An Action Learning Module for Local Authorities to Develop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relief Food Distribution in Mali

WORLD VISION ISTEKNATIONAL WORLD VISION RELIEF ORGANIZATION END OF PROJECT REPORT 1985 DROUGHT -RELIEF FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN MALI (T.A. 688-XXX-000-5622) (T.A. 641-XXX-000-5603) (P.A. 899-950-XXX-5784) Report prepared £or The United State Agency for International Development Mali Mission and AIDjW Office of Food for Peace March 1986 TABLE 'OF CONTENTS Page no. I INTRODUCTION 11. SUMMARY OF ACHIEVEMENTS AND CONSTRAINTS 111. TRANSPORT# STORAGE, LOSS AND DAMAGE I IV. DISTRIBUTION IN- THE 7TH REGION A. Project Personnel B. Logistics C. Start Up and Inter-Agency Coordination D. Population Surveys E. Distribution ' P'.. Distribution in Gao Ville G. Menaka Feeding Centers V. DISTRIBUTION IN NIORO A. Project Personnel B. Logistics C. Population Surveys D. Distribution VI. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS VII. SUMMARY TABLES OF DISTRIBUTIONS ANNEX - ACCOUNTINGI CONTROL AND REPORTING FORMS USED BY WV. ' ANNEX I. INTRODUCTION . World Vision International is a Christian humanitarian organiza- tion with the world headquarters in Monrovia, California, and currently active in major relief activities in four African nations using US PL480 food commodities. USAID requested the . World Vision Relief Organization to assist with the international response to the Malian drought in 1985 by distributing 10,000 metric tonnes of grain under a Direct Grant from the AID ~oodfor Peace Office. World Vision was to take full responsibility for transport and management of commodities from transfer of title in Ghana, through distribution in the target areas of Nioro du Sahel (1st Region), Gao, Menaka and Ansongo (7th region), Republic of Mali. The goal ofthe project wastoprevent starvationandstem the massive migration toward urban centers in these areas which had been severely affected by 5 years of inadequate rainfall. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Rapport De L'etude Genre Menee Dans Les Aires De

RAPPORT DE L’ETUDE GENRE MENEE DANS LES AIRES DE SANTE APPUYEE PAR MEDECINS DU MONDE ESPAGNE DANS LE DISTRICT SANITAIRE DE BAFOULABE Draft Projet d’Amélioration de l’Accès aux Soins de Santé Primaires et l’Exercice des Droits Sexuels et Reproductifs, Région de Kayes au Mali-Cercle de Bafoulabe Bamako, 21 octobre 2017 - Moussa TRAORE, consultant principal - Dr Sékou Koné, assistant de recherche - Adiaratou Diakité, socio-anthropologue - Salimata Sissoko, assistante de recherche Projet d’Amélioration de l’Accès aux Soins de Santé Primaire et l’Exercice des Droits Sexuels et Reproductifs, Région de Kayes, Cercle de Bafoulabe Sommaire PAGES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ............................................................................................................................... 3 Sigles et Abréviations .............................................................................................................................. 4 REMERCIEMENTS .................................................................................................................................... 7 I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 8 II. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS ............................................................................................ 9 III. APERÇUE SOCIODEMOGRAPHIQUE ET SANITAIRE ................................................. 10 IV. OBJECTIFS DE L’ETUDE .................................................................................................... -

Admis Def 2018 Ae Nioro

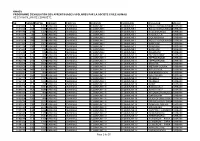

LISTE DES ADMIS AU DEF 2018 - ACADEMIE D'ENSEIGNEMENT DE NIORO N° Place PRENOMS NOM Sexe Année de Naiss Lieu de Naiss. Opon DEF Statut élève Ecole CAP 117 Aliou BOLY M 2003 Fasssoudébé CLASS REG Fassoudébé 2ème C DIEMA 118 Yacouba BOLY M 2002 Fassoudébé CLASS REG Fassoudébé 2ème C DIEMA 189 Mahamadou CAMARA M 2001 Libreville CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 262 Mariam CISSE F 2002 Fassoudébé CLASS REG Fassoudébé 2ème C DIEMA 293 Assa COULIBALY F 2002 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 360 Konsou Fatoumata COULIBALY F 2003 Bamako CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 388 Minata COULIBALY F 2000 M'Pèssoba CLASS CL Béma 2ème C DIEMA 496 Oumou DIA F 2004 Niantanso CLASS REG Fassoudébé 2ème C DIEMA 562 Djibril DIAKITE M 2002 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 842 Ousmane Chérif DIARRA M 2003 Bamako CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 905 Diougoudou DIAWARA M 2002 Libreville CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 910 Douga DIAWARA M 2002 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 965 Yatté DIAWARA M 2000 Grouméra CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1123 Moctar FOFANA M 2003 Touna CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1188 Foussény HAÏDARA M 2002 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1195 Tidiane KAH M 2003 Fassoudébé CLASS REG Fassoudébé 2ème C DIEMA 1198 Issouf KALOGA M 2000 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1202 Abdoulaye KAMISSOKO M 2002 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1205 Dengoumé KAMISSOKO M 2000 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1209 Komakan KAMISSOKO M 2002 Béma CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1211 Madi Tidiane KAMISSOKO M 2004 Bamako CLASS REG Béma 2ème C DIEMA 1241 Mohamed KANTE M 2003 Guédébiné CLASS REG -

Académie D'enseignement De NIORO

MINISTERE DE L'EDUCATION NATIONALE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------------- Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi ------------------- SECRETARIAT GENERAL DECISION N° 20 13- / MEN- SG PORTANT ORIENTATION DES ELEVES TITULAIRES DU D.E.F, SESSION DE JUIN 2013, AU TITRE DE L'ANNEE SCOLAIRE 2013-2014. LE MINISTRE DE L'EDUCATION NATIONALE, Vu la Constitution ; Vu le Décret N°2013-721/P-RM du 8 septembre 2013 portant nomination des membres du Gouvernement ; Vu l'Arrêté N° 09 - 2491 / MEALN-SG du 10 septembre 2009 fixant les critères d’orientation, de transfert, de réorientation et de régularisation des titulaires du Diplôme d’Etudes Fondamentales (DEF) dans les Etablissements d’Enseignement Secondaire Général, Technique et Professionnel ; Vu la Décision N°10-2742/MEALN-SG-CPS du 04 juin 2010 déterminant la composition, les attributions et modalités de travail de la commission nationale et du comité régional d'orientation des élèves titulaires du diplôme d'études fondamentales (DEF), session de juin 2010 ; Vu la décision N°2011-03512 / MEALN–SG-IES du 19 Août 2011 fixant la Liste des Etablissements Privés d'Enseignement Secondaire éligibles pour accueillir des titulaires du Diplôme d'Etudes Fondamentales (DEF) pris en charge par l’Etat ; Vu la décision N° 2011-03614 / MEALN–SG-IES du 07 Septembre 2011 fixant la Liste additive des Etablissements Privés d'Enseignement Secondaire éligibles pour accueillir des titulaires du Diplôme d'Etudes Fondamentales (DEF) pris en charge par l’Etat ; Vu la décision N° 2011-03627 / MEALN–SG-IES du 09 Septembre 2011 fixant -

L'histoire Des Vingt Ans Du Jumelage (1994-2014)

L’HISTOIRE DES VINGT ANS DU JUMELAGE (1994 - 2014) ENTRE MAROLLES-EN-HUREPOIX ET LAKAMANE Racontée par l’association des Amis du Jumelage de Marolles-en-Hurepoix Rédacteur Vincent FAUVELL-CHAMPION Commission Mali des Amis du Jumelage Titre original : L’histoire des vingt ans du jumelage (1994-2014) entre Marolles-en-Hurepoix et Lakamané Racontée par l’association des Amis du Jumelage de Marolles-en-Hurepoix - février 2014 - Droits de la propriété intellectuelle - Copyright : L’association « Les Amis du Jumelage » de Marolles-en-Hurepoix se réserve tous droits de reproduction et d’exploitation conformément à la législation en vigueur. 2 MAROLLES-EN-HUREPOIX Ville jumelée avec 3 Le mot du président de l’association des Amis du Jumelage de Marolles-en-Hurepoix Chères lectrices, chers lecteurs, Quand vous lirez cet opuscule, vous ferez partie d’un voyage dans le temps entre Marolles- en-Hurepoix et la commune rurale de Lakamané au Mali qui débuta officiellement il y a maintenant vingt ans. C’est une très belle histoire qui s’est construite au fil du temps en toute discrétion. Cette première étape des vingt ans que nous célébrons en 2014 n’est certainement pas un achèvement, mais le début d’une relation désormais mature dont nous avons tous le devoir de faire vivre durablement. C'est par conséquent l'histoire d'un jumelage réussi racontée par ceux qui l’ont vécu pour et par les citoyennes et les citoyens de nos deux communes. L'histoire d'une amitié aux visages multiples. Pendant toutes ces années les deux principaux animateurs auront été Madame Dany PUICHAFFRET et surtout Monsieur Louis FRIMBAULT. -

