Health Effects of Artificial Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Spectroscopic Toolbox

13 1 The Spectroscopic Toolbox 1.1 Introduction Present spectroscopic instruments use essentially bulk optics, that is, with sizes much greater than the wavelengths at which the instruments are used (0.3–2.4 μm in this book). Diffraction effects – due to the finite size of light wavelength – are then usually negligible and light propagation follows the simple precepts of geometrical optics. A special case is the disperser or interferometer that provides the spectral information: these are also large size optical devices (say 5 cm to 1 m across), but which exhibit periodic structures commensurate with the working wavelengths. The next subsection gives a short reminder of geometrical optics formulae that dictate how light beams propagate in bulk optical systems. It is followed by an introduction of a fundamental global invariant (the optical etendue) that governs the 4D geometrical extent of the light beams that any kind of optical system can accept: it is particularly useful to derive what an instrument can – and cannot – offer in terms of 3D coverage (2D of space and 1 of wavelength). 1.1.1 Geometrical Optics #101 As a short reminder of geometrical optics, that is, again the rules that apply to light propagation when all optical elements (lenses, mirrors, stops) have no fea- tures at scales comparable or smaller than light wavelength are listed: 1) Light beams propagate in straight lines in any homogeneous medium (spa- tially constant index of refraction n). 2) When a beam of light crosses from a dielectric medium of index of refraction n1 (e.g., air with n close to 1) to another dielectric of refractive index n2 (e.g., an optical glass with refractive index roughly in the 1.5–1.75 range), part of the beam is transmitted (refracted) and the remainder is reflected. -

Astronomical Instrumentation G

Astronomical Instrumentation G. H. Rieke Contents: 0. Preface 1. Introduction, radiometry, basic optics 2. The telescope 3. Detectors 4. Imagers, astrometry 5. Photometry, polarimetry 6. Spectroscopy 7. Adaptive optics, coronagraphy 8. Submillimeter and radio 9. Interferometry, aperture synthesis 10. X-ray instrumentation Introduction Preface Progress in astronomy is fueled by new technical opportunities (Harwit, 1984). For a long time, steady and overall spectacular advances were made in telescopes and, more recently, in detectors for the optical. In the last 60 years, continued progress has been fueled by opening new spectral windows: radio, X-ray, infrared, gamma ray. We haven't run out of possibilities: submillimeter, hard X-ray/gamma ray, cold IR telescopes, multi-conjugate adaptive optics, neutrinos, and gravitational waves are some of the remaining frontiers. To stay at the forefront requires that you be knowledgeable about new technical possibilities. You will also need to maintain a broad perspective, an increasingly difficult challenge with the ongoing explosion of information. Much of the future progress in astronomy will come from combining insights in different spectral regions. Astronomy has become panchromatic. This is behind much of the push for Virtual Observatories and the development of data archives of many kinds. To make optimum use of all this information requires you to understand the capabilities and limitations of a broad range of instruments so you know the strengths and limitations of the data you are working with. As Harwit (1984) shows, before ~ 1950, discoveries were driven by other factors as much as by technology, but since then technology has had a discovery shelf life of only about 5 years! Most of the physics we use is more than 50 years old, and a lot of it is more than 100 years old. -

Article Soot Photometer Using Supervised Machine Learning

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 3885–3906, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-3885-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Classification of iron oxide aerosols by a single particle soot photometer using supervised machine learning Kara D. Lamb1,2 1Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Chemical Sciences Division, Boulder, CO, USA Correspondence: Kara D. Lamb ([email protected]) Received: 15 March 2019 – Discussion started: 22 March 2019 Revised: 20 June 2019 – Accepted: 21 June 2019 – Published: 15 July 2019 Abstract. Single particle soot photometers (SP2) use laser- each class are compared with the true class for those particles induced incandescence to detect aerosols on a single particle to estimate generalization performance. While the specific basis. SP2s that have been modified to provide greater spec- class approach performed well for rBC and Fe3O4 (≥ 99 % tral contrast between their narrow and broad-band incandes- of these aerosols are correctly identified), its classification of cent detectors have previously been used to characterize both other aerosol types is significantly worse (only 47 %–66 % refractory black carbon (rBC) and light-absorbing metallic of other particles are correctly identified). Using the broader aerosols, including iron oxides (FeOx). However, single par- class approach, we find a classification accuracy of 99 % for ticles cannot be unambiguously identified from their incan- FeOx samples measured in the laboratory. The method al- descent peak height (a function of particle mass) and color lows for classification of FeOx as anthropogenic or dust-like ratio (a measure of blackbody temperature) alone. -

