Hercules Jewelry Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Combined Metalworking Techniques: Forged Elements and Chased Raised Shapes Bonnie Gallagher

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 1972 Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes Bonnie Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Gallagher, Bonnie, "Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREATISE ON COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES i FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES TREATISE ON. COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES t FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES BONNIE JEANNE GALLAGHER CANDIDATE FOR THE MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN THE COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS OF THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUGUST ( 1972 ADVISOR: HANS CHRISTENSEN t " ^ <bV DEDICATION FORM MUST GIVE FORTH THE SPIRIT FORM IS THE MANNER IN WHICH THE SPIRIT IS EXPRESSED ELIEL SAARINAN IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER, WHO LONGED FOR HIS CHILDREN TO HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO HAVE THE EDUCATION HE NEVER HAD THE FORTUNE TO OBTAIN. vi PREFACE Although the processes of raising, forging, and chasing of metal have been covered in most technical books, to date there is no major source which deals with the functional and aesthetic requirements -

Repoussé Work for Amateurs

rf Bi oN? ^ ^ iTION av op OCT i 3 f943 2 MAY 8 1933 DEC 3 1938 MAY 6 id i 28 dec j o m? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/repoussworkforamOOhasl GROUP OF LEAVES. Repousse Work for Amateurs. : REPOUSSE WORK FOR AMATEURS: BEING THE ART OF ORNAMENTING THIN METAL WITH RAISED FIGURES. tfjLd*- 6 By L. L. HASLOPE. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND, W.C, 1887. PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, STRAND, LONDON. 3W PREFACE. " JjJjtfN these days, when of making books there is no end," ^*^ and every description of work, whether professional or amateur, has a literature of its own, it is strange that scarcely anything should have been written on the fascinating arts of Chasing and Repousse Work. It is true that a few articles have appeared in various periodicals on the subject, but with scarcely an exception they treated only of Working on Wood, and the directions given were generally crude and imperfect. This is the more surprising when we consider how fashionable Repousse Work has become of late years, both here and in America; indeed, in the latter country, "Do you pound brass ? " is said to be a very common question. I have written the following pages in the hope that they might, in some measure, supply a want, and prove of service to my brother amateurs. It has been hinted to me that some of my chapters are rather "advanced;" in other words, that I have gone farther than amateurs are likely to follow me. -

Weights of Various Metals in Pounds Per *Cubic Foot

Weights of Various Metals in Pounds Per *Cubic Foot Aluminum 168.48 Copper 559.87 Manganese 463.10 Silver 654.91 Antimony 419.99 Gold 1206.83 Mercury 849.00 Stainless Steel (18-8) 494.21 Beryllium 113.70 Gun Metal (Aver.) 544.00 Molybdenum 637.63 Steel, Cast/Rolled 490.00 Bismuth 611.00 Iridium 1396.00 Monel Metal 556.00 Tin 455.67 Brass (Approx.) 535.68 Iron 491.09 Nickel 555.72 Titanium 283.39 Bronze, Alum. 481.00 Iron, Cast Grey 442.00 Osmium 1402.00 Tungsten 1204.41 Bronze (Approx.) 541.00 Iron, Wrought 480.00 Palladium 712.00 Vanadium 374.97 Cadmium 540.86 Iron, Slag 172.00 Platinum 1339.20 Zinc 445.30 Chromium 428.00 Lead 707.96 Rhodium 755.00 *1728 CU. IN. PER CU. FT. Cobalt 552.96 Magnesium 108.51 Ruthenium 765.00 Weights of Other Materials in Pounds Per *Cubic Foot Acids, Muriatic, 40% 75.00 Earth, Common Loam 75.00-90.00 Maple, Hard 43.00 Rubber, Goods 94.00 Acids, Nitric, 91% 94.00 Earth, Dry/Loose 76.00 Maple, White 33.00 Sand, Clay & Earth, Dry 100.00 Acids, Sulphuric, 87% 112.00 Earth, Dry/Packed 95.00 Marble 170.00 Sand, Clay & Earth, Wet 120.00 Alcohol, 100% 49.00 Earth, Mud/Packed 115.00 Masonry, Rubble 130.00-150.00 Sand, Pure Quartz, Dry90.00-106.00 Asbestos 153.00 Elm, White 45.00 Masonry, Ashlar 140.00-160.00 Sandstone, Blustone 147.00 Ash, White, Red 40.00 Fats 58.00 Mortar 100.00 Slate 175.00 Asphaltum 81.00 Fir, Douglas 30.00 Mud, River 90.00 Snow, Freshly Fallen 10.00 Basalt 184.00 Fir, Eastern 25.00 Oil, Kerosene 52.00 Snow, Wet 50.00 Brick, Paving 150.00 Flour, Loose 28.00 Oil, Mineral 57.00 Soap Stone, Tall 169.00 Brick, Com. -