MC Long Report

LAFIA (PEOPLE AT PEACE) Quarterly Report JANUARY 1 – MARCH 31, 2021 Program Information Grantee: Mercy Corps Project Title: People at Peace (Lafia) Grant Number: 720-688-20-CA-00001 Country: Mali Funding Amount: $ 1,684,850.00 Grant Dates: 10/16/2019 – 09/30/2021 Quarter (Dates) being discussed: 01/01/2021 – 03/31/2021 Date Progress Report is submitted: April 30, 2021 Table of Contents ACRONYMS 1 PROGRAM SCOPE OF WORK 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROGRAM ACHIEVEMENTS 4 Contextual Information 4 Progress by Program Objectives 4 MONITORING, EVALUATION & LEARNING 13 CHALLENGES & LESSONS LEARNED 14 Challenges and Lessons Learned 14 Sustainability 14 Environmental Compliance 14 PLANNED ACTIVITIES – NEXT QUARTER 15 Tables & Figures Table 1: Summary of S4C Sessions ................................................................................................................ 5 Table 2: EWER system challenges and recommendations ............................................................................. 9 Table 3: Identified conflict drivers and proposed joint projects ...................................................................... 10 Figure 1: Incidents collected by the Bamako EWER ....................................................................................... 8 ACRONYMS CAFO Coordination of Women's Associations and NGOs in Mali (Coordination des Associations et ONGs Féminines du Mali) CMM Conflict Management and Mitigation CMAS Coordination des mouvements, Associations et Sympathisants de l'Imam Mahmoud Dicko CNJ National Youth Council -

Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report October 1, 2008 – December 31, 2008

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative USAID Mali Mission Awards Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) 12-2008 Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report October 1, 2008 – December 31, 2008 INTSORMIL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilusaidmali INTSORMIL, "Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report October 1, 2008 – December 31, 2008" (2008). USAID Mali Mission Awards. 16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilusaidmali/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USAID Mali Mission Awards by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report October 1, 2008 – December 31, 2008 USAID/EGAT/AG/ATGO/Mali Cooperative Agreement # 688-A-00-007-00043-00 Submitted to the USAID Mission, Mali by Management Entity Sorghum, Millet and Other Grains Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) Leader with Associates Award: EPP-A-00-06-00016-00 INTSORMIL University of Nebraska 113 Biochemistry Hall P.O. Box 830748 Lincoln, NE 68583-0748 USA [email protected] Transfer of Sorghum and Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Introduction This report details the recent progress achieved under the Cooperative Agreement # 688-A-00- 007-00043-00. The report covers progress in the Production-Marketing, Food Processing and Décrue Sorghum components. -

Note Technique SAP Mars 10032015.Pdf

PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ------------***------------ ------------***------------ COMMISSARIAT A LA SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ------------***------------ SYSTEME D’ALERTE PRECOCE (S.A.P) BP. 2660, Bamako-Mali Tel :(223) 20 74 54 39 ; Adresse email : [email protected] Adresse Site Web : www.sapmali.com NOTE TECHNIQUE EVALUATION DEFINITIVE DE LA SITUATION ALIMENTAIRE CAMPAGNE AGROPASTORALE 2014-2015 Mars 2015 Evaluation définitive de la situation alimentaire, campagne agropastorale 2014-2015 Présentation du SAP Le SAP est un système de collecte permanente d’informations sur la situation alimentaire. Sa mission consiste essentiellement à fournir à l’ensemble du système de sécurité alimentaire du pays les informations nécessaires à une affectation optimale du stock national de sécurité dans le cadre d'opérations d'aides alimentaires ciblées ou à une utilisation efficiente des fonds de sécurité alimentaire dans des actions d’atténuation d’insécurité alimentaire. Son objectif est de déterminer suffisamment à l'avance les populations les plus vulnérables risquant de connaître des difficultés alimentaires et/ou nutritionnelles, de dire les raisons du risque, de dire à partir de quand, pour combien de temps, avec quelle intensité et quelles sont les actions d’atténuation possibles. Les informations sont recueillies auprès des services administratifs, techniques, de la société civile et des élus locaux depuis les communes vers les chefs-lieux de cercles, les chefs-lieux de Régions et enfin Bamako. Au niveau de chaque chef-lieu de Région, l'équipe régionale SAP chargée du recueil des informations est appuyée par la Direction Régionale du Plan et de la Statistique. Avant d'être transmises sous forme de rapport mensuel à Bamako, ces informations sont examinées par un Groupe de Travail Régional SAP présidé par le Conseiller aux Affaires Economiques et Financières du Gouverneur de la région. -

