Interview with Fernando Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Digital Video: Watch Me Do What I Say!

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 697 IR 021 056 AUTHOR Capraro, Robert M.; Capraro, Mary Margaret; Lamb, Charles E. TITLE Digital Video: Watch Me Do What I Say! PUB DATE 2001-10-00 NOTE 28p.; Paper presented at the Consortium of State Organizations for Texas Teacher Education (Corpus Christi, TX, October 14-16, 2001). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) Tests/Questionnaires (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Technology; Higher Education; Instructional Materials; *Interactive Video; *Lesson Plans; Material Development; *Metacognition; Methods Courses; *Preservice Teacher Education; *Professional Development; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Digital Technology ABSTRACT This paper establishes a use for digital video in developing preservice teacher metacognition about the teaching process using a lesson plan-rating sheet as a guide. A lesson plan was developed to meet the specific needs of the methods instructors in a professional development program at a large public institution. The categories listed on the lesson planning document are: Instructional Objectives; State Objectives; Materials; Background Information; Learning Environment; Focus; Teaching Procedure; Explanation and Practice; Elaboration; Closure; and Assessment. After a semester of using the document, several of the methods instructors believed that preservice teachers were not successfully engaging in lesson planning and not displaying thought processes conducive to cogent, sequential, and organized lesson development. This need precipitated the development of a lesson plan-rating sheet. The lesson plan-rating sheet is based on the original lesson plan form with the addition of indicators. Those indicators are intended to focus the rater's attention on the details of lesson planning and to act as a tool to encourage discourse surrounding effective lesson planning and delivery of instruction in a mathematics methods course. -

January 2020

Abington Senior High School, Abington, PA, 19001 January 2020 Decade in Review! With the decade coming to a close a few weeks ago, the editorial staff decided that we should fl ashback to the ideas and moments that shaped the decade. As we adjust to life in the new “roaring twenties,” here is a breakdown of the most prominent events of each year from the past decade. 2010: On January 12, an earthquake registering a magnitude 7.0 on the Richter scale struck Haiti, causing about 250,000 deaths and 300,000 injuries. On March 23, the Aff ordable Care Act is signed into law by Barack Obama. Commonly referred to as “Obamacare,” it was considered one of the most extensive health care reform acts since Medicare, which was passed in 1965. On April 20, a Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded over the Gulf of Mexico. Killing eleven people, it is considered one of the worst oil spills in history and the largest in US waters. On July 25, Wikileaks, an organization that allows people to anonymously leak classifi ed information, released more than 90,000 documents related to the Afghanistan War. It is oft en referred to as the largest leak of classifi ed information since the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. Th e New Orleans Saints won their fi rst Super Bowl since Hurricane Katrina, LeBron James made his way to Miami, Kobe Bryant won his fi nal title, and Butler went on a Cinderella run to the NCAA Championship. Th e year fi ttingly set the tone for a decade of player empowerment and underdog victories. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

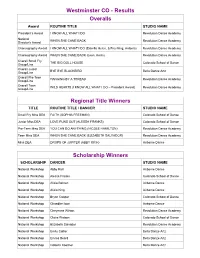

Westminster CO - Results Overalls Award ROUTINE TITLE STUDIO NAME

Westminster CO - Results Overalls Award ROUTINE TITLE STUDIO NAME President’s Award I KNOW ALL WHAT I DO Revolution Dance Academy National WHEN SHE CAME BACK Revolution Dance Academy Director’s Award Choreography Award I KNOW ALL WHAT I DO (Estrella Helen, & Freehling, Antonia) Revolution Dance Academy Choreography Award WHEN SHE CAME BACK (Leon, Kevin) Revolution Dance Academy Overall Small Fry THE BIG DOLL HOUSE Colorado School of Dance Group/Line Overall Junior BYE BYE BLACKBIRD Bella Danze Artz Group/Line Overall Pre-Teen HANGING BY A THREAD Revolution Dance Academy Group/Line Overall Teen WILD HEARTS (I KNOW ALL WHAT I DO – President Award) Revolution Dance Academy Group/Line Regional Title Winners TITLE ROUTINE TITLE / DANCER STUDIO NAME Small Fry Miss DEA FAITH (SOPHIA FREEMAN) Colorado School of Dance Junior Miss DEA LOVE RUNS OUT (ALESSA FRANKS) Colorado School of Dance Pre-Teen Miss DEA YOU CAN DO ANYTHING (NICOLE HAMILTON) Revolution Dance Academy Teen Miss DEA WHEN SHE CAME BACK (ELIZABETH SALVADOR) Revolution Dance Academy Miss DEA DROPS OF JUPITER (ABBY RICH) Airborne Dance Scholarship Winners SCHOLARSHIP DANCER STUDIO NAME National Workshop Abby Rich Airborne Dance National Workshop Alessa Franks Colorado School of Dance National Workshop Alicia Bohren Airborne Dance National Workshop Alicia King Airborne Dance National Workshop Brynn Cooper Colorado School of Dance National Workshop Chandler Isom Airborne Dance National Workshop Cheyenne Wilson Revolution Dance Academy National Workshop Claira Watson Colorado School of -

