Caribbean Religious History: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Borough of Manhattan Community College 2021 AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture Remi Alapo CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bm_oers/29 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Presented as part of the discussion on West Africa about the instructor’s Heritage in the AFN 121 course History of African Civilizations on April 20, 2021. Yoruba Tradition and Culture Prof. Remi Alapo Department of Ethnic and Race Studies Borough of Manhattan Community College [BMCC]. Questions / Comments: [email protected] AFN 121 - History of African Civilizations (Same as HIS 121) Description This course examines African "civilizations" from early antiquity to the decline of the West African Empire of Songhay. Through readings, lectures, discussions and videos, students will be introduced to the major themes and patterns that characterize the various African settlements, states, and empires of antiquity to the close of the seventeenth century. The course explores the wide range of social and cultural as well as technological and economic change in Africa, and interweaves African agricultural, social, political, cultural, technological, and economic history in relation to developments in the rest of the world, in addition to analyzing factors that influenced daily life such as the lens of ecology, food production, disease, social organization and relationships, culture and spiritual practice. -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar Daniel A

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Doctor of Ministry Theses Student Theses 2002 Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar Daniel A. Rakotojoelinandrasana Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/dmin_theses Part of the Christianity Commons, Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Rakotojoelinandrasana, Daniel A., "Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar" (2002). Doctor of Ministry Theses. 19. http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/dmin_theses/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOLISTIC APPROACH TO MENTAL ILLNESSES AT THE TOBY OF AMBOHIBAO MADAGASCAR by DANIEL A. RAKOTOJOELINANDRASANA A Thesis Submitted to, the Faculty of Luther Seminary And The Minnesota Consortium of Seminary Faculties In Partial Fulfillments of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS ADVISOR: RICHARD WALLA CE. SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA 2002 LUTHER SEMINARY USRARY 22-75Como Aver:ue 1 ©2002 by Daniel Rakotojoelinandrasana All rights reserved 2 Thesis Project Committee Dr. Richard Wallace, Luther Seminary, Thesis Advisor Dr. Craig Moran, Luther Seminary, Reader Dr. J. Michael Byron, St. Paul Seminary, School of Divinity, Reader ABSTRACT The Church is to reclaim its teaching and praxis of the healing ministry at the example of Jesus Christ who preached, taught and healed. Healing is holistic, that is, caring for the whole person, physical, mental, social and spiritual. -

How the Designation of the Steelpan As the National Instrument Heightened Identity Relations in Trinidad and Tobago Daina Nathaniel

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Finding an "Equal" Place: How the Designation of the Steelpan as the National Instrument Heightened Identity Relations in Trinidad and Tobago Daina Nathaniel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION FINDING AN “EQUAL” PLACE: HOW THE DESIGNATION OF THE STEELPAN AS THE NATIONAL INSTRUMENT HEIGHTENED IDENTITY RELATIONS IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By DAINA NATHANIEL A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Daina Nathaniel All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Daina Nathaniel defended on July 20th, 2006. _____________________________ Steve McDowell Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Phil Steinberg Outside Committee Member _____________________________ John Mayo Committee Member _____________________________ Danielle Wiese Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Steve McDowell, Chair, Department of Communication _____________________________________ John Mayo, Dean, College of Communication The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This project is dedicated to the memory of my late father, Danrod Nathaniel, without whose wisdom, love and support in my formative years, this level of achievement would not have been possible. I know that where you are now you can still rejoice in my accomplishments. R.I.P. 01/11/04 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Stand in the space that God has created for you …” It is said that if you do not stand for something, you will fall for anything. -

