Leavenworth to Wellington Field Trip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Featuring Community Events, Local Business Listings, Recreational Opportunities, Outdoor Adventure Information and More

Featuring Community Events, Local business listings, Recreational opportunities, Outdoor adventure information and more. Made possible with grant assistance from The Snohomish County Hotel-Motel tax fund. 923 Main Street, Sultan (360) 217-8174 2 Welcome to the Sky Valley! Located just 45 miles Northeast of Seattle, the Skykomish Valley region boasts many outdoor activities such as kayaking, white water rafting, skiing, hiking, biking, camping, hunting, fishing, and even gold panning to name a few. In recent years the Skykomish River has been recognized as one of the top 5 destination rivers for fishing by national outdoor & sporting magazines. With strong annual Chinook, Coho, Pink and Chum Salmon runs, the rivers can be seen lined with fishermen year round. The Sultan River will come alive with Pink Salmon in the fall of odd number years only. This amazing spectacle of nature is best observed at Sultans’ Osprey Park. Now that the secret is out, the Sky Valley has fast become a haven for fishermen and outdoor adventure seekers from across the region. The Sky Valley is a friendly area that welcomes all adventure seekers. Nestled in the foothills of the picturesque Cascade Mountain Range you can find your own personal adventure. Whether it’s rock climbing or extreme downhill mt. biking or reading by the fire we have what you need to recharge your battery. Established in the late 1880’s, the Sky Valley has a rich and colorful heritage. Logging, mining and agriculture provided the economic and cultural foundation in those early years. Today, we protect the wonderful way of life that our residents have treasured for over one hundred years and welcome new friends. -

Draft Environmental Assessment King County Puget Sound Emergency

United States Draft Department of Environmental Assessment Agriculture Forest Service King County Puget Sound Emergency Radio Network Phase 2 Project February 2018 Puget Sound Emergency Radio Network (PSERN) Skykomish and Snoqualmie Ranger Districts Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest King County, WA For Further Information, Eric Ozog Contact: Verlot Public Service Center (360) 691-4396 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

The Day a Mountain Moved

THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 23, 2012 NY 3 Snow Fall ♦ THE AVALANCHE AT TUNNEL CREEK ♦ The Day A Mountain Moved KEITH CARLSEN chest and neck, the crumbs maddening- The area has all of the alluring qual- After an evening of By JOHN BRANCH ly slid back onto her face. She grew ities of the backcountry — fresh snow, night skiing at claustrophobic. expert terrain and relative solitude — Stevens Pass in Breathe easy, she told herself. Do not but few of the customary inconven- The snow burst through the trees from down. It was not unlike being cart- panic. Help will come. She stared at the iences. Reaching Tunnel Creek from the Cascades in with no warning but a last-second wheeled in a relentlessly crashing low, gray clouds. She had not noticed Stevens Pass ski area requires a ride of Washington on whoosh of sound, a two-story wall of wave. But snow does not recede. It the noise as she hurtled down the moun- just more than five minutes up SkyLine Feb. 18, several of white and Chris Rudolph’s piercing cry: swallows its victims. It does not spit Express, a high-speed four-person tain. Now, she was suddenly struck by those with loose “Avalanche! Elyse!” them out. the silence. chairlift, followed by a shorter ride up The very thing the 16 skiers and Snow filled her mouth. She caromed Seventh Heaven, a steep two-person lift. plans for the next snowboarders had sought — fresh, soft off things she never saw, tumbling Slip through the open boundary gate, day to ski Tunnel snow — instantly became the enemy. -

Summer Newsletter 2018

Summer 2018 ANCIENT SKIERS BIENNIAL BANQUET SET FOR SUNDAY, OCT. 14, 2018 Please come! Our Oct. 14 banquet will be held at the Nile Shrine Golf and Country Club in Mountlake Terrace just north of Seattle. We’ll gather at 5 p.m. and socialize until 6 p.m. (Beer, wine, and cocktails all at reduced prices). Dinner will follow, and the program will be over in time for more socializing. Atop the agenda will be awards for new Hall of Fame inductees Joe Jones, LeRoy Kingland, Laurie Penketh Kaufmann Miller, and Lou Whittaker – all with biographies in our Spring 2018 newsletter. This will be a sit-down dinner (salad, entree, dessert, and coffee or tea) with entree choices shown on the registration form included with this newsletter. Please return the registration form for the banquet to Ancient Skiers, P.O. Box 331, Kirkland, WA 98083, no later than Oct. 6, 2018. A registration form also can be found at: www.ancientskiers.com. Look under “Recent Posts” and follow the stated directions. How to get there: The Nile Shrine Golf & Country Club is at 6601 244th St. SW in Mountlake Terrace, Wash. If traveling from either south or north on the freeway, take Exit 177. Drive west a short distance toward Edmonds on SR 104 (also called NE 205th Street). Stay in the right lane and take the first right driveway/entrance, where there is a Nile sign. Drive the narrow curving road up through the golf course to the large parking area next to the clubhouse. (Don’t bother to look for 244th St., as that will only confuse things for you.) STEVENS PASS BECOMES PART OF THE VAIL SKI RESORT EMPIRE Many Pacific Northwest skiers were surprised in June to will get outpriced, maybe see more big resort-type amenities, and, learn of Vail Resorts’ plans to purchase the Stevens Pass Ski Area. -

