Dehumanization in Oz: the Scarecrow and Tin Man Mimics, the Lion Cannibal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emerald City of Oz by L. Frank Baum Author of the Road to Oz

The Emerald City of Oz by L. Frank Baum Author of The Road to Oz, Dorothy and The Wizard in Oz, The Land of Oz, etc. Contents --Author's Note-- 1. How the Nome King Became Angry 2. How Uncle Henry Got Into Trouble 3. How Ozma Granted Dorothy's Request 4. How The Nome King Planned Revenge 5. How Dorothy Became a Princess 6. How Guph Visited the Whimsies 7. How Aunt Em Conquered the Lion 8. How the Grand Gallipoot Joined The Nomes 9. How the Wogglebug Taught Athletics 10. How the Cuttenclips Lived 11. How the General Met the First and Foremost 12. How they Matched the Fuddles 13. How the General Talked to the King 14. How the Wizard Practiced Sorcery 15. How Dorothy Happened to Get Lost 16. How Dorothy Visited Utensia 17. How They Came to Bunbury 18. How Ozma Looked into the Magic Picture 19. How Bunnybury Welcomed the Strangers 20. How Dorothy Lunched With a King 21. How the King Changed His Mind 22. How the Wizard Found Dorothy 23. How They Encountered the Flutterbudgets 24. How the Tin Woodman Told the Sad News 25. How the Scarecrow Displayed His Wisdom 26. How Ozma Refused to Fight for Her Kingdom 27. How the Fierce Warriors Invaded Oz 28. How They Drank at the Forbidden Fountain 29. How Glinda Worked a Magic Spell 30. How the Story of Oz Came to an End Author's Note Perhaps I should admit on the title page that this book is "By L. Frank Baum and his correspondents," for I have used many suggestions conveyed to me in letters from children. -

The Cowardly Lion

2. “What a mercy that was not a pike!” a. Who said this? b. What do you think would a pike have done to Jeremy? Ans: a. Jeremy said this. b. A pike would have eaten Jeremy. THE COWARDLY LION A. Answer in brief. 1. Where were Dorothy and her friends going and why? Ans: Dorothy and her friends, the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, were walking through the thick woods to reach the Emerald City to meet the Great Wizard of Oz. 2. What did the Cowardly Lion do to the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman while they were walking through the forest? Ans: With one blow of his paw,the Cowardly Lion sent the Scarecrow spinning over and over to the edge of the road. Then he struck at the Tin Woodman with his sharp claws. 3. Why did the Cowardly Lion decide to go with them and what did they all do? Ans: The lion wanted to ask Oz to give him courage as his life was simply unbearable without a bit of courage. So, they set off upon the journey, the Cowardly Lion walking by Dorothy’s side. B. Answer in detail. 1. What did the lion reply when Dorothy asked him why he was a coward? Ans: When Dorothy asked him why he was a coward, the lion said that it was a mystery. He felt he might have been born that way. He learned that if he roared very loudly, every living thing was frightened and got away from him. But whenever there was danger, his heart began to beat fast. -

THE WACKY WIZARD of OZ by Patrick Dorn

THE WACKY WIZARD OF OZ By Patrick Dorn Copyright © 2015 by Patrick Dorn, All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-60003-837-2 CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this Work is subject to a royalty. This Work is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention. RIGHTS RESERVED: All rights to this Work are strictly reserved, including professional and amateur stage performance rights. Also reserved are: motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information and storage retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into non-English languages. PERFORMANCE RIGHTS AND ROYALTY PAYMENTS: All amateur and stock performance rights to this Work are controlled exclusively by Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. No amateur or stock production groups or individuals may perform this play without securing license and royalty arrangements in advance from Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Questions concerning other rights should be addressed to Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice. Professional and stock fees will be set upon application in accordance with your producing circumstances. Any licensing requests and inquiries relating to amateur and stock (professional) performance rights should be addressed to Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Royalty of the required amount must be paid, whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Wicked's Elphaba

“IT’S JUST THAT FOR THE FIRST TIME, I FEEL… WICKED”: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF WICKED’S ELPHABA USING KENNETH BURKE’S GUILT-PURIFICATION-REDEMPTION CYCLE by Patricia C. Foreman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication Studies at Liberty University May 2013 Foreman 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, to “my Dearest, Darlingest Momsy and Popsicle,” and to my brother Gary, thank you so much for your constant support, encouragement, direction and love. I appreciate your words of wisdom and advice that always seem to be just what I need to hear. To each of my fellow graduate assistants, thank you for “dancing through life” with me. Thank you for becoming not only co-workers, but also some of my best friends. To my thesis committee – Dr. William Mullen, Dr. Faith Mullen, and Dr. Lynnda S. Beavers – thank you all so much for your help. This finished thesis is, without a doubt, the “proudliest sight” I’ve ever seen, and I thank you for your time, effort and input in making this finished product a success. Finally, to Mrs. Kim, and all of my fellow “Touch of Swing”-ers, who inspired my love of the Wicked production, and thus, this study. For the long days of rehearsals, even longer nights on tour buses, and endless hours of memories that I’ll not soon forget... “Who can say if I’ve been changed for the better? I do believe I have been changed for the better. And because I knew you, I have been changed for good.” Foreman 3 In Memory Of… Lauren Tuck May 14, 1990 – September 2, 2010 “It well may be that we will never meet again in this lifetime, so let me say before we part, so much of me is made of what I learned from you. -

