Ifind No Water Fat Than Stick: to My Own Bones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The Versatile Singer: A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone Danya Katok The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1394 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by DANYA KATOK A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2016 ©2016 Danya Katok All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date L. Poundie Burstein Chair of the Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Philip Ewell, advisor Loralee Songer, first reader Stephanie Jensen-Moulton L. Poundie Burstein Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by Danya Katok Advisor: Philip Ewell Straight tone is a valuable tool that can be used by singers of any style to both improve technical ideals, such as resonance and focus, and provide a starting point for transforming the voice to meet the stylistic demands of any genre. -

Oratorio Society of New York Performing Handel's

Contact: Jennifer Wada Communications 718-855-7101 [email protected] 1440 Broadway, 23rd Floor www.wadacommunications.com New York, NY 10018 212–400–7255 ORATORIO SOCIETY OF NEW YORK PERFORMING HANDEL’S MESSIAH AT CARNEGIE HALL = A NEW YORK TRADITION OF THE HIGHEST ORDER Kent Tritle Conducts OSNY’s 143rd Annual Performance of the Holiday Classic on Wednesday, December 21, 2016, at 8:00 pm Kathryn Lewek, Jakub Józef Orliński, William Ferguson, and Adam Lau are Soloists Kent Tritle leading the Oratorio Society of New York at Carnegie Hall (photo by Tim Dwight) “A vibrant and deeply human performance, made exciting by the sheer heft and depth of the chorus's sound.” -The New York Times (on Messiah) The Oratorio Society of New York has the distinction of having performed Handel’s Messiah every Christmas season since 1874, and at Carnegie Hall every year the hall has been open since 1891 – qualifying the OSNY’s annual rendition of the holiday classic as a New York tradition of the highest order. On Wednesday, December 21, 2016, Music Director Kent Tritle leads the OSNY, New York’s champion of the grand choral tradition, in its 143rd performance of Messiah, at Carnegie Hall. The vocal soloists are Kathryn Lewek, soprano; Jakub Józef Orliński, countertenor; William Ferguson, tenor; and Adam Lau, bass. Oratorio Society of New York’s 143 Performance of Handel’s Messiah – Dec. 21, 2016 - Page 2 of 4 “Each performance is fresh” -Kent Tritle Performing an iconic work such as Messiah every year presents the particular challenge of avoiding settling into a groove. -

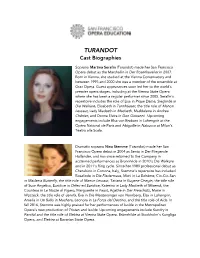

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

The KF International Marcella Sembrich International Voice

The KF is excited to announce the winners of the 2015 Marcella Sembrich International Voice Competition: 1st prize – Jakub Jozef Orlinski, counter-tenor; 2nd prize – Piotr Buszewski, tenor; 3rd prize – Katharine Dain, soprano; Honorable Mention – Marcelina Beucher, soprano; Out of 92 applicants, 37 contestants took part in the preliminary round of the competition on Saturday, November 7th, with 9 progressing into the final round on Sunday, November 8th at Ida K. Lang Recital Hall at Hunter College. This year's competition was evaluated by an exceptional jury: Charles Kellis (Juilliard, Prof. emeritus) served as Chairman of the Jury, joined by Damon Bristo (Vice President and Artist Manager at Columbia Artists Management Inc.), Markus Beam (Artist Manager at IMG Artists) and Dr. Malgorzata Kellis who served as a Creative Director and Polish song expert. About the KF's Marcella Sembrich Competition: Marcella Sembrich-Kochanska, soprano (1858-1935) was one of Poland's greatest opera stars. She appeared during the first season of the Metropolitan Opera in 1883, and would go on to sing in over 450 performances at the Met. Her portrait can be found at the Metropolitan Opera House, amongst the likes of Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, and Giuseppe Verdi. The KF's Marcella Sembrich Memorial Voice Competition honors the memory of this great Polish artist, with the aim of popularizing Polish song in the United States, and discovering new talents (aged 18-35) in the operatic world. This year the competition has turned out to be very successful, considering that the number of contestants have greatly increased and that we have now also attracted a number of International contestants from Japan, China, South Korea, France, Canada, Puerto Rico and Poland. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reexamining Portamento As an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, Ca. 1840-1940 a Disserta

