Veena Naregal Sudipto Veena Naregal Sudipto 2 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(73) History & Political Science

MT Seat No. 2018 .... .... 1100 MT - SOCIAL SCIENCE (73) History & Political Science - Semi Prelim I - PAPER VI (E) Time : 2 hrs. 30 min MODEL ANSWER PAPER Max. Marks : 60 A.1. (A) Choose the correct option and rewrite the complete answers : (i) Vishnubhat Godase wrote down the accounts of his journey from 1 Maharashtra to Ayodhya and back to Maharashtra. (ii) Harishchandra Sakharam Bhavadekar was also known as Savedada. 1 (iii) Louvre Museum has in its collection the much acclaimed painting of 1 Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. (iv) Indian Hockey team won a gold medal in 1936 at Berlin Olympics 1 under the captaincy of Major Dhyanchand. A.1. (B) Find the incorrect pair in every set and write the correct one. (i) Atyapatya - International running race 1 Atyapatya is Indian outdoor game. (ii) Ekach Pyala - Annasaheb Kirloskar 1 Ekach Pyala is written by Ram Ganesh Gadkari. (iii) Bharatiya Prachin Eitihasik Kosh - Mahadev Shastri Joshi 1 Bharatiya Prachin Eitihasik Kosh - Raghunath Bhaskar Godbole (iv) Gopal Neelkanth Dandekar - Maza Pravas 1 Gopal Neelkanth Dandekar - Hiking tours A.2. (A) Complete the following concept maps. (Any Two) (i) 2 Pune Vadodara Kolhapur Shri Shiv Chhatrapati Kreeda Sankul Vyayam Kashbag Shala Talim Training centres for wrestling Swarnim Kreeda Gujarat Vidyapeeth Sports Hanuman Vyayam Prasarak Mandal Gandhinagar Patiyala Amaravati 2/MT PAPER - VI (ii) 2 (4) Name of the Place Period Contributor/ Artefacts Museum Hanagers (1) The Louvre Paris 18th C Members of the Royal MonaLisa, Museum family and antiquities 3 lakh and eighty brought by Napolean thousand artefacts Bonaparte (2) British London 18th C Sir Hans Sloan and 71 thousand Museum British people from objects British Colonies Total 80 lakh objects (3) National USA 1846CE Smithsonian 12 crore Museum Institution (120 millions) of Natural History (iii) Cultural Tourism 2 Visiting Educational Institutions Get a glimpse of local culture history and traditions Visiting historical monuments at a place Appreciate achievements of local people Participating in local festivals of dance A.2. -

Nieuwsbrief 2018 (PDF)

U ontvangt deze nieuwsbrief als vriend van Kalai Manram, steunstichting van Kattaikkuttu Sangam in India. Van voorzitter Reineke Schoufour Op deze mooie eerste kerstdag willen wij u een fijne tijd wensen met de mensen om u heen. Voor 2019 wensen bestuur en leden van Kalai Manram u veel mooie dingen, dromen die uitkomen en steun als u die nodig heeft! De Nederlandse Stichting Kalai Manram ondersteunt de Kattaikkuttu Sangam in India. Het bestuur heeft hard gewerkt om bekendheid te geven aan dit mooie Kattaikuttutheater en zijn jonge spelers. Ze doet dit door geld te genereren en mee te denken met de oprichters P. Rajagopal en dr. Hanne M. de Bruin. We hopen dat u deze nieuwsbrief met interesse zult lezen en geïnspireerd raakt om op de website te kijken. Natuurlijk hopen wij ook op uw donatie. Wat gebeurde er in 2018 op de Kattaikkuttu Sangam? Examens Alle leerlingen van de 10th, 11th en 12th standard haalden hun examen; ze hebben er hard voor gewerkt, hun opleiding is van hoog niveau maar ze moeten het echt zelf doen! Gefeliciteerd! Karnatic Kattaikkuttu De nieuwste produktie Karnatic Kattaikkuttu was het hoogtepunt van het jaarlijkse theaterfestival van de Kattaikkuttu Sangam dat plaatsvond op 14 augustus 2018. De voorstelling is een unieke samenwerking tussen Karnatic music - klassieke concertmuziek - en Kattaikkuttu theater. Karnatic vocalisten T.M. Krishna en zijn vrouw Sangeetha Sivakumar, Kattaikkuttu acteur P. Rajagopal en dramaturge Hanne M. de Bruin stonden aan de wieg van deze samenwerking en de muzikale en visuele vormgeving. Karnatic Kattaikkuttu werd voor het eerst opgevoerd in Mumbai in december 2017.In Karnatic Kattaikkuttu delen Rajagopal en zijn studenten het toneel met Krishna, Sangeetha en hun musici. -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