Wizard of Oz Red 2Bused.Fdx

The Wizard of OZ __________________________ a LINX adaptation RED CAST LINX 141 LINDEN ST. WELLESLEY, MA 01746 (781) 235-3210 [email protected] PROLOGUE [ALL] GLINDA GREETS THE AUDIENCE CURTAIN OPENS. Behind the curtain is GLINDA. She looks at the audience with wonder.] GLINDA_PP What a wonderful audience. So many excited and eager faces. Are we all ready for an adventure? Watch one another’s back now. Things do sneak up on you in Oz. Fortunately, they can be very nice things... (points to back of house) Like that... 1ST SONG - FIREWORK ACT I, SCENE 1 [PP] IN WHICH DOROTHY IS CALLED BEFORE THE WIZARD. CHARACTERS: WIZARD, DOROTHY, SCARECROW, LION, TIN MAN [Head of Wizard hovers before audience. Below, Dorothy, Scarecrow, Lion and Tin Man tremble in terror. Mid-runner curtain is closed behind them. Also onstage is a booth with a hanging curtain. Thick ducts branch out from the booth.] WIZARD I am the great and powerful OZ! Who dares approach me? [Scarecrow, Lion and Tin Man shove Dorothy forward. Dorothy looks back at them.] SCARECROW_PP You got this. LION_PP We’re right behind you. [Dorothy turns toward Wizard. Scarecrow, Lion and Tin Man shuffle backwards. Dorothy turns to them, noticing the increased distance.] TIN MAN_PP Right behind you! 2. WIZARD (to Dorothy) Who are you? DOROTHY_PP My name is Dorothy. Dorothy Gale. WIZARD And where do you come from, “Dorothy Gale”? DOROTHY_PP Kansas. WIZARD Kansas? (long pause) What is Kansas? DOROTHY_PP It’s a place. My home - and I so want to return. A tornado picked up my home, picked up me and my little dog - only, he’s not so little anymore. -

3495 N. Victoria, Shoreview, Mn 55126

3495 N. VICTORIA, SHOREVIEW, MN 55126 WWW.STODILIA.ORG FEBRUARY 26, 2017 * 8TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME PRAYERS FOR THE SICK OUR PARISH COMMUNITY Jerry Ciresi, Doug Miller, Tiffany Pohl, Laure Waschbusch, Patricia Pfenning-Wendt, Jerry Bauer, Mary Ellen Suwan, NEW PARISHIONER BRIEFINGS & WELCOME Jim Andal, Lee & Virginia Johnson, Louise Simon, Michael Would you like to join the parish? Mrugala, Rosemary Vetsch, Agnes Walsh, Bertha Karth, The New Parishioner Briefings are: Zoey McDonald, Elizabeth Bonitz, Lorraine Kadlec, • Thurs., March 9 at 7:00pm in Rm.1302 • Elizabeth Waschbusch, Jim Czeck, Barbara Dostert, Steve Sun., March 19 after the 9:00am Mass in Rm. 1302 Pasell, Craig Monson, Colt Moore, Pat Keppers, Marian We will welcome new parishioners (who have already at- Portesan, Glenn Schlueter, Alan Kaeding, Helen and Lowell tended a briefing) at the 9:00am Mass and Reception next Carlen, Mary Donahue, Pat Kassekert, Bob Rupar, Emma Sunday, March 5, 2017. Please give them a warm wel- Tosney, Bernadette Valento, Philippa Lindquist, Trevor come! Pictures of our new members are posted on the par- Ruiz, Steve Lauinger, Linda Molenda, Michael Carroll, John ish bulletin board in the school hallway. Gravelle, Lynn Latterell, Harry Mueller, Haley Crain, Joan SOCIAL JUSTICE CORNER Rourke, Mary Lakeman, John Lee, Romain Hamernick, The Dignity of each Person - “What did you call me?” Marlene Dirkes, Clementine Brown, Lynn Schmidt, Donna by Hosffman Ospino, Assistant Professor of Hispanic Ministry and Heins, Kelly & Emilia Stein, Bob Zermeno, Joan Kurkowski, Religious Education, Boston College School of Theology Educa- Joan Kelly, Erin Joseph, Patricia Wright. Help us keep this tion. -

Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman, Lion, Oz Setting: Dorothy, Toto, Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman and Lion Are in the Throne Room of Oz for the First Time

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Audition Lines Reading 1 Characters: Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman, Lion, Oz Setting: Dorothy, Toto, Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman and Lion are in the throne room of Oz for the first time. OZ: (A large painted face appears above a green screen. The voice is loud and frightening.) I am Oz, the Great and Terrible. Who are you, and why do you seek me? DOROTHY: I am Dorothy, the Small and Meek. OZ: Where did you get the ruby slippers? DOROTHY: I got them from the Wicked Witch of the East when my house fell on her. Oh, please, Your Honor, send me back to Kansas where my Aunt Em is. I’m sure she’ll be worried over my being away so long. OZ: Silence!!! (Alarmed, Dorothy steps right, Toto follows.) Step forward, Tin Woodsman! TIN WOODSMAN: (Gulping in fear.) Yes, Your Wizardship? OZ: What do you seek from the great and terrible Oz, you miserable pile of clanking junk! (Lion and Scarecrow are about to faint. Tin Woodsman isn’t doing much better. His knees are knocking.) TIN WOODSMAN: I have no heart. Please give me a heart that I may be as other men are. (He drops to his knees, implores.) Please, please, oh, great and terrible Oz! OZ: Silence!!! (Tin Woodsman scurries back to others on his knees.) Step forward, Scarecrow! SCARECROW: (Moves out, his wobbly arms and legs moving in all directions at once.) If I had any brains I’d be terrified. OZ: So, it’s brains you want, you poor excuse for a crow’s nest. -

"The Patchwork Girl of Oz" - Cast List

"THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ" - CAST LIST PATCHES- Patchwork doll come to life, made from a crazy quilt of fabric. Good physical comedienne. Brutally honest, brave and funny. Any age, 10+. OJO the Unlucky- Actress age 11 to a young looking 20ish female. The Sorceress's hard working Munchkin servant and orphan. Not totally sure of herself yet. But fiercely loyal and determined. Patches' best friend and main focus of the story. MOMBI- Wicked Witch of the North. Glinda's enemy. Devious, sly, dazzling. She has raised Ojo from a baby, and made her into her hardworking serving girl. Practicing forbidden magical arts against Glinda's dictates. LOTTIE LOOKSEE - Mombi's cook who's been like a mother to Ojo Jolly, fun, maternal. (Can double as chorus member). DOROTHY SCARECROW TINMAN GLINDA COWARDLY LION THE NOME KING - The Metal Monarch of the Underworld. Egotistical, funny, throws temper tantrums if he doesn't get his way. Easily bored and amused by tossing stones at people or throwing trespassers down mine shafts. KALIKO - King's long suffering Nome captain. Spends most of his days dodging rocks and staying clear of mine shafts. H.M. WOOGLEBUG - A large bug who fancies himself educated since he lives in a classroom. H.M. stands for Highly Magnified. He was magnified in a microscope and stayed that way. Dresses like an English professor and uses big words. Wears glasses and often has a spare pair perched on his head. POLYCHROME or POLY - The Rainbow's daughter. Appears as a rainbow colored twinkly light half of the time. -

To the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005)

Index to the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005) Adams, Ryan Author "Return to The Marvelous Land of Oz Producer In Search of Dorothy (review): One Hundred Years Later": "Answering Bell" (Music Video): 2005:49:1:32-33 2004:48:3:26-36 2002:46:1:3 Apocrypha Baum, Dr. Henry "Harry" Clay (brother Adventures in Oz (2006) (see Oz apocrypha): 2003:47:1:8-21 of LFB) Collection of Shanower's five graphic Apollo Victoria Theater Photograph: 2002:46:1:6 Oz novels.: 2005:49:2:5 Production of Wicked (September Baum, Lyman Frank Albanian Editions of Oz Books (see 2006): 2005:49:3:4 Astrological chart: 2002:46:2:15 Foreign Editions of Oz Books) "Are You a Good Ruler or a Bad Author Albright, Jane Ruler?": 2004:48:1:24-28 Aunt Jane's Nieces (IWOC Edition "Three Faces of Oz: Interviews" Arlen, Harold 2003) (review): 2003:47:3:27-30 (Robert Sabuda, "Prince of Pop- National Public Radio centennial Carodej Ze Zeme Oz (The ups"): 2002:46:1:18-24 program. Wonderful Wizard of Oz - Czech) Tribute to Fred M. Meyer: "Come Rain or Come Shine" (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 2004:48:3:16 Musical Celebration of Harold Carodejna Zeme Oz (The All Things Oz: 2002:46:2:4 Arlen: 2005:49:1:5 Marvelous Land of Oz - Czech) All Things Oz: The Wonder, Wit, and Arne Nixon Center for Study of (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 Wisdom of The Wizard of Oz Children's Literature (Fresno, CA): Charobnak Iz Oza (The Wizard of (review): 2004:48:1:29-30 2002:46:3:3 Oz - Serbian) (review): Allen, Zachary Ashanti 2005:49:2:33 Convention Report: Chesterton Actress The Complete Life and -

Kid-Friendly*” No Matter What Your Reading Level!

