Barcoding the Asteraceae of Tennessee, Tribe Coreopsideae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

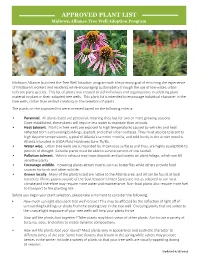

APPROVED PLANT LIST Midtown Alliance Tree Well Adoption Program

APPROVED PLANT LIST Midtown Alliance Tree Well Adoption Program Midtown Alliance launched the Tree Well Adoption program with the primary goal of enriching the experience of Midtown’s workers and residents while encouraging sustainability through the use of low-water, urban tolerant plant species. This list of plants was created to aid individuals and organizations in selecting plant material to plant in their adopted tree wells. This plant list is intended to encourage individual character in the tree wells, rather than restrict creativity in the selection of plants. The plants on the approved list were selected based on the following criteria: • Perennial. All plants listed are perennial, meaning they last for two or more growing seasons. Once established, these plants will require less water to maintain than annuals. • Heat tolerant. Plants in tree wells are exposed to high temperatures caused by vehicles and heat reflected from surrounding buildings, asphalt, and other urban surfaces. They must also be tolerant to high daytime temperatures, typical of Atlanta’s summer months, and cold hardy in the winter months. Atlanta is located in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7b/8a. • Water wise. Urban tree wells are surrounded by impervious surfaces and thus, are highly susceptible to periods of drought. Suitable plants must be able to survive periods of low rainfall. • Pollution tolerant. Vehicle exhaust may leave deposits and pollutants on plant foliage, which can kill sensitive plants. • Encourage wildlife. Flowering plants attract insects such as butterflies while others provide food sources for birds and other wildlife. • Grown locally. Many of the plants listed are native to the Atlanta area, and all can be found at local nurseries. -

Prospects for Biological Control of Ambrosia Artemisiifolia in Europe: Learning from the Past

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2011.00879.x Prospects for biological control of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in Europe: learning from the past EGERBER*,USCHAFFNER*,AGASSMANN*,HLHINZ*,MSEIER & HMU¨ LLER-SCHA¨ RERà *CABI Europe-Switzerland, Dele´mont, Switzerland, CABI Europe-UK, Egham, Surrey, UK, and àDepartment of Biology, Unit of Ecology & Evolution, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland Received 18 November 2010 Revised version accepted 16 June 2011 Subject Editor: Paul Hatcher, Reading, UK management approach. Two fungal pathogens have Summary been reported to adversely impact A. artemisiifolia in the The recent invasion by Ambrosia artemisiifolia (common introduced range, but their biology makes them unsuit- ragweed) has, like no other plant, raised the awareness able for mass production and application as a myco- of invasive plants in Europe. The main concerns herbicide. In the native range of A. artemisiifolia, on the regarding this plant are that it produces a large amount other hand, a number of herbivores and pathogens of highly allergenic pollen that causes high rates of associated with this plant have a very narrow host range sensitisation among humans, but also A. artemisiifolia is and reduce pollen and seed production, the stage most increasingly becoming a major weed in agriculture. sensitive for long-term population management of this Recently, chemical and mechanical control methods winter annual. We discuss and propose a prioritisation have been developed and partially implemented in of these biological control candidates for a classical or Europe, but sustainable control strategies to mitigate inundative biological control approach against its spread into areas not yet invaded and to reduce its A. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Coreopsideae Daniel J

