Table of Contents Volume 18 EDITOR's NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lrtsv11no4.Pdf

EDITORIAL BOARD Editor, and Chairman of the Editorial Board Peur S. DuNxrn Assistant Editors: RrcnennM. Doucnrnry ...... for Acquisitions Section C. DoNern Coor for Cataloging and Classification Section ELIzasnrH F. Nonrox .. .. for Serials Section AnnN B. VreNnn for Reproduction of Library Materials Section Editorial Aduisers: Maurice F. Tauber (for Technical Services) Louis A. Schultheiss (for Regional Groups) Managing Editor: . Donar-vN J. Hrcr<nv Circulation Manager: .. Mns. ErrzesnrH Roonn Li,brary Resources ,lr Technical Seruices, the quarterly official publication of the Resources and Technical Services Division of the American Library Association is pub- lished at zgor Byrdhill Road, Richmond, Va. zgzog. Editorial Office: Graduate School of Library Service, Rutgers-The State University, New Brunswick, N. J. o89o3. Clr- culati.on and Business Office:5o E. Huron St., Chicago, Ill.6o6rr. Subscripti.on Price: to members of the ALA Resources and Technical Services Division, $z.oo per year, included in the membership dues; to nonmembers, $5.oo per year, single copies $r.25, orders of five or more copies (same issue or assorted),$r.oo each. "Second-classpostage paid at Richmond, Va., and at additional mailing offices." -LRTS is indexed in Library Literature and in Library Sci.enceAbstracts. Its reviews are included in tlae Book Reuiew Digest and. Book Reuieu Index. Editors: Material published in ZR?S is not copyrighted. When reprinting the courtesy of citation to the original publication is requested. Publication in IRTS does not imply official endorsement by the Resources and Technical Services Division nor by ALA, and the assumption of editorial responsibility is not to be construed necessarily as endorsement of the opinions expressed by individual contributors. -

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916 Table of Contents OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES .......................................................................................5 PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH TO THIRTY-NINTH MEETINGS .............................................................................................7 PAPERS EXTRACTS FROM LETTERS OF THE REVEREND JOSEPH WILLARD, PRESIDENT OF HARVARD COLLEGE, AND OF SOME OF HIS CHILDREN, 1794-1830 . ..........................................................11 By his Grand-daughter, SUSANNA WILLARD EXCERPTS FROM THE DIARY OF TIMOTHY FULLER, JR., AN UNDERGRADUATE IN HARVARD COLLEGE, 1798- 1801 ..............................................................................................................33 By his Grand-daughter, EDITH DAVENPORT FULLER BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MRS. RICHARD HENRY DANA ....................................................................................................................53 By MRS. MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI EARLY CAMBRIDGE DIARIES…....................................................................................57 By MRS. HARRIETTE M. FORBES ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TREASURER ........................................................................84 NECROLOGY ..............................................................................................................86 MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................................89 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY -

80 SAY WE ALL of US JUST ONE Theres but One BEST Cyclopaedia T

e +v n X 17c11 i vwfrflrs AbW J4 xn rrmar yrry rD vrA4F ltnVti- H wr Sy w IMf ivvrnnI1 i In a rm r II THE SUN SUNDAY MARCH 9 1902 I- r y l r 11- f t t 80 SAY WE ALL OF US JUST ONE Theres But One BEST Cyclopaedia t I The Only American I r The Only American I i P P L E 0 N e I n r versal CycIopdia and Atlas i I DEWEY JAMES H CANFIELD WILLIAM T HARRIS MELVIL s CARDINAL GIBBONS HENRY A BEERS Library Librarian of Columbia University PREST ARTHUR T HADLEY Uni-¬ Commissioner of Education Director State 3 REV DR NEWELL DWIflHT HILLII Md Pro of Literature Yale N Y Yale University Baltimore Washington D Albany r Plymouth Church versity New Haven Conn J H BLAUDELL Brooklyn N Y New Haven Conn WM MARSHALL STEVENSON L HOWARD FERRIS FRANCIS WAYLAND Supt of Schools Librarian Allegheny Pa CADY STALEY N H RANDALL SPAULDING Science Hamilton County Probate Court Dean of Law School- Laconia GEO EDWARD REED Schools Case School of Supt of REV T H ROBINSON Cleveland Cincinnati O State Librarian N J 0 C A LINDSLEY Montclair Western Theological Seminary E BENJAMIN ANDREWS DR Harrisburg Pa State Board of Health B Pa DAVID S SCHAFF W 0 THOMPSON D D LL D ExPresident Brown University Secty WM DAVENPORT Atty New Haven Conn RUPP Lane Seminary President Miami University GEO P 189 Montague St JOHN A BROADUS D D LLD Librarian Brooklyn N Y Cincinnati 0 O JAMES K JEWETT + i Southern Seminary Languagea VERY REV J A MULCAHY t Philadelphia Pa Louisville Asso Prol Semitic s WM C GORMAN J REMSEN BISHOP MARGARET W SUTHERLAND and History Brown University Late Rector of St Patrlekr -

