Defining the York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James River Geography

James River Geography Welcome to NOAA's James River Interpretive Buoy, located at latitude 37 degrees 12.25 minutes North, longitude 76 degrees 46.65 minutes West. It lies off Jamestown Island about a quarter-mile south of Captain John Smith's statue, where he can see it well as he looks out over the river. This buoy is anchored in 43 feet of water at the edge of the narrow shoal that runs along the island. The river's channel is deep here, as the James narrows down between Swanns Point on the south and Jamestown on the north, but it quickly shoals as it sweeps through the broad meander curve from Cobham Bay around Hog Island and down toward Burwell Bay. The buoy lies about thirty miles above the mouth of the James at Hampton Roads. Jamestown Island lies at a transition point on the James. Five miles upstream is the mouth of the Chickahominy River, which adds a strong current of fresh water to the heavy flow already coming out of the James watershed from deep in Virginia's uplands, the mountains at the eastern edge of the Alleghany Plateau. In wet years, the water here is nearly fresh. The mouth of the James, however, lies close to the Chesapeake's mouth, so salt water can also flow upriver with the tides. In John Smith's time here, the region suffered a multi-year drought, so the river and the colonists' drinking water was probably brackish, an irritating factor that may account for some of the bickering and poor health that plagued them. -

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 984 One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Wednesday, the third day of January, two thousand and eighteen An Act To extend Federal recognition to the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Chickahominy Indian Tribe—Eastern Division, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, Inc., the Monacan Indian Nation, and the Nansemond Indian Tribe. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents of this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. TITLE I—CHICKAHOMINY INDIAN TRIBE Sec. 101. Findings. Sec. 102. Definitions. Sec. 103. Federal recognition. Sec. 104. Membership; governing documents. Sec. 105. Governing body. Sec. 106. Reservation of the Tribe. Sec. 107. Hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, and water rights. TITLE II—CHICKAHOMINY INDIAN TRIBE—EASTERN DIVISION Sec. 201. Findings. Sec. 202. Definitions. Sec. 203. Federal recognition. Sec. 204. Membership; governing documents. Sec. 205. Governing body. Sec. 206. Reservation of the Tribe. Sec. 207. Hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, and water rights. TITLE III—UPPER MATTAPONI TRIBE Sec. 301. Findings. Sec. 302. Definitions. Sec. 303. Federal recognition. Sec. 304. Membership; governing documents. Sec. 305. Governing body. Sec. 306. Reservation of the Tribe. Sec. 307. Hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, and water rights. -

The Archaeology of Virginia's Long Seventeenth Century, 1550-1720: Previous Research and Future Directions

The Archaeology of Virginia's Long Seventeenth Century, 1550-1720: Previous Research and Future Directions Dennis J. Pogue Time Line x 1561-66: Spanish expeditions from Havana and La Florida explore the Chesapeake Bay in search of trade routes to the west and to scout potential sites for settlement. x 1570: Jesuit priests establish the Ajacan mission on the York River in an attempt to Christianize the native Indians; the venture fails the next year when the priests are killed by the natives. x 1607: The English establish their first permanent settlement in Virginia when 104 colonists disembark at Jamestown Island and erect James Fort. x 1607-08: John Smith and his crew explore the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries by boat; the Englishmen record the locations of the Indian settlements they pass. x 1609-14: Colonists and the Powhatan Indians engage in a series of armed conflicts as the natives attempt to protect their rights to the land. x 1614: English settlers begin to cultivate tobacco, which becomes the primary source of wealth for the colony for the next 200 years. x 1617-22: Twenty-three "particular plantations," or subsidiary corporations controlled by stock holders, are created as part of an attempt to encourage immigration and the spread of settlement beyond Jamestown. x 1619: The first enslaved Africans are introduced to Virginia; the first representative legislative assembly is formed. x 1622: 200,000 pounds of tobacco are shipped out of Virginia; the homes of 1500 settlers spread for 50 miles along the James River; in response to the pressures of continued immigration of Englishmen, the Powhatan Indians attack and kill several hundred settlers in a series of coordinated attacks. -

Indian Women and the Law, 1830 to 1934 Bethany Berger University of Connecticut School of Law

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1997 After Pocahontas: Indian Women and the Law, 1830 to 1934 Bethany Berger University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Berger, Bethany, "After Pocahontas: Indian Women and the Law, 1830 to 1934" (1997). Faculty Articles and Papers. 113. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/113 +(,121/,1( Citation: 21 Am. Indian L. Rev. 1 1997 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Tue Aug 16 12:47:23 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0094-002X AFTER POCAHONTAS: INDIAN WOMEN AND THE LAW, 1830 TO 1934 Bethany Ruth Berger* Table of Contents I. Introduction . ..................................... 2 II. The Nineteenth Century and Indian Women: Federal Indian Policy and the Cult of True Womanhood ....................... 6 I. Federal and State Governments and Indian Women: As Them- selves, as Mothers, and as Wives ...................... 12 A. The Beginning: Ladiga's Heirs and Indian Women in Their Own Right ...................................... 12 B. Indian Women as Wives and Mothers: Intermarriage and Beyond . ........................................ 22 1. A Not So Brief Note on Intermarriage ................. 23 2. -

