Private Collections. Public Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hidatsa Water Buster (Midi Badi) Clan Negotiates the Return of a Medicine Bundle from the Museum of the American Indian in 1938

arts Article Trusting You Will See This as We Do: The Hidatsa Water Buster (Midi Badi) Clan Negotiates the Return of a Medicine Bundle from the Museum of the American Indian in 1938 Jennifer Shannon Department of Anthropology and Museum of Natural History, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-303-492-6276 Received: 21 August 2019; Accepted: 19 November 2019; Published: 26 November 2019 Abstract: An often cited 1938 repatriation from the Museum of the American Indian in New York City to the members of the Water Buster or Midi Badi clan of the Hidatsa tribe in North Dakota is revisited. Rather than focusing on this event as a “first” in repatriation history or using it as a character assessment of the director of the museum, this account highlights the clan’s agency and resistance through an examination of their negotiation for the return of a sacred bundle and the objects they selected to provide in exchange. Through this example, we see how tribes have had to make hard choices in hard times, and how repatriation is a form of resistance and redress that contributes to the future of a community’s wellbeing in the face of a history of religious and colonial oppression. Keywords: repatriation; cultural patrimony; Native Americans; museums; Hidatsa; Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation; Three Affiliated Tribes; National Museum of the American Indian; Museum of the American Indian; George Gustav Heye Trusting that you will see this in the same light as we do and decide to co-operate with us for the return of the Sacred Bundle. -

Testo Climate Monitoring Solution at the Gilcrease Museum and the Helmerich Center for American Research

Testo Reference Gilcrease Museum Tulsa, Oklahoma Testo Climate Monitoring Solution at the Gilcrease Museum and the Helmerich Center for American Research. Gilcrease Museum Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma specializes in the Thomas Gilcrease had a great affinity for the native American history of the American West with collections of Western culture he experienced as a child. His family moved to live on and Native American art. The museum has a collection of the Creek Nation’s tribal land, and in 1899, as a 9-year-old, he over 350,000 pieces including in excess of 12,000 paintings, was enrolled on the Creek Nation tribal rolls. Thomas Gilcrease drawings and prints plus more than 250,000 archeological gained a great wealth later in life when he discovered oil on his objects. Many art objects are made of organic materials: allotment. He never forgot his childhood and became an avid a Native Chief’s headdress, textiles or Western prints/ collector of Native American artifacts and cultural objects. drawings are very fragile and require a reliable system of His passion was extended to Western art and historical artifacts environmental monitoring to provide a continuous flow of related to the settlement of the West. Thomas Gilcrease started data for further analysis in a specialized software. Testo with storage buildings for his art collections at the present Saveris 2 WiFi temperature and humidity loggers are used museum site and in 1955 transferred his collections to the throughout the Museum and the Helmerich Center for City of Tulsa. Gilcrease Museum is managed by The University American Research to provide environmental records. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 216/Friday, November 6, 2020

71092 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 216 / Friday, November 6, 2020 / Notices Potawatomi Nation (previously listed as DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR institution, or Federal agency that has Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation, control of the Native American human Kansas); Red Cliff Band of Lake National Park Service remains and associated funerary objects. Superior Chippewa Indians of [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0031088; The National Park Service is not Wisconsin; Red Lake Band of Chippewa PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] responsible for the determinations in Indians, Minnesota; Saginaw Chippewa this notice. Indian Tribe of Michigan; Sault Ste. Notice of Inventory Completion: Consultation Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Tennessee Valley Authority, Knoxville, TN A detailed assessment of the human Michigan; Seneca Nation of Indians remains and associated funerary objects (previously listed as Seneca Nation of AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. was made by TVA professional staff in New York); Seneca-Cayuga Nation ACTION: Notice. consultation with representatives of the (previously listed as Seneca-Cayuga Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas Tribe of Oklahoma); Shawnee Tribe; SUMMARY: The Tennessee Valley (previously listed as Alabama-Coushatta Sokaogon Chippewa Community, Authority (TVA) has completed an Tribes of Texas); Cherokee Nation; Wisconsin; St. Croix Chippewa Indians inventory of human remains and Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians; The of Wisconsin; Stockbridge Munsee associated funerary objects in Chickasaw Nation; and The Muscogee Community, -

