Reading the Borderlands in the Fiction of Zoë Wicomb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Annual Report

eMedia Holdings | 2020 INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL eMedia Holdings | 2020 INTEGRATED 2020 INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS 2 Group at a glance 3 About this report 4 Who we are 19 5 Our companies 6 Financial highlights Corporate governance 8 Directors’ profile 20 Corporate governance report 10 Chief executive officer’s report 24 King lV application register 14 Operations report 29 Report of the audit and risk committee 15 Shareholder snapshot 31 Report of the remuneration committee 18 Directors’ interest in shares 33 Report of the social and ethics committee 34 Sustainability report 34 Environmental 36 Transformation 38 Human relations 39 Summarised annual financial results 40 Directors’ report 44 Declaration by the company secretary 45 Independent auditor’s report 46 Summarised consolidated financial results 52 Notes to the summarised consolidated results 59 Notice of annual general meeting 67 Form of proxy 68 Notes to form of proxy 69 Corporate information eMedia Holdings integrated annual report 2020 1 GROUP AT A GLANCE Ethical conduct, good corporate governance and risk governance are fundamental to the way that eMedia Holdings manages its business. Stakeholders’ interests are balanced against effective risk management and eMedia Holdings’ obligations to ensure ethical management and responsible control. 2 eMedia Holdings integrated annual report 2020 ABOUT THIS REPORT eMedia Holdings Limited (eMedia Holdings) presents this for the approval of these, which are then endorsed by the integrated annual report for the year ended 31 March 2020. board. All risks that are considered material to the business have This report aims to provide stakeholders with a comprehensive been included in this report. -

Blurred Lines

BLURRED LINES: HOW SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM HAS CHANGED WITH A NEW DEMOCRACY AND EVOLVING COMMUNICATION TOOLS Zoe Schaver The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism Advised by: __________________________ Chris Roush __________________________ Paul O’Connor __________________________ Jock Lauterer BLURRED LINES 1 ABSTRACT South Africa’s developing democracy, along with globalization and advances in technology, have created a confusing and chaotic environment for the country’s journalists. This research paper provides an overview of the history of the South African press, particularly the “alternative” press, since the early 1900s until 1994, when democracy came to South Africa. Through an in-depth analysis of the African National Congress’s relationship with the press, the commercialization of the press and new developments in technology and news accessibility over the past two decades, the paper goes on to argue that while journalists have been distracted by heated debates within the media and the government about press freedom, and while South African media companies have aggressively cut costs and focused on urban areas, the South African press has lost touch with ordinary South Africans — especially historically disadvantaged South Africans, who are still struggling and who most need representation in news coverage. BLURRED LINES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction A. Background and Purpose B. Research Questions and Methodology C. Definitions Chapter II: Review of Literature A. History of the Alternative Press in South Africa B. Censorship of the Alternative Press under Apartheid Chapter III: Media-State Relations Post-1994 Chapter IV: Profits, the Press, and the Public Chapter V: Discussion and Conclusion BLURRED LINES 3 CHAPTER I: Introduction A. -

South Africa

South Africa South Africa has a long history. Since a lot of human beings look at my words, I have decided to write on this issue since the recent events going on in the country of South Africa. Its history begins with black human beings as the first human beings on Earth in the great continent of Africa are black. It is found in the southern tip of Africa. It has been in the international news a lot lately. Many viewers here are from South Africa, so I decided to write about South Africa. It has over 51 million human beings living there. Its population is mostly black African in about 80% of its population, but it is still highly multiethnic. Eleven languages are recognized in the South African constitution. All ethnic and language groups have political representation in the country's constitutional democracy. It is made up of a parliamentary republic . Unlike most Parliamentary Republics, the positions of head of State and head of government are merged in a parliament-dependent President. South Africa has the largest communities of European, Asian, and racially mixed ancestry in Africa. The World Bank calls South Africa as an upper middle income economy. It has the largest economy in Africa. South Africa has been through a lot of issues in the world. Also, South Africa can make a much better future. Apartheid is gone, which is a good thing. It is good to not see reactionary mobs and the police to not massively kill university students in Soweto. It is good to not allow certain papers dictate your total travels. -