Pocahontas's Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty

言語・地域文化研究 第 ₂6 号 2020 103 Pocahontas’s Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty Hiroyuki Tsukada ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ 塚田 浩幸 要 旨 ポカホンタスは、二度、ジョン・スミスの命を救った。一度目は有名な助命で、1607 年 12 月、インディアンの首長パウハタンによる処刑の寸前に、ポカホンタスが捕虜スミ スに自分の体をなげうって助命をした。これは、スミスの死と生まれ変わりを象徴的に 意味し、入植者をインディアンの世界に迎え入れる儀式で、ポカホンタスはスミスを救 うというあらかじめ決められた役割を担った。この一度目の助命の真偽については長ら く論争が行なわれてきたが、スミスが 1608 年 6 月の報告書簡でポカホンタスを「比類な き人物」と高く評価できたという事実は、助命が実際に起きたことを示している。その 6 月の時点で、スミスは助命の他に、取引や物資の提供と人質解放交渉の場面でポカホ ンタスと会う機会を持っていたが、それらの場面においては、スミスが「比類なき人物」 と評価することができるほどの行動をポカホンタスがとっていなかったからである。そ して、スミスがその報告書簡でポカホンタスを紹介したのは、入植事業の宣伝のために インディアンとの平和友好をアピールするねらいがあった。つまり、スミスに批判的な 研究者が主張するように、スミスがポカホンタスの人気にあやかって自分の名声をあげ るために助命を捏造したのではなく、助命に感銘を受けたスミスがポカホンタスの人気 を作り上げたといえるのである。 パウハタンは、一度目の助命でポカホンタスをインディアンと入植者の平和友好のシ ンボルとして仕立て上げ、その後の平和的な外交の場面にもポカホンタスを同行させて いた。しかしながら、二度目の助命は、パウハタンの外交方針に逆らって、ポカホンタ ス自身の意思によって行なわれた。1609 年 1 月、インディアンと入植者の関係が悪化す るなか、パウハタンがスミスを本当に襲おうとしているところをポカホンタスがスミス に密告して救った。この二つの助命のあいだの期間、ポカホンタスは入植者と頻繁に会 うなかで理解を深め、パウハタン連合のインディアンとしての忠誠心に揺らぎを生じさ せていたのである。つまり、ポカホンタスは、単なるパウハタンの遣いとしての平和友 好のシンボルであることをやめ、自らを平和友好の使者として確立させるに至ったので ある。 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示 4.0 国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 104 論文 ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ (塚田 浩幸) Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. A special relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith 3. Refutation of all existing theories 4. Demonstration of the veracity of the rescue 5. Conclusion 1. Introduction Pocahontas saved John Smith twice. The frst instance came in December 1607, when she symbolically ofered her own head to save Smith’s -

MAAC 2012 Preliminary Program Virginia Beach, VA March 23-25 8

MAAC 2012 Preliminary Program March 23-25 Virginia Beach, VA Friday Morning, March 23 Track A Session 1: Archaeology of the 20th Century: Addressing the Recent Past Organized by Richard L. Geurcin (USDA Forest Service) 8:30 AM 8:50 AM Towards an Understanding of the 20th Century Guercin, Richard J. (USDA Forest Service) 8:50 AM 9:10 AM Finding the 20th Century Inside the 18th: Archaeology at Ogborne, Jennifer (College of William and the Menokin Site Mary/DATA Investigations, LLC) 9:10 AM 9:30 AM Deterioration and Rehabilitation of the Infrastructure on O Palus, Matthew (The Ottery Group) and P Streets in the Georgetown Neighborhood of Washington, D.C. 9:30 AM 9:50 AM The Missing Pieces of the 20th Century: Excavations at the Moore, Elizabeth A. (Virginia Museum of Natural Gravely House History) 9:50 AM 10:05 AM Break 10:05 AM 10:25 AM An Early Twentieth Century Ceramic Assemblage from a Garrow, Patrick H. (Cultural Resource Analysts, Burned House in Northern Georgia Inc.) 10:25 AM 10:45 AM From Timber to Town to Timber Again: The Story of the Barile , Kerri S. (Dovetail Cultural Resource Kress Box Factory in Brunswick, Virginia Group) and Kerry S. González (Dovetail Cultural Resource Group) 10:45 AM 11:05 AM A steppingstone of civilization”: The Hojack Swing Bridge Somerville, Kyle (University at Buffalo) and and Structures of Power in Monroe County, Western New Christopher Barton (Temple University) York State 11:05 AM 11:25 AM In Harm’s Way: The Hazard’s of Archaeological Field Madden, Michael (USDA Forest Service) Work Involving 20th Century Military Sites 11:25 AM 11:45 AM Saving the Present for the Future’s Past: Documenting Orr, David G. -

