Three Foundations and the Pittsburgh Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Briefing Papers

The original documents are located in Box C45, folder “Presidential Handwriting, 7/29/1976” of the Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box C45 of The Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library '.rHE PRESIDENT HAS SEEN ••-,.,.... THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON MEETING WITH PENNSYLVANIA DELEGATION Thursday, July 29, 1976 5:30 PM (30 minutes} The East Room ~f\ From: Jim Field :\ ./ I. PURPOSE To meet informally with the Pennsylvania delegates and the State Congressional delegation. II. BACKGROUND, PARTICIPANTS AND PRESS PLAN A. Background: At the request of Rog Morton and Jim Baker you have agreed to host a reception for the Pennsylvania delegation. B. Participants: See attached notebook. C. Press Plan: White House Photo Only. Staff President Ford Committee Staff Dick Cheney Rog Morton Jim Field Jim Baker Dick Mastrangelo Charles Greenleaf • MEMORANDUM FOR: H. James Field, Jr. FROM: Dick Mastrangelo SUBJECT: Pennsylvania Delegation DATE: July 28, 1976 Since Reagan's suprise announcement that he has asked Senator Schweiker to run for Vice President should the convention ever nominate them as a t•am we have been reviewing the entire Pennsylvania situation in order to give the President the most complete and up-to-datebriefing possible for his meeting with the Delegation on Thursday, July 29. -

16 the Determination to Make a Difference

UPMC CancerCenter, partner with University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute VOL 10, NO. 1, 2016 NO. 10, VOL INSIDE 12 Making Medicine Personal | 16 The Determination to Make a Difference | 20 Young Mom Determined to Fight Cancer The University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, working in conjunction with UPMC CancerCenter, UPMC’s clinical care delivery network, is western Pennsylvania’s only National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, reflecting the highest level of recognition by the NCI. 4 12 16 20 UPMC CancerCenter and UPCI Executive Leadership . .2 Heroic Leadership . 3 A message from our Director and Chairman 30 YEARS OF INNOVATION . .4 How Hillman Cancer Center is Changing the Way Health Care is Delivered . .10 MAKING MEDICINE PERSONAL . 12 THE DETERMINATION TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE . 16 Celebrating Elsie Hillman and Her Legacy of Hope . .18 YOUNG MOM DETERMINED TO FIGHT CANCER AND HELP OTHERS ALONG THE WAY . 20. A FUTURE WITHOUT CANCER . 23 2015 Hillman Cancer Center Gala 2015 DONORS . 24 Community Events . 31 News Briefs . 32 Cancer Discovery & Care is a publication of UPMC CancerCenter and the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) and is produced by UPMC Clinical Marketing. © Copyright 2016 UPMC. All rights reserved. No portion of this magazine may be reproduced without written permission. Send suggestions, comments, or address changes to Jessica Weidensall at UPCI/UPMC CancerCenter, Office of Communications, UPMC Cancer Pavilion, 5150 Centre Ave., Suite 1B, Pittsburgh, PA 15232, or via email at [email protected]. University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute | 1 UPMC CancerCenter and University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) Executive Leadership HEROIC LEADERSHIP Nancy E. -

23-05-HR Haldeman

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 23 5 10/1/1971Campaign Other Document Overview of various elections in West Virginia. 1 pg. 23 5 9/30/1971Campaign Other Document Overview of various elections in Delaware. 1 pg. 23 5Campaign Other Document Overview of various elections in Montana. 1 pg. 23 5 9/27/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Strachan to Haldeman RE: an attached document from McWhorter dealing with the National Governors' Conference. 1 pg. Tuesday, June 21, 2011 Page 1 of 7 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 23 5 9/23/1971Domestic Policy Report From McWhorter to Haldeman RE: the 1971 National Governors' Conference and the success of Republican governors at that event. 2 pgs. 23 5 7/15/1971Campaign Memo From A.J. Miller, Jr. to Ed DeBolt RE: political races in Texas in 1971 and 1972. 2 pgs. 23 5 6/25/1971Campaign Memo From Mike Scanlon to DeBolt RE: 1972 campaigns and the Republican Party of Georgia. 1 pg. 23 5 8/3/1971White House Staff Memo From Dent to Haldeman RE: attached reports. 1 pg. 23 5 7/20/1971Campaign Memo From DeBolt to Dent RE: attached political reports on Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wisconsin. 1 pg. Tuesday, June 21, 2011 Page 2 of 7 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 23 5 7/12/1971Campaign Memo From Miller to DeBolt RE: the political state of Missouri in 1971 and the prospects of putting Republicans in office in 1972. -

