Download Magazine Final Spreads.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hdpt-Car-Info-Bulletin-Eng-164.Pdf

Bulletin 164 01/03/10 – 15/03/11 | Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team | CAR www.hdptcar.net Newsletter 2011 fairs in Bouar and Bozoum Bouar Fair: Under the theme "the Future of Farmers, 01 – 15 March 2011 the Future of the Central African", the second edition of the agricultural fair organized by Mercy Corps and Caritas took place in Bouar, Nana-Mambere Highlights Prefecture (West) from 19 to 20 February. Some 104 agricultural groups and women’s associations - Inaugural swearing-in ceremony of President participated in this fair and obtained a profit of almost François Bozizé 19 million FCFA. Sales from a similar fair in 2010 - Refugees, Asylum Seekers and IDPs in CAR amounted to 15 million FCFA. Groups and associations managed by Mercy Corps also provided - Internews activities in CAR information on their activities. During this fair, a Food Bank set up by Caritas in partnership with the Background and security Association Zyango Be-Africa, was inaugurated. Various groups exhibited and sold products such as Inaugural swearing-in ceremony of the President millet, maize, sesame seeds, peanuts, coffee and On 15 March Francois Bozizé was sworn-in as rice. A separate section was also reserved for cattle, President of the Central African Republic for a second goat, chicken and guinea fowl breeders. Prizes were mandate of 5 years, by the Constitutional Court. awarded to 28 groups based on three main criteria: Francois Bozizé pledged to respect the Constitution exhibition, economic value and variety of products of CAR and to ensure the well being of Central exhibited. Prizes included two cassava mills donated Africans. -

Central African Republic Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #4 01-21

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2014 JANUARY 21, 2014 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA 1 F U N D I N G HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2014 Conditions in the Central African Republic (CAR) remain unstable, and insecurity continues to constrain 2.6 19% 19% humanitarian efforts across the country. million The U.S. Government (USG) provides an additional $30 million in humanitarian Estimated Number of assistance to CAR, augmenting the $15 People in CAR Requiring 12% million contributed in mid-December. Humanitarian Assistance U.N. Office for the Coordination of 26% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – December 2013 TO CAR IN FY 2014 24% USAID/OFDA $8,008,810 USAID/FFP2 $20,000,000 1.3 Health (19%) State/PRM3 $17,000,000 million Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (26%) Estimated Number of Logistics & Relief Commodities (24%) $45,008,810 Food-Insecure People Protection (12%) TOTAL USAID AND STATE in CAR ASSISTANCE TO CAR U.N. World Food Program (WFP) – Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (19%) December 2013 KEY DEVELOPMENTS 902,000 Since early December, the situation in CAR has remained volatile, following a pattern of Total Internally Displaced rapidly alternating periods of calm and spikes in violence. The fluctuations in security Persons (IDPs) in CAR conditions continue to impede humanitarian access and aid deliveries throughout the OCHA – January 2014 country, particularly in the national capital of Bangui, as well as in northwestern CAR. Thousands of nationals from neighboring African countries have been departing CAR 478,383 since late December, increasing the need for emergency assistance within the region as Total IDPs in Bangui countries strive to cope with returning migrants. -

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food. -

Africa's Role in Nation-Building: an Examination of African-Led Peace

AFRICA’S ROLE IN NATION-BUILDING An Examination of African-Led Peace Operations James Dobbins, James Pumzile Machakaire, Andrew Radin, Stephanie Pezard, Jonathan S. Blake, Laura Bosco, Nathan Chandler, Wandile Langa, Charles Nyuykonge, Kitenge Fabrice Tunda C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2978 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0264-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Air Force photo/ Staff Sgt. Ryan Crane; Feisal Omar/REUTERS. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the turn of the century, the African Union (AU) and subregional organizations in Africa have taken on increasing responsibilities for peace operations throughout that continent. -

Splintered Warfare Alliances, Affiliations, and Agendas of Armed Factions and Politico- Military Groups in the Central African Republic

2. FPRC Nourredine Adam 3. MPC 1. RPRC Mahamat al-Khatim Zakaria Damane 4. MPC-Siriri 18. UPC Michel Djotodia Mahamat Abdel Karim Ali Darassa 5. MLCJ 17. FDPC Toumou Deya Gilbert Abdoulaye Miskine 6. Séléka Rénovée 16. RJ (splintered) Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane Bertrand Belanga 7. Muslim self- defense groups 15. RJ Armel Sayo 8. MRDP Séraphin Komeya 14. FCCPD John Tshibangu François Bozizé 9. Anti-Balaka local groups 13. LRA 10. Anti-Balaka Joseph Kony 12. 3R 11. Anti-Balaka Patrice-Edouard Abass Sidiki Maxime Mokom Ngaïssona Splintered warfare Alliances, affiliations, and agendas of armed factions and politico- military groups in the Central African Republic August 2017 By Nathalia Dukhan Edited by Jacinth Planer Abbreviations, full names, and top leaders of armed groups in the current conflict Group’s acronym Full name Main leaders 1 RPRC Rassemblement Patriotique pour le Renouveau de la Zakaria Damane Centrafrique 2 FPRC Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique Nourredine Adam 3 MPC Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain Mahamat al-Khatim 4 MPC-Siriri Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain (Siriri = Peace) Mahamat Abdel Karim 5 MLCJ Mouvement des Libérateurs Centrafricains pour la Justice Toumou Deya Gilbert 6 Séleka Rénovée Séléka Rénovée Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane 7 Muslim self- Muslim self-defense groups - Bangui (multiple leaders) defense groups 8 MRDP Mouvement de Résistance pour la Défense de la Patrie Séraphin Komeya 9 Anti-Balaka local Anti-Balaka Local Groups (multiple leaders) groups 10 Anti-Balaka Coordination nationale -