LED Retrofit Headlamp Light Sources Ensure Legal Access to the German Automotive Market

LED Retrofit Headlamp Light Sources Ensure legal access to the German automotive market Your challenges Before September 2020, the Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt hazards. Other advantages include: (Federal Motor Transport Authority) did not permit the ■ Near-daylight luminescence for improved visibility replacement of vehicle headlamps with LED retrofit ■ Quicker response time to 100% light light sources for driving beams and passing beams in ■ Highly resistant to vibration and shock Germany, as the appropriate homologation guidelines did ■ Longer lifetime not exist. Consequently, vehicle owners could not modify ■ Higher efficiency (lm/W), fewer CO2 emissions and their old halogen lamps with LEDs and manufacturers more environmentally friendly were unable to sell LED retrofits for vehicles registered on German public roads. Why is retrofitted LED headlamp light source testing and compliance important? The advantages of headlamps equipped with All external light sources on a vehicle, such as headlights or LED retrofit brake lights, are considered “technical lighting equipment” According to a study by the Allgemeiner Deutscher and must be type approved. Any subsequent modifications Automobil-Club (ADAC), retrofitting car headlights with to the type-approved lighting equipment will have an impact LEDs offers a road traffic safety gain. This is because on the type approval of the entire vehicle, and result in the retrofitted LED headlights are more durable, have a longer loss of the operating licence for public roads. beam range and their white light improves contrast. It is therefore essential that any LED updates made to Overall, LEDs have been proven to increase driver safety headlamps are installed correctly, do not disadvantage through improved visibility and earlier detection of road other road users and meet current safety requirements. -

Introduction 1

1 1 Introduction . ex arte calcinati, et illuminato aeri [ . properly calcinated, and illuminated seu solis radiis, seu fl ammae either by sunlight or fl ames, they conceive fulgoribus expositi, lucem inde sine light from themselves without heat; . ] calore concipiunt in sese; . Licetus, 1640 (about the Bologna stone) 1.1 What Is Luminescence? The word luminescence, which comes from the Latin (lumen = light) was fi rst introduced as luminescenz by the physicist and science historian Eilhardt Wiede- mann in 1888, to describe “ all those phenomena of light which are not solely conditioned by the rise in temperature,” as opposed to incandescence. Lumines- cence is often considered as cold light whereas incandescence is hot light. Luminescence is more precisely defi ned as follows: spontaneous emission of radia- tion from an electronically excited species or from a vibrationally excited species not in thermal equilibrium with its environment. 1) The various types of lumines- cence are classifi ed according to the mode of excitation (see Table 1.1 ). Luminescent compounds can be of very different kinds: • Organic compounds : aromatic hydrocarbons (naphthalene, anthracene, phenan- threne, pyrene, perylene, porphyrins, phtalocyanins, etc.) and derivatives, dyes (fl uorescein, rhodamines, coumarins, oxazines), polyenes, diphenylpolyenes, some amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine), etc. + 3 + 3 + • Inorganic compounds : uranyl ion (UO 2 ), lanthanide ions (e.g., Eu , Tb ), doped glasses (e.g., with Nd, Mn, Ce, Sn, Cu, Ag), crystals (ZnS, CdS, ZnSe, CdSe, 3 + GaS, GaP, Al 2 O3 /Cr (ruby)), semiconductor nanocrystals (e.g., CdSe), metal clusters, carbon nanotubes and some fullerenes, etc. 1) Braslavsky , S. et al . ( 2007 ) Glossary of terms used in photochemistry , Pure Appl. -

