Arizona State Board of Nursing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief of Mi Familia Vota, Arizona Center For

Nos.: 19-1257 & 19-1258 In The Supreme Court of the United States MARK BRNOVICH, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ARIZONA, ET AL., Petitioners, – v. – DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, ET AL., Respondents. _________________________ ARIZONA REPUBLICAN PARTY, ET AL., Petitioners, – v. – DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, ET AL., Respondents. _______________________________ ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE MI FAMILIA VOTA, ARIZONA CENTER FOR EMPOWERMENT, CHISPA ARIZONA and LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF ARIZONA IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS JASON A. LECKERMAN ROY HERRERA Counsel of Record DANIEL A. ARELLANO BALLARD SPAHR LLP JILLIAN L. ANDREWS 1735 Market Street, 51st Floor IAN O. BUCON Philadelphia, PA 19103 BALLARD SPAHR LLP (215) 665-8500 1 East Washington Street, [email protected] Suite 2300 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 (602) 798-5400 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .............................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 4 I. Latino Americans’ Right to Vote Is Under Attack ................................................................. 4 A. In Enacting H.B. 2023, the Arizona Legislature Codified Anti-Latino Sentiment ....................................................... 7 B. Arizona’s Legislators Have an Established Record of Anti-Latino Rhetoric ...................... 9 II. The History of the Voting Rights Act Has Been to Include and Protect Latino Voters ..... 10 III. Courts Have Found Attacks on Latino Voters, and § 2 Has Protected These Voters ............... 13 ii IV. The Ninth Circuit Properly Analyzed Arizona’s Voting Policies and Correctly Concluded They Violate the Voting Rights Act ........................... 14 A. Arizona’s Challenged Policies Impose a Disparate Burden on Minority Voters .......................................................... -

Sb-1292-Flyer

Raises the continuing education standards by requiring courses to be relevant to current real estate industry issues and requires real estate educators to take 3 hours of professional workshop. The bill also extends the broker review period from 5 days to 10 business days. SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR What This Victory Means for You... Elevates standards for instructor presentation skills and delivery of instruction to REALTORS®. Helps brokers manage risk by providing a realistic approach to broker review. Members who Supported AAR by Voting for HB 1292 House of Sally Ann Gonzales Carl Seel Adam Driggs Doris Goodale David Burnell Smith Steve Gallardo Representatives David Gowan David Stevens Ron Gould Rick Gray Andy Tobin Linda Gray Kirk Adams Jack Harper Anna Tovar Gail Griffin Lela Alston Matt Heinz Michelle Ugenti Jack Jackson Ben Arredondo Russ Jones Steve Urie Lori Klein Cecil Ash Peggy Judd Ted Vogt Linda Lopez Brenda Barton John Kavanagh Jim Weiers John McComish Judy Burges Debbie Lesko Jerry Weiers Al Melvin Chad Campbell Nancy McLain Vic Williams Robert Meza Heather Carter Javan “J.D.” Mesnard Kimberly Yee Rick Murphy Tom Chabin Eric Meyer John Nelson Chester Crandell Catherin Miranda Russell Pearce Steve Court Richard Miranda Senate Steve Pierce Debbie McCune Davis Steve Montenegro Michele Reagan Jeff Dial Justin Olson Paula Aboud David Schapira Karen Fann Lynne Pancrazi Sylvia Allen Don Shooter Steve Farley Frank Pratt Frank Antenori Kyrsten Sinema Eddie Farnsworth Terri Proud Nancy Barto Steve Smith John Fillmore Amanda Reeve Olivia Cajero Bedford Leah Landrum Taylor Tom Forese Bob Robson Andy Biggs Steve Yarbrough Ruben Gallego Macario Saldate IV Scott Bundgaard. -