Informations Sur Les Élus

Informations sur les élus Année d'élection 2009 La région de Kayes compte 1795 élus dont 121 femmes Le cercle de BAFOULABE compte 215 élus dont 6 femmes La commune de BAFOULABE compte 17 élus dont 1 femmes Fonction NOMS né en SEXE PROFESSION Parti Réélu Maire DOUCOURE Kandé 1952 Masculin Agent de l'administration ADEMA Elu sortant 1er adjoint DIABY Yari 1974 Masculin Commerçant UDD-BDIA Elu sortant 2eme adjoint DEMBELE Demba 1954 Masculin Enseignant URD Elu sortant 3eme adjoint DIARRA Issa 1965 Masculin Agent d'élevage et d'agriculture CODEM Elu sortant Conseiller Communal KEITA Adama Namory 1961 Masculin Agent de l'administration CNID Conseiller Communal DIABY Moussa 1962 Masculin Agriculteur ou éleveur CNID Elu sortant Conseiller Communal SAKILIBA Kama 1969 Feminin CNID Elu sortant Conseiller Communal DIALLO Séga 1966 Masculin Agriculteur ou éleveur CODEM Conseiller Communal DIARRA Djénéba 1965 Masculin Enseignant CNID Conseiller Communal DIALLO Sénabou 1964 Masculin Enseignant ADEMA Conseiller Communal SAKILIBA Moussou Magan 1951 Masculin URD Conseiller Communal DIAKITE Makan 1950 Masculin Agent de santé CNID Elu sortant Conseiller Communal FANE Abdoulaye 1960 Masculin Enseignant ADEMA Conseiller Communal SISSOKO Sidi 1976 Masculin Enseignant ADEMA Conseiller Communal DIABY Mady Assa 1954 Masculin Agent de santé ADEMA Conseiller Communal SIDIBE Balla 1961 Masculin Agriculteur ou éleveur UDD-BDIA Conseiller Communal DIALLO Sada 1961 Masculin Agriculteur ou éleveur CNID Elu sortant mercredi 12 août 2009 repInformationsElus Page 1 sur -

Echantillon 2016.Pdf

OMAES PROGRAMME D'EVALUATION DES APRENTISSAGES SCOLAIRES PAR LA SOCIETE CIVILE AU MALI SE ECHANTILLON DE L'ENQUËTE SE NBMENPOPSE REGION CERCLE ARROND COMMUNE IDVILLAGE MILIEU 9191005 171 1207 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I BOULKASSOUMBOUGOU URBAIN 9191039 203 1388 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I BOULKASSOUMBOUGOU URBAIN 9191070 236 1447 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I DJELIBOUGOU URBAIN 9191109 90 639 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I FADJIGUILA URBAIN 9191145 146 1081 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I DOUMAZANA URBAIN 9191168 284 2036 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I BOULKASSOUMBOUGOU URBAIN 9191199 334 1507 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I BANCONI URBAIN 9191224 200 1329 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I BANCONI URBAIN 9191249 103 725 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I BANCONI URBAIN 9191284 164 836 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE I COMMUNE I SIKORONI URBAIN 9192006 177 939 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II HIPPODROME URBAIN 9192018 121 734 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II HIPPODROME URBAIN 9192035 201 1207 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II HIPPODROME URBAIN 9192048 178 1049 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II MISSIRA URBAIN 9192059 197 1195 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II MEDINA-COURA URBAIN 9192074 140 1203 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II BAGADADJI URBAIN 9192091 183 956 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II BAKARIBOUGOU URBAIN 9192106 284 1658 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II BOUGOUBA URBAIN 9192117 204 1397 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II NIARELA URBAIN 9192130 163 1222 BAMAKO BAMAKO COMMUNE II COMMUNE II NIARELA -

Central Mali

SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security No. 2017/5 December 2017 CENTRAL MALI: VIOLENCE, SUMMARY w Initially, the 2012 crisis LOCAL PERSPECTIVES AND affecting Mali was understood to be primarily focused the DIVERGING NARRATIVES northern regions of the country, as were the previous rebellions errupting at regular aurélien tobie* intervals since independence. However, since 2015, the central region of Mopti has called for I. Introduction attention, as it experienced a dramatic increase in the occurrence of violent acts In 2012, at the start of the crisis in Mali, violence appeared to be limited to targeting security forces, the north of the country, in the Gao, Timbuktu and Kidal regions. Three elected or traditional officials, years later, in 2015, the intensification of violence in the central regions has market places or even schools. increasingly drawn the attention of the Malian authorities and international This change in the geographic observers.1 centre of the violence has led Since the start of the crisis, it has been striking to see how the analyses national and international of decision makers have often underestimated the deterioration of the situ- security actors to re-assess ation in the centre of the country and incorrectly evaluated the capacity of their analysis on the root causes of the conflict affecting Mali. the state to deal effectively with the conflicts developing there.2 While it is Central Mali revealed conflict generally accepted that the Malian political and security crisis can no longer dynamics that do not be limited to the north of Mali, it is imperative to obtain a detailed view of the correspond to the usual grid of national and regional dimensions of the problem developing in the centre, analysis applied to Mali’s 3 and the interaction between these two dimensions of the conflict.