Arxiv:1912.01335V4 [Physics.Atom-Ph] 14 Feb 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Hartree-Fock Molecular Orbital Theory

An Introduction to Hartree-Fock Molecular Orbital Theory C. David Sherrill School of Chemistry and Biochemistry Georgia Institute of Technology June 2000 1 Introduction Hartree-Fock theory is fundamental to much of electronic structure theory. It is the basis of molecular orbital (MO) theory, which posits that each electron's motion can be described by a single-particle function (orbital) which does not depend explicitly on the instantaneous motions of the other electrons. Many of you have probably learned about (and maybe even solved prob- lems with) HucÄ kel MO theory, which takes Hartree-Fock MO theory as an implicit foundation and throws away most of the terms to make it tractable for simple calculations. The ubiquity of orbital concepts in chemistry is a testimony to the predictive power and intuitive appeal of Hartree-Fock MO theory. However, it is important to remember that these orbitals are mathematical constructs which only approximate reality. Only for the hydrogen atom (or other one-electron systems, like He+) are orbitals exact eigenfunctions of the full electronic Hamiltonian. As long as we are content to consider molecules near their equilibrium geometry, Hartree-Fock theory often provides a good starting point for more elaborate theoretical methods which are better approximations to the elec- tronic SchrÄodinger equation (e.g., many-body perturbation theory, single-reference con¯guration interaction). So...how do we calculate molecular orbitals using Hartree-Fock theory? That is the subject of these notes; we will explain Hartree-Fock theory at an introductory level. 2 What Problem Are We Solving? It is always important to remember the context of a theory. -

Hartree-Fock Approach

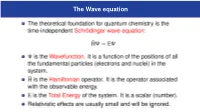

The Wave equation The Hamiltonian The Hamiltonian Atomic units The hydrogen atom The chemical connection Hartree-Fock theory The Born-Oppenheimer approximation The independent electron approximation The Hartree wavefunction The Pauli principle The Hartree-Fock wavefunction The L#AO approximation An example The HF theory The HF energy The variational principle The self-consistent $eld method Electron spin &estricted and unrestricted HF theory &HF versus UHF Pros and cons !er ormance( HF equilibrium bond lengths Hartree-Fock calculations systematically underestimate equilibrium bond lengths !er ormance( HF atomization energy Hartree-Fock calculations systematically underestimate atomization energies. !er ormance( HF reaction enthalpies Hartree-Fock method fails when reaction is far from isodesmic. Lack of electron correlations!! Electron correlation In the Hartree-Fock model, the repulsion energy between two electrons is calculated between an electron and the a!erage electron density for the other electron. What is unphysical about this is that it doesn't take into account the fact that the electron will push away the other electrons as it mo!es around. This tendency for the electrons to stay apart diminishes the repulsion energy. If one is on one side of the molecule, the other electron is likely to be on the other side. Their positions are correlated, an effect not included in a Hartree-Fock calculation. While the absolute energies calculated by the Hartree-Fock method are too high, relative energies may still be useful. Basis sets Minimal basis sets Minimal basis sets Split valence basis sets Example( Car)on 6-3/G basis set !olarized basis sets 1iffuse functions Mix and match %2ective core potentials #ounting basis functions Accuracy Basis set superposition error Calculations of interaction energies are susceptible to basis set superposition error (BSSE) if they use finite basis sets. -