Economic Development Committee 2/2/21 Meeting Agenda Packet

SPECIAL NOTICE REGARDING PUBLIC MEETINGS Due to the risks to public health caused by the possible spread of the COVID-19 virus at public gatherings, the Maricopa Association of Governments has determined that public meetings will be indefinitely held through technological means. Meetings will be open to the public through technological means. In reliance on, and compliance with, the March 13, 2020, Opinion issued by Attorney General Mark Brnovich, the Maricopa Association of Governments provides this special advance notice of the technological means through which public meetings may be accessed. While this special notice is in effect, public comment at meetings will only be accepted through written submissions, which may or may not be read aloud during meetings. To attend the meeting noticed below by technological means, members of the public may: 1. To watch a live video stream of the meeting, click here to go to MAG’s YouTube channel. 2. Members of the public may submit written comments relating to this meeting to azmag.gov/comment. Comments may be sent at any time leading up to the meeting, but must be received at least one hour prior to the posted start time for the meeting. If any member of the public has difficulty connecting to the meeting, please contact MAG at (602) 254-6300 for support. January 26, 2021 TO: Members of the MAG Economic Development Committee FROM: Councilmember David Luna, City of Mesa, Chair SUBJECT: MEETING NOTIFICATION AND TRANSMITTAL OF TENTATIVE AGENDA Tuesday, February 2, 2021 – 11:30 a.m. Virtual Meeting The MAG Economic Development Committee meeting has been scheduled at the time noted above. -

Insider's Guidetoazpolitics

olitics e to AZ P Insider’s Guid Political lists ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE ARIZONA CAPITOL TIMES • Arizona Capitol Reports FEATURING PROFILES of Arizona’s legislative & congressional districts, consultants & public policy advocates Statistical Trends The chicken Or the egg? WE’RE EXPERTS AT GETTING POLICY MAKERS TO SEE YOUR SIDE OF THE ISSUE. R&R Partners has a proven track record of using the combined power of lobbying, public relations and advertising experience to change both minds and policy. The political environment is dynamic and it takes a comprehensive approach to reach the right audience at the right time. With more than 50 years of combined experience, we’ve been helping our clients win, regardless of the political landscape. Find out what we can do for you. Call Jim Norton at 602-263-0086 or visit us at www.rrpartners.com. JIM NORTON JEFF GRAY KELSEY LUNDY STUART LUTHER 101 N. FIRST AVE., STE. 2900 Government & Deputy Director Deputy Director Government & Phoenix, AZ 85003 Public Affairs of Client Services of Client Public Affairs Director Development Associate CONTENTS Politics e to AZ ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE Insider’s Guid Political lists STAFF CONTACTS 04 ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE BEATING THE POLITICAL LEGISLATIVE Administration ODDS CONSULTANTS, DISTRICT Vice President & Publisher: ARIZONA CAPITOL TIMES • Arizona Capitol Reports Ginger L. Lamb Arizonans show PUBLIC POLICY PROFILES Business Manager: FEATURING PROFILES of Arizona’s legislative & congressional districts, consultants & public policy advocates they have ‘the juice’ ADVOCATES, -

Municipal 2012

2012 Municipal policy Statement Core Principles • PROTECTION OF SHARED REVENUES. Arizona’s municipalities rely on the existing state-collected shared revenue system to provide quality services to their residents. The League will resist any attacks on this critical source of funding for localities, which are responsibly managing lean budgets during difficult economic times. The League opposes unfunded legislative mandates, as well as the imposition of fees and assessments on municipalities as a means of shifting the costs of State operations onto cities and towns. In particular, the League opposes any further diversions of Highway User Revenue Fund (HURF) monies away from municipalities and calls upon the Legislature to restore diverted HURF funding to critical road and street projects. • PRESERVATION OF LOCAL CONTROL. The League calls upon the Arizona Legislature to respect the authority of cities and towns to govern their communities free from legislative interference and the imposi- tion of regulatory burdens. The League shares the sentiments of Governor Brewer, who, in vetoing anti-city legislation last session, wrote: “I am becoming increasingly concerned that many bills introduced this session micromanage decisions best made at the local level. What happened to the conservative belief that the most effective, responsible and responsive government is government closest to the people?” Fiscal Stewardship The League is prepared to support reasonable reforms to the state revenue system that adhere to the principles of simplicity, fairness and balance and that do not infringe upon the ability of cities and towns to implement tax systems that reflect local priorities and economies. • The League proposes to work with the Legislature to ensure that both the State and municipalities are equipped with the economic development tools they need to help them remain competitive nationally and internationally. -