The Riant Collection in the Harvard College Library

Among Harvard's Libraries: The Riant Collection in the Harvard College Library The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Walsh, James E. 1996. Among Harvard's Libraries: The Riant Collection in the Harvard College Library. Harvard Library Bulletin 6 (2), Summer 1995: 5-9. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42665376 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Among Harvard's Libraries 5 THE RIANT COLLECTION IN THE HARVARD have visited Picard in Paris, for on 30 Septem- CoLLEGE LIBRARY ber 1899 he wrote to Lane: Will you kindly submit to the Library James E. Walsh Council the following proposition for n 29 March 1896 the Parisian bookseller the purchase of the Riant Collection 0 A. Picard, agent for the sale of the Riant whose catalogue you have now in Collection, wrote to Justin Winsor, librarian your hands. If the Harvard Library will of Harvard College: contribute two thousand dollars to this purchase and take the necessary steps, Je suis charge de negocier la vente I agree that the two thousand remain- d'une Bibliotheque fort importante et ing from my Father's gift oflast year be d'un interet fort particulier. II s' agit de devoted to the same purpose; I offer la collection des livres Scandinaviens two thousand more in his name, and I assemblee par feu Monsieur le Comte undertake to guarantee the remainder, Riant dont je vous envoie d'ailleurs le up to the sum of ten thousand dollars, catalogue par le meme courir. -

The Authors of Articles in This Number of the Harvard Theological Review

THE AUTHORS OF ARTICLES IN THIS NUMBER OF THE HARVARD THEOLOGICAL REVIEW GEORGE HODGES, A.M., D.D., D.C.L., LL.D., Dean of the Episcopal Theological School, Cambridge. Author: The Episcopal Church; Christianity Between Sundays; The Heresy of Cain; In this Present World; Faith and Social Service; The Battles of Peace; The Path of Life; William Perm; Fountains Abbey; The Human Nature of the Saints; When the King Came; The Cross and Passion; Three Hundred Years of the Episcopal Church in America; The Administration of an Institutional Church; The Happy Family; The^ Pursuit of Happiness; The Year of Grace; Holderness; The Apprenticeship of Washington; The Garden of Eden; The Training qf Children in Religion; A Child's Guide to the Bible; Everyman's Relig- ion; Saints and Heroes; Class Book of Old Testament History; The Early Church; Henry Codman Potter, Seventh Bishop of New York; Religion in a World of War; How to Know the Bible. EPHRAIM EMERTON, Ph.D., Winn Professor of Ecclesiastical History, Emeritus, in Harvard University. Author: Introduction to the Study of the Middle Ages; Synopsis of the History of Continental Europe; Mediaeval Europe, 814-1300; Desid- erius Erasmus; Unitarian Thought; Beginnings of Modern Europe. JAMES BISSETT PRATT, A.M.,Ph.D., Professor of Philosophy in Williams College. Author: The Psychology of Religious Belief; What is Pragmatism? India and its Faith; Democracy and Peace. WILLIAM HALLOCK JOHNSON, Ph.D., D.D., Professor of Greek and New Testament Literature in Lincoln University, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Author: The Free-will Problem in Modem Thought; The Christian Faith under Modern Searchlights. -

Marche. at Ington Shoe Buyer Knows M FACTS HO?I BH0DGBT to LIGHT Between $7.50 and $25 We