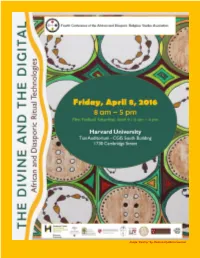

2016 Conference Program

Image “Destiny” by Deanna Oyafemi Lowman MOYO ~ BIENVENIDOS ~ E KAABO ~ AKWABAA BYENVENI ~ BEM VINDOS ~ WELCOME Welcome to the fourth conference of the African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association! ADRSA was conceived during a forum of scholars and scholar- practitioners of African and Diasporic religions held at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School in October 2011 and the idea was solidified during the highly successful Sacred Healing and Wholeness in Africa and the Americas symposium held at Harvard in April 2012. Those present at the forum and the symposium agreed that, as with the other fields with which many of us are affiliated, the expansion of the discipline would be aided by the formation of an association that allows researchers to come together to forge relationships, share their work, and contribute to the growing body of scholarship on these rich traditions. We are proud to be the first US-based association dedicated exclusively to the study of African and Diasporic Religions and we look forward to continuing to build our network throughout the country and the world. Although there has been definite improvement, Indigenous Religions of all varieties are still sorely underrepresented in the academic realms of Religious and Theological Studies. As a scholar- practitioner of such a tradition, I am eager to see that change. As of 2005, there were at least 400 million people practicing Indigenous Religions worldwide, making them the 5th most commonly practiced class of religions. Taken alone, practitioners of African and African Diasporic religions comprise the 8th largest religious grouping in the world, with approximately 100 million practitioners, and the number continues to grow. -

PHD DISSERTATION Shanti Zaid Edit

“A DOG HAS FOUR LEGS BUT WALKS IN ONE DIRECTION:” MULTIPLE RELIGIOUS BELONGING AND ORGANIC AFRICA-INSPIRED RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN ORIENTE CUBA By Shanti Ali Zaid A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology—Dual Major 2019 ABSTRACT “A DOG HAS FOUR LEGS BUT WALKS IN ONE DIRECTION:” MULTIPLE RELIGIOUS BELONGING AND ORGANIC AFRICA-INSPIRED RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN ORIENTE CUBA By Shanti Ali Zaid If religion is about social cohesion and the coordination of meaning, values, and motivations of a community or society, hoW do communities meaningfully navigate the religious domain in an environment of multiple religious possibilities? Within the range of socio-cultural responses to such conditions, this dissertation empirically explores “multiple religious belonging,” a concept referring to individuals or groups Whose religious identity, commitments, or activities may extend beyond a single coherent religious tradition. The project evaluates expressions of this phenomenon in the eastern Cuban city of Santiago de Cuba With focused attention on practitioners of Regla Ocha/Ifá, Palo Monte, Espiritismo Cruzado, and Muertería, four organic religious traditions historically evolved from the efforts of African descendants on the island. With concern for identifying patterns, limits, and variety of expression of multiple religious belonging, I employed qualitative research methods to explore hoW distinctions and relationships between religious traditions are articulated, navigated, and practiced. These methods included directed formal and informal personal intervieWs and participant observations of ritual spaces, events, and community gatherings in the four traditions. I demonstrate that religious practitioners in Santiago manage diverse religious options through multiple religious belonging and that practitioners have strategies for expressing their multiple religious belonging. -

Trinidad and Tobago 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of conscience and religious belief and practice, including worship. It prohibits discrimination based on religion. Laws prohibit actions that incite religious hatred and violence. In June the parliament unanimously passed legislation outlawing childhood marriage, which changed the legal marriage age for all regardless of religious affiliation to 18. The president proclaimed the legislation in September. Religious organizations had mixed reactions to the new law. The Hindu Women’s Organization of Trinidad and Tobago, the National Muslim Women’s Organization of Trinidad and Tobago, and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) supported the legislation, while some religious organizations, including the leader of an orthodox Hindu organization (Sanatan Dharma Maha Saba) said it would infringe on religious rights. Religious groups said the government continued its financial support for religious ceremonies and for the Inter-Religious Organization (IRO), an interfaith coordinating committee. The government’s national security policy continued to limit the number of long-term foreign missionaries to 35 per registered religious group at any given time. The government-funded IRO, representing diverse denominations within Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and the Bahai Faith, continued to advocate for matters of religious concern and the importance of religious tolerance. With a mandate “to speak to the nation on matters of social, moral, and spiritual concern,” the IRO focused its efforts on marches, press conferences, and statements regarding tolerance for religious diversity and related issues. U.S. embassy representatives met with senior government officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to discuss the importance of government protection of religious equality. -