ENGR. S. C. R. NO. 11 Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

1 ENGROSSED SENATE CONCURRENT 2 RESOLUTION NO. 11 By: Easley, Adelson, Aldridge, Anderson, Ballenger, 3 Barrington, Bass, Bingman, Branan, Brogdon, Brown, 4 Burrage, Coates, Coffee, Corn, Crain, Crutchfield, 5 Eason McIntyre, Ellis, Ford, Garrison, Gumm, 6 Halligan, Ivester, Johnson (Constance), Johnson 7 (Mike), Jolley, Justice, Lamb, Laster, Leftwich, 8 Lerblance, Marlatt, Mazzei, Myers, Newberry, 9 Nichols, Paddack, Reynolds, Rice, Russell, 10 Schulz, Sparks, Stanislawski, Sweeden, 11 Sykes, Wilson and Wyrick of the Senate 12 and 13 Sherrer of the House 14 15 16 17 A Concurrent Resolution recognizing the artistic ability of Willard Stone; encouraging viewing of the 18 Stone exhibit at the Gilcrease Museum; and directing distribution. 19 20 21 WHEREAS, Sculptor Willard Stone was born on February 29, 1916, 22 at Oktaha, near Muskogee, Oklahoma. He was educated in Oktaha 23 public schools. His father died when Willard was an infant, leaving 24 his mother to support the family by working as a sharecropper. As ENGR. S. C. R. NO. 11 Page 1 1 an early teen, he suffered the loss of nearly half of his right hand 2 in an accident and withdrew from school. However, his natural 3 talent as a sculptor prevailed and, at the urging of his friends, 4 Stone entered his works at fairs in Muskogee and Okmulgee. Oklahoma 5 historian Grant Foreman saw Stone’s work and, impressed with his 6 artistic abilities, successfully convinced the young man to enroll 7 at Bacone College; and 8 WHEREAS, Stone stayed at the school from 1936 to 1939 where he 9 was mentored by Acee Blue Eagle and Woodrow Crumbo. -

An Account of the Birth and Growth of Caddo Archeology, As Seen by Review of 50 Caddo Conferences, 1946-2008

Volume 2009 Article 20 2009 An Account of the Birth and Growth of Caddo Archeology, as Seen by Review of 50 Caddo Conferences, 1946-2008 Hester A. Davis Unknown E. Mott Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Davis, Hester A. and Davis, E. Mott (2009) "An Account of the Birth and Growth of Caddo Archeology, as Seen by Review of 50 Caddo Conferences, 1946-2008," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2009, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.21112/.ita.2009.1.20 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2009/iss1/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Account of the Birth and Growth of Caddo Archeology, as Seen by Review of 50 Caddo Conferences, 1946-2008 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2009/iss1/20 An Account of the Birth and Growth of Caddo Archeology, as Seen by Review of 50 Caddo Conferences, 1946-2008 Hester A. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 104/Friday, May 29, 2020/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 104 / Friday, May 29, 2020 / Notices 32415 telephone (602) 534–1572, email Tribe (previously listed as the Yavapai- Native Hawaiian organizations stated in [email protected]. Prescott Tribe of the Yavapai this notice may proceed. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Notice is Reservation, Arizona). DATES: Representatives of any Indian here given in accordance with the Additional Requestors and Disposition Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization Native American Graves Protection and not identified in this notice that wish to Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), 25 U.S.C. Lineal descendants or representatives request transfer of control of these 3005, of the intent to repatriate cultural of any Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian human remains should submit a written items under the control of the Pueblo organization not identified in this notice request with information in support of Grande Museum, Phoenix, AZ, that that wish to claim these cultural items the request to the Department of meet the definition of unassociated should submit a written request with Anthropology, Southern Methodist funerary objects under 25 U.S.C. 3001. information in support of the claim to University at the address in this notice This notice is published as part of the Lindsey Vogel-Teeter, Pueblo Grande by June 29, 2020. National Park Service’s administrative Museum, 4619 E Washington Street, Phoenix, AZ 85034, telephone (602) ADDRESSES: B. Sunday Eiselt, responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 Department of Anthropology, Southern U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in 534–1572, email lindsey.vogel-teeter@ phoenix.gov, by June 29, 2020. After Methodist University, 3225 Daniel this notice are the sole responsibility of Avenue, Heroy Hall #450, Dallas, TX the museum, institution, or Federal that date, if no additional claimants have come forward, transfer of control 75205, telephone (214) 768–2915, email agency that has control of the Native [email protected]. -