Copper Alloys

THE COPPER ADVANTAGE A Guide to Working With Copper and Copper Alloys www.antimicrobialcopper.com CONTENTS I. Introduction ............................. 3 PREFACE Conductivity .....................................4 Strength ..........................................4 The information in this guide includes an overview of the well- Formability ......................................4 known physical, mechanical and chemical properties of copper, Joining ...........................................4 as well as more recent scientific findings that show copper has Corrosion ........................................4 an intrinsic antimicrobial property. Working and finishing Copper is Antimicrobial ....................... 4 techniques, alloy families, coloration and other attributes are addressed, illustrating that copper and its alloys are so Color ..............................................5 adaptable that they can be used in a multitude of applications Copper Alloy Families .......................... 5 in almost every industry, from door handles to electrical circuitry to heat exchangers. II. Physical Properties ..................... 8 Copper’s malleability, machinability and conductivity have Properties ....................................... 8 made it a longtime favorite metal of manufacturers and Electrical & Thermal Conductivity ........... 8 engineers, but it is its antimicrobial property that will extend that popularity into the future. This guide describes that property and illustrates how it can benefit everything from III. Mechanical -

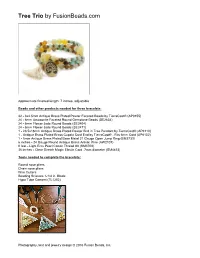

Tree Trio Bracelet Instructions

Tree Trio by FusionBeads.com Approximate finished length: 7 inches, adjustable Beads and other products needed for three bracelets: 32 - 3x4.5mm Antique Brass Plated Pewter Faceted Beads by TierraCast® (AP0155) 24 - 6mm Amazonite Faceted Round Gemstone Beads (SE2634) 24 - 6mm Flower Jade Round Beads (SE2404) 24 - 8mm Flower Jade Round Beads (SE2471) 1 - 26.5x18mm Antique Brass Plated Pewter Bird in Tree Pendant by TierraCast® (AP6110) 1 - Antique Brass Plated Brass Cupola Cord End by TierraCast® - Fits 6mm Cord (AP6102) 1 - 5mm Antique Brass Plated Base Metal 21 Gauge Open Jump Ring (BM2733) 6 inches - 24 Gauge Round Antique Brass Artistic Wire (AW2107) 8 feet - Light Ecru Pearl Cotton Thread #8 (SM3708) 36 inches - Clear Stretch Magic Elastic Cord .7mm diameter (SM4433) Tools needed to complete the bracelets: Round nose pliers Chain nose pliers Wire Cutters Beading Scissors 1-1/4 in. Blade Hypo Tube Cement (TL1202) Photography, text and jewelry design © 2016 Fusion Beads, Inc. Beading Techniques needed to complete the bracelets: Making a Tassel Opening and Closing a Jump Ring Knotting Stretch Magic Wire Wrapping Instructions to complete “Tree Trio” bracelets: Tassel bracelet: Step 1 Wrap the pearl cotton thread around three fingers (see Making a Tassel Technique) until the tassel is as thick as you’d like. Carefully pull the thread loops from your fingers, and trim excess thread. Step 2 Using round nose pliers, make a loop in the middle of a 6-inch length of wire. Photography, text and jewelry design © 2016 Fusion Beads, Inc. Step 3 Wrap the wire around the cord, and make a wire wrapped loop (see Wire Wrapping Technique) with the wire. -