Myspace.Com - - 43 - Male - PHILAD

MySpace.com - WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM - 43 - Male - PHILAD... http://www.myspace.com/recordcastle Sponsored Links Gear Ink JazznBlues Tees Largest selection of jazz and blues t-shirts available. Over 100 styles www.gearink.com WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM is in your extended "it's an abomination that we are in an network. obama nation ... ron view more paul 2012 ... balance the budget and bring back tube WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Latest Blog Entry [ Subscribe to this Blog ] amps" [View All Blog Entries ] Male 43 years old PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Blurbs United States About me: I have been an avid music collector since I was a kid. I ran a store for 20 years and now trade online. Last Login: 4/24/2009 I BUY PHONOGRAPH RECORDS ( 33 lp albums / 45 rpms / 78s ), COMPACT DISCS, DVD'S, CONCERT MEMORABILIA, VINTAGE POSTERS, BEATLES ITEMS, KISS ITEMS & More Mood: electric View My: Pics | Videos | Playlists Especially seeking Private Pressings / Psychedelic / Rockabilly / Be Bop & Avant Garde Jazz / Punk / Obscure '60s Funk & Soul Records / Original Contacting WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM concert posters 1950's & 1960's era / Original Beatles memorabilia I Offer A Professional Buying Service Of Music Items * LPs 45s 78s CDS DVDS Posters Beatles Etc.. Private Collections ** Industry Contacts ** Estates Large Collections / Warehouse finds ***** PAYMENT IN CASH ***** Over 20 Years experience buying collections MySpace URL: www.myspace.com/recordcastle I pay more for High Quality Collections In Excellent condition Let's Discuss What You May Have For Sale Call Or Email - 717 209 0797 Will Pick Up in Bucks County / Delaware County / Montgomery County / Philadelphia / South Jersey / Lancaster County / Berks County I travel the country for huge collections Print This Page - When You Are Ready To Sell Let Me Make An Offer ----------------------------------------------------------- Who I'd like to meet: WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Friend Space (Top 4) WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM has 57 friends. -

Capital Blues Messenger Capital Blues Messenger

CapitalCapital BluesBlues MessengerMessenger Celebrating the Blues in the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia July 2012 Volume 6 Issue 7 DCBS & Lamont’s Presents Memphis Blues Blowout Saturday, July 21 Photo by Thomas Hawk DCBS Hotter Than July Inside Fish Fry ‘n’ Blues DCBS July Events Saturday, July 14 Aug. 3 Zac Harmon Show and more Blues News & Reviews THE DC BLUES SOCIETY Become a DCBS member! Inside This Issue P.O. BOX 77315 Members are key to the livelihood of the President’s Drum 3 DCBS. Members’ dues play an important DCBS & Lamont’s Presents Memphis WASHINGTON, DC 4 part in helping DCBS fulfill its mission to Blues Blowout 20013-7315 promote the Blues and the musicians who keep the music alive, exciting and accessi- CD Review: Rick Estrin 5 www.dcblues.org DCBS Hotter Than July Fish Fry ‘n ble. Members receive discounts on advance 6 - 7 Blues; Blues Foundation Efforts The DC Blues Society is a non-profit 501(c)(3) sale tickets to DCBS events, DCBS merchan- organization dedicated to keeping the Blues alive dise and from area merchants and clubs Zac Harmon Interview 8 when you present your DCBS membership through outreach and education. The DC Blues Blues Calendar 9 Society is a proud affiliate of the Blues Foundation. card (see p 11). Members also receive the monthly Capital Blues Messenger (CBM) CD Review: Lil’ Ed & Blues Imperials 10 The Capital Blues Messenger is published monthly newsletter and those with e-mail access get DCBS Discounts, Miscelleneous 11 (unless otherwise noted) and sent by e-mail or U.S. -

1. 11 1 I WANT/L SAW HER-Beatles (Cap) 11.1 [U) BABY DON’T WEEP-James Brown (Kin) 2