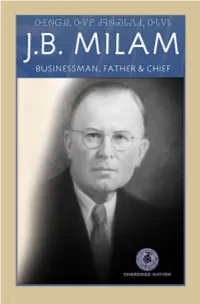

JB Milam Is on the Top Row, Seventh from the Left

Copyright © 2013 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc, PO Box 515, Tahlequah, OK 74465 Design and layout by I. Mickel Yantz All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Businessman,J.B. Father,Milam Chief A YOUNG J. B. MILAM Photo courtesy of Philip Viles Published by Cherokee Heritage Press, 2013 3 J.B. Milam Timeline March 10, 1884 Born in Ellis County, Texas to William Guinn Milam & Sarah Ellen Couch Milam 1887, The Milam family moved to Chelsea, Indian Territory 1898, He started working in Strange’s Grocery Store and Bank of Chelsea 1899, Attended Cherokee Male Seminary May 24, 1902 Graduated from Metropolitan Business College in Dallas, TX 1903, J.B. was enrolled 1/32 degree Cherokee, Cherokee Roll #24953 1904, Drilled his first oil well with Woodley G. Phillips near Alluwe and Chelsea 1904, Married Elizabeth P. McSpadden 1905, Bartley and Elizabeth moved to Nowata, he was a bookkeeper for Barnsdall and Braden April 16, 1907 Son Hinman Stuart Milam born May 10, 1910 Daughter Mildred Elizabeth Milam born 1915 Became president of Bank of Chelsea May 16, 1916 Daughter Mary Ellen Milam born 1933 Governor Ernest W. Marland appointed Milam to the Oklahoma State Banking Board 1936 President of Rogers County Bank at Claremore 1936 Elected President of the Cherokee Seminary Students Association 1937 Elected to the Board of Directors of the Oklahoma Historical Society 1938 Elected permanent chairman for the Cherokees at the Fairfield Convention April 16, 1941 F.D.R. -

Partial Bibliography

Partial Bibliography Part I: (Selected from holdings in the Honey Springs Battlefield Research Collection) Indian Territory Neighboring [& Other] Trans-Mississippi States Slavery; Abolition; African-American Soldiers; &c. Biographies & Memoirs Part II: Relevant articles from the Chronicles of Oklahoma (quarterly journal of the Oklahoma Historical Society) Indian Territory Neighboring [& Other] Trans-Mississippi States Slavery; Abolition; African-American Soldiers; &c. Biographies & Memoirs Indian Territory Able, Annie Heloise; intro. by Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green. The American Indian as Slaveholder and Secessionist. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ABison Books @, 1992; published by the Arthur Clark Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1915; Eicher #678[a].) Abel, Annie Heloise; intro. by Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green. The American Indian in the Civil War, 1862-1865. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ABison Books @, 1992; published by The Arthur H. Clark Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1919; Eicher #678[b].) Able, Annie Heloise; intro. by Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green The American Indian and the End of the Confederacy. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ABison Books @, 1993; published by the Arthur Clark Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1925; Eicher #678[c].) Agnew, Brad. Fort Gibson: Terminal on the Trail of Tears . (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.) Anderson, Mabel Washbourne, with new material by Budd Parrish. Life of General Stand Watie, the only Indian Brigadier General of the Confederate Army and the Last to Surrender. (Harrah, Oklahoma: Brandy Station Bookshelf, 1995, facsimile reprint of 1915 volume by Mayes County Republican, with new maps.) Baird, W. David, and Danny Goble. The Story of Oklahoma. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.) Bartels, Carolyn M. -

The Development of the National Museum of the American Indian Throughout the 1990S

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2020 Woven by the Grandmothers: The Development of the National Museum of the American Indian Throughout the 1990s Lucy Winokur Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Winokur, Lucy, "Woven by the Grandmothers: The Development of the National Museum of the American Indian Throughout the 1990s" (2020). Scripps Senior Theses. 1554. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1554 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOVEN BY THE GRANDMOTHERS: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN THROUGHOUT THE 1990s by LUCY UMLAND WINOKUR SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MICHELLE BERENFELD PROFESSOR JULIA LUM MAY 4, 2020 Acknowledgements While this thesis is the product of my own hard work and passion, I owe endless thanks to my professors, friends, parents, and staff at the NMAI for helping me navigate this thesis, especially during a pandemic. Professor Michelle Berenfeld was my ultimate support system during this process. She challenged my ideas and pushed me one step further every step of the way. -

Heye Foundation Records, 1890-1989

Museum of the American Indian/ Heye Foundation Records, 1890-1989 by Jennifer O'Neal and Rachel Menyuk 2012 This finding aid was generated automatically on August 12, 2014 National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center 4220 Silver Hill Rd Suitland , Maryland, 20746-2863 Phone: 301.238.1400 [email protected] http://nmai.si.edu/explore/collections/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview......................................................................................................... 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 History of the Museum of the American Indian/Heye Foundation................................... 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subject Terms ............................................................................................. 3 Container Listing.............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Directors, 1908-1990................................................................................ 6 Series 2: Board of Trustees, 1916-1990................................................................ 63 Series 3: Administrative, 1916-1989..................................................................... -

ERITAGE Ustainin G

S ustaining Our Heritage The IMLS Achievement ustaining S H Our eritage The IMLS Achievement Dear Colleague, ear Friends, At part of its celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Museum Services I’m delighted to recognize the 25th anniversary of the Act, IMLS is publishing Sustaining Our Heritage: The IMLS Achievement. This is the story of the agency’s long-standing commitment to the Museum Services Act, and the commemoration of that conservation of museum collections. Throughout 17 years of steady and anniversary through the publication of Sustaining Our unwavering support the Institute of Museum and Library Services, in D partnership with American museums, has profoundly improved the care Heritage: the IMLS Achievement. Through the years the of museum collections. These collections tell the epic story of human Institute of Museum and Library Services has been a experience; the legacy of this partnership is that future generations will use and learn from these treasures for years to come. catalyst for excellence and outreach for all Americans. I would like to recognize several individuals whose dedication and Museums of all types, from art and history to science inspiration have been key to this achievement. We are grateful to past directors of the Institute and chairs of the National Museum Services museums and zoos, play an important role in preserving Board, especially Susan Phillips, Lois Burke Sheppard, Peter Raven and our natural and cultural heritage. Many of us remember Willard L. Boyd who were in leadership posts as the conservation focus developed. Much of the credit also goes to the staff of IMLS: Mary the first trips we took to such places. -

Nation-Making and the National Museum of the American Indian

ALL FOR ONE: NATION-MAKING AND THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William Neal Skinner August 2009 © 2009 William Neal Skinner ABSTRACT In September 2004, the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington DC provided the nation with another opportunity to self-narrate on both sub-national and national levels. For many Native and non-Native peoples, the newest Smithsonian Institution represented not only a new method of museological practice based on self-governance and representation but also that Native America existed prior to European Contact, continues today and is worthy of being understood as both part and precursor of a larger collective identity of the nation. This occurred with the museum’s successful Mitsitam Café whereby American cuisine was defined with a Native genesis. The landscape, as well, was scripted as begin original to the northeastern habitat of the United States, in contrast to the Beaux-Arts inspired landscapes of Europe which define the rest of the National Mall. A sensory engagement with both the Café and landscaped grounds, moreover, would separate this particular museal space- intended to be a Native place- from its neighbors. How the senses attend to an engagement with the museum is central to the planning behind the institution- as well as my analysis- whereby the sensorium is mediated both for public consumption and to meeting particular ideological ends. At the same time that Native America is re-presented in our nation’s capital, however, sub-national agendas are continually negotiated by the nation-state, whether aligned or not.