Silver Or Gold: the Color of Brass Instruments in the Late Middle Ages

1 Silver or Gold: The Color of Brass Instruments in the Late Middle Ages Timothy J. McGee The purpose of this article is to lay out some details I have gathered about brass instruments during the late Middle Ages as a way of requesting assistance from the readers of this jour- nal. As will become immediately evident, I am using the word "brass" in its meaning as a synonym for "cup-mouthpiece instruments," because my question has to do with the actual material the instruments were made of. In the process of researching the activities of the civic musicians of Florence during the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries, I have encountered considerable confusion about the material used for trumpets and trombones, and about the symbolism intended by the use of particular metals. Here is what I have found. The earliest reference to the employment of civic musicians in Florence is from gov- ernment documents of 8 February 1292' naming six trumpet players (tubatores) along with a player of the cenamella (probably a double reed) and another who played cimballella (undoubtedly the cymbals). The civic ensemble, known as the trombadori, was part of the ceremonial presence of Florence, participating in all official functions such as the frequent processions welcoming distinguished foreign visitors to the city, civic celebrations in honor of saints' days, or assemblies in which the governing executive appeared in public. The trombadori also accompanied the military in the field, and acted as representatives of the city of Florence by participating in celebrations in other cities. The earliest reference is as follows: .. -

Handbook : Brass, Bronze, Copper, Nickel Silver

•ui#:.r fc ::* £ \ ' TONKt* * i i "t ' 1 .'.'. i HANDBOOK tt BRASS • BRONZE • COPPER NICKEL SILVER I fc Anacon dA from mine to consumer • IftUitilHlli'l J July 1, 1935 3 h * THE AMERICAN BRASS COMPANY 3 * *.. Copyright, 1935 The American Brass Company Printed in U. S. A. C THE AMERICAN BRASS COMPANY General Offices WATERBURY, CONNECTICUT, U.S.A. Manufacturing Plants ANSONIA, CONN. TORRINGTON, CONN. WATERBURY, CONN. BUFFALO, N. Y. DETROIT, MICH. KENOSHA, WIS. Offices and Agencies BOSTON, MASS. 140 Federal Street PROVIDENCE, R. I. 131 Dorrance Strei 1 NEW YORK, N. Y. 25 Broadway SYRACUSE, N. Y. 207 East Genesee Street Place NEWARK, N. J. 20 Branford WASHINGTON, D. C. 1511 K Street, N. W. PHILADELPHIA, PA. 117 South Seventeenth Strei t PITTSBURGH, PA. 535 Smithfield Street CLEVELAND. OHIO 925 Euclid Avenue DAYTON, OHIO 52 North Main Street CINCINNATI, OHIO 101 West Fourth Street CHICAGO, ILL. 1326 West Washington Boulevard ST. LOUIS, MO. 408 Pine Street ATLANTA. GA. 10 Forsyth Street HOUSTON, TEXAS 609 Fannin Street DENVER, COLO. 818 Seventeenth Street LOS ANGELES, CALIF. 411 Weai Fifth Street SAN FRANCISCO, CALIF. 235 Montgomery Street SEATTLE, WASH. 1358 Fourth Avenue THE AMERICAN BRASS COMPANY OF ILLINOIS 1326 West Washington Boulevard, Chicago, 111. In Canada ANACONDA AMERICAN BRASS LIMITED Main Office and Mill NEW TORONTO, ONTARIO Montreal Agency: 1010 St. Catherine Street, W. * 3 CABLE ADDRESSES "AMBRAC" Waterbury, Conn. "AMBRAC" 25 Broadway, New York Codes Used All Standard Cable and Telegraph THE AMERICAN BRASS COMPANY - Tl ANACONDA -

Brass Mill Products

Brass Mill Products Brass Pipe, Rod, Bar, Sheet, Plate, Tubing, and Wire ALASKAN COPPER & BRASS COMPANY www.alaskancopper.com History hen Alaskan Copper W Works was founded as a marine coppersmithing company in 1913, one of its major activities was forming and brazing pipe and pipe fittings made from copper, brass and bronze, primarily for use in the Pacific Northwest shipbuilding industry. Beginning in the 1920’s, many of the area’s growing process industries, such as pulp and paper, which had relied on wood stave and cast iron as corrosion resistant materials for their tanks and piping, welcomed the development of a new weldable alloy, silicon bronze. This alloy had special Alaskan Copper Works yesterday advantages in weight, cost and cor- rosion resistance. Alaskan Copper petrochemical and food processing. elbows began to be made in small Works participated in the transition Again, Alaskan Copper Works par- sizes and gradually advanced to in- to this innovative metal and in the de- ticipated in the application of these clude larger sizes and many radii and velopment of the welding techniques new, advantageous materials and in wall thicknesses. Other advances over necessary for its proper fabrication. the development of the welding and the years have led to tees being made fabricating procedures required to with smooth-drawn outlets, the devel- In the 1930’s, alloys with even bet- maximize their usefulness. opment of many available choices in ter corrosion resistance, such as the the types of stub ends for different austenitic stainless steels, became Over the intervening years, improve- services and our manufacturing of pipe available and quickly came into general ments in our manufacturing capacities and fittings to advanced specifications use not only in the pulp and paper have seen the standard lengths of and in “exotic” alloys, including our industry but also in the other process most pipe sizes increase from 4 feet qualification to produce fittings for industries then beginning to develop, to 10 feet and then to 20 feet. -