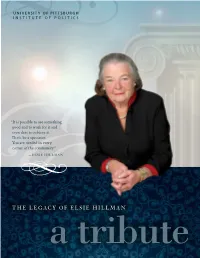

The Legacy of Elsie Hillman

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH INSTITUTE OF POLITICS “It is possible to see something good and to work for it and even dare to achieve it. Don't be a spectator. You are needed in every corner of the community.” —ELSIE HILLMAN THE LEGACY OF ELSIE HILLMAN a tribute It is with great sadness that the Institute of Politics notes the THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE passing of one of Pittsburgh’s finest, Elsie Hilliard Hillman, ELSIE HILLMAN CASE STUDY on August 4, 2015. Because of Elsie’s numerous connections to the Institute, and because of the legacy she is leaving for our n 2009, after some persuasion, Elsie finally agreed to the case study. In crafting the region, we at the Institute would like to take this opportunity to publication, titled Never a Spectator: The Political Life of Elsie Hillman, the Institute share how our relationship with Elsie developed and what she has I and author, Kathy McCauley, conducted dozens of interviews with Hillman’s longtime meant and continues to mean to us personally and in terms of our friends and colleagues and were able to rely on Elsie’s extensive archives, composed of letters, photographs, newspaper clippings, and other mementos from her just-as-extensive career in work going forward. the Republican Party and as a member of the Pittsburgh philanthropic community. Following the completion of the case study, Hillman graciously entrusted the care of her papers to the University of Pittsburgh Library System Archives Service Center, where students, faculty, A SHARED VISION and other researchers can learn lessons in leadership from her political, philanthropic, and humanitarian deeds. -

ARLEN SPECTER /Or Pennsylvania

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu August 21, 1992 MEMORANDUM TO THE LEADER FROM: JOHN DIAMANTAKIOU q,(9 SUBJECT: POLITICAL BRIEFINGS Below is an outline of your briefing materials for the Specter, Nickles, Huckabee and DeWine events. Enclosed are the following briefings for your perusal: 1. Campaign briefing: • overview of race • biographical materials • bills introduced (Nickles, Specter) 2. National Republican Senatorial Briefing National Republican Congressional Committee Briefings on competitive congressional races (OH, OK, AR) 4. Redistricting map ~ Republican National Committee Briefing (OH, OK, AR) 6. State Statistical Summary 7. State Committee/DFP supporter contact list 8. Clips (courtesy of the campaigns) Thank you. Page 1 of 24 16:37 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas 14] 002 08 / 12/ 92 http://dolearchives.ku.edu ARLEN SPECTER /Or Pennsylvania - Citizens for Arlen Specter Hono.-ary Chainnen The Curtis Center, Suite 126 Hon. Hugh Scott 6th and Walnut Streets Hon. William Scranton Philadelphia, PA 19106 Phone: (215) 574-1992 Fax: (215) 574-0784 TO: Office of senator Robert Dole FROM: Carey Lackman, Finance Director Citizens for Arlen specter · RE: WICHITA LUNCHEON FRIDAY, AUGUST 21, 1992 DATE: Wednesday, August 12, 1992 -------------------------~------------~-~------------------------ EVENT DETAILS Event: Fundraising luncheon for senator Arlen Specter Date: Friday, August 21, 1992 Time: 11:30 pm - 1 pm Location: Wichita Club (316/263-5271) 1800 Kansas State Bank and Trust Building 125 North Market street (WEST ROOM) Host: Robert 11 Bob 11 Gelman Kansas Truck Equipment 1521 south Tyler Wichita, KS 67209 o) 316/722-4291 Invitation: a) Letter from Bob Gelman to Gelman List b) Letter from Senator Dole to Dole List Program: Senator Dole Brief Remarks and Q&A (Senator Dole departure early as necessary) senator Specter Brief Remarks and Q&A OVERVIEW CAMPAIGN/PENNSYLVANIA General Election: Senator specter vs. -

