Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jmc-Pmay-B-Ews1 11-12-2020 5:44:33Pm

Result of Draw of Flat under PMAY Yojna JMC-PMAY-B-EWS1 Bedi Railway Overbridge, Jamnagar Date : 11-12-2020 5:44:33PM Sr. Appl. No. Name & Address Category Flat No. No. 1 B-EWS 1-206-443 FAFAL KHETIBEN TESHIBHAI SC Bedi/EWS1-A-106 BOMBE DAVA BAJAR COLONY,NAHERUNAGAR SERI NO.5 ANDHASHRAM PACHHAD,JAMNAGAR 2 B-EWS 1-206-88 PARMAR CHANDRAKANT DHULAB SC Bedi/EWS1-A-202 HARIKRIPA EPARTMENT-103,HIMMATNAGAR SERI NO.4,G.G. HOSPITAL NI PACHHAD 3 B-EWS 1-206-170 VAGHELA HANSHABEN NAVGHANB SC Bedi/EWS1-C-201 SARAKARI HIGH SCHOOL PACHHAD,HARIJAN VAS,UKABHAI VADA NA MAKAN MA, NAVAGAM GHED 4 B-EWS1-16/417 JOD SUSHILABEN BHARATBHAI SC Bedi/EWS1-A-406 MAYAR SAMAJ,VRUDDHASHRAM PASE,KHODIYAR COLONY,JAMNAGAR TRANSFER FROM R.S.16 5 B-EWS1-16/900 MUNRAI ABDUL GANI SC Bedi/EWS1-A-802 18-A,SIDI FALI,IKBAL CHOCK,BEDI,JAMNAGAR TRANSFER FROM R.S.16 6 B-EWS 1-206-409 DAFDA KHETIBEN RAMABHAI SC Bedi/EWS1-A-503 IQBAL CHOAK,BEDI,JAMNAGAR 7 B-EWS 1-206-14 MAKVANA AJAYKUMAR KAMLES SC Bedi/EWS1-A-801 SERI NO.6/4,VAISHALINAGAR,DHARAN AGAR-1,BEDESHAVAR ROAD 8 B-EWS 1-206-205 SHRIMALI ANUPAMA SUNIL SC Bedi/EWS1-C-401 DIGVIJAYGRAM,NIMAZ COLONY,KARABHUNGA VISATAR Printed on Date 11-12-2020 17:45:17 2819248139 Page 1 of 20 Result of Draw of Flat under PMAY Yojna JMC-PMAY-B-EWS1 Bedi Railway Overbridge, Jamnagar Date : 11-12-2020 5:44:33PM Sr. -

Economic and Revenue Sector for the Year Ended 31 March 2019

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Economic and Revenue Sector for the year ended 31 March 2019 GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT (Report No. 3 of the year 2020) http://www.cag.gov.in TABLE OF CONTENTS Particulars Paragraph Page Preface vii Overview ix - xvi PART – I Economic Sector CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION About this Report 1.1 1 Audited Entity Profile 1.2 1-2 Authority for Audit 1.3 3 Organisational structure of the Office of the 1.4 3 Principal Accountant General (Audit-II), Gujarat Planning and conduct of Audit 1.5 3-4 Significant audit observations 1.6 4-8 Response of the Government to Audit 1.7 8-9 CHAPTER II – COMPLIANCE AUDIT AGRICULTURE, FARMERS WELFARE AND CO-OPERATION DEPARTMENT Functioning of Junagadh Agricultural University 2.1 11-32 INDUSTRIES AND MINES DEPARTMENT Implementation of welfare programme for salt 2.2 32-54 workers FORESTS AND ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT Compensatory Afforestation 2.3 54-75 PART – II Revenue Sector CHAPTER–III: GENERAL Trend of revenue receipts 3.1 77 Analysis of arrears of revenue 3.2 80 i Arrears in assessments 3.3 81 Evasion of tax detected by the Department 3.4 81 Pendency of Refund Cases 3.5 82 Response of the Government / Departments 3.6 83 towards audit Audit Planning and Results of Audit 3.7 86 Coverage of this Report 3.8 86 CHAPTER–IV: GOODS AND SERVICES TAX/VALUE ADDED TAX/ SALES TAX Tax administration 4.1 87 Results of Audit 4.2 87 Audit of “Registration under GST” 4.3 88 Non/short levy of VAT due to misclassification 4.4 95 /application of incorrect rate of tax Irregularities -

