LTURE End PERSONALITY Simon Biesheuvel SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE of RACE RELATIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ALFRED and WINIFRED HOERNLE MEMORIAL LECTURE 1961 LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY-TODAY by D

THE ALFRED AND WINIFRED HOERNLE MEMORIAL LECTURE 1961 LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY-TODAY By D. V. COWEN Professor of Comparative Law, University of Cape Town I Second Impression DELIVERED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE SOUTH AFRICANINSTITUTEOFRACERELATIONSP.O.Box 97 Johannesburg THE ALFRED AND WINIFRED HOERNLF, MEMORIAL LECTURE A LECTURE entitled the Alfred and Winifred Hoernk Memorial Lecture (in memory of the late Professor R. F. Alfred Hoernl6, President of the South African Institute of Race Relations from 1934 to 1943 and of his wife, the late Winifred Hoernle, President of the Institute from 1948 to 1950, and again from 1953 to 1954), is delivered once a year under the auspices of the Institute. An invitation to deliver the lecture is extended each year to some person having special knowledge and experience of racial problems in Africa and elsewhere. It is hoped that the Hoernl Memorial Lecture provides a platform for constructive and helpful contributions to thought and action. While the lecturers are entirely free to express their own views, which may not be those of the Institute as expressed in its formal decisions, it is hoped that lecturers will be guided by the Institute's declaration of policy that "scientific study and research must be allied with the fullest recognition of the human reactions to changing racial situations; that respectful regard must be paid to the traditions and usages of various national, racial and tribal groups which comprise the population; and that due account must be taken of opposing views earnestly held". Previous lecturers have been the Rt. Hon. J. H. -

Transforming Research Methods in the Social Sciences

Transforming Research Methods in the Social Sciences Case Studies from South Africa Transforming Research Methods in the Social Sciences Case Studies from South Africa EDITORS Sumaya Laher, Angelo Fynn and Sherianne Kramer Transforming Research Methods in the Social Sciences Case Studies from South Africa EDITORS Sumaya Laher, Angelo Fynn and Sherianne Kramer Published in South Africa by: Wits University Press 1 Jan Smuts Avenue Johannesburg 2001 www.witspress.co.za Compilation © Editors 2019 Chapters © Individual contributors 2019 Published edition © Wits University Press 2019 Images and figures © Copyright holders First published 2019 http://dx.doi.org.10.18772/22019032750 978-1-77614-275-0 (Paperback) 978-1-77614-355-9 (Web PDF) 978-1-77614-356-6 (EPUB) 978-1-77614-357-3 (Mobi) 978-1-77614-276-7 (Open Access PDF) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, Act 98 of 1978. All images remain the property of the copyright holders. The publishers gratefully acknowledge the publishers, institutions and individuals referenced in captions for the use of images. Every effort has been made to locate the original copyright holders of the images reproduced here; please contact Wits University Press in case of any omissions or errors. This book is freely available through the OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 Creative Commons License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

Mt South African Luu^Cnu Illagcmm ^O. 74 1959 % Scmtlr Iwiu

m t South African luu^cnu illagcmm ^o. 74 1959 % Scmtlr IWiU'an ^Hagazme OS 74 1950 'outh African CONTENTS Page Page Speech Day, 1958 1 Sports Reports-- Headmistress's Report 1 Swimming 30 Extract from Dr. Simon Tennis 32 Biesheuvel's Address ... 7 Lacrosse 34 Vale 9 Hockev 34 Salve 12 A Trip to Kimberley 37 School Benevolencies Visit to a Gold Mine 38 16 The Africana Museum 39 Achievements and Distinctions 14 A Visit to the Oxygen Works 39 School Officers 15 Contributions- Gifts to the School 16 Nursery Rhymes 41 In Memoriam- A Distant Cousin to the 42 Lion Sir Alfred Le Maitre 17 'n Pragtige Konsert 42 Looking Backwards 18 Le Petit Cochon Definitions 43 44 Items from the School Log 20 Mots Crois^s 44 20 Quid Interest? 45 Staff Tu Quoque 45 Foundation Day 21 Maculae nom Mutantur ... Monstrum Horrendum 45 45 The Grandchildren's Party ... 23 Acknowledgments 45 School Activities and Societies Junior School Section 46 Senior Science Club 25 Gifts to Junior School ... 47 Junior Science Club 25 Foundation Day 47 Debating Society 26 Parents' Day 48 Senior Music Circle 26 Girls and Boys 48 Girl Guides 27 News of Friends 49 The Undenominational Home Visit 27 S.A.O.R.A. Officials and Committe e 57 Sunday Evenings 28 S.A.O.R.A. Directory 58 School Tour of Europe 29 Reference to List of Married The SchooJ Play 29 ' Names 91 ic African JWirean JHagazme SPEECH DAY -8th NOVEMBER, 1958 Headmistress's Report Mr. Chairman, Dr. Biesheuvel, Mrs. Biesheuvel, Ladies and Gentlemen, If the welcoming speeches which you have just heard have something of a Hail and Farewell touch about them, I hope you will forgive the spea kers-for this is, I suppose, rather a special occasion. -

