Aai- Consumer Welfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENERAL SESSIONS the METAPHYSICS of CONSCIOUSNESS: the What and the How of Cognition (3 Lectures) Harry Binswanger

- ' SECOND I RENAISSANCE CONFERENCES H PRESENTS I ~IDEAS FOR THE RATIONAL MIND Ill" I A PHILOSOPHICAL CONFERENCE I JUNE 28 TO JULY 11, 1998 THE NASHUA MARRIOTT NASHUA, NEW HAMPSHIRE Dear Reader: there is no charge for parking. SECOND RENAISSANCE CONFERENCES is New Hampshire is noted for its tax-free shopping, proud to announce a philosophical conference featur and there are several large shopping malls within a ing new and exciting lectures on epistemology by Dr. ten-minute drive of the hotel. The proximity to his Harry Binswanger. Detailed descriptions of these and toric Boston will allow conferees to attend the city's other lectures, courses, and faculty follow, so let me renowned Independence Day celebrations (with the tell you something about the conference venue. Boston Pops concert and traditional fireworks) and The Nashua Marriott is a first-class hotel situated enjoy the city's many historic, cultural, and culinary in the rolling hills of southern New Hampshire, about attractions. 44 miles northwest of Boston. The scenic White Moun I'm sure you will appreciate the intellectual content tains and New Hampshire's Atlantic coast are both of the conference and enjoy the accommodations of about an hour's drive away. the hotel. Come and experience the joy of meeting The hotel offers numerous amenities, including an people who share your values. I hope you will attend, indoor pool, outdoor sundeck, fitness center, wooded and I look forward to seeing you. jogging trail, and volleyball and basketball courts. In room amenities include hair dryer, iron/ironing board, ~s~ voice-mail, PC dataport, and on-command movies (for a small charge). -

Training the Next Generation

Newsletterof the Ayn Rand@Institute Volume6, Number 4, April 2OO0 Training the Next Generation Since 1995, ARI's undergraduate course on Objectivism: The asked to submit assignments-have included students from Philosophy of Ayn Rand (UPAR) has offered students compre- other disciplines as well as individuals well advanced in their hensive, systematic training in Objectivism-training available careers as lawyers, software engineers, physicists, architects, nowhere else. As the prerequisite course for the Objectivist teachers, businessmen. UPAR helps such individuals develop Graduate Center, UPAR is our means of finding and encour- their ability to think in essentials and to apply philosophy in aging new intellectuals. But UPAR alumni are not the only their own lives and professions. ones to benefit; teaching the course has helped sharpen the UPAR is two academic semestersof 15 weeks each. Stu- skills of the instructors too. dents attend classesby dialing in to ARI's teleconferencing sys- UPAR essentializes the key ideas of Objectlvism, integrates tem, which allows two-way communication between all the those ideas into their broader philosophic context, and con- participants. Thanks to inexpensive long-distance telephone cretizes their real-life personal importance. Students read Dr. rates, students from as far away as Australia and Israel have Peikoff 's Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand, the course been able to attend UPAR. (We are working to develop on-line textbook, and attend weekly lectures that help illumlnate the video courses.) practical, concrete application of philosophy in the students' This year Dr. Harry Binswanger shares the teaching of lives. UPAR with Dr. Onkar Ghate, who will teach the course alone "By emphasizing how the philosophy is lntegrated-week next year. -

“The Experience of Flying”: the Rand Dogma and Its Literary Vehicle Camille Bond Submitted in the Partial Fulfillment Of