Moorings: Indian Ocean Trade and the State in East Africa

MOORINGS: INDIAN OCEAN TRADE AND THE STATE IN EAST AFRICA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nidhi Mahajan August 2015 © 2015 Nidhi Mahajan MOORINGS: INDIAN OCEAN TRADE AND THE STATE IN EAST AFRICA Nidhi Mahajan, Ph. D. Cornell University 2015 Ever since the 1998 bombings of American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, especially post - 9/11 and the “War on Terror,” the Kenyan coast and the Indian Ocean beyond have become flashpoints for national and international security. The predominantly Muslim sailors, merchants, and residents of the coast, with transnational links to Somalia, the Middle East, and South Asia have increasingly become the object of suspicion. Governments and media alike assume that these longstanding transnational linkages, especially in the historical sailing vessel or dhow trade, are entwined with networks of terror. This study argues that these contemporary security concerns gesture to an anxiety over the coast’s long history of trade and social relations across the Indian Ocean and inland Africa. At the heart of these tensions are competing notions of sovereignty and territoriality, as sovereign nation-states attempt to regulate and control trades that have historically implicated polities that operated on a loose, shared, and layered notion of sovereignty and an “itinerant territoriality.” Based on over twenty-two months of archival and ethnographic research in Kenya and India, this dissertation examines state attempts to regulate Indian Ocean trade, and the manner in which participants in these trades maneuver regulatory regimes. -

Sr No Emp No. Name Department Name Designation Month Gross 1 15952 Ram Bilas A.B. Hostel Chowkidar Feb-21 48746 2 16078 Abhimanyu Prasad A.B

Sr No Emp No. Name Department Name Designation Month Gross 1 15952 Ram Bilas A.B. Hostel Chowkidar Feb-21 48746 2 16078 Abhimanyu Prasad A.B. Hostel Hostel Attendant Feb-21 48746 3 19392 Bharat Bhardwaj A.B. Hostel Hostel Attendant Feb-21 34220 4 20789 Jai Prakash Gupta A.B. Hostel MTS Feb-21 31819 5 16282 Mewa Lal Chauhan A.N.D. Hostel Hostel Attendant Feb-21 45033 6 17660 Chunnu Lal A.N.D. Hostel Chowkidar Feb-21 46256 7 19708 Pushyamitra Trivedi Academic Deputy Registrar Feb-21 112517 8 10204 R. K. Srivastava Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 71266 9 10206 V. K. Upadhyaya Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 73394 10 10480 Sanandan Singh Academic Section Officer Feb-21 73394 11 10900 Sanjeev Kumar Singh Academic Section Officer Feb-21 75522 12 17395 Saurabh Bhattacharya Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 69178 13 17396 Anita Kumari Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 69178 14 17399 Pandey Vishwanath Amarnath Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 71120 15 19361 Krishna Chandra Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 59916 16 19522 Pramod Kumar Academic Senior Assistant Feb-21 53724 17 20905 Ankita Kumari Academic Senior Clerk Feb-21 40198 18 10211 Guru Prasad Academic Peon Feb-21 56726 19 10213 Madan Mohan Jana Academic Peon Feb-21 48746 20 10215 Vinod Kumar Academic Peon Feb-21 48746 21 10651 Ratan Lal Academic Peon Feb-21 48746 22 12943 Himanshu Mishra Academic Cleaner Feb-21 48746 23 18929 Panna Lal Academic Peon Feb-21 37293 24 21483 Shiv Shankar Academic MTS Feb-21 30129 25 10391 D. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Amrita School of Art and Science Kochi

Amma signs Faith Leaders’ Universal Declaration Against Slavery at Vatican Amma joined Pope Francis in the Vatican and 11 other world religious leaders in a ceremonial signing of a declaration against human trafficking and slavery. Chancellor Amma Awarded Honorary Doctorate The State University of New York (SUNY) presented Amma with an honorary doctorate in humane letters at a special ceremony held on May 25, 2010 at Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall on the University at Buffalo North Campus. Amma Says...... When we study in college, striving to become a professional - this is education for a living. On the other hand, education for life requires understanding the essential principles of spirituality. This means gaining a My conviction is that deeper understanding of the world, our minds, our emotions, and ourselves. We all know that the real goal of science, technology and education is not to create people who can understand only the language of machines. The main purpose of spirituality must unite education should be to impart a culture of the heart - a culture based on spiritual values. in order to ensure Communication through machines has even made people in far off places seem very close. Yet, in the absence a sustainable and of communication between hearts, even those who are physically close to us seem to be far away. balanced existence of Today’s world needs people who express goodness in their words and deeds. If such noble role models set the our world. example for their fellow beings, the darkness prevailing in today’s society will be dispelled, and the light of peace - Amma and non-violence will once again illumine this earth. -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Goodman, Zoe (2018) Tales of the everyday city: geography and chronology in postcolonial Mombasa. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/30271 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Tales of the everyday city: geography and chronology in postcolonial Mombasa Zoë Goodman Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2017 Department of Anthropology and Sociology SOAS, University of London Abstract Grounded in ethnographic research conducted amongst Mombasa‘s small and heterogeneous Muslim population with roots in what is today the Indian state of Gujarat, this thesis explores the mobilities, insecurities, notions of Islamic reform and patterns of claims-making that circulate in the city. These themes are examined through the lens of ‗everyday‘ discourse and practice, paying particular attention to the multiplicity of dispositions towards time and space that inform these broader urban processes. The thesis describes Mombasan Muslims struggling with history and with the future. -