Chapter42 Coreopsideae Daniel J. Crawford, Mes! n Tadesse, Mark E. Mort, "ebecca T. Kimball and Christopher P. "andle HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND PHYLOGENY In a cladistic analysis of morphological features of Heliantheae by Karis (1993), Coreopsidinae were reported Morphological data to be an ingroup within Heliantheae s.l. The group was A synthesis and analysis of the systematic information on represented in the analysis by Isostigma, Chrysanthellum, tribe Heliantheae was provided by Stuessy (1977a) with Cosmos, and Coreopsis. In a subsequent paper (Karis and indications of “three main evolutionary lines” within "yding 1994), the treatment of Coreopsidinae was the the tribe. He recognized ! fteen subtribes and, of these, same as the one provided above except for the follow- Coreopsidinae along with Fitchiinae, are considered ing: Diodontium, which was placed in synonymy with as constituting the third and smallest natural grouping Glossocardia by "obinson (1981), was reinstated following within the tribe. Coreopsidinae, including 31 genera, the work of Veldkamp and Kre# er (1991), who also rele- were divided into seven informal groups. Turner and gated Glossogyne and Guerreroia as synonyms of Glossocardia, Powell (1977), in the same work, proposed the new tribe but raised Glossogyne sect. Trionicinia to generic rank; Coreopsideae Turner & Powell but did not describe it. Eryngiophyllum was placed as a synonym of Chrysanthellum Their basis for the new tribe appears to be ! nding a suit- following the work of Turner (1988); Fitchia, which was able place for subtribe Jaumeinae. They suggested that the placed in Fitchiinae by "obinson (1981), was returned previously recognized genera of Jaumeinae ( Jaumea and to Coreopsidinae; Guardiola was left as an unassigned Venegasia) could be related to Coreopsidinae or to some Heliantheae; Guizotia and Staurochlamys were placed in members of Senecioneae. -

Sfblake and Tithonia Diversifolia

Prospective agents for the biological control of Tithonia rotundifolia (Mill.) S.F.Blake and Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A.Gray (Asteraceae) in South Africa D.O. Simelane1*, K.V. Mawela1 & A. Fourie2 1Agricultural Research Council-Plant Protection Research Institute, Private Bag X134, Queenswood, 0121 South Africa 2Agricultural Research Council-Plant Protection Research Institute, Private Bag X5017 Stellenbosch, 7599 South Africa Starting in 2007, two weedy sunflower species, Tithonia rotundifolia (Mill.) S.F.Blake and Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A.Gray (Asteraceae: Heliantheae), were targeted for biological control in South Africa. Surveys conducted in their native range (Mexico) revealed that there were five potential biological control agents for T.rotundifolia, and three of these are currently undergoing host-specificity and performance evaluations in South Africa. Two leaf-feeding beetles, Zygogramma signatipennis (Stål) and Zygogramma piceicollis (Stål) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), are the most promising biological control agents for T. rotundifolia: prelimi- nary host-specificity trials suggest that they are adequately host-specific. The stem-boring beetle, Lixus fimbriolatus Boheman (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), is also highly damaging to T. rotundifolia, but its host range is yet to be determined. Two other stem-boring beetles, Canidia mexicana Thomson (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and Rhodobaenus auctus Chevrolat (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), have also been recorded on T. rotundifolia, and these will be considered for further testing if L. fimbriolatus is found to be unsuitable for release in South Africa. Only two insect species were imported as candidate agents on T. diversifolia, the leaf-feeding butterfly Chlosyne sp. (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), and an unidentified stem-boring moth (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae): the latter was tested in quarantine but rejected because it attacked several sunflower cultivars. -

Aberrant Plant Diversity in the Purgatory Watershed of Southeastern Colorado and Northeastern New Mexico

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 3 Article 6 10-3-2017 Aberrant plant diversity in the Purgatory Watershed of southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico Joseph A. Kleinkopf University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, [email protected] Dina A. Clark University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, [email protected] Erin A. Tripp University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Kleinkopf, Joseph A.; Clark, Dina A.; and Tripp, Erin A. (2017) "Aberrant plant diversity in the Purgatory Watershed of southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(3), © 2017, pp. 343–354 ABERRANT PLANT DIVERSITY IN THE PURGATORY WATERSHED OF SOUTHEASTERN COLORADO AND NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO Joseph A. Kleinkopf1,2,3, Dina A. Clark2, and Erin A. Tripp1,2,4 ABSTRACT.—Despite a dearth of biological study in the area, the Purgatory Watershed concentrated in southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico is home to a number of unique land formations and endemic organisms. At onetime nonarable land where Dust Bowl storms of the 1930s originated, the Purgatory Watershed is presently home to the Comanche National Grasslands, the Picketwire Canyonlands, and the expansive Piñon Canyon Maneuver Site. -