Advanced Readers’ List “Kid-friendly*” no matter what your reading level! *These are suggestions for people who love challenging words and a good story, and want to avoid age-inappropriate situations. Remember though, these books reflect the times when they were written, and sometimes include out-dated attitudes, expressions and even stereotypes. If you wonder, its ok to ask. If you’re bothered, its important to say so. The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein A young boy grows to manhood and old age experiencing the love and generosity of a tree which gives to him without thought of return. Also by Shel Silverstein: Where the Sidewalk Ends: The Poems and Drawings of Shel Silverstein A boy who turns into a TV set and a girl who eats a whale are only two of the characters in a collection of humorous poetry illustrated with the author's own drawings. A Light in the Attic A collection of humorous poems and drawings. Falling Up Another collection of humorous poems and drawings. A Giraffe and a Half A cumulative tale done in rhyme featuring a giraffe unto whom many kinds of funny things happen until he gradually loses them. The Missing Piece A circle has difficulty finding its missing piece but has a good time looking for it. Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook Runny Babbit speaks a topsy-turvy language along with his friends, Toe Jurtle, Skertie Gunk, Rirty Dat, Dungry Hog, and Snerry Jake. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame Emerging from his home at Mole End one spring, Mole's whole world changes when he hooks up with the good-natured, boat-loving Water Rat, the boastful Toad of Toad Hall, the society-hating Badger who lives in the frightening Wild Wood, and countless other mostly well-meaning creatures. -

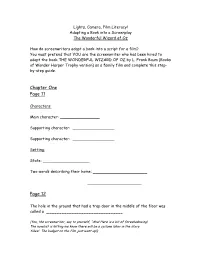

Chapter One Page 11 Page 12

Lights, Camera, Film Literacy! Adapting a Book into a Screenplay The Wonderful Wizard of Oz How do screenwriters adapt a book into a script for a film? You must pretend that YOU are the screenwriter who has been hired to adapt the book THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ by L. Frank Baum (Books of Wonder Harper Trophy version) as a family film and complete this step- by-step guide. Chapter One Page 11 Characters: Main character: ________________ Supporting character: _________________ Supporting character: _________________ Setting: State: ___________________ Two words describing their home: ______________________ ______________________ Page 12 The hole in the ground that had a trap door in the middle of the floor was called a _______________________________ (You, the screenwriter, say to yourself, “Aha! Here is a bit of foreshadowing! The novelist is letting me know there will be a cyclone later in the story. Yikes! The budget on the film just went up!) Pages 13 & 14 - a picture page. Page 15 As Aunt Em has been described on pages 12 & 13, would you write funny lines or serious lines of dialogue for her? _____________________ Based on the novelist’s descriptions of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, who would get more lines of dialogue? _______________________ (“Uh, oh…the director has to work with a dog.”) The story opens with the family worried about ___________________. Pages 16, 17, 18 (“Yep…The cyclone. “) Look at your LCL! 3x3 Story Path Act I. (“Wait,” you say. These steps have hardly been developed at all. In the script, I must add more. I’m not sure what yet, but as I read on, I will look for ideas.”) Chapter Two Pages 19 & 20 - a picture page. -

A Modernized Fairy Tale: Speculations on Technology, Labor, Politics, and Gender in the Oz Series Zachary Hez Hollingsworth University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2018 A Modernized Fairy Tale: Speculations on Technology, Labor, Politics, and Gender in the Oz Series Zachary Hez Hollingsworth University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollingsworth, Zachary Hez, "A Modernized Fairy Tale: Speculations on Technology, Labor, Politics, and Gender in the Oz Series" (2018). Honors Theses. 973. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/973 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “A Modernized Fairy Tale”: Speculations on Technology, Labor, Politics, & Gender in the Oz Series by Zachary Hez Hollingsworth A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2018 Approved by: _______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Jaime Harker _______________________________ Reader: Dr. Daniel A. Novak _______________________________ Reader: Dr. Debra Young © 2018 Zachary Hez Hollingsworth ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Jaime Harker, the one person who was willing and able to help me write this odd little thesis. As I ran around campus being turned down by potential advisor after potential advisor, you were the one name that everyone consistently recommended. And even though we had never properly met prior, you introduced yourself to me as if we had been friends for ages.