Issue 3, 2015

THE HEINZ ENDOWMENTS NONPROFIT ORG Howard Heinz Endowment US POSTAGE Vira I. Heinz Endowment PAID 625 Liberty Avenue PITTSBURGH PA 30th Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15222-3115 PERMIT NO 57 412.281.5777 www.heinz.org facebook.com/theheinzendowments @heinzendow theheinzendowments THE MAGAZINE OF THE HEINZ ENDOWMENTS Issue 3 2015 BACH AND ROLL | PAGE 16 This magazine was printed on Opus Dull, which has among the highest post-consumer waste content of any premium coated paper. Opus is third-party certifi ed according to the chain-of-custody standards of FSC® The electricity used to make it comes from Green e-certifi ed renewable energy. THE AIR WE BREATHE: FOUR PHOTOGRAPHERS PROVIDE AN INTIMATE LOOK AT THE IMPACT OF AIR POLLUTION ON FAMILIES AND INDIVIDUALS IN THE PITTSBURGH REGION — AND THE SCENES ARE TROUBLING. 66793_CVRc2.indd793_CVRc2.indd 1 112/8/152/8/15 77:17:17 PPMM ISSUE 3 2015 (BIG) PLANS mong the indicators of the p4 Pittsburgh initiative’s infl uence on the city is the INSIDE decision by the Penguins hockey team and Adeveloper McCormack Baron Salazar to hire the Copenhagen architectural fi rm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) to design housing and public spaces that will be built at the 28-acre site of the former Civic Arena. Kai-Uwe Bergmann, a partner in BIG (which has offi ces in Copenhagen and New York), participated in the p4 Pittsburgh conference—Planet, People, Place FEATURE: and Performance—which was co-hosted by the City of Pittsburgh, Mayor William Peduto and The Heinz WE SAY NO MORE Endowments, and that launched the initiative focused 8 on innovative and sustainable urban revitalization. -

President, Office of The: Presidential Briefing Papers: Records, 1981-1989 Folder Title: 04/06/1983 (Case File: 135506) (2) Box: 28

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: President, Office of the: Presidential Briefing Papers: Records, 1981-1989 Folder Title: 04/06/1983 (Case File: 135506) (2) Box: 28 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ 2 BACKGIDUND PROVIDED BY USTR STEEL Pace of Domestic Recovery The steel industry is slowly recovering from its long and deep slump, which dates to 1980. The operating rate has risen in recent weeks to 57-58 percent, above last year's 48.4 percent but still well below breakeven. Order books remain weak, and many in the industry believe that demand is going to plateau at about the current level for most of the remainder of 1983. If this happens1 steel unemployment will remain above 100,000 and financial losses will continue. The industry lost $3.3 billion last year, a record, and sees little hope of breaking into the black before next year. In the meantime, necessary investment has had to be postponed. The industry, which estimates that it must invest $6-7 billion a year to modernize, will spend only $1.5 billion this year on plant and equipment. If the pace of modernization does not accelerate, substantial plant closures and company failures are likely. Off Between and Investment Cash-poor and starved for sources of capital, u.s. -

The Legacy of Elsie Hillman

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH INSTITUTE OF POLITICS “It is possible to see something good and to work for it and even dare to achieve it. Don't be a spectator. You are needed in every corner of the community.” —ELSIE HILLMAN THE LEGACY OF ELSIE HILLMAN a tribute It is with great sadness that the Institute of Politics notes the THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE passing of one of Pittsburgh’s finest, Elsie Hilliard Hillman, ELSIE HILLMAN CASE STUDY on August 4, 2015. Because of Elsie’s numerous connections to the Institute, and because of the legacy she is leaving for our n 2009, after some persuasion, Elsie finally agreed to the case study. In crafting the region, we at the Institute would like to take this opportunity to publication, titled Never a Spectator: The Political Life of Elsie Hillman, the Institute share how our relationship with Elsie developed and what she has I and author, Kathy McCauley, conducted dozens of interviews with Hillman’s longtime meant and continues to mean to us personally and in terms of our friends and colleagues and were able to rely on Elsie’s extensive archives, composed of letters, photographs, newspaper clippings, and other mementos from her just-as-extensive career in work going forward. the Republican Party and as a member of the Pittsburgh philanthropic community. Following the completion of the case study, Hillman graciously entrusted the care of her papers to the University of Pittsburgh Library System Archives Service Center, where students, faculty, A SHARED VISION and other researchers can learn lessons in leadership from her political, philanthropic, and humanitarian deeds. -

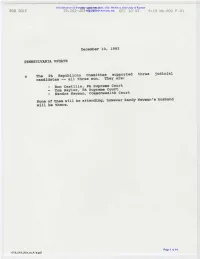

C019 083 009 All.Pdf

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas BOB DOLE 202http://dolearchives.ku.edu 408 5117 ID: 202-408-511 7 DEC 10'93 9 : 19 No . 002 P . 01 December 10, 1993 PENNSYLVANIA UPDATE o The PA Republican Committee supported three j udioial candidates -- all three won. They are: Ron Castille, PA Supreme Court Tom Saylor, PA supreme court Sandra Newman , Commonwealth court None of them will be attending, however Sandy Newman's husband will be there. Page 1 of 84 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu TO: Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Pennsylvania GOP Commonwealth Club Friday, December 10 *Every year, a group of Pennsylvania business and civic leaders travel to New York City for a dinner honoring an outstanding Pennsylvanian. (This year's honoree is Roger Penske, an automobile racing executive. Past honorees include Dick Thornburgh and Teresa Heinz) *Over the past few years, the Pennsylvania GOP has used part of the trip as a fundraiser, and hosted a lunch for Republicans who will be attending the evening's event. *Approximately 150 attendees are expected. *Enclosed talking points include a new anecdote which Senator Hatfield gave me. Page 2 of 84 BOB DOLE This documentID:202-408-5117 is from the collections at the Dole Archives,DEC University 10'93 of Kansas 9:15 No.001 P.02 http://dolearchives.ku.edu f\tt endcmt:~ StPph~n Aichele Dr. Syed R Al i- Zaidi " Anne Anstille ,.. ,,L' ,, .C (?°' ~ 8ob Asher ..........._ Ser: . -