The Lincoln- Mcclellan Relationship in Myth and Memory

The Lincoln- McClellan Relationship in Myth and Memory MARK GRIMSLEY Like many Civil War historians, I have for many years accepted invita- tions to address the general public. I have nearly always tried to offer fresh perspectives, and these have generally been well received. But almost invariably the Q and A or personal exchanges reveal an affec- tion for familiar stories or questions. (Prominent among them is the query “What if Stonewall Jackson had been present at Gettysburg?”) For a long time I harbored a private condescension about this affec- tion, coupled with complete incuriosity about what its significance might be. But eventually I came to believe that I was missing some- thing important: that these familiar stories, endlessly retold in nearly the same ways, were expressions of a mythic view of the Civil War, what the amateur historian Otto Eisenschiml memorably labeled “the American Iliad.”1 For Eisenschiml “the American Iliad” was merely a clever title for a compendium of eyewitness accounts of the conflict, but I take the term seriously. In Homer’s Iliad the anger of Achilles, the perfidy of Agamemnon, the doomed gallantry of Hector—and the relationships between them—have enormous, uncontested, unchanging, and almost primal symbolic meaning. So too do certain figures in the American Iliad. Prominent among these are the butcher Grant, the Christ-like Lee, and the rage- filled Sherman. I believe that the traditional Civil War narrative functions as a national myth of central importance to our understanding of ourselves as Americans. And like the classic mythologies of old, it contains timeless wisdom about what it means to be a human being. -

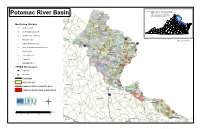

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

Living with the Indians.Rtf

Living With the Indians Introduction Archaeologists believe the American Indians were the first people to arrive in North America, perhaps having migrated from Asia more than 16,000 years ago. During this Paleo time period, these Indians rapidly spread throughout America and were the first people to live in Virginia. During the Woodland period, which began around 1200 B.C., Indian culture reached its highest level of complexity. By the late 16th century, Indian people in Coastal Plain Virginia, united under the leadership of Wahunsonacock, had organized themselves into approximately 32 tribes. Wahunsonacock was the paramount or supreme chief, having held the title “Powhatan.” Not a personal name, the Powhatan title was used by English settlers to identify both the leader of the tribes and the people of the paramount chiefdom he ruled. Although the Powhatan people lived in separate towns and tribes, each led by its own chief, their language, social structure, religious beliefs and cultural traditions were shared. By the time the first English settlers set foot in “Tsenacommacah, or “densely inhabited land,” the Powhatan Indians had developed a complex culture with a centralized political system. Living With the Indians is a story of the Powhatan people who lived in early 17th-century Virginia—their social, political, economic structures and everyday life ways. It is the story of individuals, cultural interactions, events and consequences that frequently challenged the survival of the Powhatan people. It is the story of how a unique culture, through strong kinship networks and tradition, has endured and maintained tribal identities in Virginia right up to the present day. -

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J. Schechner (Cambridge MA) Let me tell you a tale of intrigue and ingenuity, savagery and foreign shores, sex and scientific instruments. No, it is not “Desperate Housewives,” or “CSI,” but the “Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial.”1 As our story opens in 1607, we find Captain John Smith paddling upstream through the Virginia wilderness, when he is ambushed by Indians, held prisoner, and repeatedly threatened with death. His life is spared first by the intervention of his magnetic compass, whose spinning needle fascinates his captors, and then by Pocahontas, the chief’s sexy daughter. At least that is how recent movies and popular writing tell the story.2 But in fact the most famous compass in American history was more than a compass – it was a pocket sundial – and the Indian princess was no seductress, but a mere child of nine or ten years, playing her part in a shaming ritual. So let us look again at the legend, as told by John Smith himself, in order to understand what his instrument meant to him. Who was John Smith?3 When Smith (1580-1631) arrived on American shores at the age of twenty-seven, he was a seasoned adventurer who had served Lord Willoughby in Europe, had sailed the Mediterranean in a merchant vessel, and had fought for the Dutch against Spain and the Austrians against the Turks. In Transylvania, he had been captured and sold as a slave to a Turk. The Turk had sent Smith as a gift to his girlfriend in Istanbul, but Smith escaped and fled through Russia and Poland.