2013 Avalanche Hazard Profile

Final Hazard Profile – Avalanche Avalanche Frequency 50+ yrs 10-50 yrs 1-10 yrs Annually People <1,000 1,000-10,000 10,000-50,000 50,000+ Economy 1% GDP 1-2% GDP 2-3% GDP 3%+ GDP Environment <10% 10-15% 15%-20% 20%+ Avalanche Property <$100M $100M-$500M $500M-$1B $1B+ Risk Level Hazard scale < Low to High > Frequency – Avalanches occur annually in Washington. People – National and international statistics show that there is the potential for significant loss of life from an avalanche. Economy – An incident is unlikely to cause the loss of 1% of the State GDP. Environment – An incident is unlikely to cause the loss of 10% of a single species or habitat. Property – An incident is unlikely to cause $100 million in damage. Summary o The hazard – An avalanche occurs when a layer of snow loses its grip on a slope and slides downhill. Avalanches typically occur from November until early summer in all mountain areas, but year-round in high alpine areas. They primarily pose danger to people in areas where there is no avalanche control, and to continued movement of people and freight over the state’s mountain highway passes. o Previous occurrences – Avalanches occur frequently each year and kill one to two people annually in the Northwest (about 25-35 deaths annually in the U.S.). Avalanches have killed more people in Washington than any other hazard during the past century. In 90 percent of avalanche fatalities, the weight of the victim or someone in the victim’s party triggers the slide. -

Stevens Pass Mountain Resort Phase III Projects Environmental Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Stevens Pass Mountain Resort Phase III Projects Environmental Assessment Skykomish Ranger District, Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, King and Chelan Counties, Washington September 2015 For More Information Contact: Forest Supervisor Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest 2930 Wetmore Avenue, Suite 3A Everett, WA 98201 (425) 783-6000 COVER: View of vegetated slopes and bike trails at Stevens Pass. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication for program information (e.g. Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) please contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Skykomish Ranger District, MBS National Forest CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... -

Summits on the Air USA (W7W)

Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7W) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S39.1 Issue number 2.0 Date of issue 01-Dec-2016 Participation start date 01-July-2009 Authorised Date 08-Jul-2009 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Darryl Holman, WW7D, [email protected] Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Summits on the Air – ARM for USA W7W-Washington Table of contents Change Control ................................................................................................................... 4 Disclaimer ........................................................................................................................... 5 Copyright Notices ............................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Association Reference Data .......................................................................................... 6 2.1 Program Derivation ....................................................................................................... 7 2.2 General Information ...................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Final Access, Activation Zone, and Operating Location Explained ............................. 8 2.4 Rights of Way and Access Issues ................................................................................ -

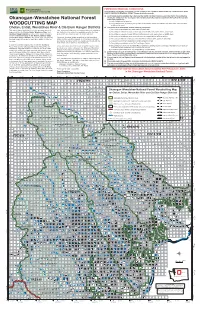

WOODCUTTING MAP a Half Cord of Wood

Forest Service FIREWOOD REMOVAL CONDITIONS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Upon receiving and signing your permit, you are agreeing to the conditions listed on this map and those listed in the FOREST PRODUCTS REMOVAL PERMIT. Please read them carefully. A) Load tickets must be validated (by cutting out the month and date of removal), and attached to the load before moving the vehicle from the cutting site. One validated load ticket must be attached to the back of the load and Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest made clearly visible for: 1) each ½ (half) cord of wood, or 2) any portion thereof. A standard pickup without sideboards, loaded level with the top of the sides, will hold about WOODCUTTING MAP a half cord of wood. Chelan, Entiat, Wenatchee River & Cle Elum Ranger Districts B) This permit is for dead wood, with the following exceptions: 1) No cutting is permitted of any trees within a Timber Sale. This map is being distributed to all who purchase woodcut- Also, some small sites such as campgrounds and administra- ting permits for the Chelan, Entiat, Wenatchee River and tive study sites, are closed to woodcutting within the large 2) No cutting or removal of snags or down logs marked with paint, plastic ribbon, and/or signs. Cle Elum Ranger Districts to show where wood removal is areas which are shown as open to wood collection. 3) No cutting or removal of snags with bird cavities (holes), nests, broken tops, or wildlife signs. allowed. It does not apply to the Naches, Methow Valley 4) No cutting of windthrown green trees without written approval from a Forest Officer. -

Download 1 File

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. Rocky Mountain Forest an&v^ Service )A Forest Range Experiment Station Technical Report RM-8 ieral ^ Forest Service h ! 1975 ch •*w U.S. Department of Agriculture Division oLJf^^fe^f_..._R8search s, Colorado 80521 4 IF / 7 rHE SNOWY rORRENTS: Avalanche Accidents in the Jnited States 1967-71 yKnox Williams Jy Knox Williams Abstract Williams, Knox. 1975. The snowy torrents: Avalanche accidents in the United States 1967-71. USDA For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-8, 190 p. Rocky Mt. For. and Range Exp. Stn., Fort Collins, Colo. 80521. This compilation of 76 avalanche accident reports teaches by example, both good and bad. Commentaries will help those who spend time in the mountains in winter how to avoid getting caught in an avalanche, or if caught, how to survive. Keywords: Avalanche, avalanche rescue. About the cover: A soft-slab avalanche captured at the instant of release. Having triggered the slide, the skier is desperately trying to keep his balance and ski out to the side. Note the intricate pattern of cracks and the buckling of the slab as it fractures into large angular blocks. Photo by R. Ludwig. USDA Forest Service March 1975 General Technical Report RM-8 THE SNOWY TORRENTS: Avalanche Accidents in the United States 1967 - 71 Knox Williams Alpine Snow and Avalanche Project Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station 1 "The snowy torrents are like the deep sea; they seldom return their victims alive." From Kampf iiber die Gletschern (Battle over the Glaciers) by W.