President Ford Committee Weekly Report #21, December 9, 1975

Document scanned from Box 14 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Presidel1t Ford Committee 1828 L STREET, N.W., SUITE 250, WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 (202) 457-6400 WEEKLY REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL CAMPAIGN ORGANIZATION STATE CAMPAIGN ORGANIZATION Colorado Connecticut Hawaii Missouri Minnesota Alaska Arizona Georgia Illinois Iowa Montana New Hampshire New Mexico Oklahoma Oregon Tennessee Washington ISSUES LEGAL TREASURER'S REPORT FINANCE COMMITTEE MISCELLANEOUS PRESS BRIEFING NATIONAL LEAGUE OF CITIES CONVENTION SCHEDULE - WEEK OF DECEMBER 8 The President Ford Committee, Howard H. Callaway, Chairman. David Packard, National Finance Chairman, Robert C. Moot, Treasurer. A copy 0/ our Report /$ filed with the Federal Ekctlon Commls$/on and Is available /0' purchase /rom the Federal Election Comm/$slon, Washinlton, D.C. 20463. President Ford Committee 1828 L STREET. N.W .• SUITE 250. WASHINGTON. D.C. 20036 (202) 457-6400 December 9, 1975 MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT ~ FROM: BO CALLAWAY (;J'0 SUBJECT: Weekly Report #21, Week Ending December 5, 1975 GENERAL CAMPAIGN ORGANIZATION The second edition of The Inside News was mailed to 20,000 Republican households throughout ~country. Fred Slight, Research Coordinator, prepared a fact sheet high lighting your accomplishments as President for use by State PFC leadership. Additional information will be provided in the coming weeks to keep all PFC offices up to date and informed on Adminis tration policy and action. Copies of The Inside News and the Fact Sheet are attached at Tab A. STATE CAMPAIGN ORGANIZATIONS The appointment of Chairmen in Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Missouri and Minnesota bring to 37 the number of state organizations established. -

Forging Our Future Together: Addressing Rural and Urban Needs to Build a Stronger Region

D ECTE OFFIC EL IA L LS A R U E N T N R A d E r A 3 FORGING T 2 OUR FUTURE TOGETHER: ADDRESSING RURAL AND URBAN S NEEDS TO BUILD E B P A STRONGER U T L E REGION C M Y B T E I R S R 19 VE /2 NI 0, 2019 | U Hosted by the University of Pittsburgh Office of the Chancellor and the Institute of Politics UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH OFFICE OF THE CHANCELLOR and INSTITUTE OF POLITICS welcome you to the TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL ELECTED OFFICIALS RETREAT Forging Our Future Together: Addressing Rural and Urban Needs to Build a Stronger Region September 19-20, 2019 University Club If you have questions about the materials or any aspect of the program, please inquire at the registration desk. Contents About the Institute ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Director’s Note .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Retreat Agenda ............................................................................................................................................. 7 2019 Coleman Award Winner – Frederick W. Thieman ............................................................................. 10 Speaker and Panelist Biographies ............................................................................................................... 11 IOP Program Criteria and Strategies .......................................................................................................... -

Elsie Hillman

Never a Spectator The Political Life of Elsie Hillman Kathy McCauley “ It is possible to see something good and to work for it and even dare to achieve it. Don't be a spectator. You are needed in every corner of the community.” —ELSIE HILLMAN AP PHOTO Elsie Hillman (second woman from left) greets presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952. Never a Spectator The Political Life of Elsie Hillman By Kathy McCauley Foreword by Terry Miller DIRECTOR, INSTITUTE OF POLITICS University of Pittsburgh PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ........................................................................................1 1. Introduction .................................................................................9 2. A Modern Republican ............................................................11 The party she joined ......................................................................11 Early influences .............................................................................14 The influence of Hugh Scott..........................................................17 Moving from volunteer to activist ................................................18 Building a network in the Black community ...............................20 Conservatives vs. moderates at the 1964 convention .................22 Ascending the ladder .....................................................................25 Learning as she led .......................................................................27 Friend of labor ...............................................................................30