Relevance': South African Psychology in Focus

A history of ‘relevance’: South African psychology in focus Wahbie Long Thesis presentedUniversity for the Degree of of Cape Doctor ofTown Philosophy in the Department of Psychology University of Cape Town April 2013 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town University of Cape Town i CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VI ABSTRACT VII NOTE TO EXAMINERS VIII LIST OF ACRONYMS IX CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Becoming a psychologist in South Africa 1 The disputed ‘relevance’ of South African psychology 1 Defining ‘relevance’ 2 Thesis outline 4 CHAPTER 2: A HISTORY OF ‘RELEVANCE’ 7 Chapter overview 7 The worldwide ‘irrelevance’ of higher education 7 The ‘irrelevance’ of American psychology 9 The ‘irrelevance’ of European psychology 11 The ‘irrelevance’ of Third World psychology 12 Indian ‘relevance’ 13 Chinese ‘relevance’ University of Cape Town 14 Filipino ‘relevance’ 15 Latin American ‘relevance’ 17 Islamic ‘relevance’ 18 African ‘relevance’ 19 South African ‘relevance’ 21 Discussion 25 CHAPTER 3: THEORIZING ‘RELEVANCE’ 29 Chapter overview 29 Psychology and its subject matter 29 ii Pure and applied psychology 31 Psychology and social change 32 ‘Relevance’ as rhetoric 33 ‘Relevance’, realism and relativism 34 -

The Face of Africa

The Face of Africa Essays in Honour of Ton Dietz Wouter van Beek, Jos Damen, Dick Foeken (eds.) Occasional Publication 28 513779-L-os-ASC Processed on: 13-9-2017 The Face of Africa Dietz Essays.indd 1 11/09/2017 09:17 513779-L-bw-ASC Processed on: 13-9-2017 PDF page: 1 Dietz Essays.indd 2 11/09/2017 09:17 513779-L-bw-ASC Processed on: 13-9-2017 PDF page: 2 The Face of Africa Essays in Honour of Ton Dietz Wouter van Beek, Jos Damen & Dick Foeken (eds.) Dietz Essays.indd 3 11/09/2017 09:17 513779-L-bw-ASC Processed on: 13-9-2017 PDF page: 3 Authors have made all reasonable efforts to trace the rightsholders to copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful, the publisher welcomes communication from copyright holders, so that the ap- propriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. ASCL Occasional Publication 28 Published by: African Studies Centre Leiden Postbus 9555 2300 RB Leiden [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover photo: Stamps from Zanzibar, Mauretania and the Netherlands Design by Jos Damen and Harro Westra Maps: Nel de Vink (DeVink Mapdesign) Layout: Sjoukje Rienks, Amsterdam Printed by Ipskamp Printing, Enschede ISBN: 978-90-5448-163-8 © Wouter van Beek, Jos Damen and Dick Foeken, 2017 Dietz Essays.indd 4 11/09/2017 09:17 513779-L-bw-ASC Processed on: 13-9-2017 PDF page: 4 Table of Contents Introduction 9 Wouter van Beek, Jos Damen & Dick Foeken PART I Coping with Africa 1 Seasonality of water consumption by the urban poor: The case of Homa Bay, Kenya 25 Dick Foeken & Sam O. -

Race Differences in Intelligence; an Evolutionary Analysis

Table of Contents TITLE PAGE RACE DIFFERENCES IN INTELLIGENCE An Evolutionary Analysis Second, Revised Edition BY RICHARD LYNN WASHINGTON SUMMIT PUBLISHERS / 2015 COPYRIGHT PREFACE To the Second Edition World Distribution of Intelligence Figure 1. World distribution of the intelligence of indigenous people Chapter 1 THE MEANING AND MEASUREMENT OF INTELLIGENCE 1. Definition of Intelligence 2. The Hierarchical Model of Intelligence 3. The IQ 4. Flynn Effects Chapter 2 THE MEANING AND FORMATION OF RACES 1. The Formation of Races, Varieties, and Breeds 2. Varieties in Non-human Species 3. Taxonomies of Races 4. Race Differences in Diseases 5. Do Races Exist? Chapter 3 EUROPEANS 1. Intelligence of Indigenous Europeans 2. Lower Average IQs in Southern Europe 3. Europeans outside Europe 4. European University Students 5. Brain Size 6. The Heritability of Intelligence in Europeans Chapter 4 SUB-SAHARAN AFRICANS 1. Intelligence of Sub-Saharan Africans in Africa 2. High-School and University Students 3. Sub-Saharan Africans in the Caribbean and Latin America 4. Sub-Saharan African-Americans in the United States 5. Sub-Saharan Africans in Britain 6. Sub-Saharan Africans in Canada 7. Sub-Saharan Africans in the Netherlands, France, and Belgium 8. Sub-Saharan Africans in Israel 9. Short-Term Memory and Perceptual Speed Abilities of Sub-Saharan Africans 10. Musical Abilities of Sub-Saharan Africans 11. Reaction Times of Sub-Saharan Africans 12. Brain Size of Sub-Saharan Africans and Europeans 13. Sub-Saharan African-European Hybrids 14. High Intelligence of Sub-Saharan African Infants 15. Heritability of Intelligence in Sub-Saharan African-Americans 16. Validity of Low African IQs 17. -