The Hartree-Fock Method

An Iterative Technique for Solving the N-electron Hamiltonian: The Hartree-Fock method Tony Hyun Kim Abstract The problem of electron motion in an arbitrary field of nuclei is an important quantum mechanical problem finding applications in many diverse fields. From the variational principle we derive a procedure, called the Hartree-Fock (HF) approximation, to obtain the many-particle wavefunction describing such a sys- tem. Here, the central physical concept is that of electron indistinguishability: while the antisymmetry requirement greatly complexifies our task, it also of- fers a symmetry that we can exploit. After obtaining the HF equations, we then formulate the procedure in a way suited for practical implementation on a computer by introducing a set of spatial basis functions. An example imple- mentation is provided, allowing for calculations on the simplest heteronuclear structure: the helium hydride ion. We conclude with a discussion of how to derive useful chemical information from the HF solution. 1 Introduction In this paper I will introduce the theory and the techniques to solve for the approxi- mate ground state of the electronic Hamiltonian: N N M N N 1 X 2 X X ZA X X 1 H = − ∇i − + (1) 2 rAi rij i=1 i=1 A=1 i=1 j>i which describes the motion of N electrons (indexed by i and j) in the field of M nuclei (indexed by A). The coordinate system, as well as the fully-expanded Hamiltonian, is explicitly illustrated for N = M = 2 in Figure 1. Although we perform the analysis 2 Kim Figure 1: The coordinate system corresponding to Eq. -

![Arxiv:1411.4673V1 [Hep-Ph] 17 Nov 2014 E Unn Coupling Running QED Scru S Considerable and Challenge](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1578/arxiv-1411-4673v1-hep-ph-17-nov-2014-e-unn-coupling-running-qed-scru-s-considerable-and-challenge-2381578.webp)

Arxiv:1411.4673V1 [Hep-Ph] 17 Nov 2014 E Unn Coupling Running QED Scru S Considerable and Challenge

Attempts at a determination of the fine-structure constant from first principles: A brief historical overview U. D. Jentschura1, 2 and I. N´andori2 1Department of Physics, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, Missouri 65409-0640, USA 2MTA–DE Particle Physics Research Group, P.O.Box 51, H–4001 Debrecen, Hungary It has been a notably elusive task to find a remotely sensical ansatz for a calculation of Sommer- feld’s electrodynamic fine-structure constant αQED ≈ 1/137.036 based on first principles. However, this has not prevented a number of researchers to invest considerable effort into the problem, despite the formidable challenges, and a number of attempts have been recorded in the literature. Here, we review a possible approach based on the quantum electrodynamic (QED) β function, and on algebraic identities relating αQED to invariant properties of “internal” symmetry groups, as well as attempts to relate the strength of the electromagnetic interaction to the natural cutoff scale for other gauge theories. Conjectures based on both classical as well as quantum-field theoretical considerations are discussed. We point out apparent strengths and weaknesses of the most promi- nent attempts that were recorded in the literature. This includes possible connections to scaling properties of the Einstein–Maxwell Lagrangian which describes gravitational and electromagnetic interactions on curved space-times. Alternative approaches inspired by string theory are also dis- cussed. A conceivable variation of the fine-structure constant with time would suggest a connection of αQED to global structures of the Universe, which in turn are largely determined by gravitational interactions. PACS: 12.20.Ds (Quantum electrodynamics — specific calculations) ; 11.25.Tq (Gauge field theories) ; 11.15.Bt (General properties of perturbation theory) ; 04.60.Cf (Gravitational aspects of string theory) ; 06.20.Jr (Determination of fundamental constants) . -

Restricted Closed Shell Hartree Fock Roothaan Matrix Method Applied to Helium Atom Using Mathematica Introduction the Hartree Fo

European J of Physics Education Volume 5 Issue 1 2014 Acosta, Tapia, Cab Restricted Closed Shell Hartree Fock Roothaan Matrix Method Applied to Helium Atom using Mathematica César R. Acosta*1 J. Alejandro Tapia1 César Cab1 1Av. Industrias no Contaminantes por anillo periférico Norte S/N Apdo Postal 150 Cordemex Physics Engineering Department Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán *[email protected] (Received: 20.12. 2013, Accepted: 13.02.2014) Abstract Slater type orbitals were used to construct the overlap and the Hamiltonian core matrices; we also found the values of the bi-electron repulsion integrals. The Hartree Fock Roothaan approximation process starts with setting an initial guess value for the elements of the density matrix; with these matrices we constructed the initial Fock matrix. The Mathematica software was used to program the matrix diagonalization process from the overlap and Hamiltonian core matrices and to make the recursion loop of the density matrix. Finally we obtained a value for the ground state energy of helium. Keywords: STO, Hartree Fock Roothaan approximation, spin orbital, ground state energy. Introduction The Hartree Fock method (Hartree, 1957) also known as Self Consistent Field (SCF) could be made with two types of spin orbital functions, the Slater Type Orbitals (STO) and the Gaussian Type Orbital (GTO), the election is made in function of the integrals of spin orbitals implicated. We used the STO to construct the wave function associated to the helium atom electrons. The application of the quantum mechanical theory was performed using a numerical method known as the finite element method, this gives the possibility to use the computer for programming the calculations quickly and efficiently (Becker, 1988; Brenner, 2008; Thomee, 2003; Reddy, 2004). -