Mise En Page 1

Systematic revision of the genus Isostigma Less. (Asteraceae, Coreopsideae) Guadalupe Peter Abstract Résumé PETER, G. (2009). Systematic revision of the genus Isostigma Less. (Aster- PETER, G. (2009). Révision systématique du genre Isostigma Less. (Aster- aceae, Coreopsideae). Candollea 64: 5-30. In English, English and French aceae, Coreopsideae). Candollea 64: 5-30. En anglais, résumés anglais et abstracts. français. Isostigma Less. (Asteraceae, Coreopsideae) is a South Ameri- Isostigma Less. (Asteraceae, Coreopsideae) est un genre sud- can genus, distributed in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, américain, distribué en Argentine, au Brésil, en Bolivie, au and Uruguay. This genus has 2 subgenus (Isostigma Less. and Paraguay et en Uruguay. Ce genre comprend 2 sous-genres Microtrichon Guad. Peter) including 11 species (Isostigma acaule (Isostigma Less. et Microtrichon Guad. Peter) incluant 11 (Baker) Chodat, Isostigma brasiliense (Gardner) B. D. Jacks., espèces (Isostigma acaule (Baker) Chodat, Isostigma brasi- Isostigma cordobense Cabrera, Isostigma dissitifolium Baker, liense (Gardner) B. D. Jacks., Isostigma cordobense Cabrera, Isostigma herzogii Hassl., Isostigma hoffmannii Kuntze, Iso - Isostigma dissitifolium Baker, Isostigma herzogii Hassl., stigma molfinianum Sherff, Isostigma peucedanifolium (Spreng.) Isostigma hoffmannii Kuntze, Isostigma molfinianum Sherff, Less., Isostigma scorzonerifolium (Baker) Sherff, Isostigma sim- Isostigma peucedanifolium (Spreng.) Less., Isostigma scorzo- plicifolium Less. and Isostigma sparsifolium Guad. Peter) and nerifolium (Baker) Sherff, Isostigma simplicifolium Less. et 6 varieties. Here are described the new subgenus Microtrichon Isostigma sparsifolium Guad. Peter) et 6 variétés. Ici sont and the taxon Isostigma peucedanifolium var. strictum Guad. décrits le nouveau sous-genre Microtrichon et le taxon Peter. Three new status and combinations are made: Isostigma Isostigma peucedanifolium var. strictum Guad. Peter. Trois peucedanifolium var. -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM LIST OF THE RARE PLANTS OF NORTH CAROLINA 2012 Edition Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist and John Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org Table of Contents LIST FORMAT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 NORTH CAROLINA RARE PLANT LIST ......................................................................................................................... 10 NORTH CAROLINA PLANT WATCH LIST ..................................................................................................................... 71 Watch Category -

New Insights on Bidens Herzogii (Coreopsideae, Asteraceae), an Endemic Species from the Cerrado Biogeographic Province in Bolivia

Ecología en Bolivia 52(1): 21-32. Mayo 2017. ISSN 1605-2528. New insights on Bidens herzogii (Coreopsideae, Asteraceae), an endemic species from the Cerrado biogeographic province in Bolivia Novedades en el conocimiento de Bidens herzogii (Coreopsideae, Asteraceae), una especie endémica de la provincia biogeográfica del Cerrado en Bolivia Arturo Castro-Castro1, Georgina Vargas-Amado2, José J. Castañeda-Nava3, Mollie Harker1, Fernando Santacruz-Ruvalcaba3 & Aarón Rodríguez2,* 1 Cátedras CONACYT – Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional, Unidad Durango (CIIDIR-Durango), Instituto Politécnico Nacional. 2 Herbario Luz María Villarreal de Puga (IBUG), Instituto de Botánica, Departamento de Botánica y Zoología, Universidad de Guadalajara. Apartado postal 1-139, Zapopan 45101, Jalisco, México. *Author for correspondence: [email protected] 3 Laboratorio de Cultivo de Tejidos, Departamento de Producción Agrícola, Universidad de Guadalajara. Apartado postal 1-139, Zapopan 45101, Jalisco, México. Abstract The morphological limits among some Coreopsideae genera in the Asteraceae family are complex. An example is Bidens herzogii, a taxon first described as a member of the genus Cosmos, but recently transferred to Bidens. The species is endemic to Eastern Bolivia and it grows on the Cerrado biogeographic province. Recently collected specimens, analysis of herbarium specimens, and revisions of literature lead us to propose new data on morphological description and a chromosome counts for the species, a tetraploid, where x = 12, 2n = 48. Lastly, we provide data on geographic distribution and niche modeling of B. herzogii to predict areas of endemism in Eastern Bolivia. This area is already known for this pattern of endemism, and the evidence generated can be used to direct conservation efforts. -