Animal Defense League of Arizona Met Repeatedly with Bill Sponsor, Rep

2012 LEGISLATIVE REPORT AND SCORECARD Desert Nesting Bald Eagle photo by Robin Silver ARIZONA 2012 LEGISLATIVE REPORT In the 2012 session Arizona legislators passed a bill that will allow law enforcement to seize an animal that is a victim of cruelty or abandonment. However, the legislature also continued its annual attacks on wildlife and citizen initiatives. And for the second year in a row, Senator Ron Gould blocked the bill to expand the roadside sale of animals statewide. The Good Bills Animal Seizure Bill The Legislature passed a bill that allows law enforcement to enter properties to seize an animal if there is probable cause to believe that the animal is suffering from cruelty or abandonment. The bill also requires that those arrested for animal cruelty or fighting, after an appropriate hearing, must post a bond to provide for the cost of caring for seized animals. HB 2462 (Ugenti, Burges*, Carter, Hobbs, Melvin, et al) was requested by law enforcement and supported by animal protection groups. It was signed into law by the governor. *Although Sen. Burges sponsored the bill, she voted against it on the floor. Tucson Greyhound Park ‘Decoupling’ Bill Dog track owners again introduced a bill to reduce the number of live races at Tucson Greyhound Park. SB 1273 (Reagan, Mesnard) passed the legislature and was signed into law by Governor Brewer. The bill was supported by animal protection groups. State law requires dog tracks to run a minimum of nine races a day, for four days a week, in order for the track to conduct simulcasting. -

Download 2014 Summaries As a High Resolution

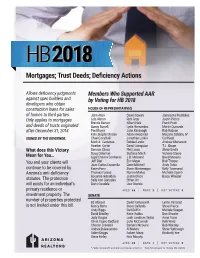

HB2018 Mortgages; Trust Deeds; Deficiency Actions Allows deficiency judgments Members Who Supported AAR against spec builders and by Voting for HB 2018 developers who obtain HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES construction loans for sales of homes to third parties. John Allen David Gowan Jamescita Peshlakai Only applies to mortgages Lela Alston Rick Gray Justin Pierce Brenda Barton Albert Hale Frank Pratt and deeds of trusts originated Sonny Borrelli Lydia Hernandez Martin Quezada after December 31, 2014. Paul Boyer John Kavanagh Bob Robson Kate Brophy McGee Adam Kwasman Macario Saldate, IV SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Chad Campbell Jonathan Larkin Carl Seel Mark A. Cardenas Debbie Lesko Andrew Sherwood Heather Carter David Livingston T.J. Shope What does this Victory Demion Clinco Phil Lovas Steve Smith Doug Coleman Stefanie Mach Victoria Steele Mean for You… Lupe Chavira Contreras J.D. Mesnard David Stevens You and your clients will Jeff Dial Eric Meyer Bob Thorpe Juan Carlos Escamilla Darin Mitchell Andy Tobin continue to be covered by Karen Fann Steve Montenegro Kelly Townsend Arizona’s anti-deficiency Thomas Forese Norma Muñoz Michelle Ugenti Rosanna Gabaldón Justin Olson Bruce Wheeler statutes. The protection Sally Ann Gonzales Ethan Orr will exists for an individual’s Doris Goodale Lisa Otondo primary residence or AYES: 55 | NAYS: 2 | NOT VOTING: 3 investment property. The SENATE number of properties protected Ed Ableser David Farnsworth Lynne Pancrazi is not limited under this bill. Nancy Barto Steve Gallardo Steve Pierce Andy Biggs Gail Griffin Michele Reagan David Bradley Katie Hobbs Don Shooter Judy Burges Leah Landrum Taylor Anna Tovar Olivia Cajero Bedford John McComish Kelli Ward Chester Crandell Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Andrea Dalessandro Al Melvin Steve Yarbrough Adam Driggs Robert Meza Kimberly Yee Steve Farley Rick Murphy AYES: 29 | NAYS: 1 | NOT VOTING: 0 * Eddie Farnsworth and Warren Petersen voted no – they did not want to change the statute. -