Total Energy of Benzene Within Hartree-Fock Approximation

Example I: Total energy of Benzene within Hartree-Fock approximation In this example we will calculate the total energy of the benzene using the Hartree-Fock (HF) approximation. Let us look at the input file The first directive “echo” is optional but highly recommended. Its purpose is to write out the contents of your input file into the output echo file. The “title” is also optional. You might want to put a short sentence identifying the nature of your calculation . title "total energy of benzene, HF/3-21G" The “start” directive is required. It indicates that this is a new calculation and sets up the name of the database to store your results. start c6h6-scf The name of the database file that you would like to associate with this calculation scratch_dir ./scratch The location of permanent and scratch permanent_dir ./perm directories. The scratch directory contains temporary files. The permanent directory contains essential files which will be required should you wish to restart your calculation The geometry block specifies the name of the elements that comprise your system as well as their coordinates in the following format: Name1 x1 y1 z1 Name2 x2 y2 z2 …… Unless indicated otherwise the default units are angstroms, and the system will be centered around the origin. geometry C 0.99261000 0.99261000 0.00000000 C -1.35593048 0.36332048 0.00000000 C 0.36332048 -1.35593048 0.00000000 C -0.99261000 -0.99261000 0.00000000 C 1.35593048 -0.36332048 0.00000000 C -0.36332048 1.35593048 0.00000000 H 1.75792000 1.75792000 0.00000000 H -2.40136338 0.64344338 0.00000000 H 0.64344338 -2.40136338 0.00000000 H -1.75792000 -1.75792000 0.00000000 H 2.40136338 -0.64344338 0.00000000 H -0.64344338 2.40136338 0.00000000 end The basis block defines which Gaussian basis sets are to be used with the HF calculation. -

Hartfock.Pdf

Copyright c 2019 by Robert G. Littlejohn Physics 221B Spring 2020 Notes 31 The Hartree-Fock Method in Atoms † 1. Introduction The Hartree-Fock method is a basic method for approximating the solution of many-body electron problems in atoms, molecules, and solids. With modifications, it is also extensively used for protons and neutrons in nuclear physics, and in other applications. In the Hartree-Fock method, one attempts to find the best multi-particle state that can be represented as a Slater determinant of single particle states, where the criterion for “best” is the usual one in the variational method in quantum mechanics. For the Hartree-Fock method, this means that the expectation value of the energy should be stationary with respect to variations in the single particle orbitals. Hartree- Fock solutions are often used as a starting point for a perturbation analysis, which is capable of giving more accurate approximations. In these notes, we discuss the Hartree-Fock method in atomic physics. Later we will use it as the basis of a perturbation analysis that reveals the basic facts about atomic structure in multielectron atoms. This is our first excursion into the physics of systems with more than two identical particles, and we will use it as an opportunity to elaborate on the symmetrization postulate in the context of a practical example. 2. The Basic N-electron Hamiltonian The Hamiltonian we wish to solve initially is the nonrelativistic, electrostatic approximation for an atom with N electrons and nuclear charge Z. We do not necessarily assume N = Z, so we leave open the possibility of dealing with ions. -