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reexamining Portamento as an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, Ca. 1840-1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Desiree Janene Balfour 2020 © Copyright by Desiree Janene Balfour 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reexamining Portamento as an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, ca. 1840-1940 by Desiree Janene Balfour Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor William A. Kinderman, Co-Chair Professor James K. Bass, Co-Chair This study reexamines portamento as an important expressive resource in nineteenth and twentieth-century Western classical choral music. For more than a half-century, portamento use has been in serious decline and its absence in choral performance is arguably an impoverishment. The issue is encapsulated by John Potter, who writes, “A significant part of the early music agenda was to strip away the vulgarity, excess, and perceived incompetence associated with bizarre vocal quirks such as portamento and vibrato. It did not occur to anyone that this might involve the rejection of a living tradition and that singers might be in denial about their own vocal past.”1 The present thesis aims to show that portamento—despite its fall from fashion—is much more than a “bizarre vocal quirk.” When blended with aspects of the modern aesthetic, 1 John Potter, "Beggar at the Door: The Rise and Fall of Portamento in Singing,” Music and Letters 87 (2006): 538. ii choral portamento is a valuable technique that can enhance the expressive qualities of a work. -

Adelina Patti Galt Als Eine Herausragende Opernsängerin Internationalen Ranges Des Italienischen Belcanto

Patti, Adelina gendste Interpretin des Belcanto, und wenn sie auf der Bühne oder auf dem Podium erschien, löste ihre süße, glockenhelle, glänzend geschulte Stimme das Entzücken der Zuhörer aus. Dazu kam ihre hübsche, zarte Erschei- nung, ein lebhaftes Mienenspiel und feuriges Versenken in ihren Vortrag.“ Pester Lloyd, ”Morgenblatt”, 30. September 1919, 66. Jg., Nr. 183, S. 5. Profil Adelina Patti galt als eine herausragende Opernsängerin internationalen Ranges des italienischen Belcanto. Ne- ben ihrem Gesangsstil wurde auch ihre Schauspielkunst, die von Charme und großer Natürlichkeit geprägt war, ge- rühmt. Orte und Länder Adelina Patti wurde als Kind italienischer Eltern in Mad- rid geboren. Ihre Kindheit verbrachte sie in New York. Nach ihrem Konzertdebut 1851 in dieser Stadt unter- nahm die Sopranistin Konzerttourneen durch Nordame- rika, Kuba, die Karibik, Kanada und Mexiko. Nach ihrem großen Erfolg 1861 in London trat sie in der englischen Musikmetropole regelmäßig über 40 Jahre auf. Auch auf der Pariser Opernbühne war die Sängerin kontinuierlich präsent. Weiterhin unternahm die Künstlerin regelmäßig Tourneen durch ganz Europa und sang in Städten wie Wien, Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, Wiesbaden, Amster- Adelina Patti, Hüftbild von Ch. Reutlinger dam, Brüssel, Florenz, Nizza, Rom, Neapel, Madrid, Liss- abon, Petersburg und Moskau. Mehrere Konzertreisen führten Adelina Patti wiederholt nach Nord -, Mittel- Adelina Patti und Südamerika. 1878 kaufte die Sängerin in Wales das Ehename: Adelina Adela Cederström Schloss „Craig-y-Nos“ wo sie die Zeit zwischen den Varianten: Adelina de Cuax, Adelina Nicolini, Adelina Tourneen verbrachte. Auf diesem Schloss veranstaltete Cederström, Adelina Patti-Nicolini, Adelina Adela Juana die Künstlerin regelmäßig Konzertabende. Maria Patti, Adelina Adela Juana Maria de Cuax, Adelina Adela Juana Maria Nicolini, Adelina Adela Juana Maria Biografie Cederström, Adelina Adela Juana Maria Patti-Nicolini Adelina Patti stammte aus einer Musikerfamilie. -

Progrmne the DURABILITY Of

PRoGRmnE The DURABILITY of PIANOS and the permanence of their tone quality surpass anything that has ever before been obtained, or is possible under any other conditions. This is due to the Mason & Hamlin system of manufacture, which not only carries substantial and enduring construction to its limit in every detail, but adds a new and vital principle of construc- tion— The Mason & Hamlin Tension Resonator Catalogue Mailed on Jtpplication Old Pianos Taken in Exchange MASON & HAMLIN COMPANY Establishea;i854 Opp. Institute of Technology 492 Boylston Street SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON 6-MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES , ( Ticket Office, 1492 J Telephones_, , Back^ ^ Bay-d \ Administration Offices. 3200 \ TWENTY-NINTH SEASON, 1909-1910 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor prngramm^ of % Nineteenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 18 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 19 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A.ELLIS, MANAGER 1417 Mme. TERESA CARRENO On her tour this season will use exclusively j^IANO. THE JOHN CHURCH CO. NEW YORK CINCINNATI CHICAGO REPRESENTED BY 6. L SGHIRMER & CO., 338 Boylston Street, Boston, Mass. Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL |J.M.^w^^w^»l^^^R^^^^^^^wwJ^^w^J^ll^lu^^^^wR^^;^^;^^>^^^>u^^^g,| Perfection in Piano Makinrf THE -^Mamtin Qaartcr Grand Style V, in figured Makogany, price $650 It is tut FIVE FEET LONG and in Tonal Proportions a Masterpiece of piano building^. It IS Cnickering & Sons most recent triumpLi, tke exponent of EIGHTY-SEVEN YEARS experience in artistic piano tuilding, and tlie lieir to all tne qualities tkat tke name of its makers implies. -