“The Experience of Flying”: The Rand Dogma and its Literary Vehicle Camille Bond Submitted in the Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in English April 2017 © 2017 Camille Bond The greatest victory is that which requires no battle. Sun Tzu, The Art of War CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: 2 WHY STUDY RAND? CHAPTER ONE: 8 ON THE FOUNTAINHEAD AND CHARACTER CHAPTER TWO: 39 ON ATLAS SHRUGGED AND PLOT CONCLUSION 70 WORKS CITED 71 Bond 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Bill Cain: Thank you for taking this project under your wing! I could not have asked for a more helpful advisor on what has turned out to be one of the most satisfying journeys of my life. To James Noggle and Jimmy Wallenstein: Thank you for your keen suggestions and advice, which brought new contexts and a clearer direction to this project. To Adam Weiner: Thank you for your assistance, and for the inspiration that How Bad Writing Destroyed the World provided. And to my family: Thank you for your support and encouragement, and for making this project possible. Bond 2 INTRODUCTION: WHY STUDY RAND? Very understandably, I have been asked the question “Why would you study Ayn Rand?” dozens of times since I undertook this project over the summer of 2016. In a decidedly liberal community, Rand’s name alone invokes hostility and disgust; even my past self would have been puzzled to learn that she would go on to spend a year of her life engaging academically with Rand’s work. Many of Rand’s ideas are morally repulsive; it can be physically difficult to read her fiction. -

Nietzsche: the Myth and Its Method Fred Seddon

Reason Papers Articles Nietzsche: The Myth and Its Method Fred Seddon As the number of Objectivist oriented academic philosophers continues to increase, the lenses under which the philosophy will be examined will undoubtedly grow more powerful. Likewise, Objectivist scholarship will become rigorously more intensive; forgoing the entertaining broadside for the well documented and exacting examination. As examples of this development, witness David Kelley's ate Evidence of the Senses and Allan Gotthelf s and James Lennox's anthology Philosophical Issues in Aristotle's Biology, to name but two recent efforts. I wish I could include John Ridpath's article "Nietzsche and Individualism," printed in Vol. 7, ##1 and 2 of the now defunct The Objectivist Forum, as another instance of this trend, but alas, I cannot. The reasons for my reservations constitute the body of this essay. What follows is divided into three parts: (1) a recapitulation of Ridpath's exposition of Nietzsche's philosophy along with a running commentary suggesting alternative interpretations, (2) a short catalogue of Ridpath's errors of scholarship, and (3) a short list of reasons for devoting time to the study of Nietzsche's thought. Exposition Why did Ridpath choose to author an article on Nietzsche? It was, Ridpath tells us, in an effort to ascertain whether Nietzsche is on the side of individualism. The purpose of this article is to examine Nietzsche's philosophy in order to ascertain which side Nietzsche is really on. Based on a study of the complete corpus of Nietzsche's works, this article will present Nietzsche's general philosophical outlook and then use this as the context for understanding his social views, and for judging whether or not he is a defender of individualism. -

The Jefferson School of Philosophy

The Jefferson School of Philosophy. F.conomics. aod Psychology announces a summer conference THE INTELLECTUAL FOUNDATIONS OF A FREE SOCIETY VI to be held at the Clarion Hotel, San Francisco Alrpod, August 1 - 15, 1993 The Jefferson School has been created to advance and dissemin'1e the Jlhilosophical and scientific knowledge that is nec;essary to the existtnce of a flee society. Accordingly, the School's primary mission is the further development, application, and teaching of the 1deu of the pto-:r~ pro-individualist phil,010phers and the pro-freedom, pro-capitalist economists, and of compatible ideu in the field of psychology. ~ of 1t1 activities and programs feature the relevant doctrines of Objectivist and Aristotelian philosophy and of "Austrian" and Classical econorrucs. PRF.SmBNT . ~-- .J ---- VICB--PRESIDE:N'f-----'---~-ooNFERENeE COORDINAreR- George Reisman, Ph.D. Edith Packer, I.D., Ph.D. Diane LeMont, M.A. THE CORE PROGRAM: Thirty-three and a half hours of instruction Leonard Pelkoff, Seven Great Plays a, Philosophy and a, LHerature (seven two-hour Nlllona and one hour-and-a-half INllon devoted entirely to questions and answers) This course is a unique exercise in two skills: philosophic detection and rational esthetic judgment Dr. Peikoff analyus seven great plays from ancient Greece to the 20th Century (works by Sophocles, Shakespeare, Corneille, Schiller, Ibsen, Shaw and-a favorite of Ayn Rand's-Maeterlinck's Morma Vanna). In each case, he sho~s how to discover the essence of the Splot and the motivation of the central characters. He then demonstrates how to identify a play's th~e and deeper abstract meaning. -

