region, Chile. During the experiment, offshore significant wave height ranged 1-4 m, with persistent long period up to 18 s and oblique incidence. Wave energy reflection value ranged from 1 to 4 %, and results show that it is highly linked to both incoming wave characteristics and swash zone beach slope, and is well correlated to a swash-slope based Iribarren number. The swash acting as a low-pass filter in the reflection mechanism, our results show that the cut-off period is better determined by swash slope rather than incoming wave's period. A new low cost technique for observing high-frequency swash hydro-morphodynamics is introduced and validated using LIDAR measurements. A good agreement is found. Separation of uprush and backswash components using the Radon Transform illustrates the low-frequency filtering effect. These results show the key role played by swash mechanism in the reflection rate and frequency selection. More investigation is needed to describe the reflection process and its link with shoreface evolution, moving toward a swash-by-swash approach. Keywords: Mataquito, Maule Region, Chile; beach reflection; incoming and outgoing wave separation; swash measurements technique; video; Lidar INTRODUCTION There is a potential for substantial wave reflection at the coast, depending on hydro- and morphodynamic conditions. -

Chapter 216 Extreme Water Levels, Wave Runup And

CHAPTER 216 EXTREME WATER LEVELS, WAVE RUNUP AND COASTAL EROSION P. Ruggiero1 , P.D. Komar2, W.G. McDougal1 and R.A. Beach2 ABSTRACT A probabilistic model has been developed to analyze the susceptibilities of coastal properties to wave attack. Using an empirical model for wave runup, long term data of measured tides and waves are combined with beach morphology characteristics to determine the frequency of occurrence of sea cliff and dune erosion along the Oregon coast. Extreme runup statistics have been characterized for the high energy dissipative conditions common in Oregon, and have been found to depend simply on the deep-water significant wave height. Utilizing this relationship, an extreme-value probability distribution has been constructed for a 15 year total water elevation time series, and recurrence intervals of potential erosion events are calculated. The model has been applied to several sites along the Oregon coast, and the results compare well with observations of erosional impacts. INTRODUCTION Much of the Oregon coast is characterized by wide, dissipative, sandy beaches, which are backed by either large sea cliffs or sand dunes. This dynamic coast typically experiences a very intense winter wave climate, and there have been many documented cases of dramatic, yet episodic, sea cliff and dune erosion (Komar and Shih, 1993). A typical response of property owners following such erosion events is to build large coastal protection structures. Often these structures are built after a single erosion event, which is followed by a long period with no significant wave attack. From a coastal management perspective, it is of interest to be able to predict the expected frequency and intensity of such erosion events to determine if a coastal structure is an appropriate response. -

Α Ρ Α Ρ Ρ Ρ Cot Cot 1 K H K H M ∆ = ⌋ ⌉

ARMOR POROSITY AND HYDRAULIC STABILITY OF MOUND BREAKWATERS Josep R. Medina1, Vicente Pardo2, Jorge Molines1, and M. Esther Gómez-Martín3 Armor porosity significantly affects construction costs and hydraulic stability of mound breakwaters; however, most hydraulic stability formulas do not include armor porosity or packing density as an explicative variable. 2D hydraulic stability tests of conventional randomly-placed double-layer cube armors with different armor porosities are analyzed. The stability number showed a significant 1.2-power relationship with the packing density, similar to what has been found in the literature for other armor units; thus, the higher the porosity, the lower the hydraulic stability. To avoid uncontrolled model effects, the packing density should be routinely measured and reported in small-scale tests and monitored at prototype scale. Keywords: mound breakwater; armor porosity; packing density; armor damage; armor unit; cubic block. INTRODUCTION When quarries are not able to provide stones of the adequate size and price, precast concrete armor units (CAUs) are required for the armor layer protecting large mound breakwaters. The first CAUs, introduced in the 19th century, were massive cubes and parallelepiped blocks with a very simple geometry. Since the invention of the Tetrapod in 1950, numerous precast CAUs with complex geometries have been invented to reduce the cost and to improve the armor layer performance. The overall breakwater construction cost depends on a variety of design and logistic factors, like armor material (reinforced concrete, quality of unreinforced concrete, granite rock, sandstone rock, etc.), armor unit geometry (cube, Tetrapod, etc.), armor unit mass (3, 10, 40, 150-tonne, etc.), casting, handling and stacking equipment, transportation and placement equipment, energy, materials and personnel costs. -