Religion and the Alter-Nationalist Politics of Diaspora in an Era of Postcolonial Multiculturalism

RELIGION AND THE ALTER-NATIONALIST POLITICS OF DIASPORA IN AN ERA OF POSTCOLONIAL MULTICULTURALISM (chapter six) “There can be no Mother India … no Mother Africa … no Mother England … no Mother China … and no Mother Syria or Mother Lebanon. A nation, like an individual, can have only one Mother. The only Mother we recognize is Mother Trinidad and Tobago, and Mother cannot discriminate between her children. All must be equal in her eyes. And no possible interference can be tolerated by any country outside in our family relations and domestic quarrels, no matter what it has contributed and when to the population that is today the people of Trinidad and Tobago.” - Dr. Eric Williams (1962), in his Conclusion to The History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, published in conjunction with National Independence in 1962 “Many in the society, fearful of taking the logical step of seeking to create a culture out of the best of our ancestral cultures, have advocated rather that we forget that ancestral root and create something entirely new. But that is impossible since we all came here firmly rooted in the cultures from which we derive. And to simply say that there must be no Mother India or no Mother Africa is to show a sad lack of understanding of what cultural evolution is all about.” - Dr. Brinsley Samaroo (Express Newspaper, 18 October 1987), in the wake of victory of the National Alliance for Reconstruction in December 1986, after thirty years of governance by the People’s National Movement of Eric Williams Having documented and analyzed the maritime colonial transfer and “glocal” transculturation of subaltern African and Hindu spiritisms in the southern Caribbean (see Robertson 1995 on “glocalization”), this chapter now turns to the question of why each tradition has undergone an inverse political trajectory in the postcolonial era. -

Haiti and the United States During the 1980S and 1990S: Refugees, Immigration, and Foreign Policy

Haiti and the United States During the 1980s and 1990s: Refugees, Immigration, and Foreign Policy Carlos Ortiz Miranda* I. INTRODUCTION The Caribbean nation of Haiti is located on the western third of the island of Hispaniola, and shares that island with the Dominican Republic. To its northwest lies the Windward Passage, a strip of water that separates Haiti from the island of Cuba by approximately fifty miles. 1 Throughout the 1980s and 1990s the Windward Passage has been used as the maritime route of choice by boatpeople fleeing Haiti for political reasons or seeking greater economic opportunity abroad.2 * Assistant General Counsel, United States Catholic Conference. B.A. 1976, University of Puerto Rico; J.D. 1980, Antioch School ofLaw; LL.M. 1983, Georgetown University Law Center. Adjunct Professor, Columbus School of Law, Catholic University of America. The views expressed in this Article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views his employer, nor the Columbus School of Law. I. See CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, THE WORLD FACTBOOK 1993 167-69 (1994). See generally FEDERAL RESEARCH DIVISION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, DoMINICAN REPUBLIC AND HAITI: COUNTRY STUDIES 243-373 (Richard A. Haggerty ed., 1991) [hereinafter COUNTRY STUDIES]. 2. Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. See COUNTRY STUDIES, supra note 1, at 881. There is no question that poverty is widespread, but poverty is not the only reason why people have fled the island throughout the 1980s and 1990s. See Robert D. Novak, Collison Course on Haiti, WASH. POST, May 2, 1994, at Al9 (explaining that the Clinton administration is taking a harder line against "[t]he military rulers that will expand the flow of refugees, who are fleeing economic 673 Haiti was one of the first nations in the Americas to obtain indepen dence. -