1 I. Units and Conversions 1 A. Atomic Units 1 B. Energy Conversions 2 II

1 CONTENTS I. Units and Conversions 1 A. Atomic Units 1 B. Energy Conversions 2 II. Approximation Methods 2 A. Semiclassical quantization 2 B. Time-independent perturbation theory 4 C. Linear variational method 7 D. Orthogonalization 11 1. Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization 11 2. Diagonalization of the overlap matrix 12 E. MacDonald’s Theorem 14 F. DVR method for bound state energies 16 References 21 I. UNITS AND CONVERSIONS A. Atomic Units Throughout these notes we shall use the so-called Hartree atomic units in which mass is reckoned in units of the electron mass (m = 9.1093826 10−31 kg) and distance in terms e × of the Bohr radius (a =5.299175 10−2 nm). In this system of units the numerical values 0 × of the following four fundamental physical constants are unity by definition: Electron mass m • e Elementary charge e • reduced Planck’s constant ~ • Coulomb’s constant 1/4πǫ • 0 The replacement of these constants by unity will greatly simplify the notation. 2 It is easiest to work problems entirely in atomic units, and then convert at the end to SI units, using Length (Bohr radius) 1a =5.299175 10−2 nm = 0.5291775 A˚ • 0 × Energy (Hartree) 1E =4.35974417 10−18 J • h × B. Energy Conversions Atomic (Hartree) units of energy are commonly used by theoreticians to quantify elec- tronic energy levels in atoms and molecules. From an experimental viewpoint, energy levels are often given in terms of electron volts (eV), wavenumber units, or kilocalories/mole (kcal/mol). From Planck’s relation hc E = hν = λ The relation between the Joule and the kilocalorie is 1kcal = 4.184 kJ Thus, 1 kcal/mole is one kilocalorie per mole of atoms, or 4.184 103 J divided by Avogadro’s × number (6.022 1023) = 6.9479 10−21 J/molecule. -

Hartree-Fock Method

KH Computational Physics- 2009 Hartree-Fock Method Hartree-Fock It is probably the simplest method to treat the many-particle system. The dynamic many particle problem is replaced by an effective one-electron problem: electron is moving in an effective static potential field. It can be viewed as a variational method where the full many-body wave function is replaced by a single Slater determinant. The elements of the determinant are one electron orbitals with orbital and spin part. It can also be viewed as the lowest order term in perturbative expansion (linear in U) with respect to interaction between electrons. These two views will be substantiated below by equations. But first we will use decoupling method to derive the Hartree-Fock equations. Kristjan Haule, 2009 –1– KH Computational Physics- 2009 Hartree-Fock Method In the second quantization, the many electron problem takes the form 1 2 1 H = drΨ†(r)[ +V (r)]Ψ(r)+ drdr′Ψ†(r)Ψ†(r′)v (r r′)Ψ(r′)Ψ(r) −2∇ ext 2 c − Z Z (1) where Ψ(r) is the field operator of electron, Vext(r) is the potential of nucleous and v (r r′) is the Coulomb interaction 1/ r r′ . We assumed Born-Oppenheimer c − | − | approximation for nuclei motion (freezing them since their kinetic energy is of the order of Mnuclei/me). The Hartree-Fock approximation replaces the two-body interaction term by an effective one body term Ψ†(r)Ψ†(r′)Ψ(r′)Ψ(r) Ψ†(r)Ψ(r) Ψ†(r′)Ψ(r′)+ Ψ†(r′)Ψ(r′) Ψ†(r)Ψ(r) (2) → h i h i Ψ†(r)Ψ(r′) Ψ†(r′)Ψ(r) Ψ†(r′)Ψ(r) Ψ†(r)Ψ(r′) (3) −h i − h i With the generalized density ρ(r, r′)= Ψ†(r)Ψ(r′) the effective -