FEBRUARY 1994 Obiectivism in Academia

News frorn The Ayn Rand Institure FEBRUARY1994 Upcoming Events: OGC Seeks Applicants.' The Objectivist GraduateCen- Seismic Response: To thosepeople who calledto inquire ter invites applicationsfrom graduatestudents in philosophy about our safety after the earthquakein Los Angeles,we thank or cognatefields, such as.the social sciencesand humanities. you for your concern. With the exception of a few items All coursesare accessiblethroughout the country through an thrown to the floor during the initial quake the Institute suf- audio link-up and videoconferencingmay be in place for the fered no demage. fall semester. For an application form, write to ARI. Ayn Rand in Russian: Medical Panel Rescheduled: "The Clinton Health Care Plan-Malignant or Benign?" a panel discussionin the Los The Book Retums: A Russiantranslation of Wethe Living Angelesarea featuring Dr. George Reismanand Dr. Peter has beenpublished by an entrepreneurin St. Fetersburg,the kPort has been tentatively rescheduledfor early March be- city Ayn Rand left when she moved to the United States. The causeof the earthquake. Proponentsof socialized medicine Januaryrelease heralds the possiblepublication of six addi- will be representedon the panel by a leading hospital adninis- tional titles to be translatedand sold in Russia. Scheduled trator and by a medical advisor to PresidentClinton. The next is The Fountainheadto be followed by Atlns Shrugged. event is sponsoredin part by ARI and by the OccidentalCol- lege premedicalsociety. For further information call Occi- Russian in Amefica: SecondRenaissance Books arurounces dental College (213) 259-2500or Ginger Clark at ARI in late that during the holiday seasonthey sold out of The Morality of February. Individwlism, the Russian-languagetranslation of Ayn Rand's essayspublished by ARI. -

Reply to Critics: Ayn Rand: the Russian Radical - a Work in Progress by Chris Matthew Sciabarra

Reason Papers 25 Reply to Critics: Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical - A Work in Progress by Chris Matthew Sciabarra Nothing quite compares to the exhilaration that an author feels when his work is being noticed. With over two dozen published and electronic reviews, and hundreds of Internet messages debating the value of my book, Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical (Penn State Press, 1995), I now face the challenge of replying to some of my critics more formally, here, in the pages of Reason Papers. I want to thank Tibor Machan for giving me this opportunity. For the purposes of this brief article, however, I will focus only on the broad issues sparked by this debate - on the nature of scholarship, historiography, and social science meth~d.~Those who would like to read more pointed discussions of specific critiques of my work should acquaint themselves with my website: http://pages.nyu.edu/-sciabrrc. My study of Ayn Rand remains a work-in-progress, both in content and in method. My conclusions have been based on an incomplete historical record. Indeed, my historical research continues, and I hope to publish, at a future date, the fascinating results of my ever-deepening investigations into Rand's Russian roots. The provisional nature of the early research, however, does not invalidate my thesis; it merely demonstrates a principle enunciated well by David Gordon (1993), that it is extremely difficult to establish lines of influence in intellectual history. In most cases, he tells us, one cannot provide any more than a suggestive hypothesis; on that basis, "no historical interpretation is apodictically true..." (6-7). -

Chapter 15 Summary and Conclusion by Now, I Think That I Have Brought up to Date My 1968 Book, Is Objecti