Orisha Journeys: the Role of Travel in the Birth of Yorùbá-Atlantic Religions 1

Arch. de Sc. soc. des Rel., 2002, 117 (janvier-mars) 17-36 Peter F. COHEN ORISHA JOURNEYS: THE ROLE OF TRAVEL IN THE BIRTH OF YORÙBÁ-ATLANTIC RELIGIONS 1 Introduction 2 In recent years the array of Orisha 3 traditions associated withtheYorùbá- speaking peoples of West Africa has largely broken free of the category of “Afri- can traditional religion” and begun to gain recognition as a nascent world religion in its own right. While Orisha religions are today both trans-national and pan-eth- nic, they are nonetheless the historical precipitate of the actions and interactions of particular individuals. At their human epicenter are the hundreds of thousands of Yorùbá-speaking people who left their country during the first half of the 19th cen- tury in one of the most brutal processes of insertion into the world economy under- gone by any people anywhere; the Atlantic slave trade. While the journey of the Middle Passage is well known, other journeys under- taken freely by Africans during the period of the slave trade – in a variety of direc- tions, for a multiplicity of reasons, often at great expense, and sometimes at great personal risk – are less so. These voyages culminated in a veritable transmigration involving thousands of Yorùbá-speaking people and several points on both sides of 1 Paper presented at the 1999 meeting of the Société Internationale de la Sociologie des Religions. This article was originally prepared in 1999. Since then, an impressive amount of literature has been published on the subject, which only serves to strengthen our case. A great deal of new of theoretical work on the African Diaspora in terms of trans-national networks and mutual exchanges has not so much challenged our arguments as diminished their novelty. -

Being Muslim: a Cultural History of Women of Chicago in the 1990S, Castor Takes the Reader on a Color in American Islam

congresses and the incorporation of Orishas into national politics, Black Power and African con- Trinidadian carnival (including the tensions it sciousness for shaping what became (and what con- caused within Ifa/Orisha communities) to highlight tinues to become) Ifa/Orisha religion as practiced differences between what Castor calls Yoruba-cen- in Trinidad. In this, we learn how specific local con- tric shrines (religious communities that look to texts, international connections and particular trav- Africa for spiritual authority and ritual guidance) elers shaped and continue to mold this diasporic and Trinidad-centric shrines (communities rooted African-based religion in Trinidad, placing Castor’s in local practices and histories in Trinidad). Chap- ethnography alongside recent work of scholars of ter 4 explores the growing transnational networks Yorub a religion in places like South Carolina of practitioners by focusing on connections (Clarke 2004) and Cuba (Beliso-De Jesus 2015). between the Caribbean and Africa, especially This highly recommended ethnography would be a through the experiences of many who traveled to very valuable text for undergraduate and graduate Nigeria for participation in the Seventh annual students, general scholars and practitioners alike. Orisha World Congress in Nigeria in 2001. Here, Castor investigates how people were initiated in REFERENCES CITED Nigeria and what she calls spiritual economies: Beliso-De Jesus, Aisha. 2015. Electric Santeria: Racial and Sexual “the transfer and exchange of value...for spiritual Assemblages of Transnational Religion, New York: Columbia labor” (p. 122). Chapter 5 explores how the first University Press. Clarke, Kamari. 2004. Mapping Yoruba Networks: Power and Ifa divinatory lineages were established in Trini- Agency in the Making of Transnational Communities. -

Syncretism, Revitalization and Conversion

RELIGIOUS SYNTHESIS AND CHANGE IN THE NEW WORLD: SYNCRETISM, REVITALIZATION AND CONVERSION by Stephen L. Selka, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Schmidt College of Arts and Humanities in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 1997 ABSTRACT Author: Stephen L. Selka. Jr. Title: Religious Synthesis and Change in the New World: Syncretism, Revitalization and Conversion Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Gerald Weiss, Ph.D. Degree: Master of Arts Year: 1997 Cases of syncretism from the New World and other areas, with a concentration on Latin America and the Caribbean, are reviewed in order to investigate the hypothesis that structural and symbolic homologies between interacting religions are preconditions for religious syncretism. In addition, definitions and models of, as well as frameworks for, syncretism are discussed in light of the ethnographic evidence. Syncretism is also discussed with respect to both revitalization movements and the recent rise of conversion to Protestantism in Latin America and the Caribbean. The discussion of syncretism and other kinds of religious change is related to va~ious theoretical perspectives, particularly those concerning the relationship of cosmologies to the existential conditions of social life and the connection between religion and world view, attitudes, and norms. 11 RELIGIOUS SYNTHESIS AND CHANGE lN THE NEW WORLD: SYNCRETISM. REVITALIZATION AND CONVERSION by Stephen L. Selka. Jr. This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor. Dr. Gerald Weiss. Department of Anthropology, and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee.