Maks Samec and His Adapting to Academic Standards After World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Controversy on Photons and the Hanbury-Brown & Twiss Experiment

The Controversy on Photons and the Hanbury-Brown & Twiss Experiment Indianara Lima Silva Universidade Federal da Bahia Abstract: One can think that the hypothesis of existence of the photons was established through the experimental results carried out by Robert A. Millikan (1868- 1953), who confirmed the Einstein's equation of the photoelectric effect in 1915, and by Arthur H. Compton (1892-1962), who showed that for explaining the X-rays scattering by matter it was necessary to consider the corpuscular nature of radiation in 1923. Nevertheless, the history of the photon concept is not as linear as it may seem. Throughout the twentieth century, the demand for the concept of photon was challenged at least by the following physicists: Guido Beck (1903-1988) in his paper Zur Theorie des Photoeffekts published in 1927, Erwin Schrödinger (1887-1961) in Über den Comptoneffect published in 1927, Gregor Wentzel (1898-1978) in Zur Theorie des photoelektrisohen Effekts published also in 1927, John Newton Dodd (1922-2005) in The Compton effect – a classical treatment published in 1983, Janez Strnad (1934 – ) in The Compton effect – Schrodinger’s treatment published in 1986, Willis Eugene Lamb (1913-2008) and Marlan 0rvil Scully (1939 – ) in The Photoelectric Effect Without Photons of 1969, and again by Lamb in his paper Anti-photon published in 1995. On the other hand, never before the need of such a concept was felt as in current times. For instance, The International Society for Optical Engineering has organized conferences since 2003 whose interests is already described in their title, The Nature of Light: What is the Photon? According to the editors of the 2005 conference, “We all know that for centuries light has been playing a crucial role in the evolution of both sciences and technologies and the field is becoming ever more important every day” (Roychoudhuri, Creath and Kracklauer, p. -

Experimental Verification of the Zero-Point Energy of Electromagnetic Waves in the Quantum-Vacuum

Experimental Verification of the Zero-point Energy of Electromagnetic waves in the Quantum-vacuum PACS-classification: 84.60.-h, 89.30.-g, 98.62.En, 12.20.-m, 12.20.Ds, 12.20.Fv by Claus Wilhelm Turtur Germany, Wolfenbüttel, August – 24 – 2011 Adress of the Author: Prof. Dr. Claus W. Turtur University of Applied Sciences Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel Salzdahlumer Straße 46/48 Germany - 38302 Wolfenbüttel Tel.: (++49) 5331 / 939 - 42220 Email.: [email protected] Internet-page: http://www.ostfalia.de/cms/de/pws/turtur/FundE/index.html Table of Contents 1. Introduction...........................................................................................................................2 2. Philosophical background.....................................................................................................3 2.1. Static fields versus Theory of Relativity ........................................................................3 2.2. A circulation of energy of the electrostatic field ..........................................................10 2.3. A circulation of energy of the magnetostatic field .......................................................14 3. Theoretical fundament of the energy-flux...........................................................................20 3.1. Vacuum-energy in Quantum mechanics.......................................................................20 3.2. Connection with the classical model of vacuum-energy..............................................22 3.3. New microscopic model for the electromagnetic -

A Lecture on Nuclear Physics in Primary School

International Conference Nuclear Energy for New Europe 2004 Portorož • Slovenia • September 6-9 [email protected] www.drustvo-js.si/port2004 +386 1 588 5247, fax +386 1 561 2276 PORT2004, Nuclear Society of Slovenia, Jamova 39, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia A Lecture on Nuclear Physics in Primary School Stane Arh Medvode Primary School Ostrovrharjeva 4, SI-1215 Medvode, Slovenia [email protected] ABSTRACT I am going to propose the contents of a lecture on nuclear physics and radioactivity in primary school. Contemporary technology, medicine and science exploit intensively the discovered knowledge about processes in atoms and in a nucleus. Mankind has gained huge profit from peaceful applications of nuclear reactions and ionizing radiation. We use the products of nuclear industry every day. But about half of the school population never hears a professional explanation about what is going on in nuclear power plants. Only on some secondary schools students learn about nuclear physics. The lack of knowledge about nuclear processes is the main reason why people show great fear when hearing the words: radiation, radioactivity, nuclear, etc. At last it is now time to give some fundamental lessons on nuclear physics and radioactivity also to pupils in primary school. From my four-year teaching experience in primary school I am suggesting a programme of lectures on nuclear physics and radioactivity. At the end of the lessons we would visit the Krško Nuclear Power Plant or the Nuclear Training Centre Milan Čopič. This could be included in the so called natural science day. Pupils come from the eight class (14 years old) of primary school and have no problems following the explanation. -