Ndhf Sequence Evolution and the Major Clades in the Sunflower Family KI-JOONG KIM* and ROBERT K

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 10379-10383, October 1995 Evolution ndhF sequence evolution and the major clades in the sunflower family KI-JOONG KIM* AND ROBERT K. JANSENt Department of Botany, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78713-7640 Communicated by Peter H. Raven, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, June 21, 1995 ABSTRACT An extensive sequence comparison of the either too short or too conserved to provide adequate numbers chloroplast ndhF gene from all major clades of the largest of characters in recently evolved families. A number of alter- flowering plant family (Asteraceae) shows that this gene native genes have been suggested as potential candidates for provides -3 times more phylogenetic information than rbcL. phylogenetic comparisons at lower taxonomic levels (9). The This is because it is substantially longer and evolves twice as phylogenetic utility of one of these, matK, has been recently fast. The 5' region (1380 bp) ofndhF is very different from the demonstrated (10). Comparison of sequences of two chloro- 3' region (855 bp) and is similar to rbcL in both the rate and plast genomes (rice and tobacco), however, revealed only two the pattern of sequence change. The 3' region is more A+T- genes, rpoCl and ndhF, that are considerably longer and evolve rich, has higher levels of nonsynonymous base substitution, faster than rbcL (9, 11). We selected ndhF because it is longer and shows greater transversion bias at all codon positions. and evolves slightly faster than rpoCl (11), because rpoCl has These differences probably reflect different functional con- an intron that may require additional effort in DNA amplifi- straints on the 5' and 3' regions of nduhF. -

Coreopsis Lanceolata) in Roadside Right-Of-Ways1 Jeffrey G

ENH1103 Establishment of Lanceleaf Tickseed (Coreopsis lanceolata) in Roadside Right-of-Ways1 Jeffrey G. Norcini, Anne L. Frances, and Carrie Reinhardt Adams2 Introduction The Florida Department of Transportation’s (FDOT) roadside right-of-way (ROW) wildflower program began in 1963 (3). In addition to the aesthetic attributes of wildflower plantings, FDOT noted that the plantings would increase driver alertness and would also lower maintenance costs. The economic benefit is even more relevant today because maintenance expenses are driven by higher fuel, labor, and equipment costs. The economic value of using native wildflowers in ROWs, especially native wildflowers adapted to Florida’s environ- ment (often referred to as Florida ecotypes) began to be Figure 1. A roadside right-of-way planting of lanceleaf tickseed. recognized in the 1980s (3). Today, the ecological value Lanceleaf Tickseed and sustainability of using native wildflowers adapted to Lanceleaf tickseed occurs throughout most of the United specific regions of the country is widely acknowledged States, the main exception being the Rocky Mountain states (5). And when plantings of these types of wildflowers are (12). In Florida, the documented range of this upland established and managed appropriately, maintenance costs species extends southward into Lake County (14). Lanceleaf are minimized, as is the need to replant. tickseed frequently occurs in sandhills and disturbed habitats, including roadside ROWs. The northern Florida lanceleaf tickseed ecotype is a low-growing (6–8 inches tall), short-lived perennial that 1. This document is ENH1103, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date July 2008. Revised March 2009.