Download/Pdf/39666742.Pdf De Vries, Fred (2006)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Restless collection: Ivan Vladislavić and South African literary culture Katie Reid PhD Colonial and Postcolonial Cultures University of Sussex January 2017 For my parents. 1 Acknowledgments With thanks to my supervisor, Professor Stephanie Newell, who inspired and enabled me to begin, and whose drive and energy, and always creative generosity enlivened the process throughout. My thanks are due to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding the research. Thanks also to the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas in Austin, for a Dissertation Fellowship (2011-12); and to the School of English at the University of Sussex for grants and financial support to pursue the research and related projects and events throughout, and without which the project would not have taken its shape. I am grateful to all staff at the research institutions I have visited: with particular mention to Gabriela Redwine at the HRC; everyone at the National English Literary Museum, Grahamstown; and all those at Pan McMillan, South Africa, who provided access to the Ravan Press archives. -

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd Is Assassinated in the House of Assembly by a Parliamentary Messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd is assassinated in the House of Assembly by a parliamentary messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September. Balthazar J Vorster becomes Prime Minister on 13 September. 1967 The Terrorism Act is passed, in terms of which police are empowered to detain in solitary confinement for indefinite periods with no access to visitors. The public is not entitled to information relating to the identity and number of people detained. The Act is allegedly passed to deal with SWA/Namibian opposition and NP politicians assure Parliament it is not intended for local use. Besides being used to detain Toivo ya Toivo and other members of Ovambo People’s Organisation, the Act is used to detain South Africans. SAP counter-insurgency training begins (followed by similar SADF training in the following year). Compulsory military service for all white male youths is extended and all ex-servicemen become eligible for recall over a twenty-year period. Formation of the PAC armed wing, the Azanian Peoples Liberation Army (APLA). MK guerrillas conduct their first military actions with ZIPRA in north-western Rhodesia in campaigns known as Wankie and Sepolilo. In response, SAP units are deployed in Rhodesia. 1968 The Prohibition of Political Interference Act prohibits the formation and foreign financing of non-racial political parties. The Bureau of State Security (BOSS) is formed. BOSS operates independently of the police and is accountable to the Prime Minister. The PAC military wing attempts to reach South Africa through Botswana and Mozambique in what becomes known as the Villa Peri campaign. 1969 The ANC holds its first Consultative (Morogoro) Conference in Tanzania, and adopts the ‘Strategies and Tactics of the ANC’ programme, which includes its new approach to the ‘armed struggle’ and ‘political mobilisation’. -

Integrated Annual Report 2019 2019 INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT Worldreginfo - Fe9ca6a0-3330-442E-A99f-Ebe086198619 Website At

