Discovery Or Reputation? Jacques Loeb and the Role of Nomination Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diphtheria Serum and Serotherapy. Development, Production and Regulation in Fin De Siècle Germany

Diphtheria serum and serotherapy. Development, Production and regulation in fin de siècle Germany Axel C. Hüntelmann Institute for the History of Medicine, Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg. [email protected] Dynamis Fecha de recepción: 3 de enero de 2007 [0211-9536] 2007; 27: 107-131 Fecha de aceptación: 8 de marzo de 2007 SUMMARY: 1.—Introduction. 2.—The socio-cultural context of science in fin de siècle Germany. 3.— The development of diphtheria serum in Germany. 4.—The production of diphtheria serum in the German Empire. 5.—State control of diphtheria serum. 6.—Serum networks and indirect state regulation. ABSTRACT: The development, production and state regulation of diphtheria serum is outlined against the background of industrialisation, standardization, falling standards of living and rising social conflict in fin de siècle Germany. On one hand, diphtheria serum offered a cure for an infectious disease and was a major therapeutic innovation in modern medicine. On the other hand, the new serum was a remedy of biological origin and nothing was known about its side effects or long-term impact. Moreover, serum therapy promised high profits for manufacturers who succeeded in stabilizing the production process and producing large quantities of serum in so-called industrial production plants. To minimize public health risks, a broad system of state regulation was installed, including the supervision of serum production and distribution. The case of diphtheria serum illustrates the indirect forms of government supervision and influence adopted in the German Empire and the cooperation and networking among science, state and industry. PALABRAS CLAVE: suero antidiftérico, Alemania, regulacion estatal, seroterapia, redes entre ciencia, estado e industria, Emil Behring. -

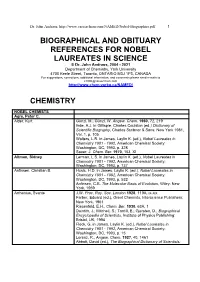

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Commencement1991.Pdf (8.927Mb)

TheJohns Hopkins University Conferring of Degrees At the Close of the 1 1 5th Academic Year MAY 23, 1991 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/commencement1991 Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Johns Hopkins Society of Scholars 10 Honorary Degree Citations 12 Academic Regalia 15 Awards 17 Honor Societies 21 Student Honors 23 Degree Candidates 25 As final action cannot always be taken by the time the program is printed, the lists of candidates, recipients of awards and prizes, and designees for honors are tentative only. The University reserves the right to withdraw or add names. Order ofProcession MARSHALS Sara Castro-Klaren Peter B. Petersen Eliot A. Cohen Martin R. Ramirez Bernard Guyer Trina Schroer Lynn Taylor Hebden Stella M. Shiber Franklin H. Herlong Dianne H. Tobin Jean Eichelberger Ivey James W. Wagner Joseph L. Katz Steven Yantis THE GRADUATES * MARSHALS Grace S. Brush Warner E. Love THE FACULTIES **- MARSHALS Lucien M. Brush, Jr. Stewart Hulse, Jr. THE DEANS MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY THE TRUSTEES CHDZF MARSHAL Noel R. Rose THE VICE PRESIDENT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNDTERSLTY ALUMNI ASSOCIATION THE CHAPLAINS THE PRESENTERS OF THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE INTERIM PROVOST OF THE UNIVERSITY THE CHADIMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNDTERSLTY 1 Order ofEvents William (.. Richardson President of the University, presiding * * « PRELUDE Suite from the American Brass Band Journal G.W.E. Friederich (1821-1885) Suite from Funff— stimmigte blasenda Music JohannPezel (1639-1694) » PROCESSIONAL The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing after the Invocation. -