Here's the List of Latino Leaders Across Arizona

Here’s the list of Latino leaders across Arizona endorsing Mark Kelly for U.S. Senate: David Adame January Contreras Joseph Garcia Community Leader, Former Department of Advocacy and Education Phoenix Homeland Security Senior Advocate, Phoenix Adviser Gerardo Anaya Marisol Garcia Mayor of Somerton Lupe Contreras Education Leader, State Senator, Tolleson Phoenix Rich Andrade State Representative, Jade Duran Arturo R. Garino Glendale Secretary of the Maricopa Mayor of Nogales Democratic Party Liz Archuleta Sally Ann Gonzales Coconino County Board of Sandra Erunez Otero State Senator, Tucson Supervisors Small Business Owner, Tucson Raúl Grijalva Yolanda Bejarano U.S. Congressman, Labor Leader, Diego Espinoza Tucson Phoenix State Representative, Tolleson Betty Guardado Frank Camacho Vice Mayor / City Council Community Leader, Charlene Fernandez Member, Phoenix Phoenix State Representative, Yuma Lydia Guzman Andrés Cano Community Leader, State Representative, Richard Fimbres Phoenix Tucson City Council Member, Tucson Carmen Heredia Beth Castro Community Leader, Daughter of Former Rosanna Gabaldón Phoenix Governor Raul Castro State Representative, Green Valley Frankie Heredia Alejandro Chavez City Council Member, Community Leader, Steve Gallardo Mesa Phoenix Maricopa County Board of Supervisors Luis Heredia César Chávez Education Leader, State Representative, Ruben Gallego Phoenix Glendale U.S. Congressman, Phoenix Alma Hernandez State Representative, Tucson Consuelo Hernandez Tanairí Ochoa-Martinez Roberto Reveles State Representative, Small -

2020 Election Preview a Pandemic of Electoral Chaos Arizona Association of Health Underwriters Prepared by Dr

2020 Election Preview A Pandemic of Electoral Chaos Arizona Association of Health Underwriters Prepared by Dr. Marcus Osborn and Dan Romm Kutak Rock, LLP Arizona 2020 Key Election Dates Early Register to Request Last Day to Election Day Voting Vote an Early Mail Ballot Begins Deadline Ballot Deadline 2 Arizona 2020 Ballot Propositions “Pot and Schools Go together like Peas and Carrots” 3 Proposition 207 – Smart and Safe Arizona Act Proposition 207 would legalize recreational marijuana use in Arizona for people ages 21 and over. Under the proposal, purchases would be charged the regular sales tax plus an additional 16 percent, which would fund the government’s cost of administering the program. Any money left over will be allocated to community colleges, infrastructure, roads and highways, public safety and public health. This measure allows people who have been arrested or convicted of some marijuana offenses, such as possessing, consuming or transporting 2.5 ounces or less, to petition to have their records expunged. Additionally, this proposal clarifies that people can be charged with driving under the influence of marijuana. 4 Proposition 208 – Invest in Education Act Backed by the state’s teacher’s union, Proposition 208 calls for a 3.5 percent tax surcharge on income above $250,000 for an individual or above $500,000 for couples. This initiative hopes to raise about $940 million a year for schools. Under this ballot proposal, half of the new tax generated would be devoted to raises for credentialed teachers, 25 percent would go to increasing the wages for cafeteria workers, bus drivers and other support staff, and the remaining amount would be allocated for teacher training, vocational education and other initiatives. -

MEMORANDUM Stacy Weltsch Legislative Research Analyst 1700 W

Arizona House of Representatives House Majority Research MEMORANDUM Stacy Weltsch Legislative Research Analyst 1700 W. Washington Committee on Judiciary Phoenix, AZ 85007-2848 (602) 926-3458 FAX (602) 417-3139 To: JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT COMMITTEE Representative Judy Burges, Co-Chair Senator Thayer Verschoor, Co-Chair Re: Arizona Department of Gaming Date: January 6, 2010 Attached is the final report of the sunset review of the Arizona Department of Gaming, which was conducted by the House of Representatives Judiciary and the Senate Judiciary Committee of Reference. This report has been distributed to the following individuals and agencies: Governor of the State of Arizona The Honorable Janice K Brewer President of the Senate Speaker of the House of Representatives Senator Bob Burns Representative Kirk Adams Senate Members House Members Senator John Huppenthal, Co-Chair Representative Cecil Ash, Co-Chair Senator Ken Cheuvront Representative Adam Driggs Senator Chuck Gray Representative Ben Miranda Senator Richard Miranda Representative Steve Montenegro Senator Russell Pearce Representative Anna Tovar Miscellaneous Arizona Department of Gaming Office of the Auditor General Department of Library, Archives & Public Records Office of the Chief Clerk and Secretary of the Senate Senate Democratic Staff House Democratic Staff Senate Republican Staff House Majority Research Staff Senate Research Staff If you have received an electronic copy of this report and would like a hard copy, please contact me. COMMITTEE OF REFERENCE REPORT House of Representatives Committee on Judiciary and Senate Committee on Judiciary ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF GAMING To: JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT COMMITTEE Representative Judy Burges, Co-Chair Senator Thayer Verschoor, Co-Chair Date: January 6, 2010 Pursuant to Title 41, Chapter 27, Arizona Revised Statutes, the Committee of Reference, after performing a sunset review and conducting a public hearing, recommends the following: Tile Arizona Department of Gaming be continued for ten years. -