Remgro Limited | Integrated Annual Report 2019 2019 INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT WorldReginfo - fe9ca6a0-3330-442e-a99f-ebe086198619 CREATING SHAREHOLDER VALUE SINCE 1948 Originally established in the 1940s by the late Dr Anton Rupert, Remgro’s investment portfolio has evolved substantially and currently includes more than 30 investee companies. MORE INFORMATION This Integrated Annual Report is published as part of a set of reports in respect of the financial year ended 30 June 2019, all of which are available on the Company’s website at www.remgro.com. INVESTOR TOOLS Cross-reference to relevant sections within this report Download from our website: www.remgro.com View more information on our website: www.remgro.com WorldReginfo - fe9ca6a0-3330-442e-a99f-ebe086198619 CONTENTS www.remgro.com | Remgro Limited | Integrated Annual Report 2019 1 OVERVIEW 1OF BUSINESS 4 REMGRO’S APPROACH TO REPORTING 7 SALIENT FEATURES 8 GROUP PROFILE REPORTS TO 10 COMPANY HISTORY SHAREHOLDERS 12 OUR BUSINESS MODEL 2 24 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 14 UNDERSTANDING THE BUSINESS OF AN INVESTMENT HOLDING COMPANY 25 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT 16 KEY OBJECTIVES AND 32 CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER’S REPORT PRINCIPAL INTEGRATED RISKS 40 INVESTMENT REVIEWS 18 DIRECTORATE AND MEMBERS OF COMMITTEES 20 EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE 21 SHAREHOLDERS’ DIARY AND COMPANY INFORMATION FINANCIAL 4 REPORT 118 AUDIT AND RISK COMMITTEE REPORT GOVERNANCE AND 121 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS SUSTAINABILITY 126 REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT AUDITOR 3 127 SUMMARY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 66 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 79 RISK AND OPPORTUNITIES MANAGEMENT REPORT 86 REMUNERATION REPORT 104 SOCIAL AND ETHICS COMMITTEE REPORT 106 ABRIDGED SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT ADDITIONAL 5 INFORMATION 146 FIVE-YEAR REVIEW AND SHARE STATISTICS 148 SHAREHOLDERS’ INFORMATION 151 NOTICE TO SHAREHOLDERS ATTACHED FORM OF PROXY WorldReginfo - fe9ca6a0-3330-442e-a99f-ebe086198619 Remgro invests in businesses that can deliver superior earnings, cash flow generation and dividends over the long term. -

Betrayal of the Promise: How South Africa Is Being Stolen

BETRAYAL OF THE PROMISE: HOW SOUTH AFRICA IS BEING STOLEN May 2017 State Capacity Research Project Convenor: Mark Swilling Authors Professor Haroon Bhorat (Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town), Dr. Mbongiseni Buthelezi (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand), Professor Ivor Chipkin (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand), Sikhulekile Duma (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University), Lumkile Mondi (Department of Economics, University of the Witwatersrand), Dr. Camaren Peter (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University), Professor Mzukisi Qobo (member of South African research Chair programme on African Diplomacy and Foreign Policy, University of Johannesburg), Professor Mark Swilling (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University), Hannah Friedenstein (independent journalist - pseudonym) Preface The State Capacity Research Project is an interdisciplinary, inter- that the individual confidential testimonies they were receiving from university research partnership that aims to contribute to the Church members matched and confirmed the arguments developed public debate about ‘state capture’ in South Africa. This issue has by the SCRP using largely publicly available information. This dominated public debate about the future of democratic governance triangulation of different bodies of evidence is of great significance. in South Africa ever since then Public Protector Thuli Madonsela published her report entitled State of Capture in late 2016.1 The The State Capacity Research Project is an academic research report officially documented the way in which President Zuma and partnership between leading researchers from four Universities senior government officials have colluded with a shadow network of and their respective research teams: Prof. Haroon Bhorat from the corrupt brokers. -