0 TOMORROW, TOMORRi IW, V t MeKmew's, TRIM MH) VQ SI'ITS Men's HATH, Q | Spuing § "Strictlv reliable 1 WORTH WORTH qualities." !#H:WMI How He Securted Sis Appointment as Bon >n< $12. $15 AND $10.30, 16.50. fT.SU AND ftt 00. Shoe K< librarian. * I Sofits, t Friday's Bargains m $4.98. ments Everywell-posted Wash¬ !?I1 Marche. At ington Shoe buyer knows m FACTS HO?I BH0DGBT TO LIGHT Between $7.50 and $25 we . are . f 11 I »M« iRROIt we our bljr . that some extraordinary showing worth . everything . 11 new lid* s of Men'* Easter N>k Hahn <& Co.'s >Hi f . ?/ (1 SALE. in . can .FECIAL NOTION wonr. Gl»rt»'S »n<l Shirt*:. and Shoe bargains always having spring suits. * * >f«l || * . II w?'"\» some might v neat things Si Withdrew His First . 3 found at our stores worsteds and be Acceptance . to hIh>w the swell dressers (»f Busy Stores. V. B 3c. Clark's <). X. T. Darning Oottoo..lc. ball. 10c. Jars Petroleum Jelly i/ Fancy "herring¬ . «« . Washiin;ron. I>rop in tomorrow just We never 5c. Hand Scrub Brushes 2«\ 15c. bottle Violet Ammonia He. ^ bones" are fashion's favorites. every f«>r lc. lOc. Sr. Y for ;i I«H»k buy. if you want to. ¦H Friday. Under IIlimit Hooks ami Epea. 2 tloa. Bora ted Talcum Powder * Misapprehension. Oo-lnch Measures lc. Bon Man he White Toilet lc. ake. have any old stock.any > <. Tape Soap Q and nowhere else will find "'aper of 200 Pins If. -

Harvard Theological Review the Beginnings of Modern Europe

Harvard Theological Review http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR Additional services for Harvard Theological Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Beginnings of Modern Europe (1250– 1458). Ephraim Emerton. Ginn & Co. 1918. Pp. xiv, 550. Maps. \$1.80. Dana C. Munro Harvard Theological Review / Volume 12 / Issue 02 / April 1919, pp 241 - 243 DOI: 10.1017/S0017816000010579, Published online: 03 November 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S0017816000010579 How to cite this article: Dana C. Munro (1919). Review of Josiah Gilbert, and G. C. Churchill 'The Dolomite Mountains' Harvard Theological Review, 12, pp 241-243 doi:10.1017/S0017816000010579 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 128.122.253.228 on 25 Apr 2015 BOOK REVIEWS 241 religious crisis as more of an intellectual than of a mystical char- acter is entirely new and wholly original, but certainly it has never been propounded in such a definite way and so well harmonized with the whole of Augustine's intellectual and spiritual career, in a vigor- ous synthesis of his life and his theology. Being a work of synthesis, there is no room for details in the book. As for the synthesis itself, like all syntheses, it has a personal element, which, however, does not at all diminish the objective value of the study. G. F. LA PIANA. HARVARD UNIVEBSITY. THE BEGINNINGS OP MODERN EUROPE (1250-1458). EPHRAIM EMERTON. Ginn & Co. 1918. Pp. xiv, 550. Maps. $1.80. The publication of this new volume by Professor Emerton is an event of great interest to a host of his students and friends. -

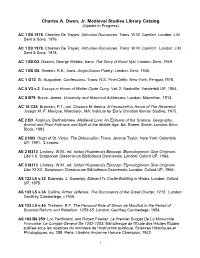

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

38037732 Lese 1.Pdf

Archive for Reformation History An international journal concerned with the history of the Reformation and its significance in world affairs, published under the auspices of the Verein für Reformationsgeschichte and the Society for Reformation Research Board of Editors Jodi Bilinkoff, Greensboro/North Carolina – Gérald Chaix, Nantes – David Cressy, Columbus/Ohio – Michael Driedger, St. Catharines/Ontario – Mark Greengrass, Sheffield – Brad S. Gregory, Notre Dame/Indiana – Scott Hendrix, Princeton/New Jersey – Mack P. Holt, Fairfax/Virginia – Susan C. Karant-Nunn, Tucson/Arizona – Thomas Kaufmann, Göttingen – Ernst Koch, Leipzig – Ute Lotz-Heumann, Tucson/ Arizona – Janusz Małłek, Toruń – Silvana Seidel Menchi, Pisa – Bernd Moeller, Göttingen – Carla Rahn Phillips, Minneapolis/Minnesota – Heinz Scheible, Heidel- berg – Heinz Schilling, Berlin – Anne Jacobson Schutte, Charlottesville/Virginia – Christoph Strohm, Heidelberg – James D. Tracy, Minneapolis/Minnesota – Randall C. Zachman, Notre Dame/Indiana North American Managing Editors Brad S. Gregory – Randall C. Zachman European Managing Editor Ute Lotz-Heumann Vol. 104 · 2013 Gütersloher Verlagshaus Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte Internationale Zeitschrift zur Erforschung der Reformation und ihrer Weltwirkungen, herausgegeben im Auftrag des Vereins für Reformationsgeschichte und der Society for Reformation Research Herausgeber Jodi Bilinkoff, Greensboro/North Carolina – Gérald Chaix, Nantes – David Cressy, Columbus/Ohio – Michael Driedger, St. Catharines/Ontario – Mark Greengrass, Sheffield – Brad S. Gregory, Notre Dame/Indiana – Scott Hendrix, Princeton/New Jersey – Mack P. Holt, Fairfax/Virginia – Susan C. Karant-Nunn, Tucson/Arizona – Thomas Kaufmann, Göttingen – Ernst Koch, Leipzig – Ute Lotz-Heumann, Tucson/ Arizona – Janusz Małłek, Toruń – Silvana Seidel Menchi, Pisa – Bernd Moeller, Göttingen – Carla Rahn Phillips, Minneapolis/Minnesota – Heinz Scheible, Heidel- berg – Heinz Schilling, Berlin – Anne Jacobson Schutte, Charlottesville/Virginia – Christoph Strohm, Heidelberg – James D. -