Jožef Stefan, Master of Transport Phenomena

JOŽEF STEFAN MASTER OF TRANSPORT PHENOMENA I J. Strnad - Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenija - DOI: 10.1051/epn/2011201 Jožef Stefan is famous primarily for the Stefan-Boltzmann radiation law. But this remarkable physicist made original contributions in all fields of physics: fluid flow, mechanical oscillations, polarization of light, double refraction, interference and wavelength measurements. He also measured the heat conductivity of gases. He was among the few physicists who promoted Maxwell's electrodynamics theory. n Stefan's life there are two distinct periods. gymnasium and in 1853 he went to the University of ᭡ Jožef stefan During the first Stefan followed many interests Vienna to study mathematics and physics. In his youth he (1835-1893) including literature, whilst the second was devoted loved to sing and took part in choirs which he also organi - I entirely to physics. Stefan was a Slovenian who zed. Under the tutorship of his teacher and together with achieved his scientific successes in Vienna as a citizen of his schoolmates he founded a hand-written Slovenian Austria (aer 1867 Austria-Hungary). literary journal. He wrote poems for it, which were later Jožef Stefan (Fig. 1) was born on March 24, 1835 at St. published in Slovenian journals appearing in Austria. He Peter, nowadays part of Celovec (Klagenfurt) [1]-[5]. His did not overestimate the value of his poems, but he could teachers soon noticed his talents. In 1845 he entered the well have become a Slovenian poet had he not chosen ᭤ Article available at http://www.europhysicsnews.org or http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/epn/2011201 EPN 42/2 17 History JoŽEf stEfaN ᭤ fig. -

Simplifications and Idealizations in High School Physics in Mechanics: a Study of Slovenian Curriculum and Textbooks

European J of Physics Education Volume 5 Issue 3 2014 Forjan & Slisko Simplifications and Idealizations in High School Physics in Mechanics: A Study Of Slovenian Curriculum And Textbooks Matej Forjan School Centre Novo mesto, Šegova 112, SI-8000 Novo mesto, Slovenia Faculty of Industrial Engineering, Šegova 112, SI-8000 Novo mesto, Slovenia [email protected] Josip Sliško Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla Abstract This article presents the results of an analysis of three Slovenian textbooks for high school physics, from the point of view of simplifications and idealizations in the field of mechanics. In modeling of physical systems, making simplifications and idealizations is important, since one ignores minor effects and focuses on the most important characteristics of the systems and processes. In high school physics, simplified and idealized models play a fundamental role in learning physics concepts and laws, so it is of crucial importance that textbooks present them carefully. The review shows that in two textbooks more than a half of analyzed simplifications are not properly presented. Keywords: Physics curriculum, textbook analysis, simplified models, idealizations Introduction Research in recent years and decades shows that science subjects in general and physics in particular are becoming less popular and interesting for students (Osborne, Simon and Collins, 2003; Osborne and Collins, 2008; Osborne and Dillon, 2008; Haste, 2012; Saleh, 2012). One of the main reasons for students’ negative attitude is the fact that in school physics teachers are dealing with topics that are quite distant from the student's reality and, as such, are neither relevant to their daily lives nor relevant to the most pressing problems of mankind (Osborne and Dillon, 2008; Zhu and Singh, 2013). -

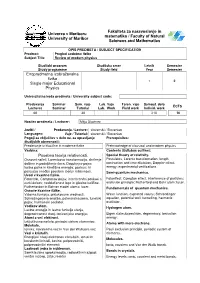

Pregled Sodobne Fizike Subject Title: Review of Modern Physics

Fakulteta za naravoslovje in Univerza v Mariboru matematiko / Faculty of Natural University of Maribor Sciences and Mathematics OPIS PREDMETA / SUBJECT SPECIFICATION Predmet: Pregled sodobne fizike Subject Title: Review of modern physics Študijski program Študijska smer Letnik Semester Study programme Study field Year Semester Enopredmetna izobraževalna fizika 1 2 Single major Educational Physics Univerzitetna koda predmeta / University subject code: Predavanja Seminar Sem. vaje Lab. Vaje Teren. vaje Samost. delo ECTS Lectures Seminar Tutorial Lab. Work Field work Individ. work 60 30 210 10 Nosilec predmeta / Lecturer: Mitja Slavinec Jeziki / Predavanja / Lecture: slovenski / Slovenian Languages: Vaje / Tutorial: slovenski / Slovenian Pogoji za vključitev v delo oz. za opravljanje Prerequisites: študijskih obveznosti: Predznanje iz klasične in moderne fizike Preknowledge of classical and modern physics Vsebina: Contents (Syllabus outline): Posebna teorija relativnosti. Special theory of relativity. Osnovni načeli, Lorentzova transformacija, skrčenje Postulates, Lorentz transformation, length dolžine in podaljšanje časa, Dopplerjev pojav, contraction and time dilatation, Doppler effect; lastna polna in kinetična energija; poskusi, ki energy; experimental verifications č potrjujejo ena be posebne teorije relativnosti. Semi-quantum mechanics. Uvod v kvantno fiziko. Fotoefekt, Comptonov pojav, interferenčni poskusi s Fotoeffect, Compton effect, interference of particles; curki delcev; nedoločenost lege in gibalne količine, exclusion principle; -

Putting the Quantum to Work: Otto Sackur's Pioneering Exploits in The

Putting the quantum to work: Otto Sackur’s pioneering exploits in the quantum theory of gases Massimiliano Badino and Bretislav Friedrich FHI Abstract: In the wake of the First Solvay Conference (1911), many leading physicists had begun embracing the quantum hypothesis as a key to solving outstanding problems in the theory of matter. The quantum approach proved successful in tackling the solid state, resulting in the nearly definitive theories of Debye (1912) and of Born & von Karman (1912-13). However, the application of the old quantum theory to gases was hindered by serious difficulties, which were due to a lack of a straightforward way of reconciling the frequency-dependent quantum hypothesis with the aperiodic behavior of gas molecules. A breakthrough came from unlikely quarters. Otto Sackur (1880-1914) had been trained as a physical chemist and had almost no experience in the research fields traditionally associated with quantum theory (heat radiation, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics). However, in 1911, he discovered an expression for the absolute entropy of a monoatomic gas. A Dutch high-school student, Hugo Martin Tetrode, reached the same result at about the same time independently. The Sackur-Tetrode equation rendered entropy as an extensive variable (in contrast to the classical expression, cf. the Gibbs paradox) and expressed the thermodynamically undetermined constant in terms of molecular parameters and Boltzmann’s and Planck’s constants. This result was of great heuristic value because it suggested the possibility of deriving the thermodynamic variables of a gas quantum mechanically. At the same time, the Sackur-Tetrode equation offered a conventient means to evaluate the parameters of molecular gases, thus promising a grand unification of quantum theory, thermodynamics, and physical chemistry. -

Nobelova Nagrada Za Fiziko Podeljena Za Odkritje Nevtrinskih Oscilacij ■

december 2015, 4/78. letnik cena v redni prodaji 5,50 EUR naročniki 4,50 EUR upokojenci 3,70 EUR dijaki in študenti 3,50 EUR www.proteus.si ■ Nobelove nagrade za leto 2015 Nobelova nagrada za fiziko podeljena za odkritje nevtrinskih oscilacij ■ V spomin Janez Strnad (4. marca 1934 - 28. novembra 2015) ■ Farmacija Fitoestrogeni in možnosti njihove uporabe ■ Naravoslovna fotografija Rezultati natečaja naravoslovne fotografije za leto 2015 Vsebina 147 153 177 170 ■ stran 150 Nobelove nagrade za leto 2015 Nobelova nagrada za fiziko podeljena za 148 Uvodnik 170 Medicina odkritje nevtrinskih oscilacij Tomaž Sajovic Puščanje krvi - od venesekcije do pijavk Jurij Kurillo Janez Strnad 150 Nobelove nagrade za leto 2015 Nobelova nagrada za fiziko podeljena za 177 Naravoslovna fotografija Letošnjo Nobelovo nagrado za fiziko sta si razdelila Takaaki Kadžita in Arthur B. McDo- odkritje nevtrinskih oscilacij Rezultati natečaja naravoslovne fotografije nald za »odkritje nevtrinskih oscilacij, ki kažejo, da imajo nevtrini maso«. Nagrajenca vodi- Janez Strnad za leto 2015 ta veliki raziskovalni skupini, Kadžita japonsko Superkamiokande, McDonald pa kanadski Petra Draškovič Pelc Nevtrinski observatorij Sudbury. Nevtrinske oscilacije so jasno znamenje, da imajo nevtrini 153 V spomin majhno maso. To pomeni, da bo zagotovo treba spremeniti standardni model delcev, saj je Janez Strnad (4. marca 1934 - 28. 185 Drobne vesti ta predvideval, da imajo nevtrini maso nič. Zdaj je treba raziskovati modele in izbirati naj- novembra 2015) Jože Bole – ob dvajseti obletnici smrti boljše. Dosedanji predlogi kažejo prve uspehe. Aleš Mohorič Rajko Slapnik Prispevek je zadnje besedilo, ki ga je pokojni prof. dr. Janez Strnad pripravil za objavo v 156 Farmacija 185 Naše nebo reviji Proteus. -

Abstract Book

3rd International GIREP Seminar »Informal learning and Public Understanding of Physics« 5 – 9 September 2005, Ljubljana, Slovenia Organized by: Groupe International sur l’Enseignement de la Physique (GIREP) European Physical Society (EPS) Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, University of Ljubljana Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana The House of Experiments, Ljubljana with the support of: Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) People in charge Gorazd Planinšič (University of Ljubljana) Mojca Čepič (University of Ljubljana) Miha Kos (The House of Experiments) Book of abstracts 1 International Advisory Board Michele D’Anna, Ped. Inst. for Teacher Edu, Locarno, Switzerland Ton Ellermeijer, Amsterdam University, Netherlands Manfred Euler, University of Kiel, Germany Nils Hornstrup, Experimentarium, Denmark Marjan Hribar, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Stanley Micklavzina, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA Kerry Parker, Auckland Girls’ Grammar School, New Zealand Michaele Renvillard, ECSITE, Belgium Rosa Maria Sperandeo, University of Palermo, Italy Gunnar Tibell, Uppsala University, Sweden Urbaan M Titulaer, Johannes Keppler University, Linz, Austria Christian Ucke, Tech. University Muenchen, Germany International Organizing Committee Nils Hornstrup, Experimentarium, Denmark Rajka Jurdana Šepić, University of Rijeka, Croatia Robert Lambourne, Open University, UK Leopold Matelitsch, University of Graz, Austria Zofia Mayer Golob, Krakow University, Poland Marisa Michelini, University of Udine, Italy Josip Slisko, Autonomous University of Puebla, Mexico David Sokoloff, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA Michael Vollmer, University of Appl. Sci, Brandenburg, Germany Richard Walton, Sheffield Hallam University, UK Local Organizing Committee Gorazd Planinšič, Faculty for Mathematics and Physics, University of Ljubljana (Chairman) Mojca Čepič, Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana (Co-chairman) Miha Kos, The House of Experiments, Slovenian science centre (Co-chairman) Jure Bajc, Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana Marko Budiša Ana B. -

Strokovno Sreˇcanje in 68. Obˇcni Zbor Dmfa Slovenije

DRUŠTVO MATEMATIKOV, FIZIKOV IN ASTRONOMOV SLOVENIJE STROKOVNO SRECANJEˇ IN 68. OBCNIˇ ZBOR DMFA SLOVENIJE Maribor, 14. in 15. oktober 2016 M. Razpet: Cornus kousa STROKOVNO SRECANJEˇ IN 68. OBCNIˇ ZBOR DMFA SLOVENIJE Maribor, 14. in 15. oktober 2016 Društvo matematikov, fizikov in astronomov Slovenije Oktober 2016 VSEBINA Nagovor predsednika . .7 Predlog dnevnega reda obcnegaˇ zbora . .9 Vspomin...................................................... 10 Akademik Ivan Vidav . 16 Profesor Josip Grasselli . 17 Profesor Janez Strnad . 19 Porocilaˇ organov društva . 20 Poroˇcilopodpredsednice ......................................... 20 Slovenski odbor za fiziko ......................................... 21 Slovenski odbor za matematiko .................................... 22 Slovenski odbor za astronomijo .................................... 24 Raˇcunovodsko poroˇciloza leto 2015 ................................. 25 Porocilaˇ tekmovalnih komisij . 28 52. tekmovanje osnovnošolcev v znanju matematike za Vegova priznanja ........ 28 60. tekmovanje srednješolcev v znanju matematike za Vegova priznanja ......... 29 16. tekmovanje dijakov srednjih tehniških in strokovnih šol v znanju matematike ... 30 16. tekmovanje dijakinj in dijakov srednjih poklicnih šol v znanju matematike ..... 31 14. tekmovanje dijakinj in dijakov v znanju poslovne in finanˇcnematematike ter statistike .............................................. 31 27. državno tekmovanje iz razvedrilne matematike ....................... 32 36. tekmovanje osnovnošolcev iz znanja fizike za Stefanova -

1919–2012 Doktorat Znanosti in Promocije Doktorjev Znanosti Na Univerzi V Ljubljani

Doktorat znanosti in promocije doktorjev znanosti na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1919–2012 1 Na ovitku spredaj: Slovesna promocija doktorjev in doktoric znanosti, promotor rektor prof. dr. Ivan Svetlik, Zbornična dvorana Univerze v Ljubljani, oktober 2013. 2 Doktorat znanosti in promocije doktorjev znanosti na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1919–2012 Univerza v Ljubljani (Zgodovinski arhiv in muzej Univerze) Občasna razstava od decembra 2013 do februarja 2014 Kazalo Ivan Svetlik Predgovor 7 Jože Ciperle Uvod 9 Doktorat in promocije doktorjev v zgodovinskem razvoju univerze 11 Jože Ciperle Doktorat in promocije doktorjev v zgodovinskem razvoju univerze 13 Doktorat znanosti in promocije doktorjev znanosti na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1919–2012 23 Tatjana Dekleva Doktorat znanosti in promocije doktorjev znanosti na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1919–1990 25 Marjana Slobodnik Doktorski študij na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1990–2012 46 Tea Anžur, Tatjana Dekleva Kronološki register doktorjev znanosti promoviranih na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1920–2012 54 Tea Anžur, Tatjana Dekleva Osebno kazalo doktorjev znanosti promoviranih na Univerzi v Ljubljani 1920–2012 92 Jože Ciperle, Tatjana Dekleva Seznam razstavljenega gradiva 126 The Doctor of Science Title and Awarding of Doctorates at the University of Ljubljana 1919 – 1990 133 Tatjana Dekleva The Doctor of Science Title and Awarding of Doctorates at the University of Ljubljana 1919 – 1990 135 Marjana Slobodnik Doctoral study at the University of Ljubljana 1990 – 2012 149 5 Predgovor Ugledne univerze po svetu, ki se ponašajo s častitljivo Dodatna vrednost publikacije je kronološki in abece- tradicijo, se kitijo tudi z doktorskim študijem, s kako- dni register vseh, skoraj 10.000 doktorjev znanosti, vostno doktorsko šolo in njenimi diplomanti. -

Some Interesting and Useful Web Sites

Some Interesting and Useful Web Sites http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/prism.php?id=1 Newton Project on line (texts, mss., letters) http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/prism.php?id=47 Newton’s optical papers https://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/electron/jjinfo.htm# bibliography on the history of the electron http://www.mathpages.com/home/kmath677/kmath677.htm and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poynting’s_theorem http://dbserv.ihep.su/hist/owa/hw.fulltextlist_txt downloads of many primary texts http://www.aip.org/history/web-link.htm on-line exhibitions and links http://alberteinstein.info/ Einstein Archives with on-line database http://myweb.rz.uni-augsburg.de/~eckern/adp/history/Einstein-in-AdP.htm for Einstein’s articles in Annalen der Physik http://press.princeton.edu/books/einstein11/c_biblio.pdf cumulative bibliography of all primary and secondary sources cited in Collected Papers of Albert Einstein vols. 1–10 http://www.pitt.edu/~jdnorton/Goodies/Einstein_stat_1905/ on Einstein’s statistical papers https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RpLOKqTcSk Einstein Bose CondensateColdest Place in the Universe http://www.calcuttaweb.com/people/snbose.shtml on Bose https://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje41/text10 and 11.htm on Natanson http://nobelprize.org/physics/laureates/1927/compton-lecture.html Compton’s biography http://eldorado.tu-dortmund.de/bitstream/2003/24257/1/006.pdf http://www.ifpan.edu.pl/ON-1/Historia/natanson.htm http://edition-open-access.de/studies/2/index.html quantum theory & quantum mechanics textbooks http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1914 (von Laue), resp. .../1915 (the Braggs), /1919 (Stark), /1921 (Einstein), /1922 (Bohr), /1923 (Millikan), /1927 (Compton), /2012 (Haroche), etc.