OCHA CAR Snapshot Incident

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Overview of incidents affecting humanitarian workers January - May 2021 CONTEXT Incidents from The Central African Republic is one of the most dangerous places for humanitarian personnel with 229 1 January to 31 May 2021 incidents affecting humanitarian workers in the first five months of 2021 compared to 154 during the same period in 2020. The civilian population bears the brunt of the prolonged tensions and increased armed violence in several parts of the country. 229 BiBiraorao 124 As for the month of May 2021, the number of incidents affecting humanitarian workers has decreased (27 incidents against 34 in April and 53 in March). However, high levels of insecurity continue to hinder NdéléNdélé humanitarian access in several prefectures such as Nana-Mambéré, Ouham-Pendé, Basse-Kotto and 13 Ouaka. The prefectures of Haute-Kotto (6 incidents), Bangui (4 incidents), and Mbomou (4 incidents) Markounda Kabo Bamingui were the most affected this month. Bamingui 31 5 Kaga-Kaga- 2 Batangafo Bandoro 3 Paoua Batangafo Bandoro Theft, robbery, looting, threats, and assaults accounted for almost 60% of the incidents (16 out of 27), 2 7 1 8 1 2950 BriaBria Bocaranga 5Mbrès Djéma while the 40% were interferences and restrictions. Two humanitarian vehicles were stolen in May in 3 Bakala Ippy 38 2 Bossangoa Bouca 13 Bozoum Bouca Ippy 3 Bozoum Dekoa 1 1 Ndélé and Bangui, while four health structures were targeted for looting or theft. 1 31 2 BabouaBouarBouar 2 4 1 Bossangoa11 2 42 Sibut Grimari Bambari 2 BakoumaBakouma Bambouti -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

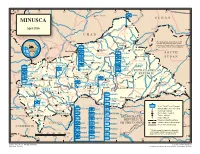

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Central African Republic in Crisis. African Union Mission Needs

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik ments German Institute for International and Security Affairs m Co Central African Republic in Crisis WP African Union Mission Needs United Nations Support Annette Weber and Markus Kaim S On 20 January 2014 the foreign ministers of the EU member-states approved EUFOR RCA Bangui. The six-month mission with about 800 troops is to be deployed as quickly as possible to the Central African Republic. In recent months CAR has witnessed grow- ing inter-religious violence, the displacement of hundreds of thousands of civilians and an ensuing humanitarian disaster. France sent a rapid response force and the African Union expanded its existing mission to 5,400 men. Since the election of the President Catherine Samba-Panza matters appear to be making a tentative turn for the better. But it will be a long time before it becomes apparent whether the decisions of recent weeks have put CAR on the road to solving its elementary structural problems. First of all, tangible successes are required in order to contain the escalating violence. That will require a further increase in AU forces and the deployment of a robust UN mission. In December 2012 the largely Muslim mili- infrastructure forces the population to tias of the Séléka (“Coalition”) advanced organise in village and family structures. from the north on the Central African The ongoing political and economic crises Republic’s capital Bangui. This alliance led of recent years have led to displacements by Michel Djotodia was resisted by the large- and a growing security threat from armed ly Christian anti-balaka (“anti-machete”) gangs, bandits and militias, and further militias. -

The Protracted Conflict in the Central African Republic and the Response of the International Communities

European Journal of Humanities and Educational Advancements (EJHEA) Available Online at: https://www.scholarzest.com Vol. 2 No. 6, 2021 ISSN: 2660-5589 THE PROTRACTED CONFLICT IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND THE RESPONSE OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITIES Ikiri, Abraham Joe [email protected] 08037106716 Department of Political and Administrative Studies, University of Port-Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. Article history: Abstract: Received 26th April 2021 The Central African Republic has been embroiled in a protracted conflict since Accepted: 10th May 2021 1966 and is still raging with no possible hope yet in sight for its resolution. The Published: 6th June 2021 violent stage of the conflict is traced to the invasion of the country in 2012 by the Seleka armed militia group from the north of the country. This political instability resulted to the overthrow of President Francois Bozize and installation of a Moslem regime led by Michael Djolodia as President of the country. In retaliation and revenge to the outrageous killings, damage to properties and burning of communities targeted against the Christians/Animists in the south of the country by the Seleka, the anti-Balaka armed group was spontaneously formed to defend southern communities from further attacks. The conflict which was between the Seleka and the government army (FACA), has now spread to include the anti-Balaka, foreign fighters and international peace-keeper, all fighting against each other. It is against this backdrop that the article seek to analyze the conflict in that country and examine the reasons for the protraction of the conflict and interrogate the response strategies by the international community. -

Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Emergencies Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33498 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez. Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Emergencies SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................................= RECOMMENDATIONS ...............................................................................................................? ABANDONMENT AND OBSTACLES IN FLEEING ............................................................................;; ACCESS TO FOOD, SANITATION, AND MEDICAL SERVICES ..........................................................;> ACCESS TO EDUCATION