Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

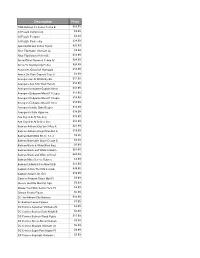

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

Roy Thomas ’Merry Mar vel Comics Fan zine No. 50 July 2005 $ In5th.e9U5SA Sub-Mariner, Thing, Thor, & Vision TM & ©2005 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Conan TM & ©2005 Conan Properties, Inc.; Red Sonja TM & ©2005 Red Sonja Properties, Inc.; Caricature ©2005 Estate of Alfredo Alcala Vol. 3, No. 50 / July 2005 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Roy Thomas Associate Editors Shamelessly Celebrates Bill Schelly 50 Issues of A/E , Vol. 3— Jim Amash & 40 Years Since Design & Layout Christopher Day Modeling With Millie #44! Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Contents Mike Friedrich Production Assistant Writer/Editorial: Make Mine Marvel! . 2 Eric Nolen-Weathington “Roy The Boy” In The Marvel Age Of Comics . 4 Cover Artists Jim Amash interviews Roy Thomas about being Stan Lee’s “left-hand man” Alfredo Alcala, John Buscema, in the 1960s & early ’70s. & Jack Kirby Jerry Ordway DC Comics 196 5––And The Rest Of Roy’s Cover Colorist Color-Splashed Career . Flip Us! Alfredo Alcala (portrait), Tom Ziuko About Our Cover: A kaleidoscopically collaborative combination of And Special Thanks to: three great comic artists Roy worked with and admired in the 1960s and Alfredo Alcala, Jr. Allen Logan ’70s: Alfredo Alcala , John Buscema , and Jack Kirby . The painted Christian Voltan Linda Long caricature by Alfredo was given to him as a birthday gift in 1981 and Alcala Don Mangus showed Rascally Roy as Conan, the Marvel-licensed hero on which the Estelita Alcala Sam Maronie Heidi Amash Mike Mikulovsky two had labored together until 1980, when R.T. -

Tebeografèa Kevin Maguire

TEBEOGRAFÍA KEVIN MAGUIRE Se citan, por orden de fecha de publicación, todas las obras conocidas de Kevin Maguire, cuya participación se destaca en negrita. En las ocasiones en las que Maguire sólo ha realizado una de las historias de la publicación, se menciona el título de ésta y el número de páginas. Siempre que no se haga, se supondrá que corresponde a la historia principal. Editor Serie Núm. / Título de la Portada Guión Lápiz Tinta Año historieta Marvel Hero for Hire 123 Kevin Jim Mark Jerry V- Maguire Owsley Bright Acerno 1986 Marvel Official Handbook of 6 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Joe Ru- V- the Marvel Universe binstein 1986 Deluxe Edition Marvel Official Handbook of 7 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Rubins VI- the Marvel Universe Tein? 1986 Deluxe Edition Marvel Official Handbook of 8 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Rubins VII- the Marvel Universe tein? 1986 Deluxe Edition DC Who is who in the 23 (Tattoed Man, 1 p.) Joe Staton / varios Maguire Dick I- DC Universe?: The Mike Giordano 1987 Definitive Directory DeCarlo DC Who is who in Star 1 (Elasians, 1 p.; Carol Howard Allan Maguire varios III- Trek? Marcus, 1 p.) Chaykin Asherman 1987 DC Who is who in the 25 Maguire / --- --- --- III- DC Universe?: The Dick 1987 Definitive Directory Giordano DC Who is who in Star 2 (Saavik, 1 p.) Howard Allan Maguire Joe Ru- IV- Trek? Chaykin Asherman binstein 1987 DC Justice League 1 (“Born Again”) Maguire / K. Giffen / Maguire Terry V- [Liga de la Justicia #1, Terry Austin J. M. Austin 1987 Zinco, IV-1988] DeMatteis DC Justice League 2 (“Make War No More!”) Maguire / Giffen / Maguire Al Gordon VI- [Liga de la Justicia #2, Al Gordon DeMatteis 1987 Zinco, V-1988] DC Secret Origins 15 (“Death Like a Crown”, Ed Andrew Maguire Dick VI- 15 pp.) [Universo DC Hannigan / Helfer Giordano 1987 #28, Zinco, VI-1991] Giordano DC Focus 1B (portada interior) --- --- Maguire --- VII- 1987 DC Justice League 3 (“Meltdown”) Maguire / Keith Maguire Al Gordon VII- [Liga de la Justicia #3, Al Gordon Giffen / J. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Desert Exposure's

Chihuahua Hill gardens Super New Mexico Picturing the rodeo exposure page 12 page 22 page 28 Biggest Little Paper in the Southwest FREE Our 19th Year! • June 2014 Winner of 4 Top of the Rockies awards from the Society of Professional Journalists! 2 JUNE 2014 www.desertexposure.com www.SmithRealEstate.com Call or Click Today! (575) 538-5373 or 1-800-234-0307 505 W. College Avenue • PO Box 1290 • Silver City, NM 88062 Quality People, Quality Service for over 40 years! Nice 3b/2ba w/ open floor plan, Fixer upper with lots of potential. Borders the Forest! 3b/2ba custom Country living on almost 5ac. vaulted ceilings, & great view. Tile Great investment or sweat equity home on over 9ac with barn & Well maintained Cavco 4b/2ba w/ floors thruout. Lg garage w/ project. Comes with furniture. outbuildings. Saltillo tile, vaulted open floor plan, vaulted ceilings, shelving & workshop space. 2 $59,500. MLS #31156. Call Becky ceilings, custom cabinets & views. wonderful views, outbuildings and storage bldgs included. $229,000. MLS Smith ext. 11. 20 min from town. $279,000. MLS #31007. privacy. $159,500. MLS #31086. Call Becky #30939. Call Becky Smith ext. 11. Call Becky Smith ext. 11. Smith ext 11. Bright open floor plan w/ sun Private, unique location near golf In the pines near Pinos Altos! Spacious 4bdrm, 2-story w/ room, over-sized garage & course. Numerous upgrades Roomy 3b/2.5 ba on almost 2.5 spectacular views! New carpet, forever views! Trex deck, custom including custom cabinets, granite private acres. Large kitchen, new paint, refinished hardwood floors, hickory kitchen cabinets.