February 17, 1964 Number Forty Three HIT OF THE WEEK; NAVY BLUE - Diane Renay (20th Fox) A top ten entry in the Carolinas, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Texas, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia. Be sure you’re on it. It’s a heavy weight. CORRESPONDENTS POPULAR PICK; KISSIN' COUSINS/lT HURTS ME - Elvis Presley (RCA) An instant smashI A top seller and request getter in only a week. SURPRISE OF THE WEEK: TO THE AISLE - Jimmy Velvet (ABC) I am not convinced this can do it in the long pull, but it has pulled strong calls where it is programmed. Frank Jolle-WMAK-Nashvllle had one of the first dubs and went with it. A top five request for him. Activity at: WPGA, WTBC, WMOC, KOLE, WROV, WCAW, WNOR, WEKR, KVOL, WMBR, WMNZ, WMTS, WEED and WLBG. HOT ACTION RECORD: SEE THE FUNNY LITTLE CLOWN - Bobby Goldsboro (UA) It keeps building. Sales and/or requests in Tennessee, Texas, though it bombed in Dallas, Georgia, Alabama, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Florida and the Carolinas. SOUTHERN SURVEY CHOICE OF THE WEEK: MY HEART BELONGS TO ONLY YOU - Bobby Vinton (Epic) Hope you've been programming it from the album. Single is due out today. It’ll be another smash for the artist. SOUTHERN TOP TWENTY 1. 11 1 I WANT/l SAW HER-Beatles (Cap) 11. 1[U) BABY DON’T WEEP-James Brown (Kin) 2. 12 1 SHE LOVES YOU-Beatles (Swa) 12. 1l10 FOOL NEVER LEARNS-Andy Williams(Col) 3. <¡4; YOU DON'T OWN ME-Lesley Gore (Mer) 13 . -

Santa Anita Derby

$$750,0001,0000,000 SANTA ANITA HANDICAP SANTA ANITA DERBY GAME ON DUDE Dear Member of the Media: Now in its 78th year of Thoroughbred racing, Santa Anita is proud to have hosted many of the sport’s greatest moments. Although the names of its historic human and horse heroes may have changed in the SANTA ANITA HANDICAP past seven decades of racing, Santa Anita’s prominence in the sport $1,000,000 Guaranteed (Grade I) remains constant. Saturday, March 7, 2015 • Seventy-Eighth Running This year, Santa Anita will present the 78th edition of one of rac- Gross Purse: $1,000,000 Winner’s Share: $600,000 Other Awards: $200,000 second; $120,000 third; $50,000 fourth; $20,000 fifth ing’s premier races — the $1,000,000 Santa Anita Handicap on Saturday, Distance: One and one-quarter miles on the main track March 7. Nominations: Close February 21, 2015 at $100 each The historic Big ‘Cap was the nation’s first continually run $100,000 Supplementary nominations of $25,000 by 12 noon, Feb. 28, 2015 Track and American stakes race and has arguably had more impact on the progress of Dirt Record: 1:57 4/5, Spectacular Bid, 4 (Bill Shoemaker, 126, February 3, Thoroughbred racing than any other single event in the sport. The 1980, Charles H. Strub Stakes) importance of this race and many of its highlights are detailed by the Stakes Record: 1:58 3/5, Affirmed, 4 (Laffit Pincay Jr., 128, March 4, 1979) Gates Open: 10:00 a.m. esteemed sports journalist John Hall beginning on page 2. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

Interview with Corey Washington, Independent Scholar on Jimi Hendrix Seretha D

Williams: Interview with Corey Washington, Independent Scholar on Jimi Hend Interview with Corey Washington, Independent Scholar on Jimi Hendrix Seretha D. Williams (3/6/2019) Most people in Augusta, GA, know Corey Washington. He is a popular history teacher, beloved by his students and their parents. He is a patron of music, attending local cultural events and supporting the burgeoning live music scene in the region. He is an independent author and expert on the life and music of Jimi Hendrix. Having seen him at the Augusta Literary Festival on multiple occasions and purchased one of his books on Hendrix for a friend, I decided to reach out to Mr. Washington for an interview on Hendrix, whom scholars describe as an icon of Afrofutur- ism. 1. How did you first become interested in Jimi Hendrix? I always have to mention the name of a disgraced individual Hulk Hogan, who was later exposed as a racist. But he was the one that hipped me to Hendrix because of his ring entrance music: “Voodoo Child.” The song opened with some weird scratching sounds, which I later learned was Jimi’s pre- cursor to a DJ scratching. He was manipulating the wah-wah pedal to get those sounds from his guitar. That drew me in, and I’ve been collecting his music and researching him ever since. That was in 1996. Follow ups: Washington grew up listening to Disco, House, and Hip-Hop. Born in 1976, Washington identifies a cultural “dead spot” for Hendrix between 1976 and 1990. I asked him why he thought that was.