The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce

The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce Fye New York I March 11, 2019 The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce Fye New York | Monday March 11, 2019, at 10am and 2pm BONHAMS LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE New York Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 Please email bids.us@bonhams. Ian Ehling +1 (212) 644 9001 www.bonhams.com com with “Live bidding” in Director +1 (212) 644 9009 fax the subject line 48 hrs before +1 (212) 644 9094 PREVIEW the auction to register for this [email protected] ILLUSTRATIONS Thursday, March 7, service. Front cover: Lot 188 10am to 5pm Tom Lamb, Director Inside front cover: Lot 53 Friday, March 8, Bidding by telephone will only be Business Development Inside back cover: Lot 261 10am to 5pm accepted on a lot with a lower +1 (917) 921 7342 Back cover: Lot 361 Saturday, March 9, estimate in excess of $1000 [email protected] 12pm to 5pm REGISTRATION Please see pages 228 to 231 Sunday, March 10, Darren Sutherland, Specialist IMPORTANT NOTICE for bidder information including +1 (212) 461 6531 12pm to 5pm Please note that all customers, Conditions of Sale, after-sale [email protected] collection and shipment. All irrespective of any previous activity SALE NUMBER: 25418 with Bonhams, are required to items listed on page 231, will be Tim Tezer, Junior Specialist complete the Bidder Registration transferred to off-site storage +1 (917) 206 1647 CATALOG: $35 Form in advance of the sale. -

Metchnikoff and the Phagocytosis Theory

PERSPECTIVES TIMELINE Metchnikoff and the phagocytosis theory Alfred I. Tauber Metchnikoff’s phagocytosis theory was less century. Indeed, the clonal selection theory and an explanation of host defence than a the elucidation of the molecular biology of the proposal that might account for establishing immune response count among the great and maintaining organismal ‘harmony’. By advances in biology during our own era5. tracing the phagocyte’s various functions Metchnikoff has been assigned to the wine cel- Figure 1 | Ilya Metchnikoff, at ~45 years of through phylogeny, he recognized that eating lar of history, to be pulled out on occasion and age. This figure is reproduced from REF. 14. the tadpole’s tail and killing bacteria was the celebrated as an old hero. same fundamental process: preserving the However, to cite Metchnikoff only as a con- integrity, and, in some cases, defining the tributor to early immunology distorts his sem- launched him into the turbulent waters of evo- identity of the organism. inal contributions to a much wider domain. lutionary biology. He wrote his dissertation on He recognized that the development and func- the development of invertebrate germ layers, I first encountered the work of Ilya tion of the individual organism required an for which he shared the prestigious van Baer Metchnikoff (1845–1916; FIG. 1) in Paul de understanding of physiology in an evolution- Prize with Alexander Kovalevski. By the age of Kruif’s classic, The Microbe Hunters 1.Who ary context. The crucial precept: the organism 22 years, he was appointed to the position of would not be struck by the description of this was composed of various elements, each vying docent at the new University of Odessa, where, fiery Russian championing his theory of for dominance. -

Allergy – What’S in a Name?

HISTORY OF ENT Allergy – what’s in a name? BY KATHERINE CONROY llergy is defined as an “abnormal immune reaction to an ordinarily harmless substance” [1], however Athe meaning of the word has taken many forms since its introduction in 1906 by Austrian Paediatrician and Immunologist, Clemens von Pirquet [2]. Combining his observations on the paediatric wards, where infectious diseases, vaccinations and diphtheria serum sickness were commonplace, and his knowledge of immune reactions in the laboratory, von Pirquet devised the term ‘allergy’, roughly translating as ‘different reaction’ in Greek. It grouped together illnesses such as asthma, hay fever and eczema, and placed them on the same spectrum as acquired immunity from vaccinations and reactions to therapeutic toxins. His conclusions were extrapolated by Charles Mantoux to develop his tuberculin test two years later. Unfortunately, this theory linking Clemens von Pirquet with a patient. Image courtesy of Wellcome Collection - https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yd78ffbn immunity and hypersensitivity, and von Piquet’s subsequent inference that antibodies could be both protective and also include morbidity – as governments References 1. AAAAI. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma harmful, was dismissed by many of his peers, realised the economic cost of chronic illness. Allergy became a clinical specialty in its & Immunology. www.aaaai.org/conditions-and- who instead supported French Physiologist, treatments/conditions-dictionary/allergy Last Charles Richet. Richet’s work on reinjection own right, with dedicated clinics, journals accessed October 2020. of dogs with sea anemone toxins showed and professional organisations in the 2. Jackson M. Allergy, The History of a Modern Malady. that a small, second dose could induce a interwar years. -

Consciousness Eclipsed: Jacques Loeb, Ivan P. Pavlov, and the Rise of Reductionistic Biology After 1900