SAPA, Science and Society: a Debacle Revisited

PINS, 2014, 47, 41 – 58 SAPA, science and society: A debacle revisited Abstract Wahbie Long Little is known about the first national association to be Department of Psychology, established for psychologists in South Africa: the South African University of Cape Town, Psychological Association (SAPA). While it is commonly assumed Rondebosch, that Anglophone psychologists were politically enlightened in Cape Town comparison with their Afrikaner counterparts, this paper attempts [email protected] to illuminate the complexities of SAPA’s intellectual project. Offering a critical discourse analysis of eight presidential and Keywords: opening addresses delivered at national congresses between 1950 apartheid, critical discourse and 1962, the paper identifies among SAPA’s Afrikaner presidents analysis, Psychological a preoccupation with a socially relevant psychology, enunciated Institute of the Republic in the form of a professionalist discourse that encouraged public of South Africa (PIRSA), service yet bore no trace of Christian-National influence. Among South African Psychological English-speaking psychologists, by contrast, social responsiveness Association (SAPA), White was less of a priority in a discourse of disciplinarity concerned English-speaking South with fundamental debates in the field. It is suggested that these African (WESSA) divergent conceptions regarding the role of psychology in society presaged the SAPA split of 1962 and provide, also, an important historical perspective from which to view a contemporary struggle within the discipline. The 1962 splitting of the South African Psychological Association (SAPA) ranks among the most distasteful episodes in the history of psychology in South Africa. While a fair amount has been written on the subsequent founding of the whites-only Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa (PIRSA) – see, for example, Long (2014a, b) – comparatively little is known about SAPA, which was established in 1948 as the first national association for psychologists in the country. -

SAPA, Science and Society: a Debacle Revisited

PINS, 2014, 47, 41 – 58 SAPA, science and society: A debacle revisited Abstract Wahbie Long Little is known about the first national association to be Department of Psychology, established for psychologists in South Africa: the South African University of Cape Town, Psychological Association (SAPA). While it is commonly assumed Rondebosch, that Anglophone psychologists were politically enlightened in Cape Town comparison with their Afrikaner counterparts, this paper attempts [email protected] to illuminate the complexities of SAPA’s intellectual project. Offering a critical discourse analysis of eight presidential and Keywords: opening addresses delivered at national congresses between 1950 apartheid, critical discourse and 1962, the paper identifies among SAPA’s Afrikaner presidents analysis, Psychological a preoccupation with a socially relevant psychology, enunciated Institute of the Republic in the form of a professionalist discourse that encouraged public of South Africa (PIRSA), service yet bore no trace of Christian-National influence. Among South African Psychological English-speaking psychologists, by contrast, social responsiveness Association (SAPA), White was less of a priority in a discourse of disciplinarity concerned English-speaking South with fundamental debates in the field. It is suggested that these African (WESSA) divergent conceptions regarding the role of psychology in society presaged the SAPA split of 1962 and provide, also, an important historical perspective from which to view a contemporary struggle within the discipline. The 1962 splitting of the South African Psychological Association (SAPA) ranks among the most distasteful episodes in the history of psychology in South Africa. While a fair amount has been written on the subsequent founding of the whites-only Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa (PIRSA) – see, for example, Long (2014a, b) – comparatively little is known about SAPA, which was established in 1948 as the first national association for psychologists in the country. -

American Views on South Africa, 1948-1972. Patrick Henry Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1974 American Views on South Africa, 1948-1972. Patrick Henry Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Martin, Patrick Henry, "American Views on South Africa, 1948-1972." (1974). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2622. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2622 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original subm itted. The follow ing explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