Jewellery Lookbook Fw 19/20

JEWELLERY LOOKBOOK FW 19/20 www.katerinavassou.gr TABLE OF CONTENTS Gold plated Collection 33 -- 222125 The Brand 223126 GOLD PLATED JEWELLERY PHOTOGRAPHY OLSI MANE PHOTOGRAPHY MODEL OLSI MANE YPAPANTI VASILA STYLING SISSY PAPATSORI All earring closures are made of 925 Silver. 2 3 CASUALCASUALI COLLECTIONI COLLECTION 4 5 BLACK MOON JOINED OVAL Item Set: Code: Price: Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace 303679 30€ Necklace 303744 21€ Bracelet 303680 29€ Bracelet 303743 24€ Earrings 303678 23€ Earrings 303741 21€ Ring 303738 17€ 6 7 OXI GEOMETRY Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (ropes) 303162 21€ Necklace 303163 21€ Bracelet 303164 21€ Earrings 303165 20€ Ring 303166 15€ 8 9 BLUE MOON OXI ARROW Item Set: Code: Price: Item Set: Code: Price: Earrings 303167 19€ Necklace 303182 28€ Ring 303168 15€ Bracelet 303183 23€ 10 11 SEA ROCK Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace 303180 28€ Bracelet 303181 23€ 12 13 SUMMER CIRCLES MOON & FIRE Item Set: Code: Price: Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (left) 303214 29€ Necklace (right) 302618 26€ Necklace (left) 303214 29€ Necklace (right) 303213 20€ 14 15 PEARL IN “CELL“ SUMMER DISCS Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (wooden spheres) 302669 29€ Bracelet 302670 24€ 18€ Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (large) 302666 Necklace 302665 17€ Necklace (ropes) 303254 13€ Earrings (large) 302668 20€ Necklace 303252 15€ Earrings 302607 18€ Earrings 303253 13€ Ring 302667 15€ 16 17 GEMSTONE FISH SHAPES Item Set: Code: Price: Earrings 303230 15€ Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace 303238 21€ 18 19 AUTUMN TRIANGLES SEA TRIANGLES Item Set: -

Copper Tungsten

REFRACTORY METALS Grade RWMA Type Density Electrical Rockwell Ultimate Cross Break Group B Gm./cc Cond. % Hardness Strength Strength IACS PSI PSI T-1W Class 10 12.6 53 - 60 72 - 82-B 63,000 110,000 T-3W Copper 13.93 48 - 53 85 - 92-B 75,000 130,000 T-5W Tungsten 14.18 46 - 52 88 - 95-B 85,000 140,000 T-10W Class 11 14.8 42 - 50 94 - 100-B 90,000 150,000 T-20W Class 12 15.12 41 - 52 98 - 107-B 95,000 160,000 T-30W 15.6 41 - 49 98 - 106-B 100,000 158,000 T-3W53 * Copper Alloy 13.5 28 - 32 101 - 106-B 120,000 180,000 T-10W53 * Tungsten 14.6 26 - 30 105 - 110-B 160,000 200,000 T-TC5 Copper Tungsten 11.27 42 - 50 90 - 100-B 70,000 140,000 T-TC10 Carbide 11.64 38 - 45 97 - 108-B 75,000 160,000 T-TC20 12.7 27 - 35 34 - 40-C 85,000 180,000 T-TC53 * Copper Alloy 12.6 18 - 23 40 - 50-C 150,000 220,000 Tungsten Carbide T-G12 Silver Tungsten 11.8 50 - 60 50 - 65-B 35,000 65,000 T-G13 Carbide 12.2 45 - 55 70 - 85-B 40,000 90,000 T-G14 13.1 30 - 40 95 - 105-B 55,000 120,000 T-G17 Silver 10.1 45 - 50 80 - 90-B 60,000 135,000 T-G18 Molybdenum 10.2 50 - 55 70 - 80-B 45,000 110,000 T-20S Silver Tungsten 48 - 53 90 - 100-B 70,000 130,000 T-35S 50 - 56 80 - 87-B 50,000 120,000 T-100W Class 13 Tungsten 19.28 31 35 - 50-C 100,000 - T-100M Class 14 Molybdenum 10.2 32 88 - 98-B 100,000 - * Properties listed are those of fully heat treated material. -