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 14 (2005) 219–230 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog Consciousness eclipsed: Jacques Loeb, Ivan P. Pavlov, and the rise of reductionistic biology after 1900 Ralph J. Greenspan*, Bernard J. Baars The Neurosciences Institute, 10640 John Jay Hopkins Dr., San Diego, CA 92121, United States Received 17 May 2004 Available online 25 November 2004 Abstract The life sciences in the 20th century were guided to a large extent by a reductionist program seeking to explain biological phenomena in terms of physics and chemistry. Two scientists who figured prominently in the establishment and dissemination of this program were Jacques Loeb in biology and Ivan P. Pavlov in psychological behaviorism. While neither succeeded in accounting for higher mental functions in physical- chemical terms, both adopted positions that reduced the problem of consciousness to the level of reflexes and associations. The intellectual origins of this view and the impediment to the study of consciousness as an object of inquiry in its own right that it may have imposed on peers, students, and those who followed is explored. Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: History of ideas; Reductionism; Tropism; Conditional reflex 1. Introduction The current acceptance of consciousness as a suitable object of study in the life sciences came late in the 20th century (Flanagan, 1984). By that time other biological processes—physiology, biochemistry, genetics, embryology, and even many aspects of brain function—had long since * Corresponding author. Fax: +1 858 626 2099. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (R.J. Greenspan), [email protected] (B.J. -

Dissociation and the Unconscious Mind: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on Mediumship

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 537–596, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Dissociation and the Unconscious Mind: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on Mediumship C!"#$% S. A#&!"!'$ Parapsychology Foundation [email protected] Submitted December 18, 2019; Accepted March 21, 2020; Published September 15, 2020 https://doi.org/10.31275/20201735 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—There is a long history of discussions of mediumship as related to dissociation and the unconscious mind during the nineteenth century. A! er an overview of relevant ideas and observations from the mesmeric, hypnosis, and spiritualistic literatures, I focus on the writings of Jules Baillarger, Alfred Binet, Paul Blocq, Théodore Flournoy, Jules Héricourt, William James, Pierre Janet, Ambroise August Liébeault, Frederic W. H. Myers, Julian Ochorowicz, Charles Richet, Hippolyte Taine, Paul Tascher, and Edouard von Hartmann. While some of their ideas reduced mediumship solely to intra-psychic processes, others considered as well veridical phenomena. The speculations of these individuals, involving personation, and di" erent memory states, were part of a general interest in the unconscious mind, and in automatisms, hysteria, and hypnosis during the period in question. Similar ideas continued into the twentieth century. Keywords: mediumship; dissociation; secondary personalities; Frederic W. H. Myers; Théodore Flournoy; Pierre Janet INTRODUCTION Dissociation, a process involving the disconnection of a sense of identity, physical sensations, and memory from conscious experience, has been related to mediumship due to the latter’s sensory and motor automatism and changes of identity. In recent years there have been some conceptual discussions of dissociation and mediumship (e.g., Maraldi et al., 2019) as well as empirical studies exploring their 538 Carlos S. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