Nirvana Ias Academy Current Affairs 1St to 15Th

NIRVANA IAS ACADEMY CURRENT AFFAIRS 1ST TO 15TH FEBRUARY 2019 CONTENT 1. FDI POLICY ON COMMERCE…………………………………………….2 53. SCHEME FOR PENSION & MEDICAL AID TO 2. NATIONAL VIRTUAL LIBRARY…………………………………………..2 ARTISTES…………………………………………………………………..29 3. SHEKATKAR COMMITTEE…………………………………………….....3 54. CHYLP……………………………………………………………………….30 4. NTA STUDENT APP………………………………………………………….3 55. LIGHT HOUSE PROJECT CHALLENGE……………………..…..30 5. DIGITALISATION OF SCHOOLS……………………………………......3 56. MAITHILI LANGUAGE……………………………….………………..31 6. MAHILA COIR YOJAN……………………………………………………….5 57. SCHEDULED TRIBES………………………………….………………..31 7. AGRICULTURE EXPORT POLICY………………………………………..5 58. SPACE TECHNOLOGY IN AGRICULTURE…….………………..32 8. PRE-DEPARTURE ORIENTATION TRAINING 59. ROOF TOP SOLAR POWER SYSTEM…………….………………33 PROGRAMME………………………………………………………………….5 60. 5TH INTERNATIONAL DAM SAFETY CONFERENCE 9. CLEANING PROGRAMME FOR RIVER GANGA…………………..6 2019…………………………………………………………….……………33 10. TOKYO OYLMPICS 2020…………………………………………………..7 61. SEQI……………………………………………………………..……………34 11. 20TH BHARAT RANG MAHOTSAV……………………………………..7 62. SAATH-E…………………………………………………………..……….34 12. KNOW MY INDIA PROGRAMME………………………………………8 63. CLCS-TUS…………………………………………………………………..35 13. EXPORT PROMOTION CAPITAL GOODS SCHEME……………..8 64. E-AUSHADHI PORTAL…………………………………………..…..36 14. ADKL TRANSMISSION SYSTEM…………………………………………9 65. ATOMIC ENERGY BASED POWER……….……………………..36 15. CONSERVATION & PROMOTION OF MEDICINAL 66. BONDED LABOUR………………………………….………………….36 PLANTS………………………………………………………………………….10 67. BHARAT-22 ETF…………………………….….……………….………37 -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Current Affairs November - 2018

MPSC integrated batchES 2018-19 CURRENT AFFAIRS NOVEMBER - 2018 COMPILED BY CHETAN PATIL CURRENT AFFAIRS NOVEMBER – 2018 MPSC INTEGRATED BATCHES 2018-19 INTERNATIONAL, INDIA AND MAHARASHTRA J&K all set for President’s rule: dissolves state assembly • Context: If the state assembly is not dissolved in two months, Jammu and Kashmir may come under President’s rule in January. What’s the issue? • Since J&K has a separate Constitution, Governor’s rule is imposed under Section 92 for six months after an approval by the President. • In case the Assembly is not dissolved within six months, President’s rule under Article 356 is extended to the State. Governor’s rule expires in the State on January 19. Governor’s rule in J&K: • The imposition of governor’s rule in J&K is slightly different than that in otherstates. In other states, the president’s rule is imposed under the Article 356 of Constitution of India. • In J&K, governor’s rule is mentioned under Article 370 section 92 – ‘ Provisions in case of failure of constitutional machinery in the State.’ Article 370 section 92: Provisions in case of failure of constitutional machinery in the State: • If at any time, the Governor is satisfied that a situation has arisen in which the Government of the State cannot be carried on in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution, the Governor may by Proclamation: • Assume to himself all or any of the functions of the Government of the State and all or any of the powers vested in or exercisable by anybody or authority in the State. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