Former Rector, Darul Uloom Waqf, Deoband

Former Rector, Darul Uloom Waqf, Deoband Khatib alalal-al ---IslaIslaIslaIslamm MaMaMauMa uuullllaaaannnnaaaa MMMoMooohhhhammadammad Salim Qasmi R.A. Former Rector ofofof Darul Uloom Waqf Deoband Life Thoughts Contribution A compilation of papers presented in the “International seminar on Life and Achievements of Khatib al-Islam Maulana Mohammad Salim Qasmi R.A” Held on Sunday- Monday, 12 th -13 th August, 2018, at Darul Uloom Waqf Deoband Ḥujjat al-Isl ām Academy Darul Uloom Waqf, Deoband- 247554 Khatib al-Islam Maulana Mohammad Salim Qasmi R.A. Life Thoughts Contribution 1st Edition: 2019 ISBN: 978-93-84775-11-7 © Copyright 2019 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Published & Distributed by Hujjat al-Islam Academy Darul Uloom Waqf, Deoband, +91 1336 222 752 Website: www.dud.edu.in, Email: [email protected] Table of Contents I. Foreword 06 II. Report 15 III. Welcome Speech 100 IV. Chapter One: Life and Personality 106 o Maulana Salim R.A., The End of Golden Scholarly Era Mohammad Asjad Qasmi 107 o Khatib al-Islam Maulana Mohammad Salim Qasmi as a Great Speaker 1926-2018 Jaseemuddin Qasmi 129 o Maulana Mohammad Salim Qasmi: A Man of Courage and Conviction Dr. Atif Suhail Siddiqui 135 o Maulana Mohammad Salim Qasmi: Literary Style of Writing Dr. Saeed Anwar 141 o Hazrat Khatib al-Islam as a Lecturer Mohammad Javed Qasmi 152 o Hazrat Maulana Mohammad Salim Sahab Qasmi, The Orator Mohammad Asad Jalal Qasmi 162 V. -

The Musalman Races Found in Sindh

A SHORT SKETCH, HISTORICAL AND TRADITIONAL, OF THE MUSALMAN RACES FOUND IN SINDH, BALUCHISTAN AND AFGHANISTAN, THEIR GENEALOGICAL SUB-DIVISIONS AND SEPTS, TOGETHER WITH AN ETHNOLOGICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT, BY SHEIKH SADIK ALÍ SHER ALÍ, ANSÀRI, DEPUTY COLLECTOR IN SINDH. PRINTED AT THE COMMISSIONER’S PRESS. 1901. Reproduced By SANI HUSSAIN PANHWAR September 2010; The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 DEDICATION. To ROBERT GILES, Esquire, MA., OLE., Commissioner in Sindh, This Volume is dedicated, As a humble token of the most sincere feelings of esteem for his private worth and public services, And his most kind and liberal treatment OF THE MUSALMAN LANDHOLDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF SINDH, ВY HIS OLD SUBORDINATE, THE COMPILER. The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. In 1889, while I was Deputy Collector in the Frontier District of Upper Sindh, I was desired by B. Giles, Esquire, then Deputy Commissioner of that district, to prepare a Note on the Baloch and Birahoi tribes, showing their tribal connections and the feuds existing between their various branches, and other details. Accordingly, I prepared a Note on these two tribes and submitted it to him in May 1890. The Note was revised by me at the direction of C. E. S. Steele, Esquire, when he became Deputy Commissioner of the above district, and a copy of it was furnished to him. It was revised a third time in August 1895, and a copy was submitted to H. C. Mules, Esquire, after he took charge of the district, and at my request the revised Note was printed at the Commissioner-in-Sindh’s Press in 1896, and copies of it were supplied to all the District and Divisional officers. -

Networks, Labour and Migration Among Indian Muslim Artisans ECONOMIC EXPOSURES in ASIA

Networks, Labour and Migration among Indian Muslim Artisans ECONOMIC EXPOSURES IN ASIA Series Editor: Rebecca M. Empson, Department of Anthropology, UCL Economic change in Asia often exceeds received models and expecta- tions, leading to unexpected outcomes and experiences of rapid growth and sudden decline. This series seeks to capture this diversity. It places an emphasis on how people engage with volatility and flux as an omnipres- ent characteristic of life, and not necessarily as a passing phase. Shedding light on economic and political futures in the making, it also draws atten- tion to the diverse ethical projects and strategies that flourish in such spaces of change. The series publishes monographs and edited volumes that engage from a theoretical perspective with this new era of economic flux, exploring how current transformations come to shape and are being shaped by people in particular ways. Networks, Labour and Migration among Indian Muslim Artisans Thomas Chambers First published in 2020 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Thomas Chambers, 2020 Images © Thomas Chambers, 2020 Thomas Chambers has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work, to adapt the work, and to make commercial use of the work, provided attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). -