Notice of a Regular Meeting of the League of Arizona Cities & Towns Executive Committee

NOTICE OF A REGULAR MEETING OF THE LEAGUE OF ARIZONA CITIES & TOWNS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Friday, May 10, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. League Office Building 1820 West Washington, Phoenix Notice is hereby given to the members of the Executive Committee and to the general public that the Executive Committee will hold a meeting open to the public on May 10, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. Members of the Executive Committee will attend either in person or by telephone conference call. The Executive Committee may vote to recess the meeting and move into Executive Session on any item on this agenda. Upon completion of Executive Session, the Executive Committee may resume the meeting, open to the public, to address the remaining items on the agenda. A copy of the agenda is available at the League office building in Suite 200 or on the League website at www.azleague.org. Agenda All items on this agenda are scheduled for discussion and possible action, unless otherwise noted. Call to Order; Pledge of Allegiance 1. Review and Adoption of Minutes 2. Legislative Policy Discussion and Update 3. League Budget for 2019-2020 4. 2019 League Annual Conference Update 5. Report on AMRRP products and services for cities and towns 6. Review and Possible Adoption of League Bylaws Property Corporation Meeting 7. Review and Adoption of Minutes 8. Property Corporation Budget for 2019-2020 9. Annual Election of Officers Executive Session 10. Discussion of Executive Director Ken Strobeck’s Employment Contract 11. Discussion of Executive Recruitment 12. Action on Executive Session matters Additional informational materials are included in the agenda packet but are not part of the agenda. -

ANNUAL CONFERENCECONFERENCE August 20-23 | Jw Marriott Starr PASS T N U C S O

2019 ANNUALANNUAL CONFERENCECONFERENCE aUGUST 20-23 | jw mARRIOTt sTARR PASS T N U C S O Welcome 2 Friday Agenda 18 General Information 3 Spouse/Guest Tour 19 Conference Sponsors 4 Youth Program 20 Tuesday Agenda 6 Service Awards 22 Wednesday Agenda 8 Legislative Awards 2018 23 Thursday Agenda 14 Conference Map 24 WELCOME TO 2019 LEAGUE ANNUAL CONFERENCE As President of the League of Arizona Cities and communities. I look forward to seeing each of you Towns it is my honor to welcome you to the 2019 at this year’s Annual Conference where we will have League Annual Conference. This year's conference the opportunity to share our knowledge, expertise is at the Starr Pass Resort in Tucson, and it promises and friendship with our many colleagues from around to be another stellar experience! Each conference the state. contains a wealth of opportunities to learn from speakers, workshops and each other in order to continue to make our cities and towns amazing places to live. Sincerely, I hope each of you will take advantage of all the conference has to offer, and while at Starr Pass Resort, please make it a point to visit with our sponsors who Christian Price help make this conference such a great event. President, League of Arizona Cities and Towns Mayor, City of Maricopa Over the last year I have personally witnessed your dedication and commitment to your respective 2 LEAGUE LIFE MEMBERS REGISTRATION DESK LOCATION AND HOURS Carol S. Anderson, Kingman • Christopher J. Bavasi, Flagstaff • James L. Boles, Winslow The conference registration desk will be located in the Tucson Ballroom Foyer Douglas Coleman, Apache Junction • Boyd Dunn, Chandler • Stanley M.