Feasibility Study of an Artifical Sandy Beach at Batumi, Georgia

FEASIBILITY STUDY OF AN ARTIFICAL SANDY BEACH AT BATUMI, GEORGIA ARCADIS/TU DELFT : MSc Report FEASIBILITY STUDY OF AN ARTIFICAL SANDY BEACH AT BATUMI, GEORGIA Date May 2012 Graduate C. Pepping Educational Institution Delft University of Technology, Faculty Civil Engineering & Geosciences Section Hydraulic Engineering, Chair of Coastal Engineering MSc Thesis committee Prof. dr. ir. M.J.F. Stive Delft University of Technology Dr. ir. M. Zijlema Delft University of Technology Ir. J. van Overeem Delft University of Technology Ir. M.C. Onderwater ARCADIS Nederland BV Company ARCADIS Nederland BV, Division Water PREFACE Preface This Master thesis is the final part of the Master program Hydraulic Engineering of the chair Coastal Engineering at the faculty Civil Engineering & Geosciences of the Delft University of Technology. This research is done in cooperation with ARCADIS Nederland BV. The report represents the work done from July 2011 until May 2012. I would like to thank Jan van Overeem and Martijn Onderwater for the opportunity to perform this research at ARCADIS and the opportunity to graduate on such an interesting subject with many different aspects. I would also like to thank Robbin van Santen for all his help and assistance for the XBeach model. Furthermore I owe a special thanks to my graduation committee for the valuable input and feedback: Prof. dr. ir. M.J.F. Stive (Delft University of Technology) for his support and interest in my graduation work; Dr. ir. M. Zijlema (Delft University of Technology) for his support and reviewing the report; ir. J. van Overeem (Delft University of Technology ) for his supervisions, useful feedback and help, support and for reviewing the report; and ir. -

Dot 23231 DS1.Pdf

US DOT FHWA SUMMARY PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. NM08MNT-01 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Data STANDARDS FOR TIRE-BALE EROSION CONTROL AND BANK STABILIZATION PROJECTS: VALIDATION OF 6. Performing Organization Code EXISTING PRACTICE AND IMPLEMENTATION 7. Authors(s): Ashok Kumar Ghosh; Claudia M. Dias Wilson; Andrew Budek- 8. Performing Organization Report No. Schmeisser; Mehrdad Razavi; Bruce Harrision; Naitram Birbahadur; Prosfer Felli, and Barbara Budek-Schmeisser 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology 801 Leroy Place 11. Contract or Grant No. Socorro, N.M. 87801 CO5119 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address NMDOT Research Bureau Final Report 7500B Pan American Freeway March 2008 – September 2010 PO Box 94690 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Albuquerque, NM 87199-4690 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract In an effort to promote the use of increasing stockpiles of waste tires and a growing demand for adequate backfill material in highway construction, NMDOT has embarked on a move to use compressed tire-bales as a means to reduce cost of construction and to recycle used tires which would otherwise occupy much larger space in landfills or be improperly disposed. Compressing the tires into bales has prompted unique environmental, technical, and economic opportunities. This is due to the significant volume reduction obtained when using tire-bales (approximately 100 auto tires with a volume of 20 cubic yards can be compressed to 2 cubic yard blocks, i.e. a tenfold reduction in landfill space). -

Capability Statement Coastal Engineering Delta Marine Consultants Delta Marine Consultants

Capability Statement Coastal Engineering Delta Marine Consultants Delta Marine Consultants Delta Marine Consultants (DMC) was founded in 1978 for the purpose of providing consultancy, project management and engineering design services to clients on a worldwide basis. The company has expertise in the fields of urban infrastructure, large-scale transport infrastructure, ports and harbour development and coastal engineering. The company holds strong links with the construction industry through its parent company, the Royal BAM Group. This contributes to the ability to provide solutions to practical problems and to blend innovation with reliability in design. DMC has been rebranded into ‘BAM Infraconsult’ and is working under that name in the home market. DMC is still used as a trade name for international projects and referred to as such in this Design Capability Statement. DMC has well over 300 employees working in various offices worldwide. The head office is in Gouda (the Netherlands) and apart from several other offices in the Netherlands, local offices are also located in Singapore, Dubai, Jakarta and Perth. DMC is or has been active in a great number of other countries on project basis, often together with BAM contracting companies. Our Core Business Coastal engineering, is one of the core expertise areas of DMC. The interaction between land and water creates complex environments. Coastal areas and river banks have always been important to trade and are therefore vital links in the economic chain. Coastal works, just like ports, are very much influenced by natural phenomena such as tidal change, wave action and extreme weather conditions, which is why they call for specialized expertise. -