Chapter 15 Summary and Conclusion By now, I think that I have brought up to date my 1968 book, Is Objectivism a Religion?, and established with much evidence that objectivism, as well as libertarianism and capitalism, are indeed religions. I have examined the main philosophies of Ayn Rand and her close collaborator, Nathaniel Branden, as well as Alan Greenspan, and have indicated that, until the time of Rand’s death in 1982, their views were fascistic, absolutistic, and fanatically religious. I shall now, in this final chapter, summarize Rand’s main rigidities and show how Rand embodied absolutism in her own life, and encouraged Branden, Greenspan, and thousands of other devout Randians to do the same. Let me say once again that, although I have been a firm atheist and antimystic since the age of 12, I am not completely opposed to religion, nor think that it is without virtue, nor am I fanatically and completely antireligious. I believe that no gods or supernatural entities exist nor will exist. As I have noted for years, if I held such absolutistic views about religion, I would be an inflexible dogmatistas are, of course, many religionists. I figured out a firm but still probabilistic position on religion when I was 12which I call probabilistic atheism. As a probabilistic atheist, I hold that it is highly unlikely that we can ever empirically show (a) that absolutely nothing supernatural exists, nor will exist. But according to the usual laws of probability and the observed nature of humans who live in this world, it appears to be highly probable that no gods, gnomes, fairies, or angels exist and directly or indirectly control human thoughts, feelings, and actions. -

4 Ya__N QR OV Presid V

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax """°"° ""yu`^' Form gg ® Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2009 benefit trust or private foundation ) Department of the Treasury Open to Public have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection Internal Revenue Service ► The organization may A For the 2009 calendar year, or tax year beginning OCT 1 , 2009 and ending S E P 30, 2010 B Check if ply C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable useiFts HE AYN RAND INSTITUTE, THE CENTER FOR Address label or Ochange pdnto HE ADVANCEMENT OF OBJECTIVISM type 22-2570926 O change Doin Business As OIium see Number and street (or P 0 box If mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number OTannin- Specific 50 949-222-6550 eted I ,Cc 121 ALTON PARKWAY Amended tions , Oreturn City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 G Gross receipts $ 13 , 288 467. O=l'c&- IRVINE , CA 92606 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer: DR . YARON BROOK for affiliates? =Yes DU No 2121 ALTON PARKWAY, # 250, IRVINE, CA 9 2 6 0 6 H(b) Are all affiliates included? L Yes 0 No I Tax-exempt status: 0 501 c 3 (insert no.) 0 4947 (a)(1 ) or L-J 527 If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) WWW . AYNRAND . ORG H (c) Grou p exemption number J Website: ► ► K Form of oroanization [ Corporation 0 Trust Association 0 Other ► L Year of formation 19 8 4 M State of legal domicile PA d 1 Briefly describe the organization 's mission or most sign ifi cant activities : TO INCREASE READERSHIP AND UNDERSTANDING^ OF AYN RAND'S WORKS AND TO FIND AND TRAIN THE NEW F 9 1 h r., L. -