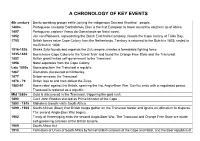

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire. -

Case Number: 14/2019

CASE NUMBER: 14/2019 DATE OF HEARING: 8 AUGUST 2019 JUDGMENT RELEASE DATE: 23 AUGUST 2019 eNCA APPELLANT vs STRYDOM AND TAYLOR RESPONDENT APPEAL TRIBUNAL: MR BRIAN MAKEKETA (DEPUTY CHAIRPERSON) MR TSHIDI SEANE MS NOKUBONGA FAKUDE FOR THE APPELLANT: Mr Ndivhuho Norman Munzhelele, General Head: Regulatory and Strategy accompanied by Mr Morapedi Pilane, assistant Compliance Officer FOR THE RESPONDENT: Adv Mark Oppenheimer instructed by Hurter Spies Attorneys accompanied by Mr Daniël Eloff: Attorney, Hurter Spies Attorneys and Mr Joost Strydom _____________________________________________________________________________________ The finding under adjudication No: 20A/2019 is confirmed. The appeal is not upheld. eNCA vs Strydom and Taylor, Case No: 14/2019 (BCCSA) _____________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY The Appellant was granted leave to appeal against the finding of the Commissioner under 1 adjudication number 20A/2019. The initial complaint was based on a news broadcast that was aired on the 17th of April 2019 at 19:30. The broadcast consisted of an interview between the Appellant and the Respondent where the Respondent was asked to address some concerns regarding alleged racism. There were allegedly perceptions that the Respondent is racist and that the Respondent’s unique communal structure, where only Afrikaner people or those who identify themselves as Afrikaner can live. The interview was colloquial, and the Respondent appeared to have been able to put forward its version. The dispute however arose when the news reader, after the interview, made remarks where he insisted that the Respondent is racist, and that Black people are only allowed in the Afrikaner community as domestics. After considering all submissions from the Appellant and the Respondent, the Appeal Tribunal has found that the Commissioner was justified in her findings and the Appeal is not upheld. -

Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for White South African Christians

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 10 Original Research Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for white South African Christians Author: A significant factor undermining real racial reconciliation in post-1994 South Africa is 1 Wilhelm J. Verwoerd widespread resistance to shared historical responsibility amongst South Africans racialised as Affiliation: white. In response to the need for localised ‘white work’ (raising self-critical, intragroup 1Studies in Historical Trauma historical awareness for the sake of deepened racial reconciliation), this article aims to Stellenbosch University, contribute to the uprooting of white denialism, specifically amongst Afrikaans-speaking Stellenbosch, South Africa Christians from (Dutch) Reformed backgrounds. The point of entry is two underexplored, Corresponding author: challenging, contextualised crucifixion paintings, namely, Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus. Wilhelm Johannes Verwoerd, Drawing on critical whiteness studies, extensive local and international experience as a [email protected] ‘participatory’ facilitator of conflict transformation and his particular embodiment, the author explores the creative unsettling potential of these two prophetic ‘icons’. Through this Dates: incarnational, phenomenological, diagnostic engagement with Black Christ, attention is drawn Received: 05 Oct. 2019 Accepted: 09 Mar. 2020 to the dynamics of family betrayal, ‘moral injury’ and idolisation underlying ‘white fragility’. Published: 30 July -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

The Anthropology of Space and Place in the Afrikaner Volkstaat Of

“PLACE OF OUR OWN”: The Anthropology of Space and Place In the Afrikaner Volkstaat of Orania by LISE HAGEN submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject ANTHROPOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PRETORIA Supervisor: Professor M. de Jongh Co-supervisor: Professor C.J. van Vuuren January 2013 Student number: 4107-018-6 I declare that “PLACE OF OUR OWN”: The Anthropology of Space and Place in the Afrikaner Volkstaat of Orania is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ___________________ _____________________ Signed Date (Lise Hagen) i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dedicated to Hugo Hagen: father, artist & storyteller extraordinaire Carpe diem pappa Words are inadequate to convey the nuances and myriad facets to each and every step of this research journey. However, I humbly express my sincerest thanks to the following persons and institutions who contributed: The inhabitants, management and leadership of Orania for allowing me a glimpse into their lives. While there were many, many instances of assistance, collaboration and kindness, in particular I would like to thank Karel iv and Anje for food, and food for thought, the Strydoms, Lida and Nikke, for patience and Dr. Manie Opperman, Sebastian Biehl and Roelien de Klerk for their personal interest and support. Dankie Orania. My husband. Geliefde, thanks for accompanying me across the country and across the world, on roads certainly less travelled. To my supervisors Professors Mike de Jongh and Chris van Vuuren for their patient support and for fostering me, an anthropological cuckoo, above and beyond the call of duty.