A1132-Ba7a-2-002-Jpeg.Pdf

Professor Phillip V. Tobias, B.Sc. Dr. Bertram A. Bradlow, M.B., B.Ch. 1964, B.Sc. Hons., 1947, M.B., B.Ch. 1938, M.D. 1949, who became a Member 1950, Ph. D. 1953, Head of Department of the Royal College of Physicians in of Anatomy at the University, has been Edinburgh in 1953, has been elected a chosen as one of Junior Chamber Fellow of the College. Dr. Bradlow South Africa’s four outstanding young was awarded a fellowship of the men of 1966. American College of Cardiology in 1965. Earlier this year he received the He is also a Member of the Royal Simon Biesheuvel Medal for 1966 for his College of Physicians of London. contribution to the knowledge of man ★ in Africa, in the fields of palaentology, Professor Harold Jenkins, D. Litt. anthropology, genetics and evolution. 1945, has been appointed Regius Profes The medal is awarded by the S.A. Asso sor of Rhetoric and English Literature ciation for the Advancement of Science. at Edinburgh University. Professor Tobias spent several months He was lecturer in English at Wits this year studying ancient man-like from 1936 till 1945 when he returned fossils excavated by Dr. L. S. B. Leakey to the University College, London, as from the Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. He Reader in English. Since 1954 he has received a grant from the National Dr. B. Bradlow. been Professor of English Language and Science Foundation of Washington, D.C. ★ Literature at Westfield College, London. to undertake this research. Dr. K. Somers, M.B., B.Ch. 1949. -

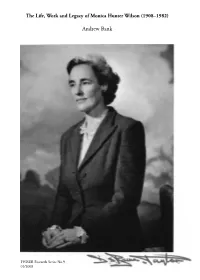

Wilson Booklet.Indd

The Life, Work and Legacy of Monica Hunter Wilson (1908–1982) Andrew Bank FHISER Research Series No.9 01/2008 Published by Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research (FHISER) University of Fort Hare 4 Hill Street East London South Africa 5201 Printed in South Africa by Headline Media ISBN 1 86810 029 6 Design and layout: Jenny Sandler Cover design: Headline Media Copyright: Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means; electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise without prior permission from the publisher. Contents Foreword by Leslie Bank 4 Introduction 6 Childhood: 1 The Hogsback and Alice, 1908–18 8 From History to Anthropology: 2 Girton College, Cambridge, 1927–29 10 A Passion for Fieldwork: 3 Pondoland and the Eastern Cape, 1931–32 14 Reaction to Conquest 1936 16 4 Working with Godfrey among the Nyakyusa: 5 South-western Tanganyika, 1935–38 18 Returning to One’s Roots: 6 Fort Hare, 1944–46 20 Revisiting the Nyakyusa: 7 South-western Tanganyika, 1955 22 African Assistants in the Field: 8 1931-2, 1935-8, 1955 24 Leaving a Legacy: 9 UCT and the Hogsback, 1960–82 26 Endnotes 28 Appendix Monica Hunter Wilson: Awards and Publications 29 4 Foreword The idea of holding a conference to commemorate the life and work of Monica Hunter Wilson was hatched in March 2007 in the rolling hills of Pondoland, where my brother, Andrew Bank, and I had embarked on an exploratory field trip to find Monica Hunter’s original Pondoland field sites. -

S2A3 Marloth Brochure: Centenary Edition 1902

Southern Africa Association for the Advancement of Science Suider-Afrika Genootskap vir die Bevordering van die Wetenskap Rudolf" Marlot:h ' ·Brochure - Bro&jure Centenary Edition 1902 - 2002 Eeufees-uitgawe Dr. H.W. Rudolf Marloth ( 1855 - 1931) Rudolf Marloth was born in Germany and names of several botanical genera and species. immigrated to the Cape of Good Hope in 1883, Rudolf was a founding member of S2A 3 and where he spent the rest of his life. He was an served as its president in 1913-1914. His son, analytical chemist by profession. Though he per Dr. Raimund H. Marloth, was president in formed pioneering research on the biochem 1964-1965. They are the only father and son istry of plants, he was above all a botanist - pair in our list of presidents. one of the greatest ever to have worked in The Rudolf Marloth Brochure was first pub South Africa. He is the author of The Flora of lished in 1989. It is an annual publication SouthAfrica(4 volumes, 1913-1932) and many devoted mainly to the annual award ceremo other publications, and is commemorated in the nies of S2A3. Office-bearers of S2A3 2002 National President Dr. lan Raper National Treasurer Mr. Hermann Ortner National Secretary Mrs. Shirley Korsman COUNCIL MEMBERS Mrs. Esme den Dulk, Dr Frans Korb (on leave of absence) Mr. Eugen Hanau, Mr. Walter Meyer Dr. Glyn Jones, Prof. Cornel is Plug Dr. Freek Kok, Dr. Elise Venter Prof. Michael Wingfield Past Presidents serving on Council Prof P. Smit, Prof Johann Wolfaardt Prof Govert van Drimmelen Vice-Presidents Prof.