L:~. · : · Pa~E·2

. r·~ \ . " • • · ....... 1... .- ; ..... Pa e 1 ' . ._. •'; t Ill • : • ., 'Y • It a, lftt_~,f , "• , , t •~<r.~'J. ·-•~~~,-•Jff ••1 ,, •••, ... ' .,.• ••••, ,r ,_.,,I... l:~... ·, . , ......:.. ·. .. Pa~e·2 ,,.. ,r• • J •ir ~ , ,'f,' • 'to\ .,. ~-.,: .~ . ~ ,/_!;,: ,,, '11,,l ~ ,;. ' , ;; r ~· -. ", ,..::;.r,. 1-. •~,l ·····"' ··,·~·•~~ •.. , -~••::-;r,. ~ ••·;, ,. ..., •,1, .. , d . ..... ... nager •,~ ~-'' , .....,(':""'' •• -., I '►I 1 ,, ·~~ • ...it • .......~ ··t ... ••t \ VI, 1 OPEN LECTURES The tuition for all Open Lectures is included in the basic registration fee. If you are registered for one week, you may_ attend every open lecture through July 23rd, at no additional cliarge. If you are registered Tor two weeks, you may attend every open 1ecture. Your name tag w111 be your admission ticket. All Open Lectures conVffle in the 13allroom. FAch of the four lectures by Dr. Peikoff is from 10:30 am-12:30 pm; all other Open Lectures are from 10:30am-12 pm. Announaments will be made fiveminutes1Jefore the lectures begin at 10:25 am. READING AND WRITING Leonard Peikoff Tiris mini-course offers an Objectivist version of two of the three "R"s. It discusses how to read fiction (specifically, how to analy~~ great plays)-and how to write non-fiction (specifically, how to present great ideas). ~e wnting segment (sessions one and three) focuses on achieving clarity in ideological speeches, letters to the ed!tor, etc. F~r most topics (e.g., establishing context, selecting essentials, creating a structure), students will be assigned_ a bnef paragraph to write in class. Dr. Peikoff's own answer to the assignment (photocopied in advance) will~ handed out as part of the ensuing analysis. 1be rea~hng segm~nt (sessions two and four) focuses on the method of identifying the essential events and the metaphysical value-JUdgments of two twentieth-century Romantic dramas, one now virtually unknown, the other famo~s. -

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository An analysis of the randian political scientific concepts. Merkel, Thomas Allen 1983 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE RANDIAN POLITICAL SCIENTIFIC CONCEPTS By Thomas Allen Merkel A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Government Lehigh University 1983 ProQuest Number: EP76195 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest EP76195 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 This thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. 7?/-v-, /r, fit3 Date Profess or in Charts Chairman of Department -11- "TABLE OF CONTENTS" Certificate of approval ii "AN ABSTRACT OF AN ANALYSIS OF THE RANDIAN POLITICAL SCIENTIFIC CONCEPTS"... 1 Main text 3 PART A: "A BIOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE RANDIAN POLITICAL SCIENTIFIC CONCEPTS .3 Section I: "How Ayn Rand Left the 'Ugliest Country'" 3 Section II: "How She Judged the Americans" 6 PART B: "A TERMINOLOGICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE SUBJECTS".. -

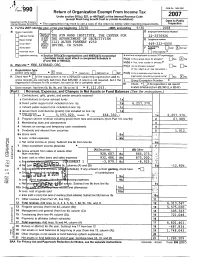

Con Return of Organization Exempt from Income

9i'/• T1 OMB No 1545 0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(aXl) of the Internal Revenue Code 1 2007 black (except lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasu ry Inspection Internal Revenue Service(77) ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting rec A Foethe 2007 calendar y ear, or tax year be g innin g 10/01 , 2007 , and end 9/30 2008 B Check if applicable C D Employer Identification Number Address change IRSIabele THE AYN RAND INSTITUTE, THE CENTER FOR 22-2570926 or print Name change or type THE ADVANCEMENT OF OBJECTIVISM E Telephone number see 2121 ALTON PARKWAY #250 Initial return specific 949-222-6550 Instruc- IRVINE, CA 92606 F metodting Termination tions Acchun • Cash X Accrual Amended return Other (specify) Application pending • Section 501 (cX3) organizations and 4947(aXl ) nonexempt H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations charitable trusts must attach a completed Schedule A H (a) Is this a group return for affiliates' Yes No (Form 990 or 990 - EZ). H (b) If 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates i" G Web site: 0' WWW. AYNRAND. ORG H (c) Are all affiliates included? Yes No (if No,' attach list instructions J Organization type a See ) (check only one Fx] 3 -4 (insert no) 4947(a)(1) or 527 H (d) Is this a separate return filed by an K Check here 0' [j if the organization is not a 509(a)(3) supporting organization and its organization covered by a group rulings Yes X No gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 A return is not required, but if the I Grou p Exem ption Number organization chooses to file a return, be sure to file a complete return M Check ► If the organization is not required L Gross recei pts Add lines 6b, 8b, 9b, and 10b to line 12 - 8,121 , 053.