Coastal and Ocean Engineering

May 18, 2020 Coastal and Ocean Engineering John Fenton Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources Management Vienna University of Technology, Karlsplatz 13/222, 1040 Vienna, Austria URL: http://johndfenton.com/ URL: mailto:[email protected] Abstract This course introduces maritime engineering, encompassing coastal and ocean engineering. It con- centrates on providing an understanding of the many processes at work when the tides, storms and waves interact with the natural and human environments. The course will be a mixture of descrip- tion and theory – it is hoped that by understanding the theory that the practicewillbemadeallthe easier. There is nothing quite so practical as a good theory. Table of Contents References ....................... 2 1. Introduction ..................... 6 1.1 Physical properties of seawater ............. 6 2. Introduction to Oceanography ............... 7 2.1 Ocean currents .................. 7 2.2 El Niño, La Niña, and the Southern Oscillation ........10 2.3 Indian Ocean Dipole ................12 2.4 Continental shelf flow ................13 3. Tides .......................15 3.1 Introduction ...................15 3.2 Tide generating forces and equilibrium theory ........15 3.3 Dynamic model of tides ...............17 3.4 Harmonic analysis and prediction of tides ..........19 4. Surface gravity waves ..................21 4.1 The equations of fluid mechanics ............21 4.2 Boundary conditions ................28 4.3 The general problem of wave motion ...........29 4.4 Linear wave theory .................30 4.5 Shoaling, refraction and breaking ............44 4.6 Diffraction ...................50 4.7 Nonlinear wave theories ...............51 1 Coastal and Ocean Engineering John Fenton 5. The calculation of forces on ocean structures ...........54 5.1 Structural element much smaller than wavelength – drag and inertia forces .....................54 5.2 Structural element comparable with wavelength – diffraction forces ..56 6. -

Chapter 103 the Core-Loc: Optimized Concrete Armor

CHAPTER 103 THE CORE-LOC: OPTIMIZED CONCRETE ARMOR Jeffrey A. Melby, A.M. ASCE and George F. Turk1 ABSTRACT: This paper outlines the development and initial testing of a new optimized armor shape, called CORE-LOC, that balances and optimizes engineering performance features such as hydraulic stability, strength, and layer porosity. The new shape has significantly reduced design stresses over many existing shapes, yet has superior interlocking and therefore greater stability. The unit has internal maximum tensile stress levels of approximately half that of dolosse and, therefore, should not need reinforcement. For over 1000 flume tests, the core-loc has demonstrated two-dimensional no-damage stability numbers over 7 and Hudson stability coefficients over 250. In nearly all tests, the core-loc layer could not be damaged up to the wave height-period capacities of the flumes. A site-specific three-dimensional stability test of the proposed Noyo, California, offshore breakwater showed a stable no-damage stability number of 2.7 for Hs or a Hudson stability coefficient of 13 when the core-loc armor layer was exposed to repeated attack of a very severe design-level storm. The unit has been designed to be used alone or as a repair unit for dolosse. Core-loc-repaired dolos model slopes showed improved stability over the original dolos slopes. Finally, through reduced volumes, the core-loc layer is substantially more economical than all other commonly-used randomly-placed armor. INTRODUCTION The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USAE) maintains over 1500 rubble 1) Research Hydraulic Engineers, Coastal Engineering Research Center, USAE Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, MS, 39180 1426 CORE-LOC 1427 structures, 17 of which are protected by concrete armor units. -

The Contribution of Wind-Generated Waves to Coastal Sea-Level Changes

1 Surveys in Geophysics Archimer November 2011, Volume 40, Issue 6, Pages 1563-1601 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-019-09557-5 https://archimer.ifremer.fr https://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00509/62046/ The Contribution of Wind-Generated Waves to Coastal Sea-Level Changes Dodet Guillaume 1, *, Melet Angélique 2, Ardhuin Fabrice 6, Bertin Xavier 3, Idier Déborah 4, Almar Rafael 5 1 UMR 6253 LOPSCNRS-Ifremer-IRD-Univiversity of Brest BrestPlouzané, France 2 Mercator OceanRamonville Saint Agne, France 3 UMR 7266 LIENSs, CNRS - La Rochelle UniversityLa Rochelle, France 4 BRGMOrléans Cédex, France 5 UMR 5566 LEGOSToulouse Cédex 9, France *Corresponding author : Guillaume Dodet, email address : [email protected] Abstract : Surface gravity waves generated by winds are ubiquitous on our oceans and play a primordial role in the dynamics of the ocean–land–atmosphere interfaces. In particular, wind-generated waves cause fluctuations of the sea level at the coast over timescales from a few seconds (individual wave runup) to a few hours (wave-induced setup). These wave-induced processes are of major importance for coastal management as they add up to tides and atmospheric surges during storm events and enhance coastal flooding and erosion. Changes in the atmospheric circulation associated with natural climate cycles or caused by increasing greenhouse gas emissions affect the wave conditions worldwide, which may drive significant changes in the wave-induced coastal hydrodynamics. Since sea-level rise represents a major challenge for sustainable coastal management, particularly in low-lying coastal areas and/or along densely urbanized coastlines, understanding the contribution of wind-generated waves to the long-term budget of coastal sea-level changes is therefore of major importance.