Optics Microstructured Optics SMS Design Methods Plastic Optics

www.led-professional.com ISSN 1993-890X Review LpR The technology of tomorrow for general lighting applications. Sept/Oct 2008 | Issue 09 Optics Microstructured Optics SMS Design Methods Plastic Optics LED Driver Circuits Display Report Copyright © 2008 Luger Research & LED-professional. All rights reserved. There are over 20 billion light fixtures using incandescent, halogen, Design of LED or fluorescent lamps worldwide. Many of these fixtures are used for directional light applications but are based on lamps that put Optics out light in all directions. The United States Department of Energy (DOE) states that recessed downlights are the most common installed luminaire type in new residential construction. In addition, the DOE reports that downlights using non-reflector lamps are typically only 50% efficient, meaning half the light produced by the lamp is wasted inside the fixture. In contrast, lighting-class LEDs offer efficient, directional light that lasts at least 50,000 hours. Indoor luminaires designed to take advantage of all the benefits of lighting-class LEDs can exceed the efficacy of any incandescent and halogen luminaire. Furthermore, these LEDs match the performance of even the best CFL (compact fluorescent) recessed downlights, while providing a lifetime five to fifty times longer before requiring maintenance. Lastly, this class of LEDs reduces the environmental impact of light (i.e. no mercury, less power-plant pollution, and less landfill waste). Classical LED optics is composed of primary a optics for collimation and a secondary optics, which produces the required irradiance distribution. Efficient elements for primary optics are concentrators, either using total internal reflection or combined refractive/reflective versions. -

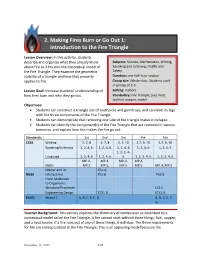

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle. -

Comparison of Colorimetric, Fluorescence and Luminescence Analysis

www.aladdin-e.com Comparison of colorimetric, fluorescence and luminescence analysis Introduction 25°C, and 37°C, Over the years, the enzyme immunoassay that greater than six months shelf life when stored Engvall and Perlmann first described has taken at 4°C, many different forms. Today there are commercially available, heterogeneous, homogeneous, cell-based, capable of being conjugated to an antigen or colorimetric, fluorescent and luminescent, to antibody, name just a few, versions of the original ELISA. inexpensive, They all have antibody-antigen complexes and easily measurable activity, enzyme reactions in common. In this technical high substrate turnover number, bulletin, we here will focus on the enzyme linked unaffected by biological components of the immunosorbent assay and discuss three types of assay. detection systems — colorimetric, fluorescent, and luminescent. By far, the two most popular enzymes are All ELISA, regardless of the detection system peroxidase and alkaline phosphatase. Each has employed, require the immobilization of an their advantages and disadvantages. Both are antigen or antibody to a surface. They also quite stable when handled and stored properly, require the use of an appropriate enzyme label and both can be stored at 4°C for greater than 6 and a matching substrate that is suitable for the months. Both are also commercially available as detection system being used. Associated with the free enzymes and as enzyme conjugates (enzyme enzyme-substrate reaction are several labeled antibodies, etc.) and are relatively requirements, such as timing and development inexpensive. However, there are some differences conditions, that need to be optimized to result in between these two enzymes that should be a precise, accurate and reproducible assay. -

Dermatopathology

Dermatopathology Clay Cockerell • Martin C. Mihm Jr. • Brian J. Hall Cary Chisholm • Chad Jessup • Margaret Merola With contributions from: Jerad M. Gardner • Talley Whang Dermatopathology Clinicopathological Correlations Clay Cockerell Cary Chisholm Department of Dermatology Department of Pathology and Dermatopathology University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Central Texas Pathology Laboratory Dallas , TX Waco , TX USA USA Martin C. Mihm Jr. Chad Jessup Department of Dermatology Department of Dermatology Brigham and Women’s Hospital Tufts Medical Center Boston , MA Boston , MA USA USA Brian J. Hall Margaret Merola Department of Dermatology Department of Pathology University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Brigham and Women’s Hospital Dallas , TX Boston , MA USA USA With contributions from: Jerad M. Gardner Talley Whang Department of Pathology and Dermatology Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Boston, MA Little Rock, AR USA USA ISBN 978-1-4471-5447-1 ISBN 978-1-4471-5448-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4471-5448-8 Springer London Heidelberg New York Dordrecht Library of Congress Control Number: 2013956345 © Springer-Verlag London 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