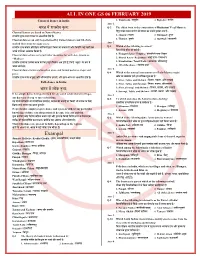

All in One Gs 06 फेब्रुअरी 2019

ALL IN ONE GS 06 FEBRUARY 2019 Classical Dance in India: 3. Yajurveda / यजुर्ेद 4. Rigveda / ऋग्र्ेद Ans- 2 भारत मᴂ शास्त्रीय न配ृ य: Q-2 The oldest form of the composition of Hindustani Vocal Music is: Classical Dances are based on Natya Shastra. सहंदुस्तानी गायन संगीत की रचना का सबसे पुराना 셂प है: शास्त्रीय नृ配य नाट्य शास्त्र पर आधाररत होते हℂ। 1. Ghazal / ग़ज़ल 2. Dhrupad / ध्रुपद Classical dances can only be performed by trained dancers and who have 3. Thumri / ठुमरी 4. Qawwali / कव्र्ाली studied their form for many years. Ans- 2 शास्त्रीय नृ配य के वल प्रशशशित नततशकयⴂ द्वारा शकया जा सकता है और शजन्हⴂने कई वर्षⴂ तक Q-3 Which of the following is correct? अपने 셁पⴂ का अध्ययन शकया है। सन륍न में से कौन सा सही है? Classical dances have very particular meanings for each step, known as 1. Hojagiri dance- Tripura / होजासगरी नृ配य- सिपुरा "Mudras". 2. Bhavai dance- Rajasthan / भर्ई नृ配य- राजस्थान शास्त्रीय नृ配यⴂ के प्र配येक चरण के शलए बहुत शवशेर्ष अर्त होते हℂ, शजन्हᴂ "मुद्रा" के 셂प मᴂ 3. Karakattam- Tamil Nadu / करकटम- तसमलनाडु जाना जाता है। 4. All of the above / उपरोक्त सभी Classical dance forms are based on grace and formal gestures, steps, and Ans- 4 poses. Q-4 Which of the musical instruments is of Indo-Islamic origin? शास्त्रीय नृ配य 셂पⴂ अनुग्रह और औपचाररक इशारⴂ, और हाव-भाव पर आधाररत होते हℂ। कौन सा र्ाद्ययंि इडं ो-इस्लासमक मूल का है? 1. -

UFO Digital Cinema THEATRE COMPANY WEB S.No

UFO Digital Cinema THEATRE COMPANY WEB S.No. THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS CITY ACTIVE DISTRICT STATE SEATING CODE NAME CODE 1 TH1011 Maheshwari 70Mm Cinema Road,4-2-198/2/3, Adilabad 500401 Adilabad Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 698 2649 2 TH1012 Sri Venkataramana 70Mm Sirpur Kagzahnagar, Adilabad - 504296 Kagaznagar Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 878 514 3 TH1013 Mayuri Theatre Mancherial, Adilabad, Mancherial - 504209, AP Mancherial Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 354 1350 4 TH1014 Noor Jahan Picture Palace (Vempalli) Main Road, Vempalli, Pin- 516329, Andhar Pradesh Vempalli Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 635 4055 5 TH1015 Krishna Theatre (Kadiri) Dist. - Ananthapur, Kadiri - 515591 AP Anantapur Y Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 371 3834 Main Road, Gorantla, Dist. - Anantapur, Pin Code - 6 TH1016 Ramakrishna Theatre (Gorantla) Anantapur Y Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 408 3636 515231 A.P 7 TH1017 Sri Varalakshmi Picture Palace Dharmavaram-515671 Ananthapur Distict Dharmavaram Y Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 682 2725 8 TH1018 Padmasree Theatre (Palmaner) M.B.T Road, Palmaner, Chittor. Pin-517408 Chittoor Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 587 3486 9 TH1021 Sri Venkateswara Theatre Chitoor Vellore Road, Chitoor, Dist Chitoor, AP Chittoor Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 584 2451 10 TH1022 Murugan Talkies Kuppam, Dist. - Chittoor, AP Kuppam Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 316 3696 Nagari, Venkateshmudaliyar St., Chittoor, Pin 11 TH1023 Rajeswari Theatre Nagari Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 600 1993 517590 12 TH1024 Sreenivasa Theatre Nagari, Prakasam Road, Chithoor, -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Marathi Theatre in Colonial India the Case of Sangeet Sthanik-Swarajya Athva Municipality

Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 5/2015, S. 287-304 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN: 978-3-86004-316-5 Tools of Satire: Marathi Theatre in Colonial India The Case of Sangeet Sthanik-Swarajya athva Municipality SWARALI PARANJAPE [email protected] Introduction Late nineteenth and early twentieth century colonial India witnessed a remarkable change in its social and political manifestations. After the Great Rebellion of 1857-8, the East India Company, until then domi- nating large parts of the Indian subcontinent, lost its power and the 288 British Crown officially took over power. The collision with the British and their Raj, as the British India was also called by its contem- poraries, not only created mistrust among the people and long-term resistance movements against the impact of foreign rule, it also generated an asymmetrical flow between cultural practices, ideologies, philosophies, art and literatures. This is evident in various Indian languages and Marathi is no exception. Marathi is one of the prominent modern Indian languages and the official language of the State Maharashtra. According to the Census of India 2001, it is the fourth most spoken language in India, after Hindi, Bengali and Punjabi. Traces of satire in Marathi literature can be found in the literary works of Marathi writers as far back as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. By the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, during the colonial era, satire was abundantly used in the literature of Western India. Satire for these Marathi intellectuals – themselves products of the British colonial encounter – was a powerful literary mode to critique the colonial regime and the prevalent social evils of the time. -

Arts-Integrated Learning

ARTS-INTEGRATED LEARNING THE FUTURE OF CREATIVE AND JOYFUL PEDAGOGY The NCF 2005 states, ”Aesthetic sensibility and experience being the prime sites of the growing child’s creativity, we must bring the arts squarely into the domain of the curricular, infusing them in all areas of learning while giving them an identity of their own at relevant stages. If we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness, we need to integrate art education in the formal schooling of our students for helping them to apply art-based enquiry, investigation and exploration, critical thinking and creativity for a deeper understanding of the concepts/topics. This integration broadens the mind of the student and enables her / him to see the multi- disciplinary links between subjects/topics/real life. Art Education will continue to be an integral part of the curriculum, as a co-scholastic area and shall be mandatory for Classes I to X. Please find attached the rich cultural heritage of India and its cultural diversity in a tabular form for reading purpose. The young generation need to be aware of this aspect of our country which will enable them to participate in Heritage Quiz under the aegis of CBSE. TRADITIONAL TRADITIONAL DANCES FAIRS & FESTIVALS ART FORMS STATES & UTS DRESS FOOD (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) Kuchipudi, Burrakatha, Tirupati Veerannatyam, Brahmotsavam, Dhoti and kurta Kalamkari painting, Pootha Remus Andhra Butlabommalu, Lumbini Maha Saree, Langa Nirmal Paintings, Gongura Pradesh Dappu, Tappet Gullu, Shivratri, Makar Voni, petticoat, Cherial Pachadi Lambadi, Banalu, Sankranti, Pongal, Lambadies Dhimsa, Kolattam Ugadi Skullcap, which is decorated with Weaving, carpet War dances of laces and fringes.