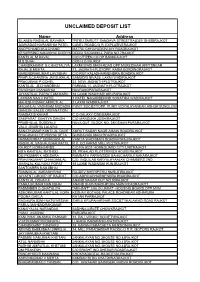

Unclaimed Deposit List

UNCLAIMED DEPOSIT LIST Name Address SILABEN RASIKLAL BAVARIA "PITRU SMRUTI" SANGAVA STREETRAJDEV SHERIRAJKOT JAMNADAS NARANBHAI PATEL CANEL ROADC/O R. EXPLASIVERAJKOT ANOPCHAND MULCHAND MATRU CHHAYADIGVIJAY ROADRAJKOT KESARISING NANJIBHAI DODIYA DODIA SADANMILL PARA NO.7RAJKOT KANTILAL M RAVAL C/O CITIZEN CO.OP.BANKRAJKOT M S SHAH CCB.H.O.RAJKOT CHANDRAKANT G CHHOTALIYA LAXMI WADI MAIN ROAD OPP MURLIDHAR APPTSNEAR RAJAL B MEHTA 13, JAGNATH PLOTOPP. KADIA BORDINGRAJKOT NARENDRAKUMAR LAVJIBHAI C/O RUP KALADHARMENDRA ROADRAJKOT PRAFULCHANDRA JAYSUKHLAL SAMUDRI NIVAS5, LAXMI WADIRAJKOT PRAGJIBHAI P GOHEL 22. NEW JAGNATH PLOTRAJKOT KANTILAL JECHANDBHAI PARIMAL11, JAGNATH PLOTRAJKOT RAYDHAN CHANABHAI NAVRANGPARARAJKOT JAYANTILAL PARSOTAM MARU 18 LAXMI WADIHARI KRUPARAJKOT LAXMAN NAGJI PATEL 1 PATEL NAGARBEHIND SORATHIA WADIRAJKOT MAHESHKUMAR AMRUTLAL 2 LAXMI WADIRAJKOT MAGANLAL VASHRAM MODASIA PUNIT SOCIETYOPP. PUNIT VIDYALAYANEAR ASHOK BUNGLOW GANESH SALES ORGANATION RAMDAS B KAHAR C.O GALAXY CINEMARAJKOT SAMPARAT SAHITYA SANGH C/O MANSUKH JOSHIRAJKOT PRABHULAL BUDDHAJI NAVA QUT. BLOCK NO. 28KISHAN PARARAJKOT VALJI JIVABHIA LALKIYA SANATKUMAR KANTILAL DAVE AMRUT SADAR NAGR AMAIN ROADRAJKOT BHAGWANJI DEVSIBHAI SETA GUNDAVADI MAIN ROADRAJKOT HASMUKHRAY CHHAGANLAL VANIYA WADI MAIN ROADNATRAJRAJKOT RASIKLAL VAGHAJIBHAI PATEL R.K. CO.KAPAD MILL PLOTRAJKOT RAJKOT HOMEGARDS C/O RAJKOT HOMEGUARD CITY UNITRAJKOT NITA KANTILAL RATHOD 29, PRHALAD PLOTTRIVEDI HOUSERAJKOT DILIPKUMAR K ADESARA RAMNATH PARAINSIDE BAHUCHARAJI NAKARAJKOT PRAVINKUMAR CHHAGANLAL -

Pakistan – Tehreek-E-Nafaz-E-Shariat-E-Mohammadi (TNSM) – Maulana Fazalullah – Forced Recruitment – Recruitment of Youths – Internal Relocation – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PAK32205 Country: Pakistan Date: 29 August 2007 Keywords: Pakistan – Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM) – Maulana Fazalullah – Forced recruitment – Recruitment of youths – Internal relocation – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please advise whether Fazul Ullah is a cleric and is the leader of an extremist group? 2. How powerful is this group and is it their usual practice to recruit young boys from villages? 3. How far does the influence of this group extend throughout Pakistan? 4. What attempts, if any, have the Pakistani authorities made to enforce the law against this group and how successful have they been to date? RESPONSE 1. Please advise whether Fazul Ullah is a cleric and is the leader of an extremist group? 4. What attempts, if any, have the Pakistani authorities made to enforce the law against this group and how successful have they been to date? Introduction A cleric known as Fazalullah (also: Fazul Ullah or Fazal-ullah or Fazlullah) is widely reported to be the acting leader and senior cleric of Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM; or Movement for the Enforcement of Islamic Laws).