The Harvard Bindery: a Short History Weissman Preservation Center, Harvard University Library

The Harvard Bindery: A Short History Weissman Preservation Center, Harvard University Library Sarah K. Burke Spring 2010 The history of bookbinding is the history of a craft that, like printing, began with handmade tools in a workshop and developed into a mechanized industry capable of a tremendous output of product. The field has become so specialized that there is a particular set of materials and practices designed to increase the durability (and thus the longevity) of books and serials for use in library collections: library binding. Although libraries have always bound and re-bound books, standardized library binding procedures are a product of the past 150 years. Practically speaking, a book’s binding makes it sturdier by reinforcing its spine and allowing it to open with minimal damage. It also offers the book’s text block some degree of protection from pests and the elements. Rebinding a book may become necessary if the original binding is damaged or if the text block is falling out of its binding. In the case of serial literature and loose items, binding can keep volumes in order. As early as 1851, for example, Harvard’s early manuscript records were bound together, “for their preservation and for preventing future loss.”1 Consistent colors, fonts, or styles of binding are also useful for arrangement and security of library materials. Despite its many virtues, bookbinding has sometimes led to the destruction of important artifactual information, or to the creation of a tightly-bound book that is easily damaged by users. William Blades devoted an entire chapter of The Enemies of Books to the damage bookbinders have done to the “dignity, beauty, and value” of printed pages.2 Too often in the past, libraries and private collectors have had historically important bindings stripped from books in order to replace them with more elegant or uniform bindings. -

Lieutenant George Inman

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 19, 1926 Volume Nineteen Table Of Contents Publishing Note PROCEEDINGS SEVENTY-THIRD MEETING.....................................................................5 SEVENTY-FOURTH MEETING..................................................................7 SEVENTY-FIFTH MEETING......................................................................8 SEVENTY-SIXTH MEETING.....................................................................8 PAPERS CAMBRIDGE HISTORY IN THE CAMBRIDGE SCHOOLS.............................9 BY LESLIE LINWOOD CLEVELAND THE RIVERSIDE PRESS........................................................................15 BY JAMES DUNCAN PHILLIPS EARLY GLASS MAKING IN EAST CAMBRIDGE.........................................32 DORIS HAYES-CAVANAUGH LIEUTENANT GEORGE INMAN................................................................46 MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI REPORTS ANNUAL REPORT OF SECRETARY AND COUNCIL ..................................80 ANNUAL REPORT OF TREASURER.........................................................85 ANNUAL REPORT OF AUDITOR.............................................................86 REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON DESCENDANTS OF EARLY SET- TLERS OF CAMBRIDGE...................................................................88 OFFICERS..............................................................................................89 MEMBERS..............................................................................................90 -

Church History April

Church History Catalog April 2013 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 Email and Skype: [email protected] Website: http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store); Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- sorry, no phone). Our specialty is used and out-of-print academic books in the areas of theology, church history, biblical studies, and western philosophy. We operate an open shop and coffee house in downtown Eugene. Please stop by if you're ever in the area! When ordering, please reference our book number (shown in brackets at the end of each listing). Prepayment required of individuals. Credit cards: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover; or check/money order in US dollars. Books will be reserved 10 days while awaiting payment. Purchase orders accepted for institutional orders. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. We advise insuring orders of $100.00 or more. Insurance is available at 5% of the order's total, before shipping. Uninsured orders of $100.00 or more are sent at the customer's risk. Returns are accepted on the basis of inaccurate description. Please call before returning an item. __2000 Ans de Christianisme, Tome I__. Société d'Histoire Chrétienne. 1975. Hardcover, no dust jacket.. 288pp. Very good $10 [381061] . __2000 Ans de Christianisme, Tome II__.