The Hartree-Fock Method Applied to Helium's Electrons

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Chemistry Education Materials Department of Chemistry 2009 The aH rtree-Fock Method Applied to Helium's Electrons Carl W. David University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/chem_educ Part of the Physical Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation David, Carl W., "The aH rtree-Fock Method Applied to Helium's Electrons" (2009). Chemistry Education Materials. 72. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/chem_educ/72 The Hartree Fock Method Applied to Helium's Electrons C. W. David (Dated: March 5, 2009) I. SYNOPSIS where Z = 2 for Helium. For the ground state, we write the spatial part of the The difficulties of applying the Hartree-Fock method to wave function as many body problems is illustrated by treating Helium's electrons up to the point where tractability vanishes. Second, the problem of applying Hartree-Fock methods = φ1(r1)φ1(r2) to the helium atom's electrons, when they are constrained to remain on a sphere, is revisited. The 6-dimensional total energy operator is reduced to a 2-dimensional one, i.e., spatially symmetric, since we know that the spin part and the application of that 2-dimensional operator in the (α(1); β(2) − α(2)β(1))is going to be antisymmetric. Hartree-Fock mode is discussed. We seek a \solution" of the equation II. HELIUM HAMILTONIAN AND STARTING ^ WAVE FUNCTION APPROXIMATIONS H Hop = E We start with the Hamiltonian (in symbolic form): which becomes ^ ^ ^ 1 Hop = H1 + H2 + r12 1 H^1 + H^2 + φ1(r1)φ1(r2) = Eφ1(r1)φ1(r2) -

23. the Hydrogen Atom Copyright C 2015–2016, Daniel V

23. The Hydrogen Atom Copyright c 2015{2016, Daniel V. Schroeder The most important example of a spherically symmetric potential energy is the Coulomb potential, 1 q q V (r) = 1 2 ; (1) 4π0 r between two point charges q1 and q2 separated by a distance r. If one of the two charges is a heavy atomic nucleus and the other is a much lighter electron, then to a good approximation we can treat the nucleus as a fixed center of force and apply quantum mechanics only to the electron's motion (see Problem 5.1 in Griffiths if you want to know how accurate this approximation is). In terms of the fundamental unit of charge, e = 1:602 × 10−19 C; (2) the electron's charge is −e and the nuclear charge is Ze, where Z is the number of protons. For now we'll consider only the hydrogen atom, with Z = 1, so the potential energy is e2 1 V (r) = − : (3) 4π0 r Given this potential energy function, we can immediately write down the effec- tive potential, ¯h2l(l + 1) e2 1 Veff(r) = 2 − ; (4) 2mr 4π0 r where m is the electron's mass, and then use this Veff in the (reduced) radial Schr¨odingerequation, ¯h2 d2 − + V (r) u(r) = Eu(r): (5) 2m dr2 eff Natural units It looks like the TISE for the hydrogen atom involves four different constants: e, 0, m, andh ¯. But they occur in only two different combinations, e2 ¯h2 and ; (6) 4π0 m and you can immediately see from equation 4 that these combinations have dimen- sions of energy times distance and energy times distance squared, respectively. -

Natural Units

Natural units Peter Hertel Overview Normal matter Natural units Atomic units Length and energy Electric and Peter Hertel magnetic fields More University of Osnabr¨uck,Germany examples Lecture presented at APS, Nankai University, China http://www.home.uni-osnabrueck.de/phertel October/November 2011 • Normal matter • Atomic units • SI to AU conversion Natural units Overview Peter Hertel Overview Normal matter Atomic units Length and energy Electric and magnetic fields More examples • Atomic units • SI to AU conversion Natural units Overview Peter Hertel Overview Normal matter Atomic units Length and energy Electric and magnetic fields • Normal matter More examples • SI to AU conversion Natural units Overview Peter Hertel Overview Normal matter Atomic units Length and energy Electric and magnetic fields • Normal matter More examples • Atomic units Natural units Overview Peter Hertel Overview Normal matter Atomic units Length and energy Electric and magnetic fields • Normal matter More examples • Atomic units • SI to AU conversion • normal matter is governed by electrostatic forces and non-relativistic quantum mechanics • heavy nuclei are surrounded by electrons neutral atoms, molecules, liquids and solids • Planck's constant ~ • unit charge e • electron mass m • 4π0 from Coulomb's law • typical values for normal matter are reasonable numbers • times products of powers of these constants Natural units Normal matter Peter Hertel Overview Normal matter Atomic units Length and energy Electric and magnetic fields More examples • heavy nuclei are surrounded