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30Pm, Hall

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30pm, Hall The English Concert Harry Bicket conductor/harpsichord Iestyn Davies Rinaldo Jane Archibald Armida Sasha Cooke Goffredo Joélle Harvey Almirena/Siren Luca Pisaroni Argante Jakub Józef Orli ´nski Eustazio Owen Willetts Araldo/Donna/Mago Richard Haughton Richard There will be two intervals of 20 minutes following Act 1 and Act 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we welcome back Harry Bicket as delighted by the extravagant magical and The English Concert for Rinaldo, the effects as by Handel’s endlessly inventive latest instalment in their Handel opera music. And no wonder – for Rinaldo brings series. Last season we were treated to a together love, vengeance, forgiveness, spine-tingling performance of Ariodante, battle scenes and a splendid sorceress with a stellar cast led by Alice Coote. -

List of the Singers Admitted to the Competition

LIST OF THE SINGERS ADMITTED TO THE COMPETITION FIRST NAME SURNAME COUNTRY VOICE TYPE NOTES 1 Gamid Abdulov RUSSIA / AZERBAIJAN baritone Recommendation by The 2 Alina Adamski POLAND soprano International Opera Studio (IOS), Opernhaus Zurich Not evaluated by: Matthias 3 Stefan Astakhov GERMANY baritone Rexroth (according to point II.6 of Selection Panel’s Statute) Not evaluated by: Matthias 4 Dagmara Barna POLAND soprano Rexroth (according to point II.6 of Selection Panel’s Statute) 5 Eliza Boom NEW ZEALAND soprano 6 Paweł Brożek POLAND tenor Not evaluated by: Matthias 7 Monika Buczkowska POLAND soprano Rexroth (according to point II.6 of Selection Panel’s Statute) Prizewinner of Leyla Gencer 8 Piotr Buszewski POLAND tenor Voice Competition 9 Vladislav Buyalskiy UKRAINE bass-baritone Not evaluated by: Matthias 10 Paride Cataldo ITALY tenor Rexroth (according to point II.6 of Selection Panel’s Statute) Recommendation by Opera 11 Anna El-Khashem RUSSIA soprano Studio of the Bayerische Staatsoper 12 Frische Felicitas GERMANY soprano 13 Margrethe Fredheim NORWAY soprano 14 Kseniia Galitskaia RUSSIA soprano 15 Kim Gihoon SOUTH KOREA baritone 16 William Goforth USA tenor Not evaluated by: Matthias Agnieszka 17 Grochala POLAND soprano Rexroth (according to point II.6 Jadwiga of Selection Panel’s Statute) Not evaluated by: Matthias 18 Yuriy Hadzetskyy UKRAINE baritone Rexroth (according to point II.6 of Selection Panel’s Statute) 19 Anna Harvey UK mezzo-soprano Not evaluated by: Matthias 20 Mateusz Hoedt POLAND bass Rexroth (according to point -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

June 1926) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1926 Volume 44, Number 06 (June 1926) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 44, Number 06 (June 1926)." , (1926). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/735 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC STUDY 1 EX AI^TSUFeT i MVS I C die ETVDE MAGA ZINE JUNE 1926 Everything Count, i in Musical Success, by Lawrence Tibbett jZ? Practical Points for Practical Teachers, by C reorg Liebling zZ? Getting Up a School Band, by J. E. Maddy zzz Studying Music Late iri Life, by J. M. Williams zz? Twenty-Four Excellent Pieces, by Wagner, Bolzoni, 1 'riml, Mrs. Beach, Rolfe, Bliss, Krentzlin, Himmelreich, and others JUNE 1926 Page k05 THE ETUDE Just Music Teachers— -Think! Awake to This Real’ Opportunity YOU WHY NOT DEVOTE SOME OF YOUR LEISURE HOURS THIS SUMMER TO CAN CONDUCTING A THEORY CLASS IN YOUR COMMUNITY? HAVE Activity is the best publicity. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Repertory and rivalry : opera and the Second Covent Garden Theatre, 1830-56. Dideriksen, Gabriella The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 Repertory and Rivalry: Opera at the Second Covent Garden Theatre, 1830 to 1856 Gabriella Dlderlksen PhD, Historical Musicology King's College London, University of London June 1997 Abstract Victorian London has hitherto frequently been regarded as an operatic backwater without original musical or theatrical talent, and has accordingly been considered only marginally important to the history of 19th-century opera in general.