Brass & Bronze

The Care and Preservation of Historical Brass and Bronze By Clara Deck, Conservator Revisions by Cuong T. Nguyen, Conservator, The Henry Ford INTRODUCTION Historical brass and bronze can be maintained for years of use and enjoyment provided that some basic care and attention is given to its preservation. The conservation staff at The Henry Ford has compiled the information in this fact sheet to help individuals care for their objects and collections. The first step in the care of collections is to understand and minimize or eliminate conditions that can cause damage. The second step is to follow basic guidelines for care, handling and cleaning. NOTE: This Information Sheet will present a brief overview of the care of brass and bronze objects, stressing appropriate storage and handling as the best means of preservation. It does not address the serious problem of preserving archaeological metals excavated from land or marine sites. People who collect un-conserved archaeological artifacts should be aware that they might be unstable if they do not receive appropriate conservation treatment. It is not within the scope of this document to address all the problems associated with outdoor bronze sculptures. This information sheet may provide some useful information for the care of these objects, but we encourage consultation with a professional conservator on such complicated artifacts. IDENTIFYING BRASS AND BRONZE ARTIFACTS Brass and bronze are alloys of copper. (Two or more metals are combined to form an alloy. Alloys generally have a different appearance or working properties that is dependent on their percent composition.) There are other alloys of copper include gunmetal (red brass), bell metal, and German silver, also called Nickel silver and "paktong". -

Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Metals and Alloys

17 Material Expansion Coefficients Chapter 17 Material Expansion Coefficients Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Metals and Alloys Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Metals and Alloys Table 17-1 provides the linear thermal expansion coefficients of the most frequently used metals and allows. Table 17-1. Linear thermal expansison coefficients of metals and alloys Coefficient of Expansion Alloys ppm/°C ppm/°F ALUMINUM AND ALUMINUM ALLOYS Aluminum (99.996%) 23.6 13.1 Wrought Alloys EC 1060 and 1100 23.6 13.1 2011 and 2014 23.0 12.8 2024 22.8 12.7 2218 22.3 12.4 3003 23.2 12.9 4032 19.4 10.8 5005, 5050, and 5052 23.8 13.3 5056 24.1 13.4 5083 23.4 13.0 5086 23.9 13.3 5154 23.9 13.3 5357 23.7 13.2 5456 23.9 13.3 6061 and 6063 23.4 13.0 6101 and 6151 23.0 12.8 7075 23.2 12.9 7090 and 7178 23.4 13.0 17-2 User’s Manual Chapter 17 Material Expansion Coefficients Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Metals and Alloys Table 17-1. Linear thermal expansison coefficients of metals and alloys (Cont.) Coefficient of Expansion Alloys ppm/°Cppm/°F ALUMINUM AND ALUMINUM ALLOYS (Continued) Casting Alloys A13 20.4 11.4 43 and 108 22.0 12.3 A108 21.5 12.0 A132 19.0 10.6 D132 20.5 11.4 F132 20.7 11.5 138 21.4 11.9 142 22.5 12.5 195 23.0 12.8 B195 22.0 12.3 214 24.0 13.4 220 25.0 13.9 319 21.5 12.0 355 22.0 12.3 356 21.5 12.0 360 21.0 11.7 750 23.1 12.9 40E 24.7 13.8 COPPER AND COPPER ALLOYS Wrought Coppers Pure Copper 16.5 9.2 Electrolytic Tough Pitch Copper (ETP) 16.8 9.4 Deoxidized Copper, High Residual Phosphorous (DHP) 17.7 9.9 Oxygen-Free Copper 17.7 9.9 Free-Machining Copper 0.5% Te or 1% Pb 17.7 9.9 User’s Manual 17-3 Chapter 17 Material Expansion Coefficients Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Metals and Alloys Table 17-1.