Carl Gegenbaur – Wikipedia

Carl Gegenbaur – Wikipedia http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Gegenbaur aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Carl Gegenbaur (* 21. August 1826 in Würzburg; † 14. Juni 1903 in Heidelberg) war ein deutscher Arzt, einer der bedeutendsten Wirbeltiermorphologen des 19. Jahrhunderts und einer der Väter der Evolutionsmorphologie, eines modernen Begriffs von Walter J. Bock und Dwight D. Davis. 1 Leben 2 Wissenschaftliche Leistung 2.1 Das „Kopf-Problem“ 3 Verhältnis Carl Gegenbaur und Ernst Haeckel 4 Nach Gegenbaur benannte Taxa Carl Gegenbaur 5 Ausgewählte Arbeiten 6 Weiterführende Literatur 7 Weblinks 8 Einzelnachweise Er war der Sohn des Justizbeamten Franz Joseph Gegenbaur (1792–1872) und dessen Ehefrau Elisabeth Karoline (1800–1866), geb. Roth. Von seinen sieben Geschwistern verstarben vier sehr jung; sein um drei Jahre jüngerer Bruder wurde nur 25 Jahre und seine um 13 Jahre jüngere Schwester 38 Jahre alt.[1] 1838 besuchte er die Lateinschule und von 1838 bis 1845 in Würzburg das Gymnasium. Schon zu seiner Schulzeit führt er Naturstudien in der Umgebung von Würzburg und bei Verwandten im Odenwald (Amorbach) durch. Er beschäftigt sich weiterführend mit Pflanzen, Tieren, Gesteinen, legte Sammlungen an, fertigte Zeichnungen und führte erste Tiersektionen durch.[2] Politische Hintergründe: Bayern wurde 1806 unter dem Minister Maximilian Carl Joseph Franz de Paula Hieronymus Graf von Montgelas (1759–1838) zu einem der führenden Mitglieder im Rheinbund und Bündnispartner von Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821). Für seine Bündnistreue wurde im Frieden von Pressburg Bayern zum Königreich durch den französischen Kaiser aufgewertet und Herzog Maximilian IV. (1756–1825) am 1. Januar 1806 in München als Maximilian I. Joseph zum ersten König Bayerns erhoben. -

Centenary of the Death of Elie Metchnikoff: a Visionary and an Outstanding Team Leader

+ MODEL Microbes and Infection xx (2016) 1e18 www.elsevier.com/locate/micinf Review Centenary of the death of Elie Metchnikoff: a visionary and an outstanding team leader Jean-Marc Cavaillon a,*, Sandra Legout b a Unit Cytokines & Inflammation, Institut Pasteur, 28 Rue Dr. Roux, 75015 Paris, France b Centre de Ressources en Information Scientifique, Institut Pasteur, 28 Rue Dr. Roux, 75015 Paris, France Received 22 April 2016; accepted 26 May 2016 Available online ▪▪▪ Abstract Elie Metchnikoff passed away on July 15th, 1916. He is considered to be the father of phagocytes, cellular innate immunity, probiotics, and gerontology. In all of these fields, he was a visionary. To achieve such a notability and produce so many masterpieces, Metchnikoff used more than 30 animal species to support his findings, and his pasteurian laboratory published more than 200 papers in the Annales de l’Institut Pasteur. As a wonderful team leader and a great mentor, during his 28 years at Institut Pasteur, he welcomed and supervised more than 100 young trainees. Trained as an embryologist, he contributed to the birth of immunology and to the understanding of physiology and pathology. Indeed, Metchnikoff and his team investigated inflammation in guinea pigs, rats, frogs; studied infectious diseases in monkeys, caimans, geese; investigated aging in parrots, dogs, humans; proposed hypotheses to understand age-associated senility using rabbits and humans; developed germ free tadpoles, flies, chicks; studied the gut flora in bats, horses, birds, humans; and popularized the use of probiotics as a tool to delay the deleterious effects of toxic compounds derived from putrefactive gut bacteria. -

The Rockefeller University Story

CASPARY AUDITORIUM AND FOUNTAINS THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY STORY THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY STORY JOHN KOBLER THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY PRESS· 1970 COPYRIGHT© 1970 BY THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY PRESS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUE CARD NO. 76-123050 STANDARD BOOK NO. 8740-015-9 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION The first fifty years of The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research have been recorded in depth and with keen insight by the medical his torian, George W. Corner. His story ends in 1953-a major turning point. That year, the Institute, which from its inception had been deeply in volved in post-doctoral education and research, became a graduate uni versity, offering the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to a small number of exceptional pre-doctoral students. Since 1953, The Rockefeller University's research and education pro grams have widened. Its achievements would fill a volume at least equal in size to Dr. Corner's history. Pending such a sequel, John Kobler, a journalist and biographer, has written a brief account intended to acquaint the general public with the recent history of The Rockefeller University. Today, as in the beginning, it is an Institution committed to excellence in research, education, and service to human kind. FREDERICK SEITZ President of The Rockefeller University CONTENTS INTRODUCTION V . the experimental method can meet human needs 1 You, here, explore and dream 13 There's no use doing anything for anybody until they're healthy 2 5 ... to become scholarly scientists of distinction 39 ... greater involvement in the practical affairs of society 63 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 71 INDEX 73 .