Ambient Lightand Sleep in Community Dwelling Older

AMBIENT LIGHT AND SLEEP IN COMMUNITY DWELLING OLDER ADULTS By ASHLEY MAE STRIPLING A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Ashley Mae Stripling 2 To all who light up life 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my chair Dr. Christina McCrae for her intellectual guidance and constant mentoring; my supervisory committee members for their time and recommendations; the Sleep Research Lab for their support, Amanda Ross, Natalie Dautovich, Joseph MacNamara, and Joseph Dzierzewski; my parents, Richard and Rozann Stripling for their unconditional love and unvarying support through my entire educational process; and Rome Cagnina for editing countless copies of this work. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................................. 8 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 11 REVIEW -

Visual Timing Light Biodynamic Light in Elderly Care 2 3

VISUAL TIMING LIGHT BIODYNAMIC LIGHT IN ELDERLY CARE 2 3 CONTENTS VISUAL TIMING LIGHT PAGE MAN AND LIGHT 4 NATURE AS A MODEL 6 THE THIRD DIMENSION OF LIGHT 8 THE INTERNAL CLOCK 10 BIOLOGICALLY EFFECTIVE LIGHT 12 VISUAL TIMING LIGHT (VTL) SENIORS 14 BETTER LIGHTING FOR THE ELDERLY 16 DEMENTIA ADDED VALUE 18 ADVANTAGES FOR RESIDENTS ”All the variety, all the charm, 20 ADVANTAGES FOR CAREGIVERS all the beauty of life are made 22 BENEFITS FOR OPERATORS AND HOME MANAGERS up of light and shade” Leo N. Tolstoy, ”Anna Karenina” VTL-SYSTEM 24 THE LIGHT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM VTL 26 THE VTL-COMPONENTS / Shaun Lowe ® iStockphoto 4 5 NATURE AS A MODEL AND A LITTLE BIT BETTER Light is everything in nature. It provides growth, diversity and beauty. We humans are a part of nature. Light is therefore the most natural nourishment in the world for us. It determines our entire existence: Light affects important hormonal and metabolic processes, synchronizing our internal clocks again and again. Light gives our lives rhythm. Whenever there is a lack of natural daylight our rhythm is disrupted. The Visual Timing Light (VTL) system from Derungs recreates the effects of natural daylight, restoring proper rhythm and balance to people’s lives. / konradlew / ® iStockphoto 6 7 MARVEL OF NATURE THE THIRD DIMENSION OF LIGHT It is well known that the benefits of light go beyond just helping us see and creating a pleasant atmosphere within a space. Now, scientific research has shown that natural light also positively affects our biological health and well-being. These findings have created the third biological dimension of light. -

Rare Skin Diseases: Treatment and Diagnosis

erimenta xp l D E e r & m l a a t c o i l n o i l g y C Journal of Clinical & Experimental f R o e l ISSN: 2155-9554 s a e n a r r u c o h J Dermatology Research Short Communication Rare Skin Diseases: Treatment and Diagnosis Kenneth Jones* Department of Dermatology, University of Malaga, Malaga, Spain ABSTRACT A skin disease, also known as cutaneous condition, is any medical condition that affects the integumentary system- the organ system that encloses the body and involves skin, hair, nails, and associated muscle and glands. The main feature of this device is as a buffer against the external world. Skin disease, any of the diseases or disorders that affect the human skin. They have a wide range of cause’s skin rash caused by Lyme disease rashes and hives, for example, are visible changes in the texture of the skin that may indicate a severe disease. Keywords: Skin; Blau syndrome; Argyria; Diagnosis DESCRIPTION protect the organism. Overexpression appears to be the result of a genetic mutation in BS [1]. The skin is the largest organ of the human body. There are a number of conditions that can affect the skin. Some of them are Treatment: Treatment has included the usual anti-inflammatory common, while others are rare. Many people may have drugs such as adrenal glucocorticoids, anti-metabolites and also experienced eczema or hives, for instance. However, some skin biological agents such as anti-